Gladys Pratt Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 3 Article 4 7-1-1982 Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico F. LaMond Tullis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Tullis, F. LaMond (1982) "Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 22 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol22/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Tullis: Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico early mormon exploration and missionary activities in mexico F lamond tullis in 1875 a few days before the first missionaries to mexico were to depart brigham young changed his mind rather than have them travel to california where they would take a steamer down the coast and then go by foot or horseback inland to mexico city brigham asked if they would mind making the trip by horseback going neither to california nor mexico city but through arizona to the northern mexican state of sonora a round trip of 3000 miles he instructed them to look along the way for places to settle and to deter- mine whether the lamanitesLamanites were ready to receive the gospel but brigham young had other things in mind the saints might need another place of refuge and advanced -

56405988.Pdf (581.6Kb)

De Siste Dagers Hellige, Mitt Romney, og Den amerikanske religion av Kristian A. Kvalvåg Masteroppgave i religionsvitenskap Institutt for arkeologi, historie, kultur og religionsvitenskap Det humanistiske fakultet Universitetet i Bergen Våren 2009 2 3 Takk til alle som har har hjulpet meg med dette arbeidet, spesielt mine to veiledere, Dag Øystein Endsjø og Håkan Rydving. Jeg vil også rette en stor takk til min familie, som har støttet meg både moralsk og økonomisk, men også gitt meg en hand med å lese teksten og bearbeide dens språk, deriblant John Kvalvåg, Barbara Jean Bach Berntsen og Marius Berntsen. I extend my deep gratitude towards the friendly and forthcoming members of Northborough Ward of the Boston Stake, Massachusetts, and also the missionaries I had the opportunity to talk with, and especially my uncle and aunt David and Ann Bach for letting me stay with them for two months, eating their food, driving their white Cadillacs, attending church with them, getting to know the works of Bruce R. McConkie and James E. Talmage and presenting to me The Book of Mormon in both English and Norwegian, and not least being given the opportunity to attend a large number of political meetings and visiting Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Neither should I forget to mention Buster the Cat – Thanks for warming my lap all those hours! Må også takke Friedrich Nietzsche, Erich von Däniken og Fjodor Dostojevski for evig inspirasjon. Kristian A. Kvalvåg Bergen, mai 2009. 4 Innholdsfortegnelse Introduksjon : Å konstruere en sosial meningshorisont: No man knows Mitt ’s history........................ 7 Civil Religion................................................................................................................ 13 Kapittel 1 : Jesu Kristi Kirke av Siste Dagers Hellige ................................................................... -

Cardon History

CA:RDCN HISTORY ·. (facts ~athered fro~ letters, pedigree'eheets, family group.sheets, memory of the older~bers of, the family, and from Genealogical re search in America, France, w~d Italy. Writ1m ~ E"d.itlt t·arao·n 'T'hatc)ler.) The Gerd.on line§. are many and illustrious. We find tb.em in S:p~in, Fr~ce, Itatf, England, Belgium, and Switzerland. - .... l?l'oo·aoly the· ~gjliest record."we 'have "of Cardoiis is found. 'in the • "Nobiliare Universal de France 11 page 174.: v \'Spanish) CarQon ~- or Cardonn~ (de) de Sandrans were a very ancient family ><hose name originates from ~he'city of Cerdo~~e in Spain. T~is is a bout forty miles northwest of Barcelona, and is a city which has the 11 ti t1e of a "duchy •. · · The Lords de Cardonne were originally:named Felch, Mayor de Card~ o~~a. and Arragon, and contracts[ alliances with the Royal house of Aragon, and with the principal families of Europe; but the principal heritage was left iil. the families' of d'Axragon, de Beaumont, and de Monte-Mayor. is famil 'is so illustr~ous and ~~cient that we find proof of its members ong before the year 40. It was divided into many branches that spread in many parts of the continent and Europe. Raymnd Felch, Yiscomte ·de Cerdo~.na, having a· son died before 1:334. (Dutch, E!tglish Flemish, and. Irish). , IA 1387 A.D. ~ing Richard II invited a colony of Flemish linen wea vers to London, and also a,band. of silk weavers_. -

