Representative Works for Solo Viola by Bolivian Composers Mauricio Fredy Cespedes Rivero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamental Techniques in Viola Spaces of Garth Knox. (2016) Directed by Dr

ÉRTZ, SIMON ISTVÁN, D.M.A. Beyond Extended Techniques: Fundamental Techniques in Viola Spaces of Garth Knox. (2016) Directed by Dr. Scott Rawls. 49 pp. Viola Spaces are often seen as interesting extra projects rather than valuable pedagogical tool that can be used to fill where other material falls short. These works can fill various gaps in the violist’s literature, both as pedagogical and performance works. Each of these works makes a valuable addition to the violist’s contemporary performance repertoire as a short, imaginative, and musically satisfying work and can be performed either individually or as part of a smaller set in a larger program (see Appendix A). They all also present interesting technical challenges that explore what are seen as extended techniques but can also be traced back to work on some of the fundamentals of viola technique. Etudes for viola are often limited to violin transcriptions mostly written in the eighteenth, nineteenth, or early twentieth centuries. Contemporary etudes written specifically for viola are valuable but are usually not as comprehensive or as suitable for performance etudes as are Viola Spaces. Few performance etudes cover the technical varieties that are presented in these works of Garth Knox. In this paper I will discuss the historical background of the viola and etudes written for viola. Many viola etudes written in the earlier history of the viola have not continued to be published; this study will also look at why some survived and others are no longer used. Compared to literature for the violin there are large gaps in the violists’ repertoire that Viola Spaces does much to fill; furthermore many violinists have asked for transcriptions of these works. -

Dmitri Shostakovich's Viola Sonata

CG1009 Degree Project, Bachelor, Classical Music, 15 credits 2020 Degree of bachelor in music Department of classical music Handledare: Peter Berlind Carlson Examinator: David Thyrén Arttu Nummela Dmitri Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata History and analysis Abstract In this thesis I’m writing about Dmitri Shostakovich’s only Viola Sonata. I’ve read about Shostakovich life and analysed the sonata. Shostakovich’s Sonata is one of the first pieces from the composer that I have listened to and gotten familiar with. It’s one of the most played viola sonatas and a one of a kind in Russian modern music. The purpose is to dig deep into the music and to understand it. Questions like “why am I playing this like this?” or “how should I do this?” regarding the interpretation of the music is the core of this study. The research is also trying to be of help to get an image of viola music overall and what is the place of Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata in this world. How the piece was reacting to the world around it and how it was affected by the history of viola music and what is its position in the future. Keywords: Dmitri Shostakovich, viola sonata, viola, music history ii iii Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Aim ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Method ...................................................................................................................... -

Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II Elena Artamonova

Feature Article Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II Elena Artamonova Forty-two years after Vadim Borisovsky’s death, the rubato balanced with an immaculate sense for rhythm, recent re-publication of some of his arrangements were never at the expense of the coherence of music he and recordings has generated further interest in the performed, regardless of its period, as his recordings violist. The appeal of his works attests to the depth eloquently attest. and significance of his legacy for violists in the twenty- first century. The first part of this article focused on The discography of Borisovsky as a member of the previously unknown but important biographical facts Beethoven String Quartet is far more extensive, with about Borisovsky’s formation and establishment as a more than 150 works on audio recordings. It comprises viola soloist and his extensive poetic legacy that have music by Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Ravel, only recently come to light. The second part of this Chausson, Berg, Hindemith, and other composers article provides an analysis of Borisovsky’s style of playing of the twentieth century, with a strong emphasis on based on his recordings, concert collaborations, and Russian heritage from Glinka and Rachmaninov to transcription choices and reveals Borisovsky’s special Miaskovsky, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich. This repertoire approach to the enhancement and enrichment of the was undoubtedly influential for Borisovsky in his own viola’s instrumental and timbral possibilities in his selection of transcription choices for the viola. performing editions, in which he closely followed the historical and stylistic background of the composers’ Performing Collaborations manuscripts. -

