Thomas Merton, Louis Massignon, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sufi Reading of Jesus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals... Representations of Jesus in Islamic Mysticism: Defining the „Sufi Jesus‟ Milad Milani Created from the wine of love, Only love remains when I die. (Rumi)1 I‟ve seen a world without a trace of death, All atoms here have Jesus‟ pure breath. (Rumi)2 Introduction This article examines the limits touched by one religious tradition (Islam) in its particular approach to an important symbolic structure within another religious tradition (Christianity), examining how such a relationship on the peripheries of both these faiths can be better apprehended. At the heart of this discourse is the thematic of love. Indeed, the Qur’an and other Islamic materials do not readily yield an explicit reference to love in the way that such a notion is found within Christianity and the figure of Jesus. This is not to say that „love‟ is altogether absent from Islamic religion, since every Qur‟anic chapter, except for the ninth (surat at-tawbah), is prefaced In the Name of God; the Merciful, the Most Kind (bismillahi r-rahmani r-rahim). Love (Arabic habb; Persian Ishq), however, becomes a foremost concern of Muslim mystics, who from the ninth century onward adopted the theme to convey their experience of longing for God. Sufi references to the theme of love starts with Rabia al-Adawiyya (717-801) and expand outward from there in a powerful tradition. Although not always synonymous with the figure of Jesus, this tradition does, in due course, find a distinct compatibility with him. -

Holy Land Itinerary December 16, 2008 - January 1, 2009

Holy Land Itinerary December 16, 2008 - January 1, 2009 December 16: Depart Houston IAH Delta Airlines, 5:55 p.m. via Atlanta to Tel Aviv. December 17: O Wisdom, O Holy Word of God, you govern all creation with your strong yet tender care. Come and show your people the way to salvation. Arrive Tel Aviv 5:25 p.m. Depart by motor coach for Haifa. Mass/Dinner/Accommodations at Carmelite Guest House – Stella Maris. December 18: O Adonai, who showed yourself to Moses in the burning bush, who gave him the holy law on Sinai mountain: come, stretch out your mighty hand to set us free. Mass in Church of the Prophet Elijah’s cave on Mt. Carmel. Depart for Nazareth via Acre, site of Crusader city and castle (Richard the Lion-Hearted) – lunch stop; to Sepphoris to visit an archeological dig of city where Joseph and Jesus may probably have worked (4 miles from Nazareth) to help build one of Herod’s great cities; to Nazareth. Dinner/Accommodations at Sisters of Nazareth Guest House adjacent to the Basilica of the Annunciation and over the probable site of the tomb of St. Joseph. December 19: O Flower of Jesse’s stem, you have been raised up as a sign for all peoples; kings stand silent in your presence; the nations bow down in worship before you. Come, let nothing keep you from coming to our aid. Mass in ancient Grotto of the Annunciation (home of Joachim and Ann); visit Mary’s well, Church of the Nutrition over home of Holy Family, International Marian Center. -

CGS Newsletter

Preparing for Easter at Home as a Family Listening to God with Children during Holy Week As a family, we can prepare spiritually and physically by listening to and reflecting upon the Word of God together with our children. Most interestingly, without the sacraments - the bread and wine - we contemplate on the Word of God, discovering more earnestly how God comes to be with us through the Word. To enter more deeply into Easter preparation, we transport ourselves to the historical place and time of the Paschal Mystery, before bringing our focus on the Holy Triduum. Biblical Geography: The Land of Israel City of Jerusalem. The children in the Material at Home. Find a physical map from a Atrium are initiated into the geography of biblical atlas or a virtual map of Israel online. Israel, focusing on its principal cities. During Lent, we deep-dive into the city of The Holy Land Model of Jerusalem (official site) Jerusalem and important places that tell or see a video overview here. This is a 1:50 us about Jesus' final days on earth with three-dimensional scale model of the city of His disciples. Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period. City of Jerusalem Map You may print this for the children to colour in and refer to while reading scripture. After looking at how the city was laid out, with its walls and its grand Temple, we then name and look more closely at the places where Jesus walked, giving children only a brief description. We focus on the location of: (1) the Cenacle, (2) the house of Caiaphas, (3) the Antonia Tower, (4) the Garden of Olives, (5) Calvary and (6) the tomb of the resurrection (RPC1, p. -

