Southeast Asian Comic Artists Invade USA!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

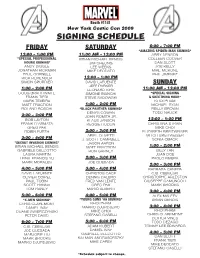

Signing Schedule

Booth #1141 New York Comic Con 2009 SIGNING SCHEDULE FRIDAY SATURDAY 6:00 – 7:00 PM *AMAZING SPIDER-MAN SIGNING* 12:00 – 1:00 PM 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM ABBY DENSON *SPECIAL PROFESSIONAL BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS COLLEEN COOVER HOURS SIGNING* JIM CHEUNG DAN SLOTT ANDY DIGGLE LEE WEEKS JOE KELLY JONATHAN HICKMAN MIKE DEODATO MIKE MCKONE PAUL CORNELL PHIL JIMENEZ RICK REMENDER 12:00 – 1:00 PM SIMON SPURRIER DAVID LAFUENTE SUNDAY JEFF PARKER 1:00 – 2:00 PM LEONARD KIRK 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM DOUG BRAITHWAITE SIMONE BIANCHI *SPECIAL SIGNING FRANK TIERI STEVE SADOWSKI & SKECTHING HOUR* MARK TEXEIRA KHOI PHAM MATT FRACTION 1:00 – 2:00 PM MICHAEL RYAN ROLAND BOSCHI *BLACK PANTHER SIGNING* REILLY BROWN DENYS COWAN TODD NAUCK 2:00 – 3:00 PM JOHN ROMITA JR. BOB LAYTON KLAUS JANSON 12:00 – 1:00 PM FRANK D’ARMATA REGGIE HUDLIN CHRISTINA STRAIN GREG PAK MIKE CHOI ROBIN FURTH 2:00 – 3:00 PM ELIZABETH BREITWEISER ARIEL OLIVETTI MITCH BREITWEISER 3:00 – 4:00 PM J. SCOTT CAMPBELL SONIA OBACK *SECRET INVASION SIGNING* JASON AARON BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS MATT FRACTION 1:00 – 2:00 PM GABRIELE DELL’OTTO RON GARNEY BILLY TAN LAURA MARTIN JUAN DOE LEINIL FRANCIS YU 2:00 – 3:00 PM PAOLO RIVERA MARK MORALES JOE QUESADA 2:00 – 3:00 PM 4:00 – 5:00 PM 3:00 – 4:00 PM BARBARA CANEPA DAVID LAFUENTE CHRISTOS GAGE C.B. CEBULSKI OLIVIER COIPEL DENNIS CALERO CHRISTOPHE ARLESTON PAUL TOBIN FRED VAN LENTE GIUSEPPE CAMUNCOLI SCOTT HANNA GREG PAK MARK BROOKS TOM RANEY MARIO ALBERTI 3:00 – 4:00 PM 5:00 – 6:00 PM 4:00 – 5:00 PM ALEX MALEEV *X-MEN SIGNING* *YOUNG GUNS ’09 SIGNING* BRIAN BENDIS CHRIS CLAREMONT KHOI PHAM DANIEL WAY MARKO DJURDJEVIC 3:00 – 4:00 PM DUANE SWIERCZYNSKI MIKE CHOI KHOI PHAM PETER DAVID STEFANO CASELLI CHRIS CLAREMONT DEXTER VINES 6:00 – 7:00 PM 5:00 – 6:00 PM TODD DEZAGO C.B. -

![1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4211/1-over-50-years-of-american-comic-books-hardcover-1904211.webp)

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover] Product details Publisher: Bdd Promotional Book Co Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0792454502 Publication Date: November 1, 1991 A half-century of comic book excitement, color, and fun. The full story of America's liveliest, art form, featuring hundreds of fabulous full-color illustrations. Rare covers, complete pages, panel enlargement The earliest comic books The great superheroes: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and many others "Funny animal" comics Romance, western, jungle and teen comics Those infamous horror and crime comics of the 1950s The great superhero revival of the 1960s New directions, new sophistication in the 1970s, '80s and '90s Inside stories of key Artist, writers, and publishers Chronicles the legendary super heroes, monsters, and caricatures that have told the story of America over the years and the ups and downs of the industry that gave birth to them. This book provides a good general history that is easy to read with lots of colorful pictures. Now, since it was published in 1990, it is a bit dated, but it is still a great overview and history of comic books. Very good condition, dustjacket has a damage on the upper right side. Top and side of the book are discolored. Content completely new 2. Alias the Cat! Product details Publisher: Pantheon Books, New York Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0-375-42431-1 Publication Dates: 2007 Followers of premier underground comics creator Deitch's long career know how hopeless it's been for him to expunge Waldo, the evil blue cat that only he and other deranged characters can see, from his cartooning and his life. -

