IN-CHIEF / EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. Dr. Bahattin P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinefan 2006

Cinefan 2006 By Ron Holloway Fall 2006 Issue of KINEMA CINEFAN NEW DELHI FESTIVAL 2006 When I asked an informed critic for an opinion as to which was the most important film festival in India today, he named Osian’s Cinefan in a close tie with the Trivandrum International Film Festival - with the caveat, of course, that Cinefan in New Delhi primarily presents Asian cinema, while Trivandrum (aka Triruvananthapuram, to use the official name) in Kerala opens its doors wide to international film fare.As for the long-running International Film Festival in India (IFFI), a government-sponsored affair based in Goa for the past couple of years, I was told that it ranked third at best, although a larger attendance was recorded last year. In other words, Goa, a resort city populated mostly by tourists from home and abroad, has had to work hard to attract a movie-mad Indian public from across the country. Two other festivals were also thrown into the melee: Kolkata (Calcutta) and Mumbai (Bombay), both feeding upon major production centres with long traditions for supporting auteur directors. Some other Indian film festivals were named in passing - the Mumbai International Festival of Documentaries, Shorts, and Animation Films, for instance. And there’s also a growing film festival in Pune, where the country’s National Film Archive and National Film School are located. Under the tireless leadership of Osian’s Neville Tuli (founder-chairman) and Cinefan’s Aruna Vasudev (founder-director), the 8th Osian’s Cinefan Festival of Asian Cinema in New Delhi (14-23 July 2006) set new standards of Asian cinema excellence. -

Two Films: Devi and Subarnarekha and Two Masters of Cinema / Partha Chatterjee

Two Films: Devi and Subarnarekha and Two Masters of Cinema / Partha Chatterjee Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak were two masters from the Bengali cinema of the 1950s. They were temperamentally dissimilar and yet they shared a common cultural inheritance left behind by Rabindranath Tagore. An inheritance that was a judicious mix of tradition and modernity. Ray’s cinema, like his personality, was outwardly sophisticated but with deep roots in his own culture, particularly that of the reformist Brahmo Samaj founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy to challenge the bigotry of the upper caste Hindu Society in Bengal in the early and mid-nineteenth century. Ghatak’s rugged, home- spun exterior hid an innate sophistication that found a synthesis in the deep-rooted Vaishnav culture of Bengal and the teachings of western philosophers like Hegel, Engels and Marx. Satyajit Ray’s Debi (1960) was made with the intention of examining the disintegration of a late 19th century Bengali Zamidar family whose patriarch (played powerfully by Chabi Biswas) very foolishly believes that his student son’s teenaged wife (Sharmila Tagore) is blessed by the Mother Goddess (Durga and Kali) so as able to cure people suffering from various ailments. The son (Soumitra Chatterjee) is a good-hearted, ineffectual son of a rich father. He is in and out of his ancestral house because he is a student in Calcutta, a city that symbolizes a modern, scientific (read British) approach to life. The daughter-in-law named Doyamoyee, ironically in retrospect, for she is victimized by her vain, ignorant father-in-law, as it to justify the generous, giving quality suggested by her name. -

The Cinema of MF Husain,Water As a Metaphor in Indian

The Cinema of M.F. Husain M.F. Husain’s two feature length fiction films, Gaja Gamini and Meenaxi are classic examples of having one’s cake and eating it too. In each case, the cake is delectable. True that the two films are not for a mass audience whatever that may mean, but that there is a sizeable audience for them, mainly urban, is beyond dispute. Had they been promoted properly, there would have been jam for the distributors and exhibitors. These two films are genuinely experimental and also eminently accessible to those with open minds-not necessarily intellectual or in tune with European Cinema-but just receptive to new ideas. They share certain avant-garde qualities with Ritwik Ghatak’s ‘Komal Gandhar’ (1961) and are even more advanced in terms of ideas and equally fluid in execution. It is both unfair and unrealistic to compare Husain’s achievements with that of other artists – painters and sculptures – who have also made films. In 1967, his Short, Through The Eyes of a Painter won the top prize in its category at the Berlin Film Festival. Shortly afterwards, an illustrious colleague Tyeb Mehta also made a Short for the same producer, Films Division of India (Government run) in which a slaughterhouse figured prominently. It too was widely appreciated. Then Gopi Gajwani, a painter who also worked with Span Magazine an organ of the United States Information Service, made from his own pocket two abstract short films in 35mm. They were shown once or twice and disappeared for nearly 30 years only to surface during the recent Golden Jubilee Celebrations of Lalit Kala Akademi. -