Islam in Europe

The Way, 41.2 (2001), 122-135. www.theway.org.uk 122 Islam in Europe Anthony O'Mahony SLAM PRESENTS TWO DISTINCT FACES to Europe, the one a threat, the I other that of an itinerant culture. However viewed, the history of the relationship between Islam and Europe is problematic and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. The relationship between Christians and Muslims over the centuries has been long and tortuous. Geographically the origins of the two communities are not so far apart - Bethlehem and Jerusalem are only some eight hundred miles from Mecca. But as the two communities have grown and become universal rather than local, the relationship between them has changed - sometimes downright enmity, sometimes rivalry and competition, sometimes co-operation and collaboration. Different regions of the world in different centuries have therefore witnessed a whole range of encounters between Christians and Muslims. The historical study of the relationship is still in its begin- nings. It cannot be otherwise, since Islamic history, as well as the history of those Christian communities that have been in contact with Islam, is still being written. Obviously Christian-Muslim relations do not exist in a vacuum. The two worlds have known violent confrontation: Muslim conquests of Christian parts of the world; the Crusades still vividly remembered today; the expansion of the Turkish Ottoman Empire; the Armenian massacres and genocide; European colonialism of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; the rise of Christian missions; the continuing difficult situations in which Christians find themselves in dominant Muslim societies, such as Sudan, Indonesia, Pakistan. -

Xbulletin-May 28 2017

First Communion Class of 2017 St. Bernadette Catholic Church St. Bernadette Catholic Church May 28, 2017 350 NW California Boulevard, Port St. Lucie, FL 34986 Page 2 Dear Friends, Where the Lord has gone, we hope to follow. These words summarize today’s Solemnity of the MONDAY, MAY 29, 2017 Ascension of the Lord into Heaven. 8:00 am †Jean Martino, requested by loving son, Ric As much as the Disciples witnessing the event (and we too, for that matter) naturally lift our TUESDAY, MAY 30, 2017 heads to try to catch a glimpse of the Lord as He 8:00 am †Lillian Tulumello, requested by disappears into the clouds, we must spend our Mary Ann & Warren Evensen lives preparing to ascend to our God as well. As WEDNESDAY, MAY 31, 2017 Matthew Leonard once said, we are either 8:00 am †Miriam Foppe, requested by spending our lives going up or going down. Bob & Family Prayer, Eucharistic Adoration, practicing the THURSDAY, JUNE 1, 2017 Corporal and Spiritual Works of Mercy, in other 8:00 am †Betty Hartley, requested by words, being good stewards of God’s gifts, help us Richard & Barbara Jaworski do what we can to be lifted up and follow the Lord Jesus into His Kingdom, into the arms of our FRIDAY, JUNE 2, 2017 Heavenly Father. 8:00 am †Deceased members of the Benedict Family, requested by May today’s Ascension further deepen our Suresh & Angeline Desai prayer for the Holy Spirit to come upon us, next SATURDAY, JUNE 3, 2017 week on Pentecost and every day of our lives! 8:00 am †Mario Aday, requested by Martha Gil Have a wonderful week! 4:00 pm †Henry & Jeanne Archambault, Father Victor Ulto, Pastor requested by Ken & Jeannine Anderson SUNDAY, JUNE 4, 2017 7:30 am †Mary & Martin Healy, requested by granddaughter, Kathy 9:00 am For the People of the Parish 10:45 am †Dionisio & Zoila Suarez, requested by their son Today, Sunday, May 28 is the last weekend for the 12:15 pm Mass. -

Pathways to an Inner Islam

Chapter One INTRODUCTION The spiritual, mystical, and esoteric doctrines and practices of Islam, which may be conveniently, if not quite satisfactorily, labeled as Sufi sm, have been among the main avenues of the understanding of this religion in Western aca- demic circles, and possibly among Western audiences in general. This stems from a number of reasons, not the least of which is a diff use sense that Sufi sm has provided irreplaceable keys for reaching the core of Muslim identity over the centuries, while providing the most adequate responses to contemporary disfi gurements of the Islamic tradition. It is in this context that we propose, in the current book, to show how the works of those whom Pierre Lory has called the “mystical ambassadors of Islam”1 may shed light on the oft-neglected availability of a profound and integral apprehension of Islam, thereby helping to dispel some problematic assumptions feeding many misconceptions of it. The four authors whom we propose to study have introduced Islam to the West through the perspective of the spiritual dimension that they themselves unveiled in the Islamic tradition. These authors were mystical “ambassadors” of Islam in the sense that their scholarly work was intimately connected to an inner call for the spiritual depth of Islam, the latter enabling them to intro- duce that religion to Western audiences in a fresh and substantive way. It may be helpful to add, in order to dispel any possible oversimplifi cations, that these authors should not be considered as representatives of Islam in the literal sense of one who has converted to that religion and become one of its spokesmen.2 None of these four “ambassadors” was in fact Muslim in the conventional, external, and exclusive sense of the word, even though two of them did attach themselves formally to the Islamic tradition in view of an affi liation to Sufi sm, in Arabic tasawwuf. -