New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (V

New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (v. 8, Bk. 1) by Brian Michael Bendis ebook Ebook New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (v. 8, Bk. 1) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (v. 8, Bk. 1) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 120 pages+++Publisher:::: Marvel (December 10, 2008)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0785129464+++ISBN-13:::: 978- 0785129462+++Product Dimensions::::1 x 1 x 1 inches++++++ ISBN10 0785129464 ISBN13 978-0785129 Download here >> Description: The Skrulls, shape-shifting aliens led by their queen Veranke, have invaded the planet with information they learned from the Illuminati and, after surviving the House of M, Spider-Woman, the Hood, and the other Avengers fight back to save Earth. Collects The New Avengers (2005) # 38-425 single-issue stories related to Secret Invasion. Each issue is by a different artist, but theyre all good, so thats alright. The New Avengers and Mighty Avengers tie-in books were better than the main event book.38 Art by Michael G. - Luke Cage is not happy about Jessica Jones decision to go to Starks Tower.39 Art bt David Mack - Echo and Wolverine fight a Skrull with multiple superpowers.40 Pencils by Jim Cheung - What the Skrulls have been up to the past several years. Background on their queen. She decides to be part of the infiltration as a replacement for an Avenger.41 Art by Billy Tan - Ka-Zar and Shanna fight Skrulls in the Savage Land.42 Pencils by Jim Cheung - Continues the story of the Skrull queen in her new guise on Earth. -

Read Book Uncanny X-Force by Rick Remender

UNCANNY X-FORCE BY RICK REMENDER: THE COMPLETE COLLECTION VOLUME 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rick Remender | 520 pages | 19 Aug 2014 | Marvel Comics | 9780785188230 | English | New York, United States Uncanny X-force By Rick Remender: The Complete Collection Volume 1 PDF Book Leonardo Manco Illustrations ,. See X-Statix, below, for the Omnibus that collects these issues and a description of the run. Yay Congrats on season 5! Upon X-Force's return to the present, they capture Mystique and argue over whether or not to kill Evan. A must buy. Conn — Thanks so much for the catch! Other than that, I feel like Wolverine is the only character that doesn't really shine through in this book. List vol. Jan 18, Eric rated it really liked it. Lastly we have Mark Brooks. I had also had some ideas of what I had heard so many good things about Remender's "Uncanny X-Force" and having read some of his other works and enjoying them, I was looking forward to reading this collection when I found it at the library. Amazon Music Stream millions of songs. More From Various. Co-stars Dr. Remender obviously knows these characters well. Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. The team faces The Final Horsemen and suffers pestilence and plagues in graphic detail: boils and pustules rupture while Wolverine is nearly cleaved in half by an axe-wielding avatar of War. I will definitely be picking up volume 2 of this really soon. A heavy reliance on past events, clunky pacing, and questionable ret-cons were some of the lows. -

El PDF Con Todas Las Imágenes

paninicomics PEPE Decir que José González era dibujante de cómics e ilustrador es quedarse corto, muy corto. José González, Pepe, era una fuerza de la naturaleza capaz de hacer cualquier cosa que se propusiera y hacerla bien. Admirado por su arte en todo el mundo, su peculiar forma de enfrentarse a la vida hizo que su entorno no siempre le entendiera bien. Pocas personalidades del mundo del cómic han sido tan influyentes como Pepe. Carlos Giménez, que le conoció muy bien, se atreve, siguiendo un poco la senda abierta en Los Profesionales, a realizar la biografía de Pepe. En cinco entregas, Giménez nos ofrecerá su obra cumbre en la que su arte y, sobre todo, su capacidad de análisis del alma humana, nos ofrece un impresionante fresco de quién fue José González, Pepe. En esta primera entrega veremos retazos de la infancia de Pepe y cómo entró en el mundo del cómic de la mano de Josep Toutain. Guión y dibujo de Carlos Gimenez Libro en tapa dura. 96 páginas. 15 € CUBIERTA PROVISIONAL CUBIERTA SUPERIOR Contiene Superior 1-6 USA ¡La nueva genialidad del guionista de Civil War, Kick-Ass y Némesis! Simon Pooni lo tenía todo: buenos amigos, chicas que querían salir con él y un prometedor futuro como jugador de béisbol... Pero todo eso cambió cuando le diagnosticaron esclerosis múltiple. Ahora, sólo se siente feliz cuando está leyendo sus cómics y contemplando sus películas. Y es entonces cuando... Superior entra en su vida y todo cambiará para siempre. Guión de Mark Millar Dibujo de Leinil Francis Yu Libro en tapa dura. -

