Public Cash for Oil and Gas: Mapping Federal Fiscal Support for Fossil Fuels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts and Mitigations of in Situ Bitumen Production from Alberta Oil Sands

Impacts and Mitigations of In Situ Bitumen Production from Alberta Oil Sands Neil Edmunds, P.Eng. V.P. Enhanced Oil Recovery Laricina Energy Ltd. Calgary, Alberta Submission to the XXIst World Energy Congress Montréal 2010 - 1 - Introduction: In Situ is the Future of Oil Sands The currently recognized recoverable resource in Alberta’s oil sands is 174 billion barrels, second largest in the world. Of this, about 150 billion bbls, or 85%, is too deep to mine and must be recovered by in situ methods, i.e. from drill holes. This estimate does not include any contributions from the Grosmont carbonate platform, or other reservoirs that are now at the early stages of development. Considering these additions, together with foreseeable technological advances, the ultimate resource potential is probably some 50% higher, perhaps 315 billion bbls. Commercial in situ bitumen recovery was made possible in the 1980's and '90s by the development in Alberta, of the Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD) process. SAGD employs surface facilities very similar to steamflooding technology developed in California in the ’50’s and 60’s, but differs significantly in terms of the well count, geometry and reservoir flow. Conventional steamflooding employs vertical wells and is based on the idea of pushing the oil from one well to another. SAGD uses closely spaced pairs of horizontal wells, and effectively creates a melt cavity in the reservoir, from which mobilized bitumen can be collected at the bottom well. Figure 1. Schematic of a SAGD Well Pair (courtesy Cenovus) Economically and environmentally, SAGD is a major advance compared to California-style steam processes: it uses about 30% less steam (hence water and emissions) for the same oil recovery; it recovers more of the oil in place; and its surface impact is modest. -

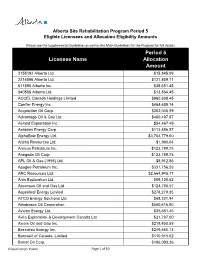

Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts

Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts Please see the Supplemental Guidelines as well as the Main Guidelines for the Program for full details Period 5 Licensee Name Allocation Amount 2155192 Alberta Ltd. $15,845.09 2214896 Alberta Ltd. $121,809.11 611890 Alberta Inc. $35,651.45 840586 Alberta Ltd. $13,864.45 ACCEL Canada Holdings Limited $960,608.45 Conifer Energy Inc. $464,459.14 Acquisition Oil Corp. $302,046.99 Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd. $460,497.87 Aeneid Exploration Inc. $54,467.49 Aeraden Energy Corp. $113,886.57 AlphaBow Energy Ltd. $3,704,779.60 Altima Resources Ltd. $1,980.64 Amicus Petroleum Inc. $123,789.75 Anegada Oil Corp. $123,789.75 APL Oil & Gas (1998) Ltd. $8,912.86 Apogee Petroleum Inc. $331,756.53 ARC Resources Ltd. $2,664,945.71 Artis Exploration Ltd. $89,128.62 Ascensun Oil and Gas Ltd. $124,780.07 Aspenleaf Energy Limited $278,279.35 ATCO Energy Solutions Ltd. $68,331.94 Athabasca Oil Corporation $550,616.80 Avalon Energy Ltd. $35,651.45 Avila Exploration & Development Canada Ltd $21,787.00 Axiom Oil and Gas Inc. $219,850.59 Baccalieu Energy Inc. $249,560.13 Barnwell of Canada, Limited $110,915.62 Barrel Oil Corp. $196,083.36 #Classification: Public Page 1 of 10 Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts Please see the Supplemental Guidelines as well as the Main Guidelines for the Program for full details Period 5 Licensee Name Allocation Amount Battle River Energy Ltd. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 Annual Report MISSION Our mission is to facilitate innovation, collaborative research and technology development, demonstration and deployment for a responsible Canadian hydrocarbon energy industry. VISION Our vision is to help Canada become a global hydrocarbon energy technology leader. Contact Us For further information please contact: PTAC Petroleum Technology Alliance Canada Suite 400, Chevron Plaza, 500 Fifth Avenue SW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2P 3L5 MAIN: 403-218-7700 FAX: 403-920-0054 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB SITE: www.ptac.org PERSONNEL SOHEIL ASGARPOUR BRENDA BELLAND SUSIE DWYER LORIE FREI MARC GODIN President Manager, Knowledge Centre Innovation and Technology R&D Initiatives Assistant and Technical Advisor (403) 218-7701 (403) 218-7712 Development Web Site (403) 870-5402 [email protected] [email protected] Coordinator Administrator marc.godin@portfi re.com (403) 218-7708 (403) 218-7707 [email protected] [email protected] ARLENE MERLING TRUDY HIGH BOBBI SINGH LAURA SMITH TANNIS SUCH Director, Operations Administrative and Registration Accountant Controller Manager, Environmental (403) 218-7702 Coordinator (403) 218-7723 (403) 218-7701 Research [email protected] (403) 218-7711 [email protected] [email protected] Initiatives [email protected] (403) 218-7703 [email protected] PETROLEUM TECHNOLOGY ALLIANCE CANADA 2010 ANNUAL REPORT 3 Message from the Board A New Decade – A New Direction 2010 proved to be a turning point for PTAC as we redeined our role and PTAC Technology Areas set new strategies in motion. Over the past year PTAC has achieved goals in diverse areas of our organization: improving our inances, rebalancing our MANAGE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS project portfolios to address a broad spectrum of needs, leveraging support • Emission Reduction / Eco-eficiency for ield implementations, and building a measurably more effective and • Energy Eficiency eficient organization. -

