Postmodern Theory and the Choreography of Michael Clark Rachel Mathews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Thesis Re-Imagining Contemporary Choreography

Master Thesis Re-imagining Contemporary Choreography: Exploring choreographic practices in the post-moving era NAME: ELENA NOVAKOVITS STUDENT NUMBER: 4086856 Supervisor: Laura Karreman Second reader: Chiel Kattenbelt Master Contemporary Theatre, Dance and Dramaturgy Utrecht University August 2018 1 Abstract Focusing on the European dance scene after the mid-1990s a great emergence of dance practitioners redefined what dance could be by enlarging their creative methods, tools and objects. The established incessant movement was no longer considered to be the central element of composition. Similar artistic strategies still prevail up to the present, where the boundaries seem to be expanding ever more. Stimulated by this, in my thesis I look at the latest choreographic practices and their implications on a post-moving era. Drawing on André Lepecki’s Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement (2006), Efrosini’s Protopapa PhD “Possibilising dance: a space for thinking in choreography” (2009) and Bojana Cvejić’s Choreographing Problems: Expressive Concepts in European Contemporary Dance and Performance (2015) I examine the expanded choreographic practices in the following choreographic works: 69 Positions (2014) by Mette Ingvartsen and Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine (2010) by Mette Edvardsen. My hypothesis is that Ingvartsen and Edvardsen’s performances are exemplary of these developments. On the performance analysis of these works, I have explored what they have presented as singular choreographic practices through their artistic strategies by activating specific tools and methods. The idea of ‘language choreography’ is discussed as a common place for both. In conclusion, my main aim has been to analyse and evaluate how contemporary choreography in this post-moving era has been redefined in these works and what the resulting implications are for making, performing and attending. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefihe Wikst

POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefihe Wikstrom Ofelia Jarl Ortega Samlingen Valeria Graziano • Samira Elagoz Ellen Soderhult Edgar Schmitz Manuel Scheiwiller Alina Popa Antonia Rohwetter & Max Wallenhorst Danjel Andersson : R - i I- " Mette Edvardsen Marten Spdngberg (Eds.) % POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefine Wikstrom Ofelia Jarl Ortega Samlingen Valeria Graziano Samira Elagoz Ellen Soderhult Edgar Schmitz Manuel Scheiwiller Alina Popa Antonia Rohwetter & Max Wallenhorst Danjel Andersson Mette Edvardsen Marten Spangberg (Eds.) Published by MDT 2017 Creative commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Edited by Danjel Andersson, Mette Edvarsdsen and Mirten Spingberg Designed by Jonas Williamson ISBN 978-91-983891-0-4 This book is supported by Cullbergbaletten and Life Long Burning, a cultural network, funded with support from the European Commission. CULLBERGBALETTEN Culture o BUNNTNG Contents Acknowledgement 9 Danjel Andersson I Had a Dream 13 Marten Spangberg Introduction 18 Alice Chauchat Generative Fictions, or How Dance May Teach Us Ethics 29 Ana Vujanovic A Late Night Theory of Post-Dance, a selfinterview 44 Andre Lepecki Choreography and Pornography 67 Jonathan Burrows Keynote address for the Postdance Conference in Stockholm 83 Bojana Cvejic Credo In Artem Imaginandi 101 Bojana Kunst Some Thoughts on the Labour of a Dancer 116 Charlotte Szasz Intersubjective -

Expressions of Form and Gesture in Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater, and Contemporary Dance Tonja Lara Van Helden University of Colorado at Boulder, [email protected]

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Comparative Literature Dissertations Spring 1-1-2012 Expressions of Form and Gesture in Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater, and Contemporary Dance Tonja Lara van Helden University of Colorado at Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/coml_gradetds Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Dance Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation van Helden, Tonja Lara, "Expressions of Form and Gesture in Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater, and Contemporary Dance" (2012). Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations. Paper 10. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Comparative Literature at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Literature Graduate Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPRESSIONS OF FORM AND GESTURE IN AUSDRUCKSTANZ, TANZTHEATER, AND CONTEMPORARY DANCE by TONJA VAN HELDEN B.A., University of New Hampshire, 1998 M.A., University of Colorado, 2003 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Program of Comparative Literature 2012 This thesis entitled: Expressions Of Form And Gesture In Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater, And Contemporary Dance written by Tonja van Helden has been approved for the Comparative Literature Graduate -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