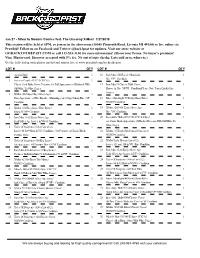

Or Live Online Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

Jan 27 - Silver to Modern Comics feat. The Uncanny X-Men! 1/27/2018 This session will be held at 6PM, so join us in the showroom (35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) or live online via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! (Showroom Terms: No buyer's premium! Visa, Mastercard, Discover accepted with 5% fee. No out of state checks. Lots sold as-is, where-is.) Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Info 1 16 Iron Man #10/Classic Mandarin. 1 Nice F/F+ Condition. 2 Forever People #1/1971 CGC 6.5. 1 Classic Jack Kirby Cover. Features 1st Full Appearance of Darkseid With 17 Iron Man #9/Classic Hulk Cover. 1 Off-White To White Pages. Shows As Nice VF/VF+ Condition Please Note Paper Quality Has Tanned. 3 X-Men #28/Super Key Silver Age! 1 First Appearance of The Banshee! Humdinger of a Copy! Sharp Fine+/VF 18 Marvel Spotlight #7/Early Ghost Rider. 1 Condition. VG/VG+ Condition. 4 X-Men #108/Key Issue/First Byrne! 1 19 X-Men #26/1966 Early Silver Age. 1 Sharp VF/VF+ Condition. Nice VG+ Condition. 5 Iron Man 11-12/Early Silver Age. 1 20 Incredible Hulk #271/1982 CGC 6.5 Key! 1 Early Silver Age Issues in VG+/F Condition. 1st Comic Book Appearance Of Rocket Raccoon With Off-White To White Pages. -

Marvel Universe Thor Comic Reader 1 110 Marvel Universe Thor Comic Reader 2 110 Marvel Universe Thor Digest 110 Marvel Universe Ultimate Spider-Man Vol

AT A GLANCE Since it S inception, Marvel coMicS ha S been defined by hard-hitting action, co Mplex character S, engroSSing Story line S and — above all — heroi SM at itS fine St. get the Scoop on Marvel S’S MoSt popular characterS with thi S ea Sy-to-follow road Map to their greate St adventure S. available fall 2013! THE AVENGERS Iron Man! Thor! Captain America! Hulk! Black Widow! Hawkeye! They are Earth’s Mightiest Heroes, pledged to protect the planet from its most powerful threats! AVENGERS: ENDLESS WARTIME OGN-HC 40 AVENGERS VOL. 3: PRELUDE TO INFINITY PREMIERE HC 52 NEW AVENGERS: BREAKOUT PROSE NOVEL MASS MARKET PAPERBACK 67 NEW AVENGERS BY BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS VOL. 5 TPB 13 SECRET AVENGERS VOL. 1: REVERIE TPB 10 UNCANNY AVENGERS VOL. 2: RAGNAROK NOW PREMIERE HC 73 YOUNG AVENGERS VOL. 1: STYLE > SUBSTANCE TPB 11 IRON MAN A tech genius, a billionaire, a debonair playboy — Tony Stark is many things. But more than any other, he is the Armored Avenger — Iron Man! With his ever-evolving armor, Iron Man is a leader among the Avengers while valiantly opposing his own formidable gallery of rogues! IRON MAN VOL. 3: THE SECRET ORIGIN OF TONY STARK BOOK 2 PREMIERE HC 90 THOR He is the son of Odin, the scion of Asgard, the brother of Loki and the God of Thunder! He is Thor, the mightiest hero of the Nine Realms and protector of mortals on Earth — from threats born across the universe or deep within the hellish pits of Surtur the Fire Demon. -