Emerging Oil Sands Producers

RBC Dominion Securities Inc. Emerging Oil Sands Producers Mark Friesen (Analyst) (403) 299-2389 Initiating Coverage: The Oil Sands Manifesto [email protected] Sam Roach (Associate) Investment Summary & Thesis (403) 299-5045 We initiate coverage of six emerging oil sands focused companies. We are bullish with [email protected] respect to the oil sands sector and selectively within this peer group of new players. We see decades of growth in the oil sands sector, much of which is in the control of the emerging companies. Our target prices are based on Net Asset Value (NAV), which are based on a long-term flat oil price assumption of US$85.00/bbl WTI. The primary support for our December 13, 2010 valuations and our recommendations is our view of each management team’s ability to execute projects. This report is priced as of market close December 9, 2010 ET. We believe that emerging oil sands companies are an attractive investment opportunity in the near, medium and longer term, but investors must selectively choose the All values are in Canadian dollars companies with the best assets and greatest likelihood of project execution. unless otherwise noted. For Required Non-U.S. Analyst and Investment Highlights Conflicts Disclosures, please see • page 198. MEG Energy is our favourite stock, which we have rated as Outperform, Above Average Risk. We have also assigned an Outperform rating to Ivanhoe Energy (Speculative Risk). • We have rated Athabasca Oil Sands and Connacher Oil & Gas both as Sector Perform, (Above Average Risk). We have also assigned a Sector Perform rating to SilverBirch Energy (Speculative Risk). -

Notice of Applications Connacher Oil and Gas Limited Great Divide Expansion Project Athabasca Oil Sands Area

NOTICE OF APPLICATIONS CONNACHER OIL AND GAS LIMITED GREAT DIVIDE EXPANSION PROJECT ATHABASCA OIL SANDS AREA ENERGY RESOURCES CONSERVATION BOARD APPLICATION NO. 1650859 ALBERTA ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND ENHANCEMENT ACT APPLICATION NO. 003-240008 WATER ACT FILE NO. 00271543 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT The Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB/Board) has received Application No. 1650859 and Alberta Environment (AENV) has received Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act (EPEA) Application No. 003-240008 and Water Act File No. 00271543 from Connacher Oil and Gas Limited (Connacher) for approval of the proposed Great Divide Expansion Project (the Project). This notice is to advise interested parties that the applications are available for viewing and that the ERCB, AENV, and other government departments are now undertaking a review of the applications and associated environmental impact assessment (EIA). Description of the Project Connacher has applied to construct, operate, and reclaim an in-situ oil sands project about 70 kilometres (km) south of the City of Fort McMurray in Townships 81, 82, and 83, Ranges 11 and 12, West of the 4th Meridian. Construction of the Project is proposed to begin in 2011, with increased production starting by 2012. The proposed Project would amalgamate Connacher’s existing Great Divide (EPEA Approval No. 223216-00-00) and Algar (EPEA Approval No. 240008-00-00) projects which were each designed to produce 1600 cubic metres per day (m3/day) (10 000 barrels per day [bbl/d]) of bitumen. The proposed Project would also increase Connacher’s bitumen production capacity to 7000 m3/day (44 000 bbl/d) at peak production using the in situ steam assisted gravity drainage (SADG) thermal recovery process. -

Alberta Oil Sands Quarterly Update Fall 2013

ALBERTA OIL SANDS INDUSTRY QUARTERLY UPDATE FALL 2013 Reporting on the period: June 18, 2013, to Sep. 17, 2013 2 ALBERTA OIL SANDS INDUSTRY QUARTERLY UPDATE Canada has the third-largest oil methods. Alberta will continue to rely reserves in the world, after Saudi to a greater extent on in situ production Arabia and Venezuela. Of Canada’s in the future, as 80 per cent of the 173 billion barrels of oil reserves, province’s proven bitumen reserves are 170 billion barrels are located in too deep underground to recover using All about Alberta, and about 168 billion barrels mining methods. are recoverable from bitumen. There are essentially two commercial This is a resource that has been methods of in situ (Latin for “in the oil sands developed for decades but is now place,” essentially meaning wells are gaining increased global attention Background of an used rather than trucks and shovels). as conventional supplies—so-called In cyclic steam stimulation (CSS), important global resource “easy” oil—continue to be depleted. high-pressure steam is injected into The figure of 168 billion barrels directional wells drilled from pads of bitumen represents what is for a period of time, then the steam considered economically recoverable is left to soak in the reservoir for a with today’s technology, but with period, melting the bitumen, and new technologies, this reserve then the same wells are switched estimate could be significantly into production mode, bringing the increased. In fact, total oil sands bitumen to the surface. reserves in place are estimated at 1.8 trillion barrels. -

Alberta Oil Sands Industry Quarterly Update

ALBERTA OIL SANDS INDUSTRY QUARTERLY UPDATE WINTER 2013 Reporting on the period: Sep. 18, 2013 to Dec. 05, 2013 2 ALBERTA OIL SANDS INDUSTRY QUARTERLY UPDATE Canada has the third-largest oil methods. Alberta will continue to rely All about reserves in the world, after Saudi to a greater extent on in situ production Arabia and Venezuela. Of Canada’s in the future, as 80 per cent of the 173 billion barrels of oil reserves, province’s proven bitumen reserves are the oil sands 170 billion barrels are located in too deep underground to recover using Background of an Alberta, and about 168 billion barrels mining methods. are recoverable from bitumen. There are essentially two commercial important global resource This is a resource that has been methods of in situ (Latin for “in developed for decades but is now place,” essentially meaning wells are gaining increased global attention used rather than trucks and shovels). as conventional supplies—so-called In cyclic steam stimulation (CSS), “easy” oil—continue to be depleted. high-pressure steam is injected into The figure of 168 billion barrels TABLE OF CONTENTS directional wells drilled from pads of bitumen represents what is for a period of time, then the steam considered economically recoverable is left to soak in the reservoir for a All about the oil sands with today’s technology, but with period, melting the bitumen, and 02 new technologies, this reserve then the same wells are switched estimate could be significantly into production mode, bringing the increased. In fact, total oil sands Mapping the oil sands bitumen to the surface. -