Ancestry of George W. Bush Compiled by William Addams Reitwiesner

Ancestry of George W. Bush (b. 1946) Page 1 of 150 Ancestry of George W. Bush compiled by William Addams Reitwiesner The following material on the immediate ancestry of George W. Bush was initially compiled from two sources: The ancestry of his father, President George Bush, as printed in Gary Boyd Roberts, Ancestors of American Presidents, First Authoritative Edition [Santa Clarita, Cal.: Boyer, 1995], pp. 121-130. The ancestry of his mother, Barbara Bush, based on the unpublished work of Michael E. Pollock, [email protected]. The contribution of the undersigned consists mostly in collating and renumbering the material cited above, adding considerable information from the decennial censuses and elsewhere, and HTML-izing the results. The relationships to other persons (see the NOTES section below) are intended to be illustrative rather than exhaustive, and are taken mostly from Mr. Roberts' Notable Kin and Ancestors of American Presidents books, with extensions, where appropriate, from John Young's American Reference Genealogy and from my own, generally unpublished, research. This page can be found at two places on the World Wide Web, first at http://hometown.aol.com/wreitwiesn/candidates2000/bush.html and again at http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~addams/presidential/bush.html. The first site will be updated first and more frequently, while the second site will be more stable. William Addams Reitwiesner [email protected] Ancestry of George W. Bush George Walker Bush, b. New Haven, Conn., 6 July 1946, Governor of Texas from 1994 to 2000, U.S. President from 2001 1 m. Glass Memorial Chapel, First United Memorial Church, Midland, Texas, 5 Nov. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005

Journal of Mormon History Volume 31 Issue 3 Article 1 2005 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 31 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol31/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES • --The Case for Sidney Rigdon as Author of the Lectures on Faith Noel B. Reynolds, 1 • --Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications Ugo A. Perego, Natalie M. Myres, and Scott R. Woodward, 42 • --Lucy's Image: A Recently Discovered Photograph of Lucy Mack Smith Ronald E. Romig and Lachlan Mackay, 61 • --Eyes on "the Whole European World": Mormon Observers of the 1848 Revolutions Craig Livingston, 78 • --Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons Stephen C. LeSueur, 113 • --Artois Hamilton: A Good Man in Carthage? Susan Easton Black, 145 • --One Masterpiece, Four Masters: Reconsidering the Authorship of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Nathan D. Grow, 170 • --The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism Ronald W. Walker, 198 • --Kerstina Nilsdotter: A Story of the Swedish Saints Leslie Albrecht Huber, 241 REVIEWS --John Sillito, ed., History's Apprentice: The Diaries of B. -

A Matter of Faith: a Study of the Muddy Mission

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1997 A matter of faith: A study of the Muddy Mission Monique Elaine Kimball University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Kimball, Monique Elaine, "A matter of faith: A study of the Muddy Mission" (1997). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/e6xy-ki9b This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any typo ol computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

July 20Th, Elder Ballard, Elder Salt Lake City

15 7 number ISSUE 167 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS Pioneer Month is here! My wife Kathy President’s Message . 1 Membership Report . .. 2 and I serve in a church branch of women Encampment Registration . 3 recovering from meth and heroine National News . 5 addictions. This morning we took them Announcements . .6 Pioneer Stories . 9 all to Temple Square to hear “The National Calendar . 11 Spoken Word.” As we listened to the Chapter News . 12 patriotic music sung by the Tabernacle Boulder Dam . 12 Choir we were filled with gratitude for Box Elder . .. 13 Centerville . 14 the sacrifices of our forefathers. What a Cotton Mission . 14 wonderful way to kick off my favorite Jordan River Temple . 15 month that celebrates our marvelous Lehi . 16 Mills . 17 country, and our incredible state! Morgan . 18 Recently the Executive Board got a sneak peek of the new Porter Rockwell . 21 monuments being installed at ‘This is the Place’ Park. At our Portneuf . 21 Red Rocks . 22 SUPer DUPer day on Saturday, July 20th, Elder Ballard, Elder Salt Lake City . 22 Holland, the Governor and others will be attending the 30 minute Settlement . 23 Dedication honoring the children who died crossing the plains. Your Sevier . 24 Taylorsville . 25 grandchildren will never forget this once in a lifetime event. You can Temple Fork . .. 25 get early discounted tickets through This is the Place directly. (Click Temple Quarry . .. 26 here for details) Timpanogos . .. 26 Upper Snake River Valley . 27 Upcoming Events . 28-31 Legacy Society . 32 Do Something Monumental . 34 IRA Charitable . 35 Chapter Excellence . -