AUG21 Westfield Catalog

AUG 2021 CATALOG ORDERS DUE AUGUST ??TH $4.25 WEB ORDERS DUE AUGUST 19TH AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #75 CATWOMAN: LONELY CITY #1 HOUSE OF SLAUGHTER #1 FOR ITEMS SCHEDULED TO SHIP BEGINNING IN OCTOBER 2021 FIND MORE DESCRIPTIONS, ART AND PRODUCTS AT WWW.WESTFIELDCOMICS.COM VENOM #1 You’ve never seen a Venom like this before! Find it in Marvel Comics! ARKHAM CITY: THE ORDER OF THE WORLD #1 Residents of Arkham Asylum walk among us. Find it in DC Comics! WonderWonder WomanWoman 80th80th AnniversaryAnniversary 100-Page100-Page SuperSuper SpectacularSpectacular #1#1 (One(One Shot)Shot) STAR TREK: MIRROR WAR #1 Picard and the Enterprise take the Mirror Universe by force. Find it in IDW! JEFFIFER BLOOD #1 The suburban housewife assassin returns. Find it in Dynamite! GUNSLINGER SPAWN #1 Can anyone outdraw the Gunslinger Spawn? Find it in Image Comics! JEN BARTEL - COSTUME CELEBRATION WRAPAROUND MARVEL MEOW HC See the Marvel Universe through the eyes of Captain Marvel’s cat, Chewie. Find it in Viz! FIND THESE AND ANY OTHER CataLOG LISTINGS AT CATALOGS WESTFIELDCOMICS.COM/SECTION/CataLOG-AUG21-CataLOGS WESTFIELD CATALOG (1ST CLASS USPS) – We will be mailing all our catalogs First Class so we are not offering a separate option for this. (You must order at least once every three months to continue to receive free catalog.) PREVIEWS PACKET - Hundreds of comics and graphic novels from the best comic publishers; the coolest pop-culture merchandise; plus exclusive items available nowhere else. Each packet includes Previews, Marvel Previews, DC Currents and a Previews Customer Order Form. $3.99 [21080003] WILL MURAI - CAT STAGGS - BRUCE TIMM - Also available sent Priority Mail, separate from your regular shipment and on the same day that Previews FILM INSPIRED TELEVISION INSPIRED ANIMATION INSPIRED hits the streets - this should take approximately 2-3 days. -

Portrayals of Midnighter and Apollo Wildstrom and Dc Comics

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2020 Regression and progression: portrayals of midnighter and apollo wildstrom and dc comics. Adam J. Yeich University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Yeich, Adam J., "Regression and progression: portrayals of midnighter and apollo wildstrom and dc comics." (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3462. Retrieved from https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd/3462 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGRESSION AND PROGRESSION: PORTRAYALS OF MIDNIGHTER AND APOLLO FROM WILDSTORM AND DC COMICS by Adam J. Yeich B.A., Kent State University at Stark, 2015 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2018 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In English Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2020 REGRESSION AND PROGRESSION: PORTRAYALS OF MIDNIGHTER AND APOLLO FROM WILDSTORM AND DC COMICS By Adam J. Yeich B.A., Kent State University at Stark, 2015 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2018 A Thesis Approved on April 1, 2020 by the following Thesis Committee _________________________ Dr. -

CITIZEN #149 Catalogue.Indd

Bien le bonjour à toutes et à tous ! Les mois se suivent et ne se ressemblent pas ! En effet, vous avez l’immense bonheur de recevoir ce Citizen en temps et en heure ! Si, si, c’est possible ! Si ça se trouve on va peut être même rééditer l’exploit le mois prochaine : mais ne soyons pas trop présomptueux ! édito En consultant notre brillant agenda, il me saute aux yeux que la date du 03 mai 2014 se rapproche à grand pas ! Vous n’avez pas oublié le FCBD quand même ? Sachez qu’en 2014, on va essayer/ten- ter/tâcher/s’efforcer… de faire encore mieux qu’en 2013… ou en 2012…ou en 2011….ou en 20… bref ! Ce millésime devrait vous plaire eu plus haut point, si vous n’êtes pas trop éloigné OU si vous vouliez profi ter d’une virée nordiste ce week-end sera votre week-end ! Je saute du coq à l’âne pour vous parler des actualités plus ou moins locales et des échéances qui nous attendent avec dans le désordre, le LCF édition 2014 qui peine à trouver une date et une salle malgré l’extrême dynamisme des membres du bureau, gageons que les résultats des élections municipales donneront des ailes aux « décideurs », un peu plus tard dans l’année, la présence du staff Astro au festival de Strasbourg « Strasbulles » semble prendre le bon chemin (avis aux abonnés du Grand Est….on arrive !) sans oublier la fi n de l’été qui sera marquée par la surpuissante Braderie de Lille (venez nombreux !) Si d’autres bonnes occasions se présentent sur notre chemin, nous ne manquerons pas de venir à votre rencontre ! Au menu de ce numéro 149, un peu d’autopromotion avec la courte séance photo de la page 12, vous êtes de plus en plus nombreux à recevoir le Citizen et certains d’entre vous ne nous connaissent pas « en vrai » ou encore la boutique que vous découvrirez sous divers angles ! news de MAI 2014 news Et j’en termine ce mois en vous signalant encore qu’il s’agit du #149, ce qui somme toute semble indiquer que le prochain numéro à sortir sera le ….roulement de tambour…150 et qui dit 150 dit numéro spécial avec des surprises, avec des …oups, je n’en dis pas plus. -