The Spectator As Mitreisender in the Tanztheater of Pina Bausch

DOCTORAL THESIS A Perplexing Pilgrimage: The Spectator as Mitreisender in the Tanztheater of Pina Bausch Campbell Daly, Janis Award date: 2009 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 A Perplexing Pilgrimage: The Spectator as Mitreisender in the Tanztheater of Pina Bausch By Janis Campbell Daly, BA (Hons), MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD School of Arts Roehampton University University of Surrey July 2009 Abstract Focusing on spectator issues and performative processes in postmodern dance performance, the thesis offers a new ecological approach for the analysis of dance based on the premiss that the spectator’s interactive role as Mitreisender or ‘fellow traveller’ in Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater is integral to the creation of the live experience and to a realisation of her work in performance. Centred on the multi- faceted role of Mitreisender as intrinsic to Bausch’s collaborative approach, the limited scope of phenomenological discourse to spectator-centred accounts highlights the need for a broader analytical approach to address the interactive dialectic between spectator, performer and their sensory environment and their physiological engagement in Bausch’s interrogative, exploratory processes. -

An American Perspective on Tanztheater Author(S): Susan Allene Manning Source: the Drama Review: TDR, Vol

An American Perspective on Tanztheater Author(s): Susan Allene Manning Source: The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Summer, 1986), pp. 57-79 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1145727 . Accessed: 24/08/2011 16:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Drama Review: TDR. http://www.jstor.org An American Perspective on Tanztheater Susan Allene Manning At a symposium of German and American modern dance held last fall at Goethe House New York, Anna Kisselgoff, chief dance critic for The New York Times, turned to Reinhild Hoffmann, director of the Tanz- theater Bremen, and asked in exasperation, "But why aren't you more interested in dance vocabularies?" Hoffmann did not answer but instead turned to Nina Wiener, a New York choreographer, and asked, "But why aren't you more interested in the social problems seen in a city like New York?" Weiner did not answer. This incomplete exchange-two questions that received no answers- summarizes the divergence between German and American modern dance today. -

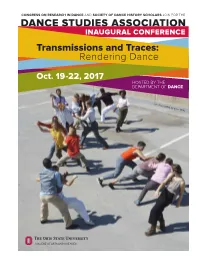

Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance

INAUGURAL CONFERENCE Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance Oct. 19-22, 2017 HOSTED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF DANCE Sel Fou! (2016) by Bebe Miller i MAKE YOUR MOVE GET YOUR MFA IN DANCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN We encourage deep engagement through the transformative experiences of dancing and dance making. Hone your creative voice and benefit from an extraordinary breadth of resources at a leading research university. Two-year MFA includes full tuition coverage, health insurance, and stipend. smtd.umich.edu/dance CORD program 2017.indd 1 ii 7/27/17 1:33 PM DEPARTMENT OF DANCE dance.osu.edu | (614) 292-7977 | NASD Accredited Congratulations CORD+SDHS on the merger into DSA PhD in Dance Studies MFA in Dance Emerging scholars motivated to Dance artists eager to commit to a study critical theory, history, and rigorous three-year program literature in dance THINKING BODIES / AGILE MINDS PhD, MFA, BFA, Minor Faculty Movement Practice, Performance, Improvisation Susan Hadley, Chair • Harmony Bench • Ann Sofie Choreography, Dance Film, Creative Technologies Clemmensen • Dave Covey • Melanye White Dixon Pedagogy, Movement Analysis Karen Eliot • Hannah Kosstrin • Crystal Michelle History, Theory, Literature Perkins • Susan Van Pelt Petry • Daniel Roberts Music, Production, Lighting Mitchell Rose • Eddie Taketa • Valarie Williams Norah Zuniga Shaw Application Deadline: November 15, 2017 iii DANCE STUDIES ASSOCIATION Thank You Dance Studies Association (DSA) We thank Hughes, Hubbard & Reed LLP would like to thank Volunteer for the professional and generous legal Lawyers for the Arts (NY) for the support they contributed to the merger of important services they provide to the Congress on Research in Dance and the artists and arts organizations. -

The Debaprasad Das Tradition: Reconsidering the Narrative of Classical Indian Odissi Dance History Paromita Kar a Dissertation S

THE DEBAPRASAD DAS TRADITION: RECONSIDERING THE NARRATIVE OF CLASSICAL INDIAN ODISSI DANCE HISTORY PAROMITA KAR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO DECEMBER 2013 @PAROMITA KAR, 2013 ii Abstract This dissertation is dedicated to theorizing the Debaprasad Das stylistic lineage of Indian classical Odissi dance. Odissi is one of the seven classical Indian dance forms recognized by the Indian government. Each of these dance forms underwent a twentieth century “revival” whereby it was codified and recontextualized from pre-existing ritualistic and popular movement practices to a performance art form suitable for the proscenium stage. The 1950s revival of Odissi dance in India ultimately led to four stylistic lineage branches of Odissi, each named after the corresponding founding pioneer of the tradition. I argue that the theorization of a dance lineage should be inclusive of the history of the lineage, its stylistic vestiges and philosophies as embodied through its aesthetic characteristics, as well as its interpretation, and transmission by present-day practitioners. In my theorization of the Debaprasad Das lineage of Odissi, I draw upon Pierre Bourdieu's theory of the habitus, and argue that Guru Debaprasad Das's vision of Odissi dance was informed by the socio-political backdrop of Oriya nationalism, in the context of which he choreographed, but also resisted the heavy emphasis on coastal Oriya culture of the Oriya nationalist movement. My methodology for the project has been ethnographic, supported by original archival research. -