2020-03-24 the Oilsands in a Carbon-Constrained Canada FINAL

The oilsands in a carbon- constrained Canada The collision course between overall emissions and national climate commitments Benjamin Israel Jan Gorski, Nina Lothian, Chris Severson-Baker, Nikki Way February 2020 updated March 2020 Photo: Kris Krüg, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 The oilsands in a carbon- constrained Canada The collision course between overall emissions and national climate commitments Benjamin Israel Jan Gorski, Nina Lothian, Chris Severson-Baker and Nikki Way February 2020 updated March 2020 Production management: Michelle Bartleman Editors: Michelle Bartleman, Roberta Franchuk, ISBN 1-897390-44-0 Sarah MacWhirter Contributors: Nichole Dusyk, Simon Dyer, The Pembina Institute Duncan Kenyon, Morrigan Simpson-Marran 219 19 Street NW Calgary, AB ©2020 The Pembina Institute Canada T2N 2H9 All rights reserved. Permission is granted to Phone: 403-269-3344 reproduce all or part of this publication for non- commercial purposes, as long as you cite the Additional copies of this publication may be source. downloaded from the Pembina Institute website, www.pembina.org. Recommended citation: Israel, Benjamin. The oilsands in a carbon-constrained Canada. The Pembina Institute, 2020. Pembina Institute The oilsands in a carbon-constrained Canada | ii About the Pembina Institute The Pembina Institute is a national non-partisan think tank that advocates for strong, effective policies to support Canada’s clean energy transition. We employ multi-faceted and highly collaborative approaches to change. Producing credible, evidence-based research and analysis, we consult directly with organizations to design and implement clean energy solutions, and convene diverse sets of stakeholders to identify and move toward common solutions. ————————————————— pembina.org ————————————————— twitter.com/pembina facebook.com/pembina.institute Donate to the Pembina Institute Together, we can lead Canada's transition to clean energy. -

Canadian Oil Sands Production and Emissions Outlook (2020-2039)

STUDY NO. 191 AUGUST 2020 CANADIAN OIL SANDS PRODUCTION AND EMISSIONS OUTLOOK (2020-2039) 3512 - 33 Street NW, #150, Calgary, AB T2L 2A6 350 Sparks Street, #805, Ottawa, ON K1R 7S8 403.282.1231 | www.ceri.ca | [email protected] @ceri_canada Canadian Energy Research Institute CANADIAN OIL SANDS PRODUCTION AND EMISSIONS OUTLOOK (2020-2039) Canadian Oil Sands Production and Emissions Outlook (2020-2039) Author: Dinara Millington Recommended Citation (Author-date style): Millington, D. 2020. “Canadian Oil Sands Production and Emissions Outlook (2020-2039).” Study No. 191. Calgary, AB: Canadian Energy Research Institute. https://ceri.ca/assets/files/Study 191 Full Report.pdf Recommended Citation (Numbered style): D. Millington, “Canadian Oil Sands Production and Emissions Outlook (2020-2039),” Canadian Energy Research Institute, Calgary, AB, Study No. 191, 2020. URL: https://ceri.ca/assets/files/Study 191 Full Report.pdf Copyright © Canadian Energy Research Institute, 2020 Sections of this study may be reproduced in magazines and newspapers with acknowledgment to the Canadian Energy Research Institute August 2020 Printed in Canada Acknowledgements: The author of this report would like to extend her thanks and sincere gratitude to all CERI staff that provided insightful comments and essential data inputs required for the completion of this report, as well as those involved in the production, reviewing and editing of the material, including but not limited to Hamid Rahmanifard, Toufigh Bararpour, Allan Fogwill and Kelsey Marklund. ABOUT THE CANADIAN ENERGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Founded in 1975, the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) is an independent, registered charitable organization specializing in the analysis of energy economics and related environmental policy issues in the energy production, transportation, and consumption sectors. -

