Changing Practices of Meat Consumption Among Hindus in a North Indian Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

NAVRATRI 2018 ITA Invites You for Garba and Raas at Navratri

NAVRATRI 2018 ITA invites you for Garba and Raas at Navratri 2018! Dates and Venues Oct 10, 11, 15, 16, 17 & 18 : 7.30 pm - 11 pm @ICC of South Jersey Oct 14 : 7.30 pm - 11 pm @Regal Banquet Hall, 1444 Rt. 73, Pennsauken Oct 12, 20 : 7.30 pm - 12 am @Eastern H.S, 1401 Laurel Oak Rd, Voorhees Oct 13, 7.30 pm-11 pm @Moorestown H.S, 350 Bridgeboro Rd. Moorestown October 20 as Shard Purnima Garaba Celebration Pricing Free Admission for all on Monday October 15 Children 6 & under - Free College Student Special on October 20th - $5 (w/ID) Pricing at door All ages (7 & above) : Sun to Thur: $5, Fri / Sat: $10 Season Pass Adults (18-64) : $45 At Door , $40 Online (Until Oct 5) Children (7-17) / Seniors (65+): $40 At Door , $35 Online (Until Oct 5) Online season pass can be purchased until October 5th at https://www.indiatemple.org/navratri-ticket.php ********************************************************************************************* Ravan Dahan ITA Dussehra Festival on Friday October 19th 2018 from 6—10pm at ICC ITA celebrates Dussehra on Friday October 19th at 6 pm at the ICC. There will be a Musical Ramayana Play presented by Hindi USA students. Raavan Dahan Bigger and better. Food Fun for the whole family. For information contact Sangeeta Rashatwar 609-685-2755, Jagdeep Talwar 856-308-7870 Rashmi Julka 856- 873-6447 ********************************************************************************************* Spiritual Celebration Importance of Pitri-Paksha Shradha-Tarpan - Every year, an important period of 15 days (Pitru Paksha or Shraadh) is dedicated to the ancestors and forefathers. Pitru Paksha is considered perfect for performing Tarpan rituals. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

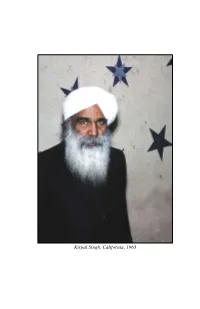

Kirpal-Singh-The-Jap-Ji.Pdf

INTRODUCTION Kirpal Singh, California, 1963 THE JAP JI INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI By Krpal Sngh “Man’s only duty is to be ever grateful to God for His innumerable gifts and blessings.” THE JAP JI about the translator . Krpal Sngh, a modern Sant n the drect lne of Guru Nanak, was born n 1894 n the Punjab n Inda (now part of Pakstan). Hs long lfe, saturated wth love for God and humanity, brought peace and fulfillment to approximately 120,000 dscples, scattered all over the world. He taught the natural way to find God while living; and His life was the embodment of Hs teachngs. He made three world tours, was Presdent of the World Fellowshp of Relgons for four- teen years, and convened the World Conference on Unty of Man n February 1974, attended by relgous, socal and poltcal leaders from all over the world. He ded on August 21, 1974, in his eighty-first year, stepping out of his body in full consciousness; His last words were of love for His dis- cples. Hs lfe bears eloquent testmony that the age of the prophets is not over; that it is still possible for human beings to find God and reflect His will. v v INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI The Message of Guru Nanak Literal Translation from the Original Punjabi Text with Introduction, Commentary, Notes, and a Biographical Study of Guru Nanak By Krpal Sngh A RUHANI SATSANG® BOOK RUHANI SATSANG DIVINE SCIENCE OF THE SOUL v v THE JAP JI I have written books without any copyright—no rights reserved — because it is a Gift of God, given by God, as much as sunlight; other gifts of God are also free. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

The Menstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 6-28-2017 The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity Jessie Norris Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Hindu Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Norris, Jessie, "The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity" (2017). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 694. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/694 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MENSTRUAL TABOO AND MODERN INDIAN IDENTITY A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of History and Degree Bachelor of Anthropology With Honors College Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Jessie Norris May 2017 **** CE/T Committee: Dr. Tamara Van Dyken Dr. Richard Weigel Sharon Leone 1 Copyright by Jessie Norris May 2017 2 I dedicate this thesis to my parents, Scott and Tami Norris, who have been unwavering in their support and faith in me throughout my education. Without them, this thesis would not have been possible. 3 Acknowledgements Dr. Tamara Van Dyken, Associate Professor of History at WKU, aided and counseled me during the completion of this project by acting as my Honors Capstone Advisor and a member of my CE/T committee. -

![UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8533/uzr-w-zvd-cv-e-wcvvu-848533.webp)

UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^

* + 7!4 8 5 ( 5 5 VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"$#$%T utqBVQWBuxy( (*+,(-'./ ,2,23 0,-1$( ,-./ 31<O62!12!&/$.& @ /< '% 261&$/$ 42/1$/%-; <3 .1<&/.1%.& 23&6 %2 /$!-< 26-$&/ 6& -1$6&$%6 -1& 4$&61 31&!$!12$6-624<@ &$6/$ 2!<12/$ 2>&-%&!$< $2</4.=?- 4216&4% 1=426&.&4>$'&=3&4& / - !$%&' (() *99 :& (2 & 0 1&0121'3'1& " # $ 2342/1$ 2342/1$ s the new I-T portal con- tepping up efforts to bring its Atinued to have glitches and Scitizens back home, India on remained unavailable for two Sunday airlifted 392 people, consecutive days, the Finance besides some Afghan politi- Ministry “summoned” Infosys cians, from Kabul to New Delhi. 2342/1$ MD and CEO Salil Parekh on They were evacuated in three Monday to explain to Finance different flights of the Indian mid the Afghanistan crisis Minister Nirmala Sitharaman Air Force (IAF) and Air India. Aand India’s ongoing evac- the reasons for the continued Some more flights are planned uation exercise following the snags even after over two in the days to come to safely Taliban takeover of the coun- months of the site’s launch. bring back stranded Indian cit- try, Union Housing and Urban However, just ahead of the izens from Afghanistan. Affairs Minister Hardeep Singh meeting with Sitharaman, A team of Indian officials Puri on Sunday cited the evac- Infosys late on Sunday night is now based in Kabul to assist uations from Afghanistan to said that emergency mainte- those Indians who want to back the controversial nance on the website had been return home. -

The Five Dacoits the Five Perversions of Mind from the Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and Others

The Five Dacoits The Five Perversions of Mind From The Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and others We are constantly beset by five foes - passion, anger, greed, worldly attachments, and vanity. All these must be mastered, brought under control. You can never do that entirely until you have the aid of the Guru and are in harmonic relations with the Sound Current. But you can begin now, and every effort will be a step on the way. (Baba Sawan Singh, Spiritual Gems, 339) Swami Ji has said that we should not hesitate to go all out to still the mind. We do not fully grasp that the mind takes everyone to his doom. It is like a thousand-faced snake, which is constantly with each being; it has a thousand different ways of destroying the person. The rich with riches, the poor with poverty, the orator with his fine speeches – it takes the weakness in each and plays upon it to destroy him. (Sant Kirpal Singh Ji) ruhanisatsangusa.org/serpent.htm Contents Page: 1. The Five Perversions of Mind, from The Path of the Masters, by Julian Johnson 2. Biography of Julian Johnson, from Wikipedia 3. Lust– Julian Johnson 5. The Case for Chastity, Parts 1 & 2 from Sat Sandesh 6. Sant Kirpal Singh Ji on Chastity 7. Hazur Baba Sawan Singh 8. Anger– Julian Johnson 10. Anger Quotes 11. Sant Kirpal Singh on Anger 12. Baba Sawan Singh, Jack Kornfield 13. Greed– Julian Johnson 14. Greed Quotes 15. -

Islam and Hinduism in the Eyes of Early European Travellers to India

Faraz Anjum * ISLAM AND HINDUISM IN THE EYES OF EARLY EUROPEAN TRAVELLERS TO INDIA Religion was an important identity marker in the early modern world. Whether in the East or the West, people distinguished themselves, among other things, with their adherence to a particular religion. In Europe, after Reformation in the early sixteenth century, the religious identities had got more sharpened and the Christian world was divided between the Catholics and the Protestants. Reformation strongly influenced the religious identities of European travellers and when they came into contact with the Indian religious beliefs and practices, they were “confronted with their own struggle for orientation. and the pattern for describing foreign religions was [thus] the pattern of differences between Catholicism and Protestantism.”1 While in India, Hinduism and Islam were the two dominant religions, though there were other minor religious denominations, like Budhists, Sikhs, and Parsees etc. The article is mainly concerned with the European representations of Islam and Hinduism in India. Focussing on the sixteenth and seventeenth century travel accounts of Europeans to India, it argues that these perceptions were strongly shaped by their belonging to Christian faith and their experiences of Europe. Most of European travellers considered Christianity as the only true religion and passed judgements on the Hindus and Muslims from a pure Christian perspective. They did not speak about them “without consigning them to eternal perdition.”2 This perception naturally resulted in their biased understanding of Indian religions. It is also a fact that some travellers were devoted missionaries and one of the principal motives of their travel to India was to convert the local population to Christianity. -

Basic Information on Shraddha Rituals

Basic Information on Shraddha Rituals Shraddha (Sanskrit) is a ceremony in honour and for the welfare of dead relatives, observed with great strictness at various fixed periods and on occasions of rejoicing as well as mourning by the surviving relatives. It is not a funeral ceremony, but an act of reverential homage to a deceased person performed by relatives, and is supposed to supply the dead with strengthening nutriment after the performance of the previous funeral ceremonies has endowed them with ethereal bodies. In Hinduism, the deceased relative is considered a preta (wandering ghost) until the first sraddha ceremony, when he attains a position among the spiritual pitris in their blissful abode. Shraddha Activities Shraddha rituals consist of following main activities – Vishwadeva Sthapana (ववेदेव थापना ) Pindadan ( प डदान ) Tarpan ( तपxण ) Feeding the Brahmin ( ामण भोज ) Pindadan is the offering of rice, cow’s milk, ghee, sugar and honey in form of Pinda (rounded heap of the offering) to ancestors. Pandadan should be done with whole-heartedness, devotion, sentiments and respect to the deceased soul to fulfil it. Tarpan is the offering of water mixed with black sesame (तल ), Barley ( ज ), Kusha grass ( कु शा ) and white flours. It is believed that ancestors are appeased by the process of Tarpan. Feeding the Brahmin is a must to complete the Shraddha ritual. Offering to the crows are also made before food is offered to the Brahmin. Pitru Paksha Period and Duration Pitru Paksha is the period of fifteen lunar days when Hindus pay homage to their ancestors, especially through food offerings. -

Religion and Geography

Park, C. (2004) Religion and geography. Chapter 17 in Hinnells, J. (ed) Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. London: Routledge RELIGION AND GEOGRAPHY Chris Park Lancaster University INTRODUCTION At first sight religion and geography have little in common with one another. Most people interested in the study of religion have little interest in the study of geography, and vice versa. So why include this chapter? The main reason is that some of the many interesting questions about how religion develops, spreads and impacts on people's lives are rooted in geographical factors (what happens where), and they can be studied from a geographical perspective. That few geographers have seized this challenge is puzzling, but it should not detract us from exploring some of the important themes. The central focus of this chapter is on space, place and location - where things happen, and why they happen there. The choice of what material to include and what to leave out, given the space available, is not an easy one. It has been guided mainly by the decision to illustrate the types of studies geographers have engaged in, particularly those which look at spatial patterns and distributions of religion, and at how these change through time. The real value of most geographical studies of religion in is describing spatial patterns, partly because these are often interesting in their own right but also because patterns often suggest processes and causes. Definitions It is important, at the outset, to try and define the two main terms we are using - geography and religion. What do we mean by 'geography'? Many different definitions have been offered in the past, but it will suit our purpose here to simply define geography as "the study of space and place, and of movements between places".