Gus Solomons Jr.: Analyzing the Dances of an Early Black Postmodernist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course of Study for the Teaching of Music in the Junior High Schools of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1967 Course of study for the teaching of music in the junior high schools of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada Mary Helene Wadden The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wadden, Mary Helene, "Course of study for the teaching of music in the junior high schools of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada" (1967). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1926. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1926 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURSE OF STUDY FOR THE TEACHING OF MUSIC IN THE JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOLS OF LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA by Sister Mary Helene Wadden B. Mus. Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, 19^0 B. Ed, University of Alberta, 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1967 Approved by: A -{ILCaAJI/I( (P A —— Chairman, Board of Examiners De^, Graduate School m1 9 Date UMI Number: EP34854 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, wfiMe others may be from any type of computer printer. Tfie quality of this reproducthm Is dependent upon ttie quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, ootored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleodthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wiU be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to t>e removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at ttie upper left-tiand comer and continuing from left to rigtit in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have t>een reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higtier qualify 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any pfiotographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional ctiarge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMT CHILDREN'S DANCE: AN EXPLORATION THROUGH THE TECHNIQUES OF MERGE CUNNINGHAM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sharon L. Unrau, M.A., CM.A. The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Emeritus Philip Clark Professor Seymour Kleinman, Advisor Assistant Professor Fiona Travis UMI Number 9962456 Copyright 2000 by Unrau, Sharon Lynn All rights reserved. -

Donald Mckayle's Life in Dance

ey rn u In Jo Donald f McKayle’s i nite Life in Dance An exhibit in the Muriel Ansley Reynolds Gallery UC Irvine Main Library May - September 1998 Checklist prepared by Laura Clark Brown The UCI Libraries Irvine, California 1998 ey rn u In Jo Donald f i nite McKayle’s Life in Dance Donald McKayle, performer, teacher and choreographer. His dances em- body the deeply-felt passions of a true master. Rooted in the American experience, he has choreographed a body of work imbued with radiant optimism and poignancy. His appreciation of human wit and heroism in the face of pain and loss, and his faith in redemptive powers of love endow his dances with their originality and dramatic power. Donald McKayle has created a repertory of American dance that instructs the heart. -Inscription on Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival Award orld-renowned choreographer and UCI Professor of Dance Donald McKayle received the prestigious Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival WAward, “established to honor the great choreographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of our modern dance heritage,” in 1992. The “Sammy” was awarded to McKayle for a lifetime of performing, teaching and creating American modern dance, an “infinite journey” of both creativity and teaching. Infinite Journey is the title of a concert dance piece McKayle created in 1991 to honor the life of a former student; the title also befits McKayle’s own life. McKayle began his career in New York City, initially studying dance with the New Dance Group and later dancing professionally for noted choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Sophie Maslow, and Anna Sokolow. -

Night of 100 Solos: a Centennial Event

2019 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, BAM Board Chair President William I. Campbell and Nora Ann Wallace David Binder, BAM Board Vice Chairs Artistic Director Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event Choreography by Merce Cunningham BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Apr 16 at 7:30pm Running time: approx. 90 minutes, no intermission Presented without inter- Stager Patricia Lent mission, Events consist of Associate stager Jean Freebury excerpts of dances from the Music director John King repertory and new sequences Set designer Pat Steir arranged for the particular performance and place, Costume designers and builders Reid Bartelme & Harriet Jung with the possibility of several Lighting designer Christine Schallenberg separate activities happening Technical director Davison Scandrett at the same time. —Merce Cunningham Co-produced by Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Barbican London, UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance, and the Merce Cunningham Trust Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event is part of the Merce Cunningham Centennial. Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event is generously supported by a major grant from the Howard Gilman Foundation. 2019 Winter/Spring is programmed by Joseph V. Melillo. Season Sponsor: Leadership support for dance at BAM provided by The Harkness Foundation for Dance Major support for dance at BAM provided by The SHS Foundation Support for the Signature Artists Series provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation Night of 100 Solos DANCERS Kyle Abraham, Christian Allen, Mariah Anton -

Master Thesis Re-Imagining Contemporary Choreography

Master Thesis Re-imagining Contemporary Choreography: Exploring choreographic practices in the post-moving era NAME: ELENA NOVAKOVITS STUDENT NUMBER: 4086856 Supervisor: Laura Karreman Second reader: Chiel Kattenbelt Master Contemporary Theatre, Dance and Dramaturgy Utrecht University August 2018 1 Abstract Focusing on the European dance scene after the mid-1990s a great emergence of dance practitioners redefined what dance could be by enlarging their creative methods, tools and objects. The established incessant movement was no longer considered to be the central element of composition. Similar artistic strategies still prevail up to the present, where the boundaries seem to be expanding ever more. Stimulated by this, in my thesis I look at the latest choreographic practices and their implications on a post-moving era. Drawing on André Lepecki’s Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement (2006), Efrosini’s Protopapa PhD “Possibilising dance: a space for thinking in choreography” (2009) and Bojana Cvejić’s Choreographing Problems: Expressive Concepts in European Contemporary Dance and Performance (2015) I examine the expanded choreographic practices in the following choreographic works: 69 Positions (2014) by Mette Ingvartsen and Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine (2010) by Mette Edvardsen. My hypothesis is that Ingvartsen and Edvardsen’s performances are exemplary of these developments. On the performance analysis of these works, I have explored what they have presented as singular choreographic practices through their artistic strategies by activating specific tools and methods. The idea of ‘language choreography’ is discussed as a common place for both. In conclusion, my main aim has been to analyse and evaluate how contemporary choreography in this post-moving era has been redefined in these works and what the resulting implications are for making, performing and attending. -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Mitchell, Arthur, 1934-2018 Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Arthur Mitchell, Dates: October 5, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:21:20). Description: Abstract: Dancer, choreographer, and artistic director Arthur Mitchell (1934 - 2018 ) was a principal dancer for the New York City Ballet for fifteen years. In 1969, he co-founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the first African American classical ballet company and school. Mitchell was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 5, 2016, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_034 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Dancer, choreographer and artistic director Arthur Mitchell was born on March 27, 1934 in Harlem, New York to Arthur Mitchell, Sr. and Willie Hearns Mitchell. He attended the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan. In addition to academics, Mitchell was a member of the New Dance Group, the Choreographers Workshop, Donald McKayle and Company, and High School of Performing Arts’ Repertory Dance Company. After graduating from high school in 1952, Mitchell received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American Ballet. In 1954, Mitchell danced on Broadway in House of Flowers with Geoffrey Holder, Louis Johnson, Donald McKayle, Alvin Ailey and Pearl Bailey. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

June 7, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1039 IN RECOGNITION OF THE WOMEN’S H. Savage of Idaho, David Williams Simnick of She will forever remain an inspiration to DIVISION OF THE FORT WORTH Illinois, Martin Iran Turman, Jr. of Indiana, many who seek guidance in her wisdom and METROPOLITAN BLACK CHAM- Preston Scott Bates of Kentucky, Seth D. words. She was noted for her no nonsense BER OF COMMERCE Dixon also of Kentucky, Benjamin David approach to the way of life as stated here, Goodman of Maine, Jonathan M. Brookstone ‘‘Don’t be nervous, don’t be tired and above HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS of Maryland, Zachary Ryan Davis of Massa- all, don’t be bored. Those are the three de- OF TEXAS chusetts, Lauren Brenda Gabriell Hollier of stroyers of freedom’’. Her insight goes far be- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Michigan, Marvin Anthony Liddell also of yond dance and choreography, but into the Michigan, Christine C. DiLisio of Missouri, real human dilemma. It was stated that, ‘‘she Wednesday, June 7, 2006 Vernon Telford Smith IV of Montana, Victoria was speaking less about dance and more Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Elizabeth Gilbert of the Model United Nations about an area of equal concern: human recognize the contributions of the Women’s program, Eoghan Emmet Kelley of New rights’’. All those who knew her dignified heart Division of the Fort Worth Metropolitan Black Hampshire, Danielle C. Desaulniers of New of compassion could not help but follow her Chamber of Commerce in its support for the Jersey, Juan Carlo Sanchez of New Mexico, lead. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Glen Tetley: Contributions to the Development of Modern

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. GLEN TETLEY: CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN DANCE IN EUROPE 1962-1983 by Alyson R. Brokenshire submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Of American University In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Arts In Dance Dr. -

POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefihe Wikst

POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefihe Wikstrom Ofelia Jarl Ortega Samlingen Valeria Graziano • Samira Elagoz Ellen Soderhult Edgar Schmitz Manuel Scheiwiller Alina Popa Antonia Rohwetter & Max Wallenhorst Danjel Andersson : R - i I- " Mette Edvardsen Marten Spdngberg (Eds.) % POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefine Wikstrom Ofelia Jarl Ortega Samlingen Valeria Graziano Samira Elagoz Ellen Soderhult Edgar Schmitz Manuel Scheiwiller Alina Popa Antonia Rohwetter & Max Wallenhorst Danjel Andersson Mette Edvardsen Marten Spangberg (Eds.) Published by MDT 2017 Creative commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Edited by Danjel Andersson, Mette Edvarsdsen and Mirten Spingberg Designed by Jonas Williamson ISBN 978-91-983891-0-4 This book is supported by Cullbergbaletten and Life Long Burning, a cultural network, funded with support from the European Commission. CULLBERGBALETTEN Culture o BUNNTNG Contents Acknowledgement 9 Danjel Andersson I Had a Dream 13 Marten Spangberg Introduction 18 Alice Chauchat Generative Fictions, or How Dance May Teach Us Ethics 29 Ana Vujanovic A Late Night Theory of Post-Dance, a selfinterview 44 Andre Lepecki Choreography and Pornography 67 Jonathan Burrows Keynote address for the Postdance Conference in Stockholm 83 Bojana Cvejic Credo In Artem Imaginandi 101 Bojana Kunst Some Thoughts on the Labour of a Dancer 116 Charlotte Szasz Intersubjective -

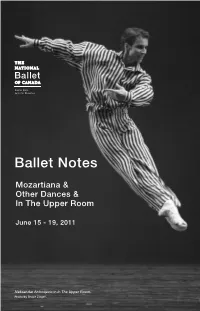

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes,