THOMAS HARDY Under the Greenwood Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Thomas Hardy's Novels : an Interpretative Study

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. WOMEN IN THOMAS HARDY'S NOVEIS: AN INTERPRETATIVE STUDY . A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the r equir ements for t he degree of Master of Arts in English at Massey University. D O R O T H Y M O R R I S O N • 1970. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Introduction. Chapter 1 • Plot and Character, p.8. Chapter 2. Women ?JlC. Nature, p.1 2 . Chanter '3 . Women and Class, p . 31 • Chapter 4. Women and Morality, P• 43. Chapter 5. Love and Marriage, p.52. Chapter 6. Marriage and Divorce, p.68. Conclusion, p.90. B_:_ bl i ography, n. 9/i. WOMEN IN THO:M..AS HARDY'S NOVELS: AN INTERPRETATIVE STUDY. INTRODUCTION. When one begins a study of the women in Hardy's novels one discovers critical views of great diversity. There are features of Hardy's work which received favourable comment then as now; his descriptions of nature for instance, and his rustic characters have appealed to most critics over the years. But his philosophical and social cormnent have drawn criticism ranging from the virulent to the scornful. In particular his attitude to and treatment of love and marriage relationships have been widely argued, and it is the women concerned who have been assessed in the most surprising and contradictory manner. -

Two on a Tower Online

hvWCu [Pdf free] Two on a Tower Online [hvWCu.ebook] Two on a Tower Pdf Free Thomas Hardy *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Thomas Hardy 2013-05-09Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.69 x .41 x 7.44l, .74 #File Name: 148492407X180 pagesTwo on a Tower | File size: 26.Mb Thomas Hardy : Two on a Tower before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Two on a Tower: 6 of 6 people found the following review helpful. Sadly OverlookedBy Bill R. MooreTwo on a Tower is among Thomas Hardy's least known novels, and though not in his top tier, is excellent and would be nearly anyone else's best. It certainly deserves a far wider readership, as it has both many usual strengths and is in several ways unique, making it worthwhile for both fans and others.The main unique factor is the astronomy focus. Hardy had significant interest in and knowledge of astronomy, which pops up in his work here and there, but only Two deals with it extensively. The main male character is an astronomer, and the field gets considerable attention; readers can learn a fair amount about it from Two, as there are many technical terms, historical references, and other descriptions. The focus is indeed so strong that Two might almost be called proto-science fiction; astronomy is not integral to the plot, but its background importance is very high. Hardy was no scientist but researched extensively, taking great pains to be accurate, and it shows. -

Of Desperate Remedies

Colby Quarterly Volume 15 Issue 3 September Article 6 September 1979 Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Remedies Lawrence Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 15, no.3, September 1979, p.194-200 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Jones: Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Reme Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Remedies by LAWRENCE JONES N THE autumn of 1884, Thomas Hardy was approached by the re I cently established publishing firm of Ward and Downey concerning the republication of his first novel, Desperate Remedies. Although it had been published in America by Henry Holt in his Leisure Hour series in 1874, the novel had not appeared in England since the first, anony mous publication by Tinsley Brothers in 1871. That first edition, in three volumes, had consisted of a printing of 500 (only 280 of which had been sold at list price). 1 Since that time Hardy had published eight more novels and had established himself to the extent that Charles Kegan Paul could refer to him in the British Quarterly Review in 1881 as the true "successor of George Eliot," 2 and Havelock Ellis could open a survey article in the Westminster Review in 1883 with the remark that "The high position which the author of Far from the Madding Crowd holds among contemporary English novelists is now generally recognized." 3 As his reputation grew, his earlier novels were republished in England in one-volume editions: Far from the Madding Crowd, A Pair of Blue Eyes, and The Hand ofEthelberta in 1877, Under the Greenwood Tree in 1878, The Return of the Native in 1880, A Laodicean in 1882, and Two on a Tower in 1883. -

Music Inspired by the Works of Thomas Hardy

This article was first published in The Hardy Review , Volume XVI-i, Spring 2014, pp. 29-45, and is reproduced by kind permission of The Thomas Hardy Association, editor Rosemarie Morgan. Should you wish to purchase a copy of the paper please go to: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ttha/thr/2014/00000016/0 0000001/art00004 LITERATURE INTO MUSIC: MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE WORKS OF THOMAS HARDY Part Two: Music composed after Hardy’s lifetime CHARLES P. C. PETTIT Part One of this article was published in the Autumn 2013 issue. It covered music composed during Hardy’s lifetime. This second article covers music composed since Hardy’s death, coming right up to the present day. The focus is again on music by those composers who wrote operatic and orchestral works, and only mentions song settings of poems, and music in dramatisations for radio and other media, when they were written by featured composers. Hardy’s work is seen to have inspired a wide variety of music, from full-length operas and musicals, via short pieces featuring particular fictional episodes, to ballet music and purely orchestral responses. Hardy-inspired compositions show no sign of reducing in number over the decades. However despite the quantity of music produced and the quality of much of it, there is not the sense in this period that Hardy maintained the kind of universal appeal for composers that was evident during the last two decades of his life. Keywords : Thomas Hardy, Music, Opera, Far from the Madding Crowd , Tess of the d’Urbervilles , Alun Hoddinott, Benjamin Britten, Elizabeth Maconchy In my earlier article, published in the Autumn 2013 issue of the Hardy Review , I covered Hardy-inspired music composed during Hardy’s lifetime. -

Pessimism in the Novels of Thomas Hardy Submitted To

PESSIMISM IN THE NOVELS OF THOMAS HARDY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY LOTTIE GREENE REID DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 195t \J p PREFACE "Of all approbrious names,11 saya Florence Emily Hardy, "Hardy resented most 'pessimist.1Hl Yet a thorough atudy of his novels will certainly convince one that his attitude to ward life is definitely pessimistic* Mrs. Hardy quotes him as saying: "My motto is, first correctly diagnose the complaint — in this caae human Ills —- and ascertain the causes then set about finding a remedy if one exists.1'2 According to Hardy, humanity is ill. In diagnosing the case, he is not much concerned with the surface of things, but is more interested in probing far below the surface to find the force behind them. Since this force in his novels is always Fate, and since he is always certain to make things end tragi cally, the writer of this study will attempt to show that he well deserves the name, "pessimist." In this study the writer will attempt to analyze Hardy1 s novels in order to ascertain the nature of his pessimism, as well as point out the techniques by which pessimism is evinced in his novels. In discussing the causes of pessimism, the writer ^■Florence E. Hardy, "The Later Years of Thomas Hardy," reviewed by Wilbur Cross, The Yale Review, XX (September, 1930), p. 176. ' 2Ibid. ii ill deems it necessary to consider Hardy's personality, influences, and philosophy, which appear to be the chief causes of the pes simistic attitude taken by him. -

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY By the same author THE MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE (Macmillan Critical Commentaries) A HARDY COMPANION ONE RARE FAIR WOMAN Thomas Hardy's Letters to Florence Henniker, 1893-1922 (edited, with Evelyn Hardy) A JANE AUSTEN COMPANION A BRONTE COMPANION THOMAS HARDY AND THE MODERN WORLD (edited,for the Thomas Hardy Society) A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY F. B. Pinion ISBN 978-1-349-02511-4 ISBN 978-1-349-02509-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-02509-1 © F. B. Pinion 1976 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 15t edition 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1976 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Associated companies in New York Dublin Melbourne Johannesburg and Madras SBN 333 17918 8 This book is sold subject to the standard conditions of the Net Book Agreement Quid quod idem in poesi quoque eo evaslt ut hoc solo scribendi genere ..• immortalem famam assequi possit? From A. D. Godley's public oration at Oxford in I920 when the degree of Doctor of Letters was conferred on Thomas Hardy: 'Why now, is not the excellence of his poems such that, by this type of writing alone, he can achieve immortal fame ...? (The Life of Thomas Hardy, 397-8) 'The Temporary the AU' (Hardy's design for the sundial at Max Gate) Contents List of Drawings and Maps IX List of Plates X Preface xi Reference Abbreviations xiv Chronology xvi COMMENTS AND NOTES I Wessex Poems (1898) 3 2 Poems of the Past and the Present (1901) 29 War Poems 30 Poems of Pilgrimage 34 Miscellaneous Poems 38 Imitations, etc. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Miroslav Kohut Gender Relations in the Narrative Organization of Four Short Stories by Thomas Hardy Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2011 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 2 I would like to thank Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. for his valuable advice during writing of this thesis. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Thomas Hardy as an author ..................................................................................... 7 1.2 The clash of two worlds in Hardy‘s fiction ............................................................. 9 1.3 Thomas Hardy and the issues of gender ............................................................... 11 1.4 Hardy‘s short stories ............................................................................................. 14 2. The Distracted Preacher .............................................................................................. 16 3. An Imaginative Woman .............................................................................................. 25 4. The Waiting Supper .................................................................................................... 32 5. A Mere Interlude -