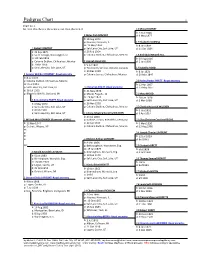

Pedigree Chart 1 Chart No

Pedigree Chart 1 Chart no. 1 No. 1 on this chart is the same as no. 0 on chart no. 0 16 Miles ROMNEY b: 13 Jul 1806 8 Miles Park ROMNEY d: 3 May 1877 b: 18 Aug 1843 p: Nauvoo, Hancock, IL 17 Elizabeth GASKELL m: 10 May 1862 b: 8 Jan 1809 4 Gaskell ROMNEY p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT d: 11 Oct 1884 b: 22 Sep 1871 d: 26 Feb 1904 p: Saint George, Washington, UT p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 18 Archibald Newell HILL m: 20 Feb 1895 b: 20 Aug 1816 p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 9 Hannah Hood HILL d: 2 Jan 1900 d: 7 Mar 1955 b: 9 Jul 1842 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT p: Tosoronto, Simcoe, Ontario, Canada 19 Isabella HOOD d: 29 Dec 1928 b: 8 Jul 1821 2 George Wilcken ROMNEY -Royal ancestry p: Colonia Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico d: 20 Mar 1847 b: 8 Jul 1907 p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 20 Parley Parker PRATT - Royal ancestry m: 2 Jul 1931 b: 12 Apr 1807 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT 10 Helaman PRATT -Royal ancestry d: 13 May 1857 d: 26 Jul 1995 b: 31 May 1846 p: Bloomfield Hills, Oakland, MI p: Mount Pisgah, , IA 21 Mary WOOD m: 20 Apr 1874 b: 18 Jun 1818 5 Anna Amelia PRATT -Royal ancestry p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT d: 5 Mar 1898 b: 6 May 1876 d: 26 Nov 1909 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico 22 Charles Heinrich WILCKEN d: 4 Feb 1926 b: 5 Oct 1831 p: Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT 11 Anna Johanna Dorothy WILCKEN d: 9 Apr 1914 b: 25 Jul 1854 1 Willard Mitt ROMNEY (Governor of MA) p: Dahme, Zarpin, Rheinfeld, Germany 23 Eliza Christina Carolina REICHE b: 12 Mar 1947 d: 22 Jun 1929 b: 1 May 1830 p: Detroit, Wayne, MI p: Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, Mexico d: 13 Aug 1906 m: p: 24 Joseph Charles LAFOUNT d: b: 12 Jul 1829 p: 12 Robert Arthur LAFOUNT d: bef 1861 b: 9 Mar 1856 sp: p: Belbroughton, Worcester, Eng. -

The Juarez Stake Academy

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1955 The Juarez Stake Academy Dale M. Valentine Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Educational Sociology Commons, History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Valentine, Dale M., "The Juarez Stake Academy" (1955). Theses and Dissertations. 5183. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5183 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE JUAREZ STAKE ACADEMY A Thesis Submitted to the Division of Religion Brigham Young University Provo, Utah In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts 199043 by Dale M. Valentine June 1955 iii PREFACE The first inducements to investigate or study the Juarez Stake Academy were received by the author as a result of contact with alumni of that institution. Through associations with and awareness of its alumni it has become apparent to the author that the Juarez Stake Academy has produced graduates of extremely high caliber and character who have been successful in most vocational, academic, and administrative fields. This achievement seems to be far above and out of proportion to the size of the Academy. Such a realization would, quite naturally, invoke an attitude of inquiry to determine what are the underlying causes of such an effect. It is the author!s belief that many of the answers can be found through an objective examination of historical and other factual information dealing with the Juarez Stake Academy. -

Importation of Arms and the 1912 Mormon "Exodus" from Mexico

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 72 Number 4 Article 3 10-1-1997 Importation of Arms and the 1912 Mormon "Exodus" from Mexico B. Carmon Hardy Melody Seymour Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Hardy, B. Carmon and Melody Seymour. "Importation of Arms and the 1912 Mormon "Exodus" from Mexico." New Mexico Historical Review 72, 4 (1997). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol72/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Importation of Arms and the 1912 Mormon "Exodus" from Mexico B. CARMON HARDY and MELODY SEYMOUR In the hot, dry days of late July and early August 1912, thousands of North Americans raced north across the border into the United States at El Paso, Texas and Hachita, New Mexico. Due to revolutionary vio lence in Mexico, refugees had filtered north for months. This latest, unexpected wave was by far the largest. It consisted mostly of polyga mous families from Mormon colonies in Chihuahua and Sonora. Crowded into makeshift facilities at the EI. Paso lumber yard and a quickly constructed tent city at Hachita, their presence soon became the object of curious journalists. Many outside the area became aware for the first time that Mormons, or Latter~day Saints, lived south ofthe United States-Mexican border and had resided there for a generation.' The earliest arrivals consisted chiefly of women and children shepherded by male guardians. -

