Microsoft Word Viewer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

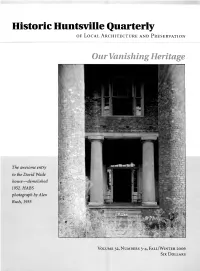

Historic Huntsville Quarterly of L O C a L a Rchitecture a N D P Reservation

Historic Huntsville Quarterly of L o c a l A rchitecture a n d P reservation Our Vanishing Heritage The awesome entry to the David Wade house— demolished 1952. HABS photograph by Alex Bush, 1935 V o l u m e 32, N u m b e r s 3 -4 , F a l l /W i n t e r 2006 Six D o l l a r s Historic Huntsville Quarterly o f L o c a l A rchitecture a n d P reservation Volum e 32, Num bers 3-4, Fall/W inter 2006 Contents 3 A Tradition of Research and Preservation The Elusive Past D ia n e E l l is From the Beginning L y n n J o n e s 10 Our Vanishing Heritage L in d a B a y e r A l l e n 20 The Second Madison County Courthouse Pa t r ic ia H . R y a n 28 The Horton-McCracken House L in d a B a y e r A l l e n 38 The David Wade House L in d a B a y e r A l l e n 46 The Burritt House P a t r ic ia H . R yan 54 The Demolition Continues T h e Q u a r t e r l y E d it o r s ISSN 1 0 74 -5 6 7X 2 | Our Vanishing Heritage Contributors and Editors Linda Bayer Allen has been researching and writing about Huntsville’s architectur al past intermittently for thirty years. -

As I Remember . .

Memories of My Parents Mildred Belle Tindell and Eugene Alexander Sharp (and a Few Other Folks) Compiled by Wayne Sharp Owners of the Homestead Owners from 1887 - Present Van Dela Cheek and Thomas Jefferson Tindell Family and Heirs Owners from 1839 - 1887 The Eliza B. Carr and John Jones Williamson Family Owners from 1818 - 1839 The Mary Hanby and Nathaniel Smith Family Owners from 1810 - 1818 Daniel Thomas Family Owners from 1788 - 1810 Thomas Polk (1788 Land Grant of 5,000 acres for services rendered during the Revolution) Deaths/Funerals known to have occurred in the home: David Williamson May 5 1777 – Feb 25 1870 John Jones Williamson Feb 11 1809 – May 2 1882 Elizabeth (Betsy) Rhyan Cheek (Mother of Van Della Cheek Tindell) 29 Mar 1816 - 22 May 1905 Thomas Jefferson Tindell May 2 1845 – April 16 1932 Van Della Cheek Tindell Oct 17 1852 – Dec 28 1935 ii Our Maury County Tennessee 1840s Farmhouse. iii iv Contents Page Homestead Previous Owners ii 1841 Homestead iii Homestead Construction Details iv Mildred Belle Tindell and Eugene Alexander Sharp 1 Bessie Pearl Thompson Davis 7 As I Remember (Stories and Tales of my Family while growing up) 15 Karen Michelle Sharp 37 Forward (As I was attempting to come up with a forward, this fell into my hands. Although she did not know it at the time, a great lady who worked with me at TSAC provided the material for this forward. I sent my "memories" musings to her and this was her response. Thank you Juanita Fann). Wayne, What? No Souse with crackers? No pickled pig feet? My father-in-law, Robert Hooper and I would sit down at the kitchen table and PIG out! Yum! (Pun definitely intended.) Liver? Tried that at the insistence of my mother-in-law; Never, again!!! Lard biscuits can't be beat; just add some milk gravy and sop it up! Butter Milk cornbread minus cracklings is the favorite bread for son Tony. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