A Laodicean Unabridged

Thomas Hardy COMPLETE CLASSICS A LAODICEAN UNABRIDGED Read by Anna Bentinck Subtitled ‘A Story of To-day’, A Laodicean occupies a unique place in the Thomas Hardy canon. Departing from pre-industrial Wessex, Hardy brings his themes of social constraint, fate, chance and miscommunication to the very modern world of the 1880s – complete with falsified telegraphs, fake photographs, and perilous train tracks. The story follows the life of Paula Power, heiress of her late father’s railroad fortune and the new owner of the medieval Castle Stancy. With the castle in need of restoration, Paula employs architect George Somerset, who soon falls in love with her. However, Paula’s dreams of nobility draw her to another suitor, Captain de Stancy, who is aided by his villainous son, William Dare… Anna Bentinck trained at Arts Educational Schools, London (ArtsEd) and has worked extensively for BBC radio. Her animation voices include the series 64 Zoo Lane (CBeebies). Film credits include the Hammer Horror Total running time: 17:06:20 To the Devil… A Daughter. Her many audiobooks range from Shirley by View our catalogue online at n-ab.com/cat Charlotte Brontë, Kennedy’s Brain by Henning Mankell, Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel, Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys and One Day by David Nicholls to The Bible. For Naxos AudioBooks, she has read Five Children and It, The Phoenix and the Carpet and The Amulet by E. Nesbit and Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Desperate Remedies by Thomas Hardy. 1 A Laodicean 9:15 24 Chapter 11 9:28 2 It is an old story.. -

A Bibliography of the Richard Johnson Collection of Hardyana “Hardy’S Se�Ings Always Intrigued Me” “HARDY’S SETTINGS ALWAYS INTRIGUED ME”

“HARDY’S SETTINGS ALWAYS INTRIGUED ME” A Bibliography of the Richard Johnson Collection of Hardyana “Hardy’s Se�ings Always Intrigued Me” “HARDY’S SETTINGS ALWAYS INTRIGUED ME” A Bibliography of the Richard Johnson Collection of Hardyana Prepared by Lyle Ford and Jan Horner University of Manitoba Libraries 2007 The University of Manitoba Libraries Thomas Hardy Collection: An Introduction _______________________ The start of what was to become an ongoing fascination with the writings of Thomas Hardy came for me in 1949-50 when I was in Grade XII at Gordon Bell High School in Winnipeg. At that time, the English requirement was a double course that represented a third of the year’s curriculum. The required reading novel in the Prose half of the course was The Return of the Native. The poetry selections in the Poetry and Drama half were heavily weighted with Wordsworth but included five or six of Hardy’s poems to represent in part, I suppose, “modern” poetry. I was fortunate to have Gordon (“Pop”) Snider as my English teacher for Grades X through XII at Gordon Bell (the original school at Wolseley and Maryland). Up to that point English classes had involved an interminable run of texts in the “Vitalized English” series that entailed studies of word usage, required 7 readings, and the repetitive study of parts of speech that le� me cold. Snider introduced us to figures of speech in a systematic way in Grade X and from there made literature come alive for me. At the same time, I was completing five years of Latin with W. -

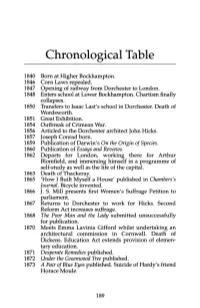

Chronological Table

Chronological Table 1840 Born at Higher Bockhampton. 1846 Corn Laws repealed. 1847 Opening of railway from Dorchester to London. 1848 Enters school at Lower Bockhampton. Chartism finally collapses. 1850 Transfers to Isaac Last's school in Dorchester. Death of Wordsworth. 1851 Great Exhibition. 1854 Outbreak of Crimean War. 1856 Articled to the Dorchester architect John Hicks. 1857 Joseph Conrad born. 1859 Publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species. 1860 Publication of Essays and Reviews. 1862 Departs for London, working there for Arthur Blomfield, and immersing himself in a programme of self-study as well as the life of the capital. 1863 Death of Thackeray. 1865 'How I Built Myself a House' published in Chambers's Journal. Bicycle invented. 1866 J. S. Mill presents first Women's Suffrage Petition to parliament. 1867 Returns to Dorchester to work for Hicks. Second Reform Act increases suffrage. 1868 The Poor Man and the Lady submitted unsuccessfully for publication. 1870 Meets Emma Lavinia Gifford whilst undertaking an architectural commission in Cornwall. Death of Dickens. Education Act extends provision of elemen tary education. 1871 Desperate Remedies published. 1872 Under the Greenwood Tree published. 1873 A Pair of Blue Eyes published. Suicide of Hardy's friend Horace Moule. 189 190 Chronological Table 1874 Publication of Far from the Madding Crowd allows Hardy the financial stability to marry Emma Lavinia Gifford. 1876 Publication of The Hand of Ethelberta. Acquire for the first time a house to themselves, at Sturminster Newton. The Return of the Native written here, and the marriage enters its happiest period. Invention of tele phone and phonograph. -

PDF Download Thomas Hardys Short Stories 1St Edition Ebook

THOMAS HARDYS SHORT STORIES 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Juliette Berning Schaefer | 9781317010425 | | | | | Thomas Hardys Short Stories 1st edition PDF Book Dorchester : The Mayor of Casterbridge. London : First edition in book form. Initially discussed as early as July , the start of the Great War halted production and the actual publication did not begin until December A very good copy. Purdy pp Publisher's original dark green cloth with gilt monogram on upper cover. No Preference. I felt he was completely closed in his own creative dream" , and wrote affectionately of St Helier herself: "Others have done justice to her tireless and intelligent activities on the London County Council. Ours is a black tulip, one-of-a-kind, a copy personally presented to the daughter of a man whom Hardy called friend and neighbor. Limited to sets of which this is number Skip to main content. Housed in a green cloth solander box. Far from the Madding Crowd. First Edition. Hardy, Thomas. Dixon About this Item: London, More information about this seller Contact this seller 8. MacManus Co. Create a Want Tell us what you're looking for and once a match is found, we'll inform you by e-mail. Seller: rare-book-cellar Seller's other items. We buy Thomas Hardy First Editions. Region see all. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab. One of a limited edition of 1, numbered set of which this is number Ended: Sep 30, PDT. Sponsored Listings. Adams, Jr. St Helier wrote a spirited defence of Hardy in a letter to the Daily Chronicle in May , responding to a suggestion that his recently published collection, Life's Little Ironies, ought to be suppressed on the ground of sexual frankness. -

Thomas Hardy, Mona Caird and John

‘FALLING OVER THE SAME PRECIPICE’: it was first published in serial form in Tinsley’s Magazine , The Wing of 5 THOMAS HARDY, MONA CAIRD AND Azrael has only recently been reprinted. The Wing of Azrael deserves to be read in its own right, but it is also JOHN STUART MILL rewarding to read it alongside A Pair of Blue Eyes . Such a comparative reading reveals not only how Caird’s novel is in dialogue with Hardy’s, but also the differences and correspondences in the ways each novelist DEMELZA HOOKWAY engages with the philosophy of John Stuart Mill. This essay will consider how Hardy and Caird evoke, explore and re-work, through their cliff- edge narratives, Millian ideas about how individuals can challenge On July 3 1889, Hardy, by his own arrangement, sat next to Mona Caird customs: the qualities they must have, the strategies they must deploy, at the dinner for the Incorporated Society of Authors. 1 Perhaps one of and the difficulties they must negotiate, in order to carry out experiments their topics of conversation was the reaction to Caird’s recently published in living. Like Hardy, Caird regarded Mill as her intellectual hero. When novel The Wing of Azrael . Like Hardy’s A Pair of Blue Eyes in 1873, The asked by the Women’s Penny Paper in 1890 if she was influenced by any Wing of Azrael features a literal cliffhanger which is a formative event women in forming her views on gender equality she replied ‘“No, not in the life of its heroine. This similarity suggests that Caird, a journalist particularly.