Leaving Hinduism: Deconversion As Liberation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

Roshni JULY to SEPTEMBER 2020

Members of Purva Vidarbha Mahila Parishad, Nagpur, Celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi Roshni JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2020 ALL INDIA Women’s ConferenCE Printed at : I G Printers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi-110020 Maharashtra Celebrates Ganesh Chaturthi Ganesh Puja at the home of President -AIWC, Ganesh Puja at the home of President -Mumbai Branch, Smt. Sheela Kakde Smt. Harsha Ladhani Independence Day Celebrations at Head Office Ganesh Puja at Pune Mahila Mandal ROSHNI Contents Journal of the All India Women's Conference Editorial ...................................................................... 2 July - September 2020 President`s Keynote Address at Half Yearly Virtual Meeting .................................... 3 EDITORIAL BOARD -by Smt. Sheela Kakde Editor : Smt. Chitra Sarkar Assistant Editor : Smt. Meenakshi Kumar Experience at Hathras ............................................... 6 Advisors : Smt. Rekha A. Sali -by Smt. Kuljit. Kaur : Smt. Sheela Satyanarayan Editorial Assistants : Smt. Ranjana Gupta An Incident in Hyderabad… How we reacted .... 10 : Smt. Sujata Shivya -by Smt. Geeta Chowdhary President : Smt. Sheela Kakde Maharani Chimnabai II Gaikwad Secretary General : Smt. Kuljit Kaur Treasurer : Smt. Rehana Begum The Illustrious First President of AIWC. .............. 11 -by Smt. Shevata Rai Talwar, Patrons : Smt. Kunti Paul : Dr. Manorama Bawa Are Prodigies Made or Born- A Tribute : Smt. Gomathi Nair to Sarojini Naidu ...................................................... 15 : Smt. Bina Jain -by Smt. Veena Kohli, Patron, AIWC : Smt. Veena Kohli : Smt. Rakesh Dhawan Mangal Murti- Our Hope in the Pandemic ......... 19 -by Smt. Rekha A. Sali AIWC has Consultative Status with UN Observer's Status with UNFCCC Report of Four Zonal Webinars:All India Permanent Representatives : Smt. Sudha Acharya and Women’s Conference `CAUSE PARTNER’ Smt. Seema Upleker (ECOSOC) (UNICEF) of National Foundation for Communal AIWC has affiliation with International Harmony. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Baroda Archives - Southern Circle , Vadodara Unpublished (Huzur Political Office) 1

BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Baroda Archives - Southern Circle , Vadodara Unpublished (Huzur Political Office) 1. Section No - 1, General Dafter No. 1, File Nos. 1 to 8 2. Section No - 11, General Dafter No - 16, File Nos. 1 to 13 3. Section No - 12, General Dafter No - 19, File No - 1 4. Section No - 13, General Dafter No - 20, File Nos - 1 to 6 - A 5. Section No - 14, General Dafter No - 2, File No - 1 6. Section No - 16, General Dafter No - 10, File Nos - 1 to 19 7. Section No - 38, General Dafter No - 8, File Nos - 1 to 8 - B 8. Section No - 65, General Dafter No - 112, File No - 11 9. Section No - 67, General Dafter No - 117, File Nos - 30 to 35 10. Section No.73, General Dafter No. 456, File Nos - 1 to 6 - A 11. Section No - 75, General Dafter No - 457, File No - 1 12. Section No - 77, General Dafter No - 461, File Nos - 11 & 12 13. Section No - 78, General Daft er No - 463, File No - 1 14. Section No - 80, General Dafter No - 466, File Nos - 1 & 2 15. Section No - 88, General Dafter No - 440, File Nos - 1 to 4 16. Section No - 88, General Dafter No - 441, File No - 25 17. Section No - 103, General Dafter No - 143, File Nos - 37 & 38 18. Section No - 177, General Dafter No - 549, File Nos - 1 to 7 19. Section No177, General Dafter No - 550, File Nos - 4 to 16 20. Section No - 199, General Dafter No - 478, File Nos - 1 to 17 21. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Creative Space,Vol

Creative Space,Vol. 5, No. 2, Jan. 2018, pp. 59–70 Creative Space Journal homepage: https://cs.chitkara.edu.in/ Alternative Modernity of the Princely states- Evaluating the Architecture of Sayajirao Gaekwad of Baroda Niyati Jigyasu Chitkara School of Planning and Architecture, Chitkara University, Punjab Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: August 17, 2017 The first half of the 20th century was a turning point in the history of India with provincial rulers Revised: October 09, 2017 making significant development that had positive contribution and lasting influence on India’s growth. Accepted: November 21, 2017 They served as architects, influencing not only the socio-cultural and economic growth but also the development of urban built form. Sayajirao Gaekwad III was the Maharaja of Baroda State from 1875 Published online: January 01, 2018 to 1939, and is notably remembered for his reforms. His pursuit for education led to establishment of Maharaja Sayajirao University and the Central Library that are unique examples of Architecture and structural systems. He brought many known architects from around the world to Baroda including Keywords: Major Charles Mant, Robert Chrisholm and Charles Frederick Stevens. The proposals of the urban Asian modernity, Modernist vision, Reforms, planner Patrick Geddes led to vital changes in the urban form of the core city area. Architecture New materials and technology introduced by these architects such as use of Belgium glass in the flooring of the central library for introducing natural light were revolutionary for that period. Sayajirao’s vision for water works, legal systems, market enterprises have all been translated into unique architectural heritage of the 20th century which signifies innovations that had a lasting influence on the city’s social, economic, administrative structure as well as built form of the city and its architecture. -

Domestic Labour Relations in India Vulnerability and Gendered Life Courses in Jaipur

Domestic labour relations in India Vulnerability and gendered life courses in Jaipur Päivi Mattila Interkont Books 19 Helsinki 2011 Domestic labour relations in India Vulnerability and gendered life courses in Jaipur Päivi Mattila Doctoral Dissertation To be presented for public examination with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences in the Small Festive Hall, Main Building of the University of Helsinki on Saturday, October 8, 2011 at 10 a.m. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Social Sciences Department of Political and Economic Studies, Development Studies Interkont Books 19 opponent Dr. Bipasha Baruah, Associate Professor International Studies, California State University, Long Beach pre-examiners Dr. Bipasha Baruah, Associate Professor International Studies, California State University, Long Beach Adjunct Professor Raija Julkunen University of Jyväskylä supervisors Adjunct Professor Anna Rotkirch University of Helsinki Professor Sirpa Tenhunen Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Helsinki copyright Päivi Mattila published by Institute of Development Studies University of Helsinki, Finland ISSN 0359-307X (Interkont Books 19) ISBN 978-952-10-7247-5 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-7248-2 (PDF; http://e-thesis.helsinki.fi) graphic design Miina Blot | Livadia printed by Unigrafia, Helsinki 2011 CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgements iii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Research task and relevance 2 1.2 The scope and scale of paid domestic work in India 7 From colonial times to contemporary practices 7 Regulation of domestic work 11 Gender -

A Time Line of the Global History of Esotericism with Emphasis for Yoga Science on the West Since the European Renaissance

A Time Line of the Global History of Esotericism With Emphasis for Yoga Science on the West since the European Renaissance Scott Virden Anderson1 – http://www.yogascienceproject.org Email: [email protected] Draft 5/25/08 This is incomplete, a work in progress, a snapshot as of the draft date. To take it any further would consume more time that I have right now, so I’m setting it aside for the moment and posting this version as is. Note especially that the most recent part of the story is not well covered here and you’ll find only a few entries for the 20th Century (and there is much more to the story in the 19th Century as well) – interested readers can get a good feel for this more recent period of esotericist history by consulting just three books: Fields 1981,2 Hanegraaff 1998,3 and De Michelis 2004.4 Fields gives a good overview of Buddhism’s journey to the West since the 18th Century, Hanegraaff tells the story of the Western esotericisms that were “here to begin with,” and De Michelis recounts how “Modern Yoga” came to the West already “well predigested” for Westerners by Anglicized Indian Yogis themselves. My feeling is that at this point esotericism is best thought of as a global phenomenon. However, some scholars feel this approach is overly broad. Of particular importance for my Yoga Science project is the modern period beginning with the European Renaissance – since the notions of “science” first arose and came into contact with the older traditions of esotericism only in these past 800 years. -

Dadabhai Naoroji

UNIT – IV POLITICAL THINKERS DADABHAI NAOROJI Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917) also known as the "Grand Old Man of India" and "official Ambassador of India" was an Indian Parsi scholar, trader and politician who was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Asian to be a British MP, notwithstanding the Anglo- Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption after nine months. Naoroji was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress. His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India brought attention to the Indian wealth drain into Britain. In it he explained his wealth drain theory. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov. Dadabhai Naoroji's works in the congress are praiseworthy. In 1886, 1893, and 1906, i.e., thrice was he elected as the president of INC. In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations. India Post depicted Naoroji on stamps in 1963, 1997 and 2017. Contents 1Life and career 2Naoroji's drain theory and poverty 3Views and legacy 4Works Life and career Naoroji was born in Navsari into a Gujarati-speaking Parsi family, and educated at the Elphinstone Institute School.[7] He was patronised by the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and started his career life as Dewan (Minister) to the Maharaja in 1874. Being an Athornan (ordained priest), Naoroji founded the Rahnumai Mazdayasan Sabha (Guides on the Mazdayasne Path) on 1 August 1851 to restore the Zoroastrian religion to its original purity and simplicity. -

Geo-Social Structure of India and Dr. Ambedker

P: ISSN NO.: 2394-0344 E: ISSN NO.: 2455 - 0817 Vol-III * Issue- I* June - 2016 Geo-Social Structure of India and Dr. Ambedker Abstract Indian jurist, economist, politician and social reformer Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, popularly known as Babasaheb, was inspired the Dalit Buddhist movement and campaigned against social discrimination against Untouchables, while also supporting the rights of women and labour. He was Independent India's first law minister and the principal architect of the Constitution of India. His later life was marked by his political activities; he became involved in campaigning and negotiations for India's independence, publishing journals advocating political rights and social freedom for lower strata of the society and contributing significantly to the establishment of the state of India. In 1956 he converted to Buddhism, initiating mass conversions. Ambedkar's legacy includes numerous memorials and depictions in popular culture. Ambedkar was born into a poor low Mahar caste, which were treated as untouchables and subjected to socio-economic discrimination. Ambedkar's ancestors had long worked for the army of the British East India Company, and his father served in the British Indian Army at the Mhow cantonment. Although they attended school, Ambedkar and other untouchable children were segregated and given little attention or help by teachers. They were not allowed to sit inside the class. Keywords: Buddhist, Jurist, Untouchables, Second-Rate, Precepts, South borouth, Mooknayak, Bahishkrit, Poona Pact, Segregated, Conversion Introduction Ambedkar was born on 14 April 1891 in the town and military cantonment of Mhow in the Central Provinces (now in Madhya Pradesh ) . He was the 14th and last child of Ramji Maloji Sakpal, a ranked army officer at the post of Subedar and Bhimabai Murbadkar Sakpal. -

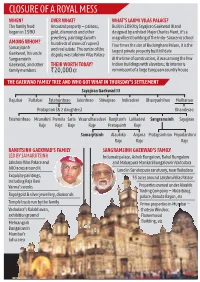

Closure of a Royal Mess

CLOSURE OF A ROYAL MESS WHEN? OVER WHAT? WHAT’S LAXMI VILAS PALACE? The family feud Ancestral property — palaces, Built in 1890 by Sayajirao Gaekwad III and began in 1990 gold, diamonds and other designed by architectMajorCharles Mant, it’s a jewellery, paintings (worth magnificent building of the Indo-Saracenic school AMONG WHOM? hundreds of crores of rupees) Samarjitsinh Four times the size of Buckingham Palace, it is the and real estate. The centre of the largest private property built till date Gaekwad, his uncle dispute was Lakshmi Vilas Palace Sangramsinh At the time of construction, it was among the few Gaekwad, and other THEIR WORTH TODAY? Indian buildings with elevators; its interior is family members ~20,000 cr reminiscent of a large European country house THE GAEKWAD FAMILY TREE AND WHO GOT WHAT IN THURSDAY’S SETTLEMENT Sayajirao Gaekwad III Bajubai Putlabai Fatehsinhrao Jaisinhrao Shivajirao Indiradevi Dhairyashilrao Malharrao Pratapsinh (& 2 daughters) Khanderao Fatehsinhrao Mrunalini Premila Sarla Vasundharadevi Ranjitsinh Lalitadevi Sangramsinh Sayajirao Raje Raje Raje Raje Pratapsinh Raje Samarjitsinh Alaukika Anjana Pratapsinhrao Priyadarshini Raje Raje Raje RANJITSINH GAEKWAD'S FAMILY SANGRAMSINH GAEKWAD’S FAMILY LED BY SAMARJITSINH Indumati palace, Ashok Bungalow, Bakul Bungalow Lakshmi Vilas Palace and and Makarpura Mankari Bungalow in Vadodara 600 acres around it Land in Sundarpura sanctuary, near Vadodara Exquisite paintings, 55 acres around Lakshmi Vilas Palace including Raja Ravi Varma’s works Properties owned underAlaukik Trading Company — Nazarbaug Royal gold & silver jewellery, diamonds palace, Baroda Rayon, etc Temple trusts run by the family Prime properties in Mumbai — Vadodara’s Kalabhavan, Chateau Windsor, exhibition ground Flowermead Mehrangarh Building, etc Bungalow in Mumbai’s Juhu area.