La Misión Del Apóstol Moses Thatcher a La Ciudad De México En 18791

17 de octubre de 1012 La misión del apóstol Moses Thatcher a la Ciudad de México en 18791 Por LaMond Tullis Desde los comienzos de la Restauración, los líderes de la Iglesia se esforzaron por compartir el Evangelio restaurado en todos los lugares que podían, estos esfuerzos incluían misiones entre los lamanitas, a quienes consideraban que en su mayoría eran los nativos de América, los pueblos mestizos en el hemisferio occidental y los polinesios del pacífico. Cualquiera que haya sido la amplia mezcla interétnica que se extendió por más de cien generaciones, los primeros líderes consideraban que de algún modo estas personas eran descendientes de la familia de Lehi quienes hicieron un viaje extraordinario desde la Península Arábiga hasta las Américas huyendo de Jeru- salén en el año 600 A.C.2 Existen otros dos viajes transoceánicos narrados en el Libro de Mor- món, el primero desde Mesopotamia y el segundo también desde Jerusalén que sin duda dejaron sus propias generaciones.3 Inclusive durante las guerras de exterminio en el siglo IV d.C., en las que mataron a un gran número de los descendientes de Lehi, el impresionante cronista y profeta Mormón afirmó que Dios no abandonaría para siempre al “remanente de la casa de Israel”, y tenía en mente a los lamanitas que para ese entonces eran una mezcla de varios grupos étnicos, incluyendo a los asus- tados y apóstatas nefitas cuya valentía les había fallado en la estela de la vida errante y el salva- jismo interétnico. En los últimos días Dios los favorecería con bendiciones que una vez más los llevarían al conocimiento de su Salvador y los pondría en una posición prominente en Su reino, de hecho, “los lamanitas florecerían como la rosa” (D y C 49:24). -

A Guide to Mormon Manuscripts at the Huntington Library

HUNTINGTON LIBRARY, ART COLLECTIONS & BOTANICAL GARDENS LIBRARY DIVISION — MANUSCRIPTS DEPARTMENT 1151 OXFORD ROAD SA N MARINO, CA 91108 “A Firm Testimony of the Truth” : A Guide to Mormon Manuscripts at the Huntington Library Katrina C. Denman L i b rary Assistant, Western Historical Manuscripts The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens 2012; revised 2014 & 2015 No reproduction, quotation or citation without the written permission of the Huntington Library and the author is permitted. A GUIDE TO MORMON MANUSCRIPTS AT THE HUNTINGTON LIBRARY 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 OVERVIEW OF MORMON MANUSCRIPTS 5 CALL NUMBERS & ABBREVIATIONS USED 6 MORMON FILE INDIVIDUAL MANUSCRIPTS 6 Container list of individual manuscripts – including letters, diaries, autobiographies, and genealogies – in the 16 boxes of the Mormon File. INDIVIDUALLY BOUND & BOXED MANUSCRIPTS 17 Individually bound or boxed diaries, autobiographies, biographies, and other manuscripts. INDIVIDUAL MANUSCRIPTS IN NON-MORMON COLLECTIONS 19 MICROFILM 21 Digitized and available for viewing online at the Huntington Digital Library. BOUND PHOTOSTATIC FACSIMILES 28 Bound facsimiles of diaries, autobiographies, and record books. SMALL COLLECTIONS 30 Mormon collections consisting of 40 or fewer items. COLLECTIONS 31 Mormon collections consisting of 40 or more items, as well as non-Mormon specific collections with a substantial amount of Mormon-related material. CONCLUSION 38 OTHER MORMON RESOURCES & ACCESSING THE COLLECTIONS 39 QUICK GUIDE TO MORMON RESOURCES AT THE HUNTINGTON 41 Cover Image: Portrait of Joseph Smith from Tullidge’s Quarterly Magazine, Vol.1., No.1., October 1880. Rare Books 191739. Title quote from Martha Cox, Autobiographical sketch, 1928. FAC 561. A GUIDE TO MORMON MANUSCRIPTS AT THE HUNTINGTON LIBRARY 3 INTRODUCTION Since its establishment in 1919, the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens has achieved international renown for the magnificence of its gardens and of its public exhibits.