CITIZEN #154 Catalogue.Indd

Bien le bonjour à toutes et à tous ! Le compte à rebours était lancé, sachant que la période de juillet/août reste une charnière sensible et que nous devons négocier au mieux les temps de présence/ édito absence/présence… l’essentiel est là ! Qui plus est, vous le tenez dans vos mains toutes palpitantes d’excitation… le Citizen, cent cinquante-troisième du nom, est imprimé ET expédié ! La « nouvelle » maquette ayant- semble-t-il -plu au plus grand nombre, nous la reconduisons donc ! Ceci étant dit, je ne me lasse pas ( !) de vous re-transmettre l’info concernant une nouvelle pratique postale, sachez donc que Coliposte nous (et vous) propose des solutions innovantes et compétitives… à ce titre, les informations transmises dans les imprimés et sur les étiquettes sont des données essentielles à la li- vraison des colis, une information manquante a un impact direct sur le service de livraison. Plus important encore : les surcouts liés à la non-conformité des annonces donnent lieu à l’application de plusieurs suppléments tarifaires : en cas d’absence d’adresse email / téléphone sur l’étiquette le surcout est de 0.10€ par colis ! Je vous propose donc : -1- de nous communiquer une adresse email (qui servira de plus à Coliposte pour vous prévenir de l’arrivée imminente de votre colis)…..OU………… -2- de refuser de communiquer votre adresse email et, dans ce cas, l’adresse email d’AstroCity sera apposée (vous conservez votre anonymat mais ne pourrez news d’OCTOBRE 2014 d’OCTOBRE news recevoir d’avis de passage numérique) A vous de me donner votre réponse sur le bon de commande du mois ! Et merci !!! la cover du mois : L’équipe d’Astro (Damien, Fred & Jérôme) MARVEL 75th ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION #1 par Paolo Rivera Le logo astrocity et la super-heroïne Un peu de lexique.. -

Marvel September to December 2021

MARVEL Marvel's Black Widow: The Art of the Movie Marvel Comics Summary After seven appearances, spanning a decade in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Natasha Romanoff , a.k.a. the Black Widow, takes the lead in an adventure unlike any other she's known before. Continuing their popular ART OF series of movie tie-in books, Marvel presents another blockbuster achievement! Featuring exclusive concept artwork and in-depth interviews with the creative team, this deluxe volume provides insider details about the making of the highly anticipated film. Marvel 9781302923587 On Sale Date: 11/23/21 $50.00 USD/$63.00 CAD Hardcover 288 Pages Carton Qty: 16 Ages 0 And Up, Grades P to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 27.6 cm H | 18.4 cm W The Marvels Vol. 1 Kurt Busiek, Yildiray Cinar Summary Kurt Busiek (MARVELS) is back, with the biggest, wildest, most sprawling series you’ve ever seen — telling stories that span decades and range from cosmic adventure to intense human drama, from street-level to the far reaches of space, starring literally anyone from Marvel’s very first heroes to the superstars of tomorrow! Featuring Captain America, Spider-Man, the Punisher, the Human Torch, Storm, the Black Cat, the Golden Age Vision, Melinda May, Aero, Iron Man, Thor and many more — and introducing two brand-new characters destined to be fan-favorites — a thriller begins that will take readers across the Marvel Universe…and beyond! Get to know Kevin Schumer, an ordinary guy with some big secrets — and the mysterious Threadneedle as well! But who (or what) is KSHOOM? It all starts here.