Deconstruction of Men and Masculinities in the Post- Partition Alternative Indian Cinema (The 1950S to 1980S)

P a g e | 1 Article Debjani Halder Deconstruction of Men and Masculinities in the Post- Partition Alternative Indian Cinema (the 1950s to 1980s) “Fundamentally Popular Hindi cinema has been a hero-dominated discourse where the close psychological conflict between oppositional forces like the good (hero) and evil (bad) always extends through the narratives. In the context of early Indian cinema, especially in the forties, fifties and sixties, the hero represented an as masculine archetypal image. As an example, the mythological characters like Shiva Hanuman, Krishna, Narayana always symbolised as the archetypal Macho. Apparently, in between the 1930s to 1940s hero depicted as the pillar of unconditional love, those are criticised as the weak hero or feminine man (as of example Dilip Kumar in Devdas, Guru Dutt in Piyasa). In the 1960s, we observed the representation of a positive hero (like Shammi Kapoor), who was optimistic and believed that affluence was around the corner and the better things would go to happen immediately. But in the 1970s the scenario had been changed. It was depicted that the positive dream got shattered, which had created a kind of cynicism and anger. In the aspect of mainstream cinema, there is no similarity between the hero and a common man. The hero always depicted as larger than life. In the context of mainstream popular Hindi films while the hero depicted as the unidimensional subject, vis-à-vis heroine rendered as the submissive object. In the mainstream cinema, the hero has specific mystique images, which scaled to the star ladder. Like Rajesh Khanna represented as the eternal romantic. -

Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-24-2015 12:00 AM "More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema Sarbani Banerjee The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Prof. Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sarbani, ""More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3125. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3125 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i “MORE OR LESS” REFUGEE? : BENGAL PARTITION IN LITERATURE AND CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Sarbani Banerjee Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I problematize the dominance of East Bengali bhadralok immigrant’s memory in the context of literary-cultural discourses on the Partition of Bengal (1947). -

Modernity and Material Culture in Bengali Cinema, 1947-1975

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-20-2011 12:00 AM Alternative Be/longing: Modernity and Material Culture in Bengali Cinema, 1947-1975 Suvadip Sinha University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Suvadip Sinha 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Other English Language and Literature Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sinha, Suvadip, "Alternative Be/longing: Modernity and Material Culture in Bengali Cinema, 1947-1975" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 137. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/137 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alternative Be/longing: Modernity and Material Culture in Bengali Cinema, 1947-1975 (Spine Title: Alternative Be/longing) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Suvadip Sinha Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Suvadip Sinha 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners _____________________ _ ________________________ Dr. -

Dossier De Presse Ghatak

Dossier de presse RÉTROSPECTIVE RITWIK GHATAK du 1er au 15 juin 2011 En partenariat média avec Un des grands artistes de l’histoire du cinéma indien. Son œuvre, trop courte, soumet le mélodrame, la chronique sociale ou la fresque historique à un traitement singulier. La Rivière Subarnarekha de Ritwik Ghatak (Inde/1962-65) - DR FILM + TABLE RONDE « Ritwik Ghatak, un cinéaste du Bengale » Samedi 4 juin à 14h30 À la suite de la projection, à 14h30, de Raison, discussions et un conte (1974, 121’) rencontre avec Sandra Alvarez de Toledo, France Bhattacharya, Raymond Bellour, Nikola Chesnais et Charles Tesson . Rencontre animée par Christophe Jouanlanne. Billet unique : Film + Table Ronde / Tarif plein 6.5€ - Tarif réduit 5€ - Forfait Atout prix et Cinétudiant 4€ /Libre pass : accès libre ACTUALITÉ EN LIBRAIRIE : Ritwik Ghatak. Des films du Bengale de Sandra Alvarez de Toledo (dir.) Éditions L’Arachnéen, 416 pages, 430 images. 39€. Cette rétrospective coïncide avec la sortie d’un livre, Ritwik Ghatak. Des films du Bengale , le premier en France et le seul de cette importance à lui être consacré. (Voir page 10) CONTACT PRESSE CINEMATHEQUE FRANCAISE Elodie Dufour Tél. : 01 71 19 33 65 / 06 86 83 65 00 / [email protected] FORCE DE GHATAK Par Raymond Bellour Ritwik Ghatak est l’un des grands artistes de l’histoire du cinéma indien. Son œuvre, trop courte (8 longs métrages), soumet le mélodrame, la chronique sociale ou la fresque historique à un traitement singulier, traversé par des éclats de poésie. Comment décrire les films de Ritwik Ghatak, l’un des plus méconnus parmi les très grands cinéastes ? Disons, si comparaison vaut raison : Ghatak, ce serait Sirk (qu’il ignore, comme presque tout le cinéma américain, si ce n’est Ford qu’il nomme une fois « un artiste considérable ») et Eisenstein (son cinéaste de chevet). -