Sonata for Viola and Piano Op

The American Viola Society Sonata for viola and piano op. 78 Frederick Block (1899-1945) AVS Publications 047 Preface Frederick Block (1899–1945) studied piano and composition in his native Vienna during his youth. After serving on the Italian Front during World War I, he furthered his composition training with Josef Bohuslav Foerster at the New Vienna Conservatory and with Hans Gál at the University of Vienna. Block left Austria after the Nazi invasion in 1938, first settling in London and then immigrating to New York in 1940. While Block composed in a variety of genres, including opera, chamber music, and commercial media (film and radio), he is perhaps best remembered for his early attempt at completing Mahler’s Tenth Symphony, producing a four-hand piano version of movements II, IV, and V.1 The Sonata for Viola and Piano, op. 78 is Block’s final work, completed late in January 1945, less than six months before his death on June 1. The work was performed by Raymond Sabinsky (viola) and Sina Berlynn (piano) on a November 12, 1949, radio broadcast under the auspices of the Frederick Block Committee, an organization founded after the composer’s death to promote his works. Notes about the Sources This edition is based on the manuscript piano score and the manuscript viola part housed in the Frederick Block Papers, JPB 06-21, Music Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Those sources include fingerings and other markings in pencil (in unknown hands), possibly added by later performers. Nonetheless, all fingerings have been incorporated into this edition, and editorial metronome markings have been added to approximate timings written in pencil at the end of each movement in the viola part (movement I: 6 minutes; movement II: 4 minutes; movement III: 4 minutes). -

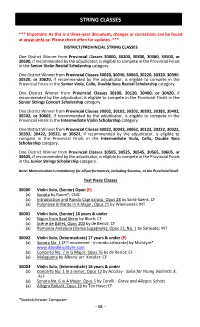

STRING CLASSES STRING CLASSES *** Important: As This Is a Three-Year Document, Changes Or Corrections Can Be Found At

STRING CLASSES STRING CLASSES *** Important: As this is a three-year document, changes or corrections can be found at www.smfa.ca. Please check often for updates. *** DISTRICT/PROVINCIAL STRING CLASSES One District Winner from Provincial Classes 30000, 30200, 30300, 30380, 30500, or 30600, if recommended by the adjudicator, is eligible to compete in the Provincial Finals in the Senior Violin Recital Scholarship category. One District Winner from Provincial Classes 30020, 30040, 30060, 30220, 30320. 30390. 30520, or 30620, if recommended by the adjudicator, is eligible to compete in the Provincial Finals in the Senior Viola, Cello, Double Bass Recital Scholarship category. One District Winner from Provincial Classes 30100, 30120, 30400, or 30420, if recommended by the adjudicator, is eligible to compete in the Provincial Finals in the Senior Strings Concert Scholarship category. One District Winner from Provincial Classes 30002, 30102, 30202, 30302, 30382, 30402, 30502, or 30602, if recommended by the adjudicator, is eligible to compete in the Provincial Finals in the Intermediate Violin Scholarship category. One District Winner from Provincial Classes 30022, 30042, 30062, 30122, 30222, 30322, 30392, 30422, 30522, or 30622, if recommended by the adjudicator, is eligible to compete in the Provincial Finals in the Intermediate Viola, Cello, Double Bass Scholarship category. One District Winner from Provincial Classes 30505, 30525, 30545, 30565, 30605, or 30625, if recommended by the adjudicator, is eligible to compete in the Provincial Finals -

Stars of Tomorrow: Double Bass Showcase 1:00 PM – Francis Auditorium

HEIFETZ 2019 FESTIVAL OF CONCERTS – WEEK VI THURSDAY, AUGUST 8 – Stars of Tomorrow: Double Bass Showcase 1:00 PM – Francis Auditorium Terzetto in C major, Op. 74 Antonín Dvořák I. Introduzione. Allegro ma non troppo (1841–1904) II. Larghetto Spotsylvania Trio Sara Maxman, violin Louisa Pang, violin Kate Moran, viola String Quartet No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 12 Felix Mendelssohn IV. Molto allegro e vivace (1809–1847) Rockbridge Quartet Esme Arias-Kim, violin Tommu Su, violin Adam Savage, viola Angeline Kiang, cello Piano Quintet in A major, D. 667 (“Trout”) Franz Schubert IV. Tema con variazioni. Andantino – Allegretto (1797–1828) Frederick Quintet Angela (Sin Ying) Chan, violin Zhen Huang, viola Zhihao Wu, cello Jesse Lu, double bass Rohan De Silva, piano Piano Quintet in C minor Ralph Vaughan Williams I. Allegro con fuoco (1872–1958) Beverley Quintet Eliane Menzel, violin Mikel Rollet, viola Alex Fowler, cello Alexis Schulte-Albert, double bass Zhenni Li-Cohen, piano Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 Felix Mendelssohn II. Andante con moto tranquillo (1809–1847) IV. Finale. Allegro assai appassionato Danny (Yehun) Jin, violin Dominic Lee, cello David Ji, piano Intermission Romanze (Albumblatt), WWV 94 Richard Wagner (1813–1883) arr. August Wilhelmj (1845–1908) Julia Schilz, violin Rohan De Silva, piano Gran duo concertante Giovanni Bottesini (1821–1889) New Street Trio Athena (Suet Yin) Shiu, violin Victor (Sze Hei) Lee, double bass Miki Sawada, piano Viola Sonata No. 2 in E-flat major, Op. 120 No. 2 Johannes Brahms I. Allegro amabile (1833–1897) Sophia Torres, viola Miki Sawada, piano Sonata for Double Bass and Piano Paul Hindemith I. -

