Putonghua-Language Radio Programming in Hong Kong: RTHK and the Putonghua Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media Francis L. F. Lee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.8009 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 9-18 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Francis L. F. Lee, “Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media”, China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2018, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 8009 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. -

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

Experience Lingnan University, Located in Tuen

e r X p i e E n c e Index e l c X Explore Hong Kong 1 E Experience 2 Excel @ 10 E X p l o r e Fast facts 11 L ingn an U ST nive ART rs HE ity RE! L ingn an U ST nive ART rs HE ity RE! Welcome to Hong Kong Experience Lingnan University, located in Tuen Mun, offers a stimulating and thought-provoking liberal arts education. We are the only university in Hong Kong to offer a dedicated liberal arts education. Our goal is to cultivate in our graduates the skills and sensibilities necessary to successfully pursue their career goals and take their place as socially responsible citizens in today’s rapidly evolving global environment. Lively and outward-looking, the university is located on an award-winning campus that visually represents our East-West orientation. Courses are offered by 16 departments in the Faculties of Arts, Business and Social Sciences, the Core Curriculum and General Education Explore Office and two language centres. Hong Kong Mission and vision Lingnan University is committed to the provision of quality education The geographical position of Hong Kong, a vibrant world city situated at the mouth of distinguished by the best liberal arts the Pearl River Delta on the coast of southern China, has made it a gateway between traditions. We adopt a whole-person East and West, turning it into one of the world’s most cosmopolitan metropolises. approach to education that enables our students to think, judge, care Bi-literacy and tri-lingualism thrive in Hong Kong. -

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Legal Hybridity in Hong Kong and Macau Ignazio Castellucci

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:22 p.m. McGill Law Journal Revue de droit de McGill Legal Hybridity in Hong Kong and Macau Ignazio Castellucci Volume 57, Number 4, June 2012 Article abstract The article aims to compare the case of the two Chinese Special Administrative URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013028ar Regions (SARs) of Hong Kong and Macau against the theoretical grid developed DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1013028ar by Vernon V. Palmer to describe the “classical” civil law-common law mixed jurisdictions. The results of the research include an acknowledgement of the See table of contents progressive hybridization of the legal systems of Hong Kong and Macau, hailing from the English common law and the Portuguese civil law tradition, respectively, by infiltration of legal models and ideologies from Mainland Publisher(s) China. The research also leads to a critical revision and refinement of the McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill methodology and tools developed by Palmer in order to make them applicable to a wider range of processes of legal hybridization beyond “classical” mixes, ISSN and to a better appreciation of how transitional political and institutional phases play a critical role inlegal “mixity” or hybridity. 0024-9041 (print) 1920-6356 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Castellucci, I. (2012). Legal Hybridity in Hong Kong and Macau. McGill Law Journal / Revue de droit de McGill, 57(4), 665–720. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013028ar Copyright © Ignazio Castellucci, 2012 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Radio Television Hong Kong

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE This leaflet summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public broadcaster in the HKSAR. Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2010-11, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; maximize return on government funding by further enhancing cost efficiency and productivity; continue to ensure staff handle public funds in a prudent and cost-effective manner; actively explore opportunities in generating revenue for the government from RTHK programmes and contents; provide media coverage and produce special radio, television programmes and related web content for Legislative Council By-Elections 2010, Shanghai Expo 2010, 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou and World Cup in South Africa; and carry out the preparatory work for launching the new digital audio broadcasting and digital terrestrial television services to achieve its mission as the public service broadcaster. -

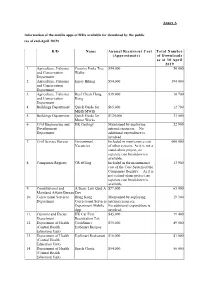

Information of the Mobile Apps of B/Ds Available for Download by the Public (As of End-April 2019)

Annex A Information of the mobile apps of B/Ds available for download by the public (as of end-April 2019) B/D Name Annual Recurrent Cost Total Number (Approximate) of Downloads as at 30 April 2019 1. Agriculture, Fisheries Country Parks Tree $54,000 50 000 and Conservation Walks Department 2. Agriculture, Fisheries Enjoy Hiking $54,000 394 000 and Conservation Department 3. Agriculture, Fisheries Reef Check Hong $39,000 10 700 and Conservation Kong Department 4. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $65,000 12 700 MBIS/MWIS 5. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $120,000 33 000 Minor Works 6. Civil Engineering and HK Geology Maintained by deploying 22 900 Development internal resources. No Department additional expenditure is involved. 7. Civil Service Bureau Government Included in maintenance cost 600 000 Vacancies of other systems. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 8. Companies Registry CR eFiling Included in the maintenance 13 900 cost of the Core System of the Companies Registry. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 9. Constitutional and A Basic Law Quiz A $77,000 65 000 Mainland Affairs Bureau Day 10. Correctional Services Hong Kong Maintained by deploying 19 300 Department Correctional Services internal resources. Department Mobile No additional expenditure is App involved. 11. Customs and Excise HK Car First $45,000 19 400 Department Registration Tax 12. Department of Health CookSmart: $35,000 49 000 (Central Health EatSmart Recipes Education Unit) 13. Department of Health EatSmart Restaurant $16,000 41 000 (Central Health Education Unit) 14. -

Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Finance Committee Report on the examination of the Estimates of Expenditure 2019-2020 July 2019 Finance Committee Report on the examination of the Estimates of Expenditure 2019-2020 July 2019 CONTENTS Chapter Page I Introduction 1 – 2 II Civil Service 3 – 10 III Administration of Justice and Legal Services 11 – 23 IV Central Administration and Other Services 24 – 37 V Financial Services 38 – 47 VI Public Finance 48 – 54 VII Constitutional and Mainland Affairs 55 – 63 VIII Environment 64 – 78 IX Housing 79 – 91 X Transport 92 – 105 XI Home Affairs 106 – 116 XII Commerce, Industry and Tourism 117 – 136 XIII Communications and Creative Industries 137 – 145 XIV Food Safety and Environmental Hygiene 146 – 159 XV Health 160 – 170 XVI Innovation and Technology 171 – 186 XVII Planning and Lands 187 – 205 XVIII Works 206 – 215 XIX Education 216 – 231 XX Security 232 – 246 XXI Welfare and Women 247 – 264 XXII Labour 265 – 276 Appendix Page I Programme of the special meetings of the Finance A1 – A3 Committee II Summary of written and supplementary questions B1 – B3 and requests for additional information III Attendance of members and public officers at the C1 – C37 special meetings of the Finance Committee IV Speaking notes of Directors of Bureaux, Secretary D1 – D98 for Justice, and Judiciary Administrator Chapter I : Introduction 1.1 At the Legislative Council meeting of 27 February 2019, the Financial Secretary of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government introduced the Appropriation Bill 2019. Following the adjournment of the Bill at Second Reading and in accordance with Rule 71(11) of the Rules of Procedure, the President of the Legislative Council referred the Estimates of Expenditure to the Finance Committee for detailed examination before the Bill was further proceeded with in the Council. -

Digital Culture in Hong Kong Canadian Communities: Literary Analysis of Yi Shu’S Fiction Jessica Tsui-Yan Li York University

Digital Culture in Hong Kong Canadian Communities: Literary Analysis of Yi Shu’s Fiction Jessica Tsui-yan Li York University Hong Kong Canadian Communities have particularly expanded between the 1980s 191 and the mid-1990s, in part owing to a new wave of Hong Kong immigration to Canada in recent years. This large-scale migration is mainly due to Hong Kong’s dynamic geopolitical and economic relationships with Mainland China and Canada as a result of its transformation from a British colony (1842-1997) to a postcolonial city. Hong Kong Canadian migration and communities offer important contribu- tions to the sociohistorical, political, and economic heterogeneity of multicultural Canadian communities. As a trading centre on Mainland China’s south coast, Hong Kong was an important stop on the travels of Chinese migrants to Canada from the late eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. With the hardworking ethics of its population and its role as a window to the rest of the world for Mainland China, Hong Kong gradually developed from a fishing port into an industrial city and then became an international financial centre, making the most of an economic uplift that began in the 1970s. With the advance of global capitalism, Hong Kong has progressively established its distinctive judicial, financial, medical, educational, transportation, and social welfare systems, and gradually produced a local culture and a sense of identity. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) play a significant role in shaping contemporary diasporic communities, such as those of Hong Kong Canadians. According to Leopoldina Fortunati, Raul Pertierra, and Jane Vincent, “The appropriation of the new media by migrants has changed the way in which today people migrate, move, negotiate their personal and national identity and make strategies to deal with new cultures. -

The Case of the Second Person Plural Form Memòria D’ Investigació

Pronominal variation in Southeast Asian Englishes: the case of the second person plural form Memòria d’ investigació Autora: Eva María Vives Centelles Directora: Cristina Suárez Gómez Departament de Filologia Espanyola, Moderna i Clàssica Universitat de les Illes Balears Data 10 Gener 2014 OUTLINE 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………...........2 2. Brief history of World Englishes ……………………………………............4 3. Theoretical framework: Models of analysis………………………………...6 3.1 Kachru’s Three Concentric Circles……………………………..7 3.2.McArthur’s Circle of World English…………………………..10 3.3.Görlach’s A circle of International English…………………….12 3.4.Schneider’s Dynamic Model of Postcolonial Englishes……….14 4. East and South-East Asian Englishes………………………………………25 4.1. Indian English (IndE) .…………………………………………26 4.2. Hong Kong English (HKE)…………………………………….34 4.3 Singapore English (SingE)……………………………………...38 4.4. The Philippines English (PhilE)………………………………44 5. Second person plural forms in the English language……………………....48 6. Description of the corpus and data analysis……………………………….58 6.1. Description of the corpus………………………………………58 6.2. Data Analysis…………………………………………………..61 7. Conclusions……………………………………………………...................80 8. Limitations of the study…………………………………………………….84 9. Questions for further research……………………………………………...84 10. References.....................................................................................................85 11. Appendix…………………………………………………………………...93 1 1. INTRODUCTION When the American president John Adams (1735-1826) -

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. These changes have affected the cost-benefit calculations of media ownership and led to the entrance of Chinese capital into the Hong Kong media scene. The digital media arena is also facing the challenge of intrusion by the state. KEYWORDS: press freedom, political economy, self-censorship, digital media, media business, Hong Kong. wo decades after the handover, many observers, academics, and jour- part follows past scholarship to outline the ownership structure of the Hong nalists would agree that press freedom in Hong Kong has declined over Kong media system, while noting how several counteracting forces have Ttime. The titles of the annual reports by the Hong Kong Journalists As- prevented the media from succumbing totally to political power.