Cinema of India - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Cinema of India - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_film Cinema of India From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Indian film) The cinema of India consists of films produced across India, including the cinematic culture of Mumbai along with the cinematic traditions of states such as Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Karnataka, Kerala, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. Indian films came to be followed throughout South Asia and the Middle East. As cinema as a medium gained popularity in the country as many as 1,000 films in various languages of India were produced annually. Expatriates in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States continued to give rise to international audiences for Hindi-language films. Devi in the 1929 film, Prapancha Pasha (A Throw of Dice), directed by Franz Osten.jpg|thumb|Charu Roy and Seeta Devi in the 1929 film, Prapancha Pash . In the 20th century, Indian cinema, along with the American and Chinese film industries, became a global enterprise. [1] Enhanced technology paved the way for upgradation from established cinematic norms of delivering product, radically altering the manner in which content reached the target audience. [1] Indian cinema found markets in over 90 countries where films from India are screened. [2] The country also participated in international film festivals especially satyajith ray(bengali),Adoor Gopal krishnan,Shaji n karun(malayalam) . [2] Indian filmmakers such as Shekhar Kapur, Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta etc. found success overseas. [3] The Indian government extended film delegations to foreign countries such as the United States of America and Japan while the country's Film Producers Guild sent similar missions through Europe. -

Bengali Political Cinema: Protest and Social Transformation

Bengali Political Cinema: Protest and Social Transformation by Naadir Junaid A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences April 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements і Dedication v Introduction Political Cinema, Third Cinema and Bengali Cinema of Liberation 1 Chapter One Bengali Politically-Committed Cinema: A Historiography 44 Chapter Two Speaking Out against Social Injustice through Cinema: Mrinal Sen’s Calcutta 71 (1972) 89 Chapter Three Preference for Personal Protest in Political Cinema: Satyajit Ray’s Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970) 138 Chapter Four Cinema of Decolonization under Military Rule: Zahir Raihan’s Jiban Theke Neya (Glimpses from Life, 1970) 180 Chapter Five Cultural Resistance and Political Protest through Allegory: Tareque Masud’s Matir Moina (The Clay Bird, 2002) 224 Conclusion 265 Bibliography 274 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the Government of Australia for awarding me an Endeavour Scholarship. This scholarship enabled me to do a PhD in Australia. My deepest thanks are due to all individuals who helped me when I was completing my thesis. A number of individuals deserve special mention for the tremendous support they gave me during my journey towards the successful completion of my thesis. First and foremost, I would like to express my grateful and heartfelt thanks to my supervisor, Professor George Kouvaros. I strongly believe getting the opportunity to work under his supervision was the best thing that happened during my PhD candidature. His intellectual guidance, insightful comments and constructive criticisms profoundly influenced my own intellectual development and helped me gain greater understanding of film research. -