The Rebecca Clarke Society Newsletter

The Rebecca Clarke Society Newsletter February 2012 Volume 7 From our President , Liane Curtis Dear Friends and Supporters! Clarke's music from all far -flung We have not produced a corners of the globe: Japan, newsletter for some time. That Australia, South Africa, and The is not due to a lack of news, but Rebecca Clarke Society rather the opposite! So much supported performances and has been going on that it is hard Master Classes featuring her to stay on top of everything. music in China. More performances of the Last year we celebrated the orchestration of Clarke's Viola 125 th anniversary of Clarke's Sonata have taken place – in birth, so it seemed important to Bartlesville, OK; Stockholm, get a newsletter out and get Sweden; Eskişehir, Turkey (the back in touch with our many Only known photo of Anadolu Symphony Orchestra supporters (and welcome new Clarke playing the viola, with soloist Esra Pehlivanli ), and ones as well!). from the mid-1920s the Chamber Orchestra of the We look forward to hearing Springs in Colorado Springs, CO your insights, news, and ideas (with Cathy Hanson, viola) and for the newsletter (should we Contents in this newsletter we report on have a newsletter? Or should two upcoming performances. we just be tweeting???), as well Performances of the Sonata for Viola and Orchestra 1 We continue to receive as ideas for the Clarke Society. reports of performances of Please enjoy! A Conversation with Michael Beckerman 2 Clarke featured in China 4 West -Coast Premiere of Clarke’s Viola Sonata with Orchestra Problems of Clarke’s estate examined in article 4 The North State Symphony will give by Maestro Kyle Wiley Pickett ) is the the West Coast Premiere of Rebecca third orchestra to perform Ruth Clarke’s Sonata for Viola and Lomon’s orchestration of the Clarke. -

Sonata No. 2 in G Minor for Viola and Piano

The American Viola Society Sonata No. 2 for viola and piano Fidelis Zitterbart Jr. (1845-1915) AVS Publications 041 Preface Born into a musical family in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1845, Fidelis Zitterbart Jr. trained there as a violinist before heading to Dresden at age sixteen for further studies.1 Upon his return to the United States, he performed as a violinist and violist with organizations in New York; he is listed as a member of the viola section during the 1869–70 season of the New York Philharmonic as well as violist during the second season of the Onslow Quintette Club.2 Zitterbart returned to Pittsburgh in 1873 to teach at the American Conservatory of Music, and he remained there as an active part of Pittsburgh’s musical life until his death in 1915. In addition to his work as a performer and teacher, Zitterbart was a prolific composer. He left nearly fifteen hundred compositions, the manuscripts of which now reside in the Special Collections Department, Hillman Library, University of Pittsburgh. The collection contains a remarkable number of compositions for viola: nearly fifty works for viola and piano as well as small-ensemble pieces that include the viola. Among these are thirteen sonatas for viola and piano, the first dating from 1875—the earliest known American viola sonata—which is dedicated to George Matzka, the former principal violist of the New York Philharmonic. The Sonata No. 2 in G Minor, dated August 31, 1897, is the second of Zitterbart’s four-movement viola sonatas (an earlier two-movement sonata dated May 24, 1886, is also labeled as No. -