An Introductory Comparative Study on the Role of Corbin and Izutsu in The

An Introductory Comparative Study on the Role of Corbin and Izutsu in the Philosophy of Contemporary ‘Iranian Islam’: Analyzing Its Motives and Resources from Heidegger to Massignon Ehsan SHARIATI Henry Corbin was among those spiritual philosophers of the contemporary world who deserve novel and serious investigations, particularly in the realm of comparative1 philosophy (and mysticism) with a phenomenological-hermeneutic vein serving as a connective bridge between the contemporary western philosophy (in the continental Europe) and the oriental philosophy (in Iran and in the Islamic world- and in particular, Shiism). This French philosopher was on the one hand, an expert in German philosophical language and translated for the first time two works by Martin Heidegger into French, while on the other hand, and at the same time, as a pupil of the eminent historian of the Middle Ages, Etienne Gilson, and of the protestant theologian, Jean Baruzi, and eventually under the guidance of Louis Massignon (as of 1928 onwards), turned to the spiritual philosophy, mysticism and Sufism in the Islamic World and the Shiism. After an initial fascination with Ibn Arabi, he particularly undertook a re-reading of the works of Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi (m. 1191 AC) and his Hikmat Al-Ishraq (Theosophia Matutina or the Oriental Theosophy). He later set out to systematically introduce worldwide other- less known- Iranian Shiite theosophers such as Mirdamad, as well as Mulla 31 Towards a Philosophy of Co-existence: A Dialog with Iran-Islam(2) Towards a Philosophy of Co-existence: A Dialog with Iran-Islam(2) Sadra and his Hikmat Motaalyiah (the Supreme Theosophy). -

A Different Location for the Cenacle by Roberto Raciti

A Different Location for the Cenacle by Roberto Raciti While reading Blessed Emmerich’s description of the Last Supper and the Cenacle, I realized that the true location of this place was somehow different from what is today generally accepted. This is not the only place which might be wrongly located, as I believe there are others, such as the true location of Mount Sinai. I compared the information contained in the book “The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ”, as the main source, as well as the Gospels. I also found what I believe to be the first mention of the House of the Last Supper in the Old Testament. First, let’s have a look at a map of ancient Jerusalem: I indicated the widely accepted location of the Cenacle in red, and Emmerich’s location in blue. As you can see, the new proposed location is located inside what once used to be David’s citadel on Mount Zion; this is much closer to the valley of Josaphat, and the Mount of Olives. This is what Emmerich tells us about the Cenacle: “The disciples had already asked Jesus where he would eat the Pasch. Today, before dawn, our Lord sent for Peter, James, and John, spoke to them at some length concerning all they had to prepare and order at Jerusalem and told them that when ascending Mount Sion, they would meet the man carrying a pitcher of water.” First, we must establish what Blessed Emmerich means by “Mount Sion”. Jerusalem has at least three prominent mounts, one is the Temple Mount, sometimes also called Mount Moriah or Araunah’s threshing floor. -

The Jesus Caritas Fraternities in the United States: the Early History 1963 – 1973

PO BOX 763 • Franklin Park, IL 60131 • [P] 260-786-JESU (5378) Website: www.JesusCaritasUSA.org • [E] [email protected] THE JESUS CARITAS FRATERNITIES IN THE UNITED STATES: THE EARLY HISTORY 1963 – 1973 by Father Juan Romero INTRODUCTION At the national retreat for members of the Jesus Caritas Fraternity of priests, held at St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo, California in July 2010, Father Jerry Devore of Bridgeport, Connecticut asked me, in the name of the National Council, to write an early history of Jesus Caritas in the United States. (For that retreat, almost fifty priests from all over the United States had gathered for a week within the Month of Nazareth, in which a smaller number of priests were participating for the full month.) This mini-history is to complement A New Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Msgr. Bryan Karvelis of Brooklyn, New York (RIP), and the American Experience of Jesus Caritas Fraternities by Father Dan Danielson of Oakland, California. It proposes to record the beginnings of the Jesus Caritas Fraternities in the USA over its first decade of existence from 1963 to 1973, and it will mark the fifth anniversary of the beatification of the one who inspired them, Little Brother Blessed Charles de Foucault. It purports to be an “acts of the apostles” of some of the Jesus Caritas Fraternity prophets and apostles in the USA, a collective living memory of this little- known dynamic dimension of the Church in the United States. It is not an evaluation of the Fraternity, much less a road map for its future growth and development. -