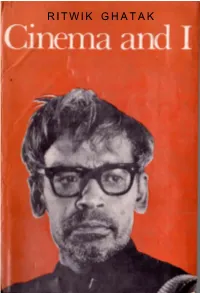

Ritwik Ghatak

RITWIK GHATAK Ritwik Ghatak Cinema and I First Published 17th January 1987 Published by Ritwik Memorial Trust With support from Federation of Film Societies of India © Ritwik Memorial Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented. Including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission In writing from the publisher. Cover designed by Satyajit Ray Cover photograph from Jukti Takko ArGappo Photo type setting by Pratikshan Publications Pvt. Ltd Reproduced by Quali Photo Process Pvt. Ltd Printed at A O P (India) Pvt. Ltd Distributed exclusively in India by Post Box No. 12333 15 Bankim Chatterjee Street Calcutta-700 073 Branches: Allahabad. Bombay, New Delhi, Bangalore. Madras, Hyderabad. RITWIK MEMORIAL TRUST 1/10 Prince Golam Mohd Road Calcutta-700 026 The present volume is the first in the series of publications of Ritwik Ghatak's works entitled Ritwik Rachana Samagra. Contents Publisher's note 9 Acknowledgements 10 Foreword by Satyajit Ray 11 Film and 1 13 My Coming into films 19 Bengali Cinema: Literary Influence 21 What Ails Indian Film-Making 26 Some Thoughts on Ajantrik 31 Experimental Cinema 34 Sound in Film 38 Music in Indian Cinema and the Epic Approach 41 Experiment in Cinema and I 44 Documentary: the Most Exciting form of Cinema 46 Cinema and the Subjective Factor 60 Film-Making 65 Interview (1) 68 Interview (2) 77 Nazarin 81 A book review: Theory of Film 84 An Attitude to life and an Attitude to Art Appendix About Oraons (Chotonagpur) 91 Check-list 105 Publisher's Note Ritwik Ghatak's creative exercises spanned through many a medium of expression—poetry, short story, play, film. -

Film-Utsav Schedule

The Museum of Modern Art Department of Film 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART FILM-UTSAV INDIA Part I: PROFILES; October 25 - December 15, 1985 Schedule Unless otherwise noted, all films will be screened in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 and wTl 1 be spoken in Hindi with English subtitled Friday, October 25 at 2:00 p.m.: Aag (Fire). 1948. Raj Kapoor. With Raj Kapoor, Nargis. 140 min. Friday, October 25 at 6:00 p.m.: Awara (The Vagabond). 1951. Raj Kapoor. With Raj Kapoor, Nargis, Prithviraj Kapoor. 170 min. TOTAPOOR WILL INTRODUCE THE FILM. Saturday, October 26 at 1:00 p.m.: Awara (The Vagabond). See Friday, October 25 at 6:00 p.m. Saturday, October 26 at 5:00 p.m.: Aag (Fire). See Friday, October 25 at 6:00 p.m. Sunday, October 27 at 1:00 p.m.: Shree 420 (Mr. 420). 1955. Raj Kapoor. With Raj Kapoor, Nargis, Nadira. 169 min. Sunday, October 27 at 5:00 p.m.: Boot Polish. 1954. Produced by Raj Kapoor, directed by Prakash Arora. With Baby Naaz, Ratan Kumar, and David. 140 min. Monday, October 28 at 2:30 p.m.: Boot Polish. See Sunday, October 27 at 5:00 p.m. Monday, October 28 at 6:00 p.m.: Shree 420 (Mr. 420). See Sunday, October 27 at 1:00 p.m. Saturday, November 2 at 1:00 p.m.: Barsaat (Monsoon). 1949. Raj Kapoor. With Raj Kapoor, Nargis, Premnath. 164 min. Saturday, November 2 at 5:00 p.m.: Satyam Shivam Sundaram (Love Sublime/Love Truth and Beauty). -

An Analysis of Ritwik Ghatak's Cinema

PARTITION AND THE BETRAYAL OF INDIA’S INDEPENDENCE: AN ANALYSIS OF RITWIK GHATAK’S CINEMA Diamond Oberoi Vahali Ambedkar University, Delhi Abstract At Partition the dream of India’s independence from British colonial rule transformed itself into the horrific nightmare of communal violence. Ritwik Ghatak, one of the most impor- tant film makers of India, served the crucial function of chronicling this mass tragedy. The independence of India resulted not only in the partition of the subcontinent but in the mass migration of people. This inevitably led people to homelessness, unemployment, segregation and abject impoverishment. However, the reduction of the middle class into the lower class was not because of partition alone but also a result of the anti-people model that the Indian government adopted post-independence. This chapter will look at the ongoing trauma of Partition and the way the people experienced it by analysing Ritwik Ghatak’s films. Keywords: Betrayal, Exodus, Ritwik Ghatak, Homelessness, Independence, Partition, refugees. Resumen 91 La Partición convirtió el sueño de emancipación de India en una pesadilla de violencia religiosa. Ritwik Ghatak, uno de los mejores cineastas indios, hizo de su obra una crónica de aquella tragedia. La Independencia no supuso ya la división del subcontinente en dos países, sino también un trasvase de población sin precedentes, con las consecuencias de personas sin hogar, desempleo, segregación y miseria. Por otra parte, el descenso social de la clase media iniciado con el proceso de independencia se vio agravado por las políticas antipopulares d el gobierno indio. Este artículo estudia el trauma de la Partición en la obra de Ritwik Ghatak.