News Release ______

__________________________________________________________________________________________ NEWS RELEASE __________________________________________________________________________________________ CONNACHER OIL AND GAS LIMITED ANNOUNCES CREDITOR AND COURT APPROVAL OF RESTRUCTURING Calgary, Alberta, October 4, 2018 – Connacher Oil and Gas Limited (“Connacher” or the “Company”) is pleased to announce the approval of the Company’s Amended and Restated Plan of Compromise and Arrangement (the “Plan”) by the required majorities of affected creditors and the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta (the “Court”) in the Company’s proceedings under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (the “CCAA”). As previously announced, the Plan effects a transaction to sell the Company to East River Oil and Gas Ltd. (“East River”) through the acquisition of Connacher’s share capital. The resolution (the “Plan Resolution”) approving the Plan pursuant to the CCAA was approved by 100% of the Company’s first lien lenders (the “First Lien Lenders”) and 100% of the Company’s general unsecured creditors (the “General Creditors”) who were present and voted in person or by proxy on the Plan Resolution at the creditors’ meetings held on October 3, 2018, in accordance with the Creditors’ Meetings Order granted by the Court on August 22, 2018. Following the positive vote at the creditors’ meetings, the Court sanctioned the Plan on October 4, 2018. The Company is now working towards satisfying conditions precedent to the Plan and consummating the transaction with East River, which is currently expected to occur between November 8, 2018 and November 15, 2018, subject to the right of East River to extend the closing date in certain circumstances. The approval of the Plan by affected creditors and subsequent Court sanction of the Plan, are key steps towards the Company’s implementation of the Plan transaction with East River and its emergence from protection under the CCAA. -

Oil and Gas Players Back in the Game Message from the President

iradesso QUARTERLY Q1 2008 CANADIAN OIL & GAS COMPARISON FINANCIAL & OPERATING RESULTS for 65 Juniors & 27 Intermediates Featuring Updated Profiles From Juniors & Intermediates Oil and gas players back in the game Message from the President OIL AND GAS PLAYERS Round the Bases For Investors What a difference a year makes. While most oil and gas players of 2008, the second highest quarterly netback on record since struck out in the stock market in 2007, almost everyone is back we started tracking the numbers in the second quarter of in the game so far in 2008. All but eight of the 92 juniors and 2003. The netback for the intermediates was even higher at intermediates compared in this iQ Report experienced an increase $30.36 per boe. in their share or unit price in the first five months of the year. The The Canadian energy sector saw its fair share of adversity in average intermediate producer has produced a total return since 2007. This adversity weeded out some weaker players and set up the beginning of 2008 of 46 percent while the average junior others to come out even stronger. Now companies with reputable producer has returned 49 percent. We’ve defined intermediates as management teams, strong balance sheets and quality assets companies that produce between 10,000 and 100,000 boe/d while are enjoying renewed access to capital, another key component juniors produce between 500 and 10,000 boe/d. We decided it that drives growth in the sector. When a company gets a capital is time to drop the shrinking energy trust category from our report advantage, options open up for making acquisitions and expanding and incorporate remaining trusts into the junior and intermediate drilling programs. -

In Situ Oil Sands Technology Trends

STUDY NO. 193 DECEMBER 2020 IN SITU OIL SANDS TECHNOLOGY TRENDS 3512 - 33 Street NW, #150, Calgary, AB T2L 2A6 350 Sparks Street, #805, Ottawa, ON K1R 7S8 403.282.1231 | www.ceri.ca | [email protected] @ceri_canada Canadian Energy Research Institute In Situ Oil Sands Technology Trends Authors: Evar Umeozor, Madie Zamzadeh, Dinara Millington Recommended Citation (Author-date style): Umeozor, Evar, Madie Zamzadeh, and Dinara Millington. 2021. “In Situ Oil Sands Technology Trends.” Study No. 193 Calgary, AB: Canadian Energy Research Institute. https://ceri.ca/assets/files/Study_193_Full_Report.pdf Recommended Citation (Numbered style): E. Umeozor, M. Zamzadeh and D. Millington, “In Situ Oil Sands Technology Trends,” Canadian Energy Research Institute, Calgary, AB, Study No. 193, 2021. URL: https://ceri.ca/assets/files/Study_193_Full_Report.pdf Copyright © Canadian Energy Research Institute, 2021 Sections of this study may be reproduced in magazines and newspapers with acknowledgment to the Canadian Energy Research Institute January 2021 Printed in Canada Acknowledgements: The authors of this report would like to extend their thanks and sincere gratitude to all CERI staff involved in the production and editing of the material. ABOUT THE CANADIAN ENERGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Founded in 1975, the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) is an independent, registered charitable organization specializing in the analyses of economic and environmental issues in the energy production, transportation and consumption sectors. Our studies examine the most relevant energy issues affecting Canadians, painting a comprehensive picture of the impact policies and business decisions can have so that decision-makers in government, industry and other market segments can make sound decisions to help move Canada forward.