Saints and Blessed People

Saints and Blessed People Catalog Number Title Author B Augustine Tolton Father Tolton : From Slave to Priest Hemesath, Caroline B Barat K559 Madeleine Sophie Barat : A Life Kilroy, Phil B Barbarigo, Cardinal Mark Ant Cardinal Mark Anthony Barbarigo Rocca, Mafaldina B Benedict XVI, Pope Pope Benedict XVI , A Biography Allen, John B Benedict XVI, Pope My Brother the Pope Ratzinger, Georg B Brown It is I Who Have Chosen You Brown, Judie B Brown Not My Will But Thine : An Autobiography Brown, Judie B Buckley Nearer, My God : An Autobiography of Faith Buckley Jr., William F. B Calloway C163 No Turning Back, A Witness to Mercy Calloway, Donald B Casey O233 Story of Solanus Casey Odell, Catherine B Chesterton G. K. C5258 G. K. Chesterton : Orthodoxy Chesterton, G. K. B Connelly W122 Case of Cornelia Connelly, The Wadham, Juliana B Cony M3373 Under Angel's Wings Maria Antonia, Sr. B Cooke G8744 Cooke, Terence Cardinal : Thy Will Be Done Groeschel, Benedict & Weber, B Day C6938 Dorothy Day : A Radical Devotion Coles, Robert B Day D2736 Long Loneliness, The Day, Dorothy B de Foucauld A6297 Charles de Foucauld (Charles of Jesus) Antier, Jean‐Jacques B de Oliveira M4297 Crusader of the 20th Century, The : Plinio Correa de Oliveira Mattei, Riberto B Doherty Tumbleweed : A Biography Doherty, Eddie B Dolores Hart Ear of the Heart :An Actress' Journey from Hollywood to Holy Hart, Mother Dolores B Fr. Peter Rookey P Father Peter Rookey : Man of Miracles Parsons, Heather B Fr.Peyton A756 Man of Faith, A : Fr. Patrick Peyton Arnold, Jeanne Gosselin B Francis F7938 Francis : Family Man Suffers Passion of Jesus Fox, Fr. -

Mystics and Sufi Masters: Thomas Merton and Sufism

Mystics and Sufi Masters: Thomas Merton and Sufism; Merton and the Christian Dialogue with Islam (Sidney Griffith, Catholic University of America. Posted on this Home Page with author’s permission NB: since this is a scanned version, pardon any errors) I Christians and the Call to Islam Muslims and Christians have been in conversation with one another from the very beginnings of Islam as proclaimed in the Qur*an, and as preached by Muhammad in Mecca and Medina in the seventh century of the Christian era. Even a cursory glance through the Qur*an reveals that the holy book of Islam presumes in its readers a familiarity with the Torah and the Gospel, and with the sories of Adam, Noah, Joseph, Abraham, Moses, Mary, and Jesus of Nazareth. The Qur*an also readily reveals its intention to offer a critique of the religious beliefs and practices of Christians, and to offer a program for their correction. The most comprehensive verse addressed directly to Christians in this vein says: O People of the Book, do not exaggerate in your religion, and do not say about God anything but the truth. The Messiah, Jesus, Mary*s son, is only God*s messenger, and His Word He imparted to Mary, and a Spirit from Him. Believe in God and in His messengers, and do not say, ‘Three*. Stop it! It is better for you. God is but a single God; He is too exalted for anything to become a son to Him, anything in the heavens or anything on the earth. God suffices as a guardian. -

I Worry Until Midnight and from Then on I Let God Worry

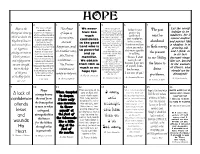

HOPE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The virtue of hope Hope is the The object We never The virtue of Let the world responds to the hope is so pleasing Today in your The past aspiration to happiness have too indulge in its theological virtue by of hope is, to God that He prayer you which God has placed in much has declared that confirmed must be madness, for it which we desire the the heart of every man; He feels delight in cannot endure it takes up the hopes in one way, confidence those who trust your resolution kingdom of heaven that inspire men's in Him: “The Lord to be a saint. abandoned and passes like eternal in the good taketh pleasure in activities and purifies I understand you a shadow. It is and eternal life as Lord who is them that hope them so as to order them happiness, and, in His Mercy” when you make to God's mercy, growing old, our happiness, to the Kingdom of so powerful (Ps. 46:11). this more specific heaven; it keeps man in another way, And He promises and I think, is placing our trust in from discouragement; and so victory over his by adding, the present in its last Christ's promises it sustains him during the Divine merciful. enemies, “I know I shall times of abandonment; perseverance in to our fidelity, decrepit stage. grace, and succeed, not and relying not on it opens up his heart in assistance . We obtain eternal glory to But we, buried expectation of eternal from Him as the man who because I am sure the future to in the wounds our own strength, beatitude.