ICTM B5.Indd

Department of Ethnomusicology, Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre in partnership with Klaipėda University, The Council for the Safeguarding of Ethnic Culture, The Klaipėda Ethnic Culture Center, and The Lithuanian Ethnic Culture Society 31st Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology 12th-18th July, 2021 Klaipėda, Lithuania ABSTRACTS BOOKLET Department of Ethnomusicology, Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre in partnership with Klaipėda University, The Council for the Safeguarding of Ethnic Culture, The Klaipėda Ethnic Culture Center, and The Lithuanian Ethnic Culture Society 31st Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology 12th-18th July, 2021 Klaipėda, Lithuania ABSTRACTS BOOKLET Symposium is supported by The author of the carp used for the cover – a certified master of national heritage products Diana Lukošiūnaitė Layout Rokas Gelažius Introductory Words by Dr. Catherine Foley Chair ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology The year 2020 has been a memorable and unprecedented year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This pandemic has presented health, social, economic and pedagogi- cal challenges worldwide, which has included the cancellation or postponement of many events. This included the postponement of the 31st Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, which was due to have taken place in July 2020 in Klaipeda, Lithuania, but on public health advice, the Executive Committee made the decision to postpone the symposium to July 2021. With the prospect of COVID-19 vaccines being rolled out in different countries in early 2021, delegates were offered the opportunity to present either face-to-face presentations at the symposium in Klaipėda in July 2021 or online presentations. -

Gus Solomons Jr.: Analyzing the Dances of an Early Black Postmodernist

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-6-2021 Gus Solomons Jr.: Analyzing the Dances of an Early Black Postmodernist Zsuzsanna Orban CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/676 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Gus Solomons jr: Analyzing the Dances of an Early Black Postmodernist by Zsuzsanna Orban Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 December 13, 2020 Michael Lobel Date Thesis Sponsor December 17, 2020 Howard Singerman Date Second Reader ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Gus Solomons jr., who inspired this thesis and was kind enough to share his time and knowledge with me. Thank you to my advisor Professor Michael Lobel and Professor Howard Singerman for their valuable guidance and assistance. I would also like to thank the staff at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at the New York Public Library and the Merce Cunningham Trust for their diligent help. Finally, thank you to my parents and to my best friend Michelle Harmantzis for their love and support. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………………ii INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER ONE. Early Life and Training………………………………………………………3 Boston New York Merce Cunningham Dance Company CHAPTER TWO. -

Workshops & Research

WORKSHOPS & RESEARCH 19 JULY - 15 AUGUST 2015 Workshops in Contemporary Dance and Bodywork for all levels from beginners to professional dancers. Seven phases which can be attended independently from each other (each week- workshop: 1 class per day, each intensive-workshop: 2 classes per day) «impressions'15»: 19 July ! Week1: 20 - 24 July Intensive1: 25 + 26 July Week2: 27 July - 31 July ! Intensive2: 01 + 02 August! Week3: 03 - 07 August! Intensive3: 08 + 09 August! Week4: 19 - 14 August ! «expressions'15»: 15 August Index 3 Artists listed by departments 4 - 134 All workshop descriptions listed by artists 135 - 146 All Field Project descriptions listed by artists 146 - 148 Pro Series descriptions listed by artists 2 AMERICAN EUROPEAN CONTEMPORARY Conny Aitzetmueller | Kristina Alleyne | Sadé Alleyne | Amadour Btissame | Laura Arís | Iñaki Azpillaga | Susanne Bentley | Nicole Berndt-Caccivio | Andrea Boll | Bruno Caverna | Marta Coronado | Frey Faust | David Hernandez | Florentina Holzinger | Peter Jasko | German Jauregui | Kira Kirsch | Clint Lutes | Simon Mayer | Rasmus Ölme | Sabine Parzer | Francesco Scavetta | Rakesh Sukesh | Samantha Van Wissen | Angélique Willkie | Hagit Yakira | David Zambrano IMPROVISATION Eleanor Bauer | Susanne Bentley | David Bloom | Alice Chauchat | DD Dorvillier | Defne Erdur | Alix Eynaudi | Jared Gradinger | Miguel Gutierrez | Andrew de Lotbinière Harwood | David Hernandez | Keith Hennessy | Claudia Heu | Jassem Hindi | Inge Kaindlstorfer | Jennifer Lacey | Benoît Lachambre | Charmaine LeBlanc | Pia Lindy