'Located on the Precipices and Pinnacles' a Report on the Waimarino Non-Seller Blocks and Seller Reserves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule D Part3

Schedule D Table D.7: Native Fish Spawning Value in the Manawatu-Wanganui Region Management Sub-zone River/Stream Name Reference Zone From the river mouth to a point 100 metres upstream of Manawatu River the CMA boundary located at the seaward edge of Coastal Coastal Manawatu Foxton Loop at approx NZMS 260 S24:010-765 Manawatu From confluence with the Manawatu River from approx Whitebait Creek NZMS 260 S24:982-791 to Source From the river mouth to a point 100 metres upstream of Coastal the CMA boundary located at the seaward edge of the Tidal Rangitikei Rangitikei River Rangitikei boat ramp on the true left bank of the river located at approx NZMS 260 S24:009-000 From confluence with Whanganui River at approx Lower Whanganui Mateongaonga Stream NZMS 260 R22:873-434 to Kaimatira Road at approx R22:889-422 From the river mouth to a point approx 100 metres upstream of the CMA boundary located at the seaward Whanganui River edge of the Cobham Street Bridge at approx NZMS 260 R22:848-381 Lower Coastal Whanganui From confluence with Whanganui River at approx Whanganui Stream opposite Corliss NZMS 260 R22:836-374 to State Highway 3 at approx Island R22:862-370 From the stream mouth to a point 1km upstream at Omapu Stream approx NZMS 260 R22: 750-441 From confluence with Whanganui River at approx Matarawa Matarawa Stream NZMS 260 R22:858-398 to Ikitara Street at approx R22:869-409 Coastal Coastal Whangaehu River From the river mouth to approx NZMS 260 S22:915-300 Whangaehu Whangaehu From the river mouth to a point located at the Turakina Lower -

Errata and Updated Statistics for the 2014 Annual Climate Summary Issued

Errata and updated statistics for the 2014 Annual Climate Summary Issued: 16 April 2015 Every year, an annual climate summary and a table of annual statistics are provided by NIWA, usually within the first two weeks of January. This summary is based on data available at the time, and often includes preliminary (real-time) annual climate statistics which are as yet not fully quality checked. Each year during April, the annual statistics from the calendar year prior are updated, including both automated and manual climate station data. The purpose of the update is two-fold; to enable manual climate data to be incorporated, since manual stations typically take 1-2 months for data to be received and entered into the National Climate Database; and to log errata found in subsequent quality checks performed in the National Climate Database, or site visits undertaken in January and February. This update is for the 2014 annual climate summary. This update was based on available data as at 1 April 2015. Errata and notes 1. Following the update of station data contained within the Water Resources Archive, the rankings for wettest sites in New Zealand for 2014 have changed. The wettest four locations are now: Cropp River at Waterfall (11866 mm), Tuke River at Tuke Hut (10728 mm), Cropp River at Cropp Hut (10655 mm), and Haast River at Cron Creek (8239 mm). 2. Offshore and outlying island stations were not included in this update. 3. Some sites have missing days of data. The number of missing days is indicated by a superscript number next to the annual value in the tables below. -

New Zealand Gazette

:_ >&;r'"-'. ~:~ ',~ .' ; ',' I Jttmb. 53.) 1733 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 6, 192:J. Crawn Land set apart for DilJ'f)Odal by way o.f Sale w Lease Ihowever, to the conditions prescribed by section fifty-one of to Discharged Soldiers, under Special Ten,,res, in the the last-mentioned Act, and section fifteen of the Native Land Taranaki Land Diatrict. Amendment Act, 1914: And whereas the said Court is of the opinion that in the tL.S.J JELL I COE, Governor-General. public interest the said road.Jines should be proclaimed as public roads, l'nd a notification to that effect has been for A PROCLAMATION. warded to the :Minister of Lands, in terms of section fifty-one N pursuance of the power and authority conferred upon of the Native Land Amendment Act, 1913: I me by section four of the Discharged Soldiers Settle And whereas one month's notice in writing of the intention ment Act, 1915, I, John Rushworth, Viscount Jellicoe, to proclaim the said road-lines as public roads has been given Governor - General of the Dominion of New Zeala.nd, do by the Surveyor-General to the local authority of the district hereby procla.im and decla.re that the area of ~wn la.nd concerned, in terms of section fifteen of the Native Land described in the Schedule hereto shall be and the same is Amendment Act, 1914: hereby set apart and decla.red open for disposal by way of sale And whereas it is now expedient that the said road-lines or lease to discharged soldiers, under special tenures, in the should be proclaimed as public roads : manner provided in the said· Act. -

