251 NERVA. September 18, A.D. 96 Saw Domitian Fall Victim to a Palace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

James E. Packer Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol

Report from Rome: The Imperial Fora, a Retrospective Author(s): James E. Packer Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Apr., 1997), pp. 307-330 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/506512 . Accessed: 16/01/2011 17:28 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aia. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org Report from Rome: The Imperial Fora, a Retrospective JAMES E. -

Roman Architecture with Professor Diana EE Kleiner Lecture 13

HSAR 252 - Roman Architecture with Professor Diana E. E. Kleiner Lecture 13 – The Prince and the Palace: Human Made Divine on the Palatine Hill 1. Title page with course logo. 2. Domus Aurea, Rome, sketch plan of park. Reproduced from Roman Imperial Architecture by John B. Ward-Perkins (1981), fig. 26. Courtesy of Yale University Press. 3. Portrait of Titus, from Herculaneum, now Naples, Archaeological Museum. Reproduced from Roman Sculpture by Diana E. E. Kleiner (1992), fig. 141. Portrait of Vespasian, Copenhagen. Reproduced from A History of Roman Art by Fred S. Kleiner (2007), fig. 9-4. 4. Roman Forum and Palatine Hill, aerial view. Credit: Google Earth. 5. Via Sacra, Rome. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. Arch of Titus, Rome, Via Sacra. Reproduced from Rome of the Caesars by Leonardo B. Dal Maso (1977), p. 45. 6. Arch of Titus, Rome, from side facing Roman Forum [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RomeArchofTitus02.jpg (Accessed February 24, 2009). 7. Arch of Titus, Rome, 18th-century painting [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:7_Rome_View_of_the_Arch_of_Titus.jpg (Accessed February 24, 2009). Arch of Titus, Rome, from side facing Colosseum. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 8. Arch of Titus, Rome, attic inscription and triumphal frieze. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 9. Arch of Titus, Rome, triumphal frieze, victory spandrels, and keystone. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 10. Arch of Titus, Rome, composite capital. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 11. Arch of Titus, Rome, triumph panel. Image Credit: Diana E. E. -

Rome - Vatikaan

ROME - VATIKAAN Als je het Sint Pietersplein opstapt besef je het plein en de basiliek helemaal niet zo maar in, het is misschien niet, maar je overschrijdt een staatsgrens. wel degelijk onafhankelijk, met een eigen staatshoofd, Sinds de "grote verzoening" immers van 1929, tussen regering, munt, politie, post, diplomatieke het (toen fascistische) Italië (van Mussolini) en de vertegenwoordiging. Vatikaanstad is trouwens iets Paus (Pius XI), ligt er in hartje Rome een groter dan dit complex: ook de grote basilieken (de onafhankelijke staat van 44 ha. groot en met + 1.000 Maria Maggiore, de Sint Jan van Lateranen en de Sint (bijna uitsluitend mannelijke!) bewoners. Het verdrag Paulus buiten de Muren), enkele palazzi in de stad van Lateranen sloot op die manier de periode af, (zoals bijv. de Cancelleria en de Propaganda Fide), waarin de Paus (sinds de inname van Rome door de het hospitaal "Bambino Gesù" op de Janiculus en het Garibaldisten in 1870) zich de "gevangene van het zomerverblijf van de Paus in Castelgandolfo, zijn Vatikaan" noemde. En om die nieuwe "openheid" ook "extraterritoriaal gebied" voor de Italiaanse staat. in het stadsbeeld duidelijk te maken werd toen de Het is goed om weten, maar als je niet onmiddellijk brede "Via della Conciliazione", de "Straat van de een afspraak hebt met de Paus of zijn administratie, Verzoening", aangelegd. maakt het eigenlijk niet veel uit. Alleen als je je post En ook al heeft het een vrij ouderwetse langs hier wil versturen, moet je weten dat je dan staatsstructuur (je kan het bezwaarlijk een moderne Vatikaanse zegels moet gebruiken, en dat je dat democratie noemen!), en geraak je d'er buiten het enkel hier kan! 1. -