Program Notes for a Viola Recital Victoria D

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Summer 7-8-2016 Program Notes For A Viola Recital Victoria D. Moore [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Moore, Victoria D. "Program Notes For A Viola Recital." (Summer 2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROGRAM NOTES FOR A VIOLA GRADUATE RECITAL by Victoria Moore B.A, Western Illinois University, 2012 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale August 2016 PROGRAM NOTES FOR A VIOLA GRADUATE RECITAL By Victoria Moore A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music Approved by: Edward Benyas, Chair Dr. Douglas Worthen Dr. Jessica Butler Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 12, 2016 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF VICTORIA MOORE, for the Master of Music degree in MUSIC, presented on MAY 12, 2016, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: PROGRAM NOTES FOR VIOLA GRADUATE RECITAL MAJOR PROFESSOR: Metiney Moore This research paper provides extended program notes relating to the pieces performed on Victoria Moore’s Graduate Viola Recital, which was presented on May 12, 2016. Pieces performed on the recital were Darius Milhaud’s Quatre Visages for Viola and Piano Op. -

Lionel Tertis, York Bowen, and the Rise of the Viola

THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by WILLIAM KENTON LANIER B.A., Thomas Edison State University, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2020 © 2020 WILLIAM KENTON LANIER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND William Kenton Lanier, Candidate for the Master of Music Degree in Musicology University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2020 ABSTRACT The viola owes its current reputation largely to the tireless efforts of Lionel Tertis (1876-1975), who, perhaps more than any other individual, brought the viola to light as a solo instrument. Prior to the twentieth century, numerous composers are known to have played the viola, and some even preferred it, but none possessed the drive or saw the necessity to establish it as an equal solo counterpart to the violin or cello. Likewise, no performer before Tertis had established themselves as a renowned exponent of the viola. Tertis made it his life’s work to bring the viola to the fore, and his musical prowess and technical ability on the instrument gave him the tools to succeed. Tertis was primarily a performer, thus collaboration with composers also comprised a necessary element of his viola crusade. He commissioned works from several British composers, including one of the first and most prolific composers for the viola, York Bowen (1884-1961). -

(Of(R) Viola) and Piano Op

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: November 18, 2004 I, Kyung ju Lee _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Viola Performance It is entitled: An analysis and comparison of the clarinet and viola versions of the Two sonatas for clarinet (or Viola) And piano Op.120 by Johannes Brahms. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Catharine Carroll Lee Fiser Steven Cohen 2 AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF THE CLARINET AND VIOLA VERSION OF THE TWO SONATAS FOR CLARINET (OR VIOLA) AND PIANO OP. 120 BY JOHANNES BRAHMS. A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2004 by Kyungju Lee B.M., Yeungnam University, 1996 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 A.D., University of Cincinnati, 2002 Committee Chair: Catharine Carroll, D.M.A. 2 3 ABSTRACT Johannes Brahms was one of the first composers to appreciate fully the viola’s potential, allowing the instrument a chance to shine in his chamber music. Although Brahms’ Two Sonatas in f-minor and E-flat major, Op.120, were originally written for clarinet and piano, they are also greatly loved in the viola repertoire. Upon examination of the clarinet and viola versions of the sonatas, Brahms seems to have been keenly aware of the potential of each instrument. He intentionally sought different effects from these two instruments by composing two different versions. -

Passacaglia on an Old English Tune for Viola (Or Cello) and Piano

Passacaglia on an Old English Tune for Viola (or Cello) and Piano Program Notes: Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) is now recognized as a significant composer of the first half of the twentieth cen- tury. Born in Harrow, England, to an American father and a German mother, she was educated at London’s Royal College of Music, where she was the first woman composition student of Sir Charles Stanford. She achieved fame as a composer with her Viola Sonata (1919) and Piano Trio (1921), both written for competitions sponsored by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. Throughout the 1920s Clarke continued to write chamber music and songs, much of it for her fellow performers. Clarke also had a long career as a professional violist; in 1913 she was one of the first women to be admitted to the Queen’s Hall Orchestra. Based in London from 1924 to 1939, she toured exten- sively, performing with a number of ensembles, and broadcasting on the BBC. The onset of World War II in 1939 found her visiting in the U.S., where she remained. By 1942 she had completed ten more compositions, and in 1944 she married pianist James Friskin, who had been a fellow student at the Royal College, and settled with him in New York City where she lived until her death at age 93. While she achieved some recognition as a composer in her lifetime, Clarke often felt conflicted about compos- ing. Her use of the pseudonym “Anthony Trent” in 1918 for her (still unpublished) piece Morpheus for Viola and Piano, and her difficulty in finding publishers for her music (even after the success of her Viola Sonata) illustrate some of the many ways that gender affected her career trajectory and her self-image as a composer.