Ruapehu College

RUAPEHU COLLEGE Seek further knowledge Newsletter Ruapehu College, at the heart of our community and the college of choice, making a mountain of difference in learning and for life. Principal: Kim Basse Newsletter 15—23 October 2018 Email : [email protected] Phone: 06 3858398 Help Tui Wikohika on his journey to compete at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics In Snowboard Slopestyle and Big Air. There has been a Pledge Me page set up for donations https://www.pledgeme.co.nz/projects/5855-help-tui-wikohika-on-his-journey-to-compete-at-the-2022-beijing- winter-olympics-in-snowboard-slopestyle-and-big-air?fbclid=IwAR1FEac1W9- 3IhkmqpWwXDXQqpqh0qCiGByR3R5PtrqmH4BjCSNAAySdfn0 Tui Wikohika is a 14 year old snowboarder from Raetihi NZ, who has dreams of making the NZ Olympic team in freestyle snowboarding. Tui's journey towards his dream has involved many hours of training, hard work and sacrifice. Tui's aspirations and vision for the sport has seen him working part time since he was at primary school and after training to help fund his travel to training camps and competitions around NZ. Tui is currently ranked 2nd in NZ for U16 boys snowboarding after a successful nationals campaign. Tui aims to travel to Colorado and Canada over the 2019 NZ summer to train and compete in world class facilities against American and Canadian athletes. This will help prepare Tui for a big NZ Winter season next year where he hopes to compete on the world junior rookie tour and all FIS sanctioned events. These events will give him a world ranking where he can track his progress against international riders. -

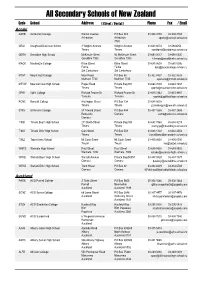

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Agenda of Environment Committee

I hereby give notice that an ordinary meeting of the Environment Committee will be held on: Date: Wednesday, 29 June 2016 Time: 9.00am Venue: Tararua Room Horizons Regional Council 11-15 Victoria Avenue, Palmerston North ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE AGENDA MEMBERSHIP Chair Cr CI Sheldon Deputy Chair Cr GM McKellar Councillors Cr JJ Barrow Cr EB Gordon (ex officio) Cr MC Guy Cr RJ Keedwell Cr PJ Kelly JP DR Pearce BE Rollinson Michael McCartney Chief Executive Contact Telephone: 0508 800 800 Email: [email protected] Postal Address: Private Bag 11025, Palmerston North 4442 Full Agendas are available on Horizons Regional Council website www.horizons.govt.nz Note: The reports contained within this agenda are for consideration and should not be construed as Council policy unless and until adopted. Items in the agenda may be subject to amendment or withdrawal at the meeting. for further information regarding this agenda, please contact: Julie Kennedy, 06 9522 800 CONTACTS 24 hr Freephone : [email protected] www.horizons.govt.nz 0508 800 800 SERVICE Kairanga Marton Taumarunui Woodville CENTRES Cnr Rongotea & Hammond Street 34 Maata Street Cnr Vogel (SH2) & Tay Kairanga-Bunnythorpe Rds, Sts Palmerston North REGIONAL Palmerston North Wanganui HOUSES 11-15 Victoria Avenue 181 Guyton Street DEPOTS Levin Taihape 11 Bruce Road Torere Road Ohotu POSTAL Horizons Regional Council, Private Bag 11025, Manawatu Mail Centre, Palmerston North 4442 ADDRESS FAX 06 9522 929 Environment Committee 29 June 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Apologies and Leave of Absence 5 2 Public Speaking Rights 5 3 Supplementary Items 5 4 Members’ Conflict of Interest 5 5 Confirmation of Minutes Environment Committee meeting, 11 May 2016 7 6 Environmental Education Report No: 16-130 15 7 Regulatory Management and Rural Advice Activity Report - May to June 2016 Report No: 16-131 21 Annex A - Current Consent Status for WWTP's in the Region. -

The New Zealand Police Ski Club Information Site

WELCOME TO THE NEW ZEALAND POLICE SKI CLUB INFORMATION SITE Established in 1986, the NZ Police Ski Club Inc was formed when a group of enthusiastic Police members came together with a common goal of snow, sun and fun. In 1992 the Club purchased an existing property situated at 35 Queen Street, Raetihi that has over 40 beds in 12 rooms. It has a spacious living area, cooking facilities, a drying room and on-site custodians. NZPSC, 35 Queen Street, Raetihi 4632, New Zealand Ph/Fax 06 385 4003 A/hours 027 276 4609 email [email protected] Raetihi is just 11 kilometres from Ohakune, the North Island’s bustling ski town at the south-western base of the mighty Mt Ruapehu, New Zealand’s largest and active volcano. On this side of the mountain can be found the Turoa ski field. Turoa ski field boasts 500 hectares of in boundary terrain. The Whakapapa ski field is on the north-west side of the mountain and is about 56 kilometres from Raetihi to the top car park at the Iwikau Village. Whakapapa has 550 hectares of in boundary terrain. You don't need to be a member of the Police to join as a Ski Club member or to stay at the Club! NZPSC, 35 Queen Street, Raetihi 4632, New Zealand Ph/Fax 06 385 4003 A/hours 027 276 4609 email [email protected] More Stuff!! The Club hosts the New Zealand Police Association Ski Champs at Mt Ruapehu and in South Island ski fields on behalf of the Police Council of Sport and the Police Association. -

Mountains to Sea / Nga Ara Tuhono Cycleway — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa

10/1/2021 Mountains to Sea / Nga Ara Tuhono Cycleway — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa Mountains to Sea / Nga Ara Tuhono Cycleway Mountain Biking Difculties Medium , Hard Length 294.1 km Journey Time 3 to 6 days cycling Region Manawatū-Whanganui Sub-Regions Ruapehu , Whanganui Part of the Collection Nga Haerenga - The New Zealand Cycle Trail https://www.walkingaccess.govt.nz/track/mountains-to-sea-nga-ara-tuhono-cycleway/pdfPreview 1/5 10/1/2021 Mountains to Sea / Nga Ara Tuhono Cycleway — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa From the fringes of Mt Ruapehu to the coastal shores of Whanganui, this route encompasses majestic mountains, stunning native forest within two National Parks, and the spiritual, cultural and historical highlights of the Whanganui River. The Mountains to Sea Cycle Trail takes in the alpine grandeur of Mt Ruapehu, historic coach road and bridle trails, the legendary Bridge to Nowhere, jet boat and kayak transport options for the Whanganui River link to Pipiriki. From there a country road trail abundant with history and culture alongside the Whanganui River links Pipiriki to the Tasman Sea at Whanganui. The trail is a joint initiative involving the Ruapehu District Council, Whanganui Iwi, Whanganui District Council, Department of Conservation and the New Zealand Cycle Trail project. Suitable for all abilities of cyclists, the trail includes a mixture of off and on-road trail, which can be enjoyed in sections or in its entirety. It’s recommended that you start from Ohakune which offers a 217km journey [including a 32k river section which will be completed by boat or kayak] which is a grade 2-3 ride. -

ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT // 01.07.11 // 30.06.12 Matters Directly Withinterested Parties

ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT // 01.07.11 // 30.06.12 2 1 This report provides a summary of key environmental outcomes developed through the process to renew resource consents for the ongoing operation of the Tongariro Power Scheme. The process to renew resource consents was lengthy and complicated, with a vast amount of technical information collected. It is not the intention of this report to reproduce or replicate this information in any way, rather it summarises the key outcomes for the operating period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. The report also provides a summary of key result areas. There are a number of technical reports, research programmes, environmental initiatives and agreements that have fed into this report. As stated above, it is not the intention of this report to reproduce or replicate this information, rather to provide a summary of it. Genesis Energy is happy to provide further details or technical reports or discuss matters directly with interested parties. HIGHLIGHTS 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012 02 01 INTRODUCTION 02 1.1 Document Overview Rotoaira Tuna Wananga Genesis Energy was approached by 02 1.2 Resource Consents Process Overview members of Ngati Hikairo ki Tongariro during the reporting period 02 1.3 How to use this document with a proposal to the stranding of tuna (eels) at the Wairehu Drum 02 1.4 Genesis Energy’s Approach Screens at the outlet to Lake Otamangakau. A tuna wananga was to Environmental Management held at Otukou Marae in May 2012 to discuss the wider issues of tuna 02 1.4.1 Genesis Energy’s Values 03 1.4.2 Environmental Management System management and to develop skills in-house to undertake a monitoring 03 1.4.3 Resource Consents Management System and management programme (see Section 6.1.3 for details). -

Meringa Station Forest

MERINGA STATION FOREST Owned by Landcorp Farming Ltd Forest Management Plan For the period 2016 / 2021 Prepared by Kit Richards P O Box 1127 | Rotorua 3040 | New Zealand Tel: 07 921 1010 | Fax: 07 921 1020 [email protected] | www.pfolsen.com FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN MERINGA STATION FOREST Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................2 2. Forest Investment Objectives ......................................................................................................3 OPERATING ENVIRONMENT .....................................................................................................................5 3. Forest Landscape Description .....................................................................................................5 Map 1: Meringa Station Forest Location Map .........................................................................................7 4. The Ecological Landscape ............................................................................................................8 Map 2: Forest by Threatened Environments Classification .................................................................. 10 5. Socio-economic Profile and Adjacent Land .............................................................................. 11 6. The Regulatory Environment .................................................................................................... 13 FOREST MANAGEMENT ........................................................................................................................ -

Councilmark Assessment Report Ruapehu District Council 2017

Ruapehu District Council Independent assessment report | July 2017* An independent assessment report issued by the Independent Assessment Board for the CouncilMARK™ local government excellence programme. For more information visit www.councilmark.co.nz 1 MBIE 2016 2 Stats NZ Census 2013 3 DIA 2013 4* Ministry Period of ofTransport assessment: 2013/14 February 2017 Ruapehu District Council assessment report 1 Assessment Summary AT A GLANCE Ruapehu District Council is part of a geographically large district with small, diverse rural communities, many with challenging social demographics. The current situation Ruapehu District Council is small, serving a population of less than 12,000. It shares territory with two national parks, the World Heritage Tongariro National Park to the east and the Whanganui National Period of assessment Park to the west. Its major towns are Ohakune, Raetihi, and The assessment took place on 9 and 10 February 2017. Taumarunui. The resident population has declined but the Council believes that this has now stabilised. Tourism has grown in importance and is expected to continue to grow. Conversely, it is not anticipated that any future non-tourist business closures will have a substantial economic impact as there are few major employers left in the area. The Council is actively pursuing a strategy of developing tourism and being increasingly business- friendly. The current resident population is ageing, and there is a upward drift in the number of non-resident properties. 2 CouncilMARKTM $505m GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT1 -

Contextual Material on Maori and Socio-Economic Issues in the National Park Inquiry District, 1890 - 1990

Wai 1130 # A57 - 3 FEB 2006 Ministry of J'ustice WELLINGTON Contextual Material on Maori and Socio-Economic Issues in the National Park Inquiry District, 1890 - 1990: A Scoping Report Leanne Boulton February 2006 Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal for the National Park District Inquiry (Wai 1130) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................7 1. AUTHOR .......................................................................................................................................7 2. THE COMMISSION .......................................................................................................................7 3. METHODOLOGY ..........................................................................................................................8 A) GEOGRAPHICAL COVERAGE OF THE REPORT ..............................................................................8 B) SOURCES AND SCOPING TECHNIQUE ...........................................................................................9 C) STATISTICAL RESEARCH ..............................................................................................................9 4. CLAIMANT ISSUES .....................................................................................................................10 4.1. GENERAL PREJUDICE SUFFERED .............................................................................................10 4.2. ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES.....................................................................................................10