Discovering a Roman Resort-Coat: the Litus Laurentinum and The

DISCOVERING A ROMAN RESORT-COAST: THE LITUS LAURENTINUM AND THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF 1 OTIUM* Nicholas Purcell St John's College, Oxford I. Introductory Otium - the concept of leisure, the elaborate social and cultural definer of the Roman elite away from its business of political and military power - is famous. We can see in Roman literary texts how the practice of otium patterned everyday experience, and how it was expressed in physical terms in the arrangement, on a large and on a small scale, of all aspects of Roman space. The texts likewise show that much of what we would regard as social life, and nearly all of what we think of as economic, belonged in the domain of otium. The complexities and ambiguities of this material have been much studied.2 Roman archaeology equally needs to be an archaeology of otium, but there has been little attempt to think systematically about what that might entail. Investigating the relationship between a social concept such as otium and the material culture that is the primary focus of archaeology must in the first place involve describing Roman culture in very broad terms. The density of explicit or implicit symbolic meaning, the organisation of space and time, degrees of hierarchy of value or prestige: it is at that level of generalisation that the archaeologist and the cultural historian will find the common denominators that enable them to share in the construction of explanations of Roman social phenomena. In this account, which is based on research into a particular locality, we shall have to limit ourselves to one of these possibilities. -

Recent Discoveries in the Forum, 1898-1904

Xil^A.: ORum 1898- 1:904 I^H^^Hyj|Oj|^yL|i|t I '^>^J:r_J~ rCimiR BADDELEY '•^V^^^' ^^^ i^. J^"A % LIBRARY RECENT DISCOVERIES IN THE FORUM Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/recentdiscoverieOObadd ^%p. ji^sa&i jI Demolishing the Houses Purchased by Mp. L. Piitlltps (1899) Frontispiece RECENT DISCOVERIES IN THE FORUM 1898-1904 BY AN EYE-WITNESS S:i^ CLAIR BADDELEY BEING A HANDBOOK FOR TRAVELLERS, WITH A MAP MADE FOR THIS WORK BY ORDER OF THE DIRECTOR OF THE EXCAVATIONS AND 45 ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON GEORGE ALLEN, 156, CHARING CROSS ROAD 1904 [All rights reserved] -. s* r \ i>< ^^ARY# r^ ¥ ^ y rci/O FEB 26 'X_> Printed by BALLANTYNK, HANSON <5r» Co. At the Ballantyne Press TO LIONEL PHILLIPS, Esq, IN MEMORY OF DAYS IN THE FORUM PREFATORY NOTE 1 HAVE heard life in the Forum likened unto ' La Citta Morte/ wherein the malign influences of ancient crimes rise up from the soil and evilly affect those who live upon the site. I have also heard it declared to be a place dangerous to physical health. It is with gratifi- cation, therefore, after living therein, both beneath it and above, as few can have done, for considerable portions of the last six years, that I can bring solid evidence to belie both accusations. They indeed would prove far more applicable if levelled at certain other august centres of Rome. For I find it necessary to return thanks here for valuable assistance given to me without hesitation and at all times, not only by my personal friend Comm. -

Constantine Triumphal Arch 313 AD Basilica of St. Peter Ca. 324

Constantine Triumphal Arch 313 AD Basilica of St. Peter ca. 324 ff. Old St. Peter’s: reconstruction of nave, plus shrine, transept and apse. Tetrarchs from Constantinople, now in Venice Constantine defeated the rival Augustus, Maxentius, at the Pons Mulvius or Milvian Bridge north of Rome, at a place called Saxa Rubra (“Red rocks”), after seeing a vision (“In hoc signo vinces”) before the battle that he eventually associated with the protection of the Christian God. Maxentius’s Special Forces (Equites Singulares) were defeated, many drowned; the corps was abolished and their barracks given to the Bishop of Rome for the Lateran basilica. To the Emperor Flavius Constantinus Maximus Father of the Fatherland the Senate and the Roman People Because with inspiration from the divine and the might of his intelligence Together with his army he took revenge by just arms on the tyrant And his following at one and the same time, Have dedicated this arch made proud by triumphs INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS TYRANNO Reconstruction of view of colossal Sol statue (Nero, Hadrian) seen through the Arch of Constantine (from E. Marlow in Art Bulletin) Lorsch, Germany: abbey gatehouse in the form of a triumphal arch, 9th c. St. Peter’s Basilicas: vaulted vs. columns with wooden roofs Central Hall of the Markets of Trajan Basilica of Maxentius, 3018-312, completed by Constantine after 313 Basilica of Maxentius: Vaulting in concrete Basilica of Maxentius, 3018-312, completed by Constantine after 313 Monolithic Corinthian column from the Basilica of Maxentius, removed in early 1600s by Pope Paul V and brought to the piazza in front of Santa Maria Maggiore Monolithic Corinthian column from the Basilica of Maxentius, removed in early 1600s by Pope Paul V and brought to the piazza in front of Santa Maria Maggiore BATHS OF DIOCLETIAN 298-306 AD Penn Station NY (McKim, Mead, and White) St. -

Architectural Spolia and Urban Transformation in Rome from the Fourth to the Thirteenth Century

Patrizio Pensabene Architectural Spolia and Urban Transformation in Rome from the Fourth to the Thirteenth Century Summary This paper is a historical outline of the practice of reuse in Rome between the th and th century AD. It comments on the relevance of the Arch of Constantine and the Basil- ica Lateranensis in creating a tradition of meanings and ways of the reuse. Moreover, the paper focuses on the government’s attitude towards the preservation of ancient edifices in the monumental center of Rome in the first half of the th century AD, although it has been established that the reuse of public edifices only became a normal practice starting in th century Rome. Between the th and th century the city was transformed into set- tlements connected to the principal groups of ruins. Then, with the Carolingian Age, the city achieved a new unity and several new, large-scale churches were created. These con- struction projects required systematic spoliation of existing marble. The city enlarged even more rapidly in the Romanesque period with the construction of a large basilica for which marble had to be sought in the periphery of the ancient city. At that time there existed a highly developed organization for spoliating and reworking ancient marble: the Cos- matesque Workshop. Keywords: Re-use; Rome; Arch of Constantine; Basilica Lateranensis; urban transforma- tion. Dieser Artikel bietet eine Übersicht über den Einsatz von Spolien in Rom zwischen dem . und dem . Jahrhundert n. Chr. Er zeigt auf, wie mit dem Konstantinsbogen und der Ba- silica Lateranensis eine Tradition von Bedeutungsbezügen und Strategien der Spolienver- wendung begründet wurde. -

Early Empire

APAH: Roman Art – Early Empire Octavian – Augustus “Pax Romana” – 150 years of peace Ease of travel, spread of ideas, construction & expansion Glory of Rome (pop. 1M) Greatest geographical extent [map] Imperial design – architecture/city-planning/urbanization Power of Rome Construction by government Promoted loyalty Roads (all roads lead to Rome) Communication, administration Apartments – insulae (45,000 in Rome) 5-story Stores on ground floor Some private toilets Public baths (w/ hot water) Public toilets Aqueducts Water-supplies Pont du Gard Supplied Nimes, France – 30 miles away 100 gallons h2o/person/day Architecture Barrel vaulting Half-cylindrical roof – deep arch Cross-barrel vaulting Intersection of two, barrel vaults Groin vault Cross-barrel vaulting of same height (successive) Pressure exerted at groin lines Colosseum – Flavian Amphitheater (70-80 AD) While the Colosseum stands, Rome stands; When the Colosseum falls, Rome falls; Theater – spectacles And when Rome, the world! Gladiatorial combat Opened in 80 AD with naval battle 50,000 seats Technical ingenuity Block & tackle Awning shades Entrances permit quick exit/entrance (gate number) Combines Roman arch/vault w/ Greek order & post/lintel Ascending orders: Tuscan, Ionic, Corinthian Roman arch order Covered concrete in travertine Forum Built by succeeding emperors Sign of care for Empire Building for the public Trajan (Marcus Ulpius Traianus) Height of Roman Empire Trajan’s Forum Completed in 112 AD Largest fora Architect Apollodorus of Damascus Latin / Greek libraries Exotic -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Trajan's Column

VIII TRAJAN'S COLUMN (figs 8.ó and Sruoms or Rou¡N ARCHITECTUnn often overlook ¡he tribes piled up like a mountaln of loot Column of Trajan, regarding it as the province of spe- more than a vehicle for cialists in sculpture, history or military matters. Every- Yet the Column is much column one's altention is mesmerized by the extraordinary sculpture. The simple formula of an honoriflc is of some 2oo metre long relief that winds around the shaft' A' masks a building - for that is what it - door, a vesúbule, document of exceptional artistic and historical impor- complexiry incorporating an entrance and a balcony in the form tance, it narrates the story of the Dacian .wars via a a chanber, a stair, windows succession of minutely detailed scenes' embracing not ofa capital. just the military action but a wide spectrum of related right, it has events.l Depictions of the horror of a mass Dacian Marcus Aur mimicked the archi- suicide are contrasted with legionaries tending crops or largely by the reließ, but others 'Works this theme include constructing buildings (fig. 8'¡); thus the propaganda of ,..t,rr. alone. related to London, dozens of war proclaimed the benefìts of a Roman peace' The Wren's Monument to the Fire of paper projects by such archi- pedestal too is covered by sculptural reließ, this time lighthouses, and reams of showing armorial trophies won from the opposing tects as Ledoux and Boullée'2 of the Forum of Trajan' showing che 8.r Forum of Trajan, Rome (ao ro5), view of Trajant Column 8.2 (aboue) Reconslruction to the Basilica Ulpia when seen from looking through the re-erected columns of the Basilica Lllpia ,.htìo.rrh'ip of the Column far end of the main court. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

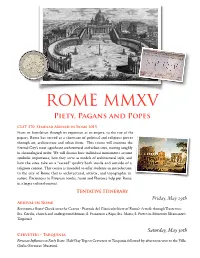

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

Ceremonial and Religious Functions of Roman Epideictic Genres

CEREMONIAL AND RELIGIOUS FUNCTIONS OF ROMAN EPIDEICTIC GENRES by MACEIO ILON LAUER (Under the Direction of Thomas Lessl) ABSTRACT This dissertation describes and analyzes the cultural, historical, and religious context surrounding three Roman epideictic texts in an effort to make broader theoretical arguments about Roman rhetoric. Each of the three case studies concentrate upon a distinctly Roman form of discourse and this dissertation argues that the ceremonial and ritual traditions attendant to these genres reflect the unique cultural salience of these texts and reveal the ways in which Roman epideictic developed independently of the Greek tradition. An initial overview of classical rhetorical theory reveals that scholarly treatments of epideictic rhetoric tend to emphasize the role played by Greek epideictic texts and typically dismiss or ignore the Roman epideictic tradition. More importantly, when studies of Roman epideictic forms are undertaken, they most often assume that the Roman forms derived the bulk of their topical, structural, and stylistic elements from earlier Greek antecedents. In fact, a full appreciation for the Roman texts requires a consideration of their own political and cultural context. The first case study investigates an early Contio of Cicero and argues that the Contio’s religious principles enabled the primarily deliberative speech form to assume an epideictic form. The second case study analyzes Augustus’ monumental Res Gestae and argues that this text marked a shift in the discursive conduct of Rome following the institution of the Principate. This shift was accompanied by a stronger emphasis on the spaces and rituals that amplified the message of the rhetor. The final study considers a Post-Augustan epideictic speech, Pliny’s Actio Gratiarum, and argues that this text reveals both the attendant ceremonial conduct of discourse during the second Century (C.E.