The Cure — Wikipédia

The Cure — Wikipédia https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cure The Cure 1 The Cure [ðə ˈkjʊə(ɹ)] est un groupe de rock britannique, originaire de Crawley, dans le Sussex The Cure de l'Ouest, en Angleterre. Formé en 1976, le groupe comprend actuellement Robert Smith, Roger O'Donnell aux claviers, Simon Gallup à la basse, Reeves Gabrels à la guitare et Jason Cooper à la batterie. Robert Smith est la figure emblématique du groupe. Il en est le chanteur et le guitariste (il joue également de la basse ou des claviers), le parolier et le principal compositeur. Par ailleurs, il est le seul membre présent depuis l'origine du groupe. The Cure, à Singapour le 1er août 2007. Associé au mouvement new wave, The Cure a Informations générales développé un son qui lui est propre, aux ambiances 2, 3 Pays d'origine Royaume-Uni tour à tour mélancoliques, rock, pop, gothiques Genre musical Cold wave, new wave, et psychédéliques, créant de forts contrastes, où la post-punk, rock alternatif, basse est mise en avant et n’est pas seulement un rock gothique instrument d’accompagnement. Elle est, Années actives Depuis 1976 notamment en raison du jeu particulier de Simon Gallup une composante essentielle de la musique de Labels Fiction Records, Geffen The Cure. L'utilisation conjointe d'une basse six Records cordes (souvent une Fender VI), au son Site officiel www.thecure.com caractéristique, très souvent utilisée dans les motifs (http://www.thecure.com) mélodiques, contribue pour beaucoup à la signature Composition du groupe sonore si singulière du groupe. Membres Robert Smith Cette identité musicale, ainsi qu'une identité Simon Gallup visuelle véhiculée par des clips, contribuent à la Roger O'Donnell popularité du groupe qui atteint son sommet dans Jason Cooper les années 1980. -

In This Issue... OUR CORE VALUES Hospitality Stewardship Creativity

December 2020 Employee Newsletter OUR CORE VALUES Hospitality Stewardship Creativity & Innovation Hard Work In this Issue... 2 In the Spotlight 3 Did You Know? 4 Birthdays 5 Anniversaries Our Core Values 6 In Action 6-7 Recreation & Parks 7-8 Public Safety 9-12 Human Resources Meeting the needs of The Villages community Residents is our primary objective. We join together to acknowledge and thank everyone for your hard work and efforts - you each have been a bright PURPOSE spot in what was a most challenging year. As we think back To provide and preserve the lifestyle of Florida’s on all those that have influenced our lives and remain in our Friendliest Hometown. memories, please hold close to your hearts those team mem- bers, family and friends that we have lost. VISION To be respected as the most With sincere appreciation, and good wishes for a happy, responsive healthy New Year! and responsible Community Development The District Senior Management Team District. MISSION To provide responsible and Pictured left to right, top to bottom: accountable Richard Baier, District Manager; Kenny Blocker, Deputy District Manager; Carrie Duckett, Assistant District public service that enhances Manager; Jennifer Farlow, District Clerk; Mark LaRock, Director, Purchasing; John Rohan, Director, Recre- and sustains ation & Parks; Anne Hochsprung, Director, Finance; Blair Bean, Director, DPM; Nehemiah Wolfe, Director, our community. Community Watch; Edmund Cain; Director, Public Safety; Mitchell Leininger, Director, Executive Golf Maintenance; Barbara Kays, Director, Budget; Deb Franklin, Director, Human Resources & Strategic Plan- ning; Tamara Hyder; Executive Assistant to Mr. Baier 1 IN THE SPOTLIGHT… Bruce Brown ~ Property Management ~ Assistant Director Where were you born & raised and went to school? I was born in Bayshore, New York (Long Island) but moved when I was about eight to Merrimack, New Hampshire. -

Horowitz Home Torn Down

FREE All it takes is to grab one! Presorted Standard US Postage Paid Permit No. 81 Cedar Springs, MI The Reaching around the world - www.cedarspringspost.comST Vol. XXVIII No.P 37 Thursday, September 17, 2015 Serving Northern Kent County and parts of Newaygo and Montcalm Counties Roller Horowitz home torn down New assisted living center to be built on coaster property By Judy Reed gas prices A house built in the early to sell his house at 426 days of Cedar Springs was Northland Drive for sever- demolished this week to al years, and it was bought make way for a new assist- in June by Retirement Liv- ed living and memory care ing Management, based in center. Lowell. Retired teacher Steve According to Cedar Springs Horowitz had been trying Museum Director Sharon Jett, Post photo by L. Allen. Photo from City of Cedar Springs data base. Gas prices plummeted This home at 426 Northland Drive, formerly owned by Steve Horowitz, was torn down this week. Monday and Tuesday to as Horowitz was hav- According to the Cedar in 1858, he came to Mich- low as $2.04 a gallon, then ing a back room Springs Story, by Sue Harri- igan with his brother, Capt. rebounded sharply to $2.39 renovated several son and the late Donna De- W.P. Andrus. They stopped per gallon on Wednesday. years ago, when a Jonge, the home was built in Kalamazoo, where Sam Wednesday was the switch- beam was discov- by Sam Andrus, who lived went to school, and he went over from summer to winter ered that had “built there for many years. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2004 5,000+ Top Sellers

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2004 5,000+ TOP SELLERS COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, Videos, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2004 5,000+ titles listing are all of U.K. manufactured (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. 695 10,000 MANIACS campfire songs Double B9 14.00 713 ALARM in the poppy fields X4 12.00 793 ASHER D. street sibling X2 12.80 866 10,000 MANIACS time capsule DVD X1 13.70 859 ALARM live in the poppy fields CD/DVD X1 13.70 803 ASIA aqua *** A5 7.50 874 12 STONES potters field B2 10.50 707 ALARM raw E8 7.50 776 ASIA arena *** A5 7.50 891 13 SENSES the invitation B2 10.50 706 ALARM standards E8 7.50 819 ASIA aria A5 7.50 795 13 th FLOOR ELEVATORS bull of the woods A5 7.50 731 ALARM, THE eye of the hurricane *** E8 7.50 809 ASIA silent nation R4 13.40 932 13 TH FLOOR ELEVATORS going up-very best of A5 7.50 750 ALARM, THE in the poppyfields X3 -

The Lady of Little Fishing CONSTANCE FENIMORE WOOLSON

The Library of America • Story of the Week From Constance Fenimore Woolson: Collected Stories (LOA, 2020), pages 118–39. First published in the September 1874 issue of The Atlantic Monthly and subsequently reprinted in Castle Nowhere: Lake-Country Sketches (1875). The Lady of Little Fishing CONSTANCE FENIMORE WOOLSON t was an island in Lake Superior . I I beached my canoe there about four o’clock in the af- ternoon, for the wind was against me and a high sea running . The late summer of 1850, and I was coasting along the south shore of the great lake, hunting, fishing, and camping on the beach, under the delusion that in that way I was living “close to the great heart of nature,” — whatever that may mean . Lord Bacon got up the phrase; I suppose he knew . Pulling the boat high and dry on the sand with the comfortable reflection that here were no tides to disturb her with their goings- out and comings- in, I strolled through the woods on a tour of explo- ration, expecting to find bluebells, Indian pipes, juniper rings, perhaps a few agates along-shore, possibly a bird or two for company . I found a town . It was deserted; but none the less a town, with three streets, residences, a meeting- house, gardens, a little park, and an at- tempt at a fountain . Ruins are rare in the New World; I took off my hat . “Hail, homes of the past!” I said . (I cultivated the habit of thinking aloud when I was living close to the great heart of nature .) “A human voice resounds through your arches” (there were no arches, — logs won’t arch; but never mind) “once more, a human hand touches your venerable walls, a human foot presses your deserted hearth- stones ”. -

Las Vegas Optic, 03-21-1913 the Optic Publishing Co

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 3-21-1913 Las Vegas Optic, 03-21-1913 The Optic Publishing Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news Recommended Citation The Optic Publishing Co.. "Las Vegas Optic, 03-21-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news/1950 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. mtorical iociit n. Z3 r i pj Daily Maxim Weather Forecast U) U Li Read the Storm Story j Tonight aiid Saturday w vLp u Then a Cloudy; Tempera- and Dig j Cave ture Unchanged AS) Nice j EXCLUSIVE ASSOCIATED PRE68 LEASED' WIRE TELEGRAPH SERVICE i VOL. XXXIV. NO. 112. LAS VEGAS DAilLY OP'C, FRIDAY, MARCH 21, 1913. CITY EDtTION Several houses were Diown down women and children ce removed from in Gibbsland, a town In Bienville GONZALES KILLED the place. Automobiles continue to SHALL BONDS BE ISSUED FOR THE TERRIHGSTQRHSWEEPSSUUraERN parish,' and several thousand dollars' hurry the to the bor- property damage was done. The der, at Bisbee and Douglas, and before house of Joe Randall in Gibbsland IV THRIFT A the time of the threatened attack all car- women will OF A SUITABLE SITE STATES LEAVING TRAil OF DEATH; was hloyn from its foundation, II I1IUUI fl and children have been PURCHASE ried through the air several hundred removed. -

Sadegh-Vaziri Dissertation

IRANIAN DOCUMENTARY FILM CULTURE: CINEMA, SOCIETY, AND POWER 1997-2014 ____________________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ____________________________________________________________________________________ by Persheng Sadegh-Vaziri December 2015 Examining Committee Members: Patrick M. Murphy, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Roderick Coover, Film Media Arts Naomi Schiller, Anthropology & Archaeology, Brooklyn College Hamid Naficy, Radio-TV-Film, Northwestern University Nora M. Alter, External Member, Film Media Arts © Copyright 2015 by Persheng Sadegh-Vaziri All Rights Reserved ! ii! ABSTRACT Iranian documentary filmmakers negotiate their relationship with power centers every step of the way in order to open creative spaces and make films. This dissertation covers their professional activities and their films, with particular attention to 1997 to 2014, which has been a period of tremendous expansion. Despite the many restrictions on freedom of expression in Iran, especially between 2009 and 2013, after the uprising against dubious election practices, documentary filmmakers continued to organize, remained active, and produced films and distributed them. In this dissertation I explore how they engaged with different centers of power in order to create films that are relevant -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22 1975 - Notes On A Conditional Form - White Vinyl £ 26 1975, The - A BRIEF INQUIRY INTO ONLINE RELATIONSHIPS (2 LP) £ 27 2 CHAINZ - Rap Or Go To The League £ 18 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15 50 CENT - Best Of (2 LP) £ 24 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38 ABBA - Super Trouper £ 20 ABBA - Voulez-Vous £ 24 AC/DC - If You Want Blood You've Got It £ 22 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20 AC/DC - Paradise Theater Boston August 21st 1978 (Blue Vinyl) £ 16 AC/DC - Power Up - Red Vinyl £ 31 AC/DC - Power Up - Yellow Vinyl £ 31 AC/DC - Powerage £ 23 AC/DC - The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20 AC/DC Back in Black £ 23 Adele - 21 £ 19 Aerosmith - Done With Mirrors £ 25 AGNES OBEL - Myopia £ 25 Air - Moon Safari £ 26 Air - Talkie Walkie £ 20 AKERCOCKE - Renaissance In Extremis £ 19 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 20 ALANIS MORISSETTE - Jagged Little Pill Acoustic (2 LP) £ 30 ALANIS MORISSETTE - Such Pretty Forks In The Road £ 20 ALESSIA CARA - The Pains Of Growing £ 13 ALICE COOPER - Live From The Apollo (RSD 2020) £ 39 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21 ALICE IN CHAINS - Junkhead (Rare Tracks & TV Appearances) £ 25 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17 ALICE IN CHAINS - Live In Oakland October 8th 1992 (Green Vinyl) £ 16 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16 Altered Images - Greatest Hits £ 20 AMEDEO MINGHI / PIERO MONTANARI / ROBERTO CONRADO - Climax £ 14 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20 ANATHEMA - A Sort Of Homecoming £ 22 ANATHEMA - Eternity £ 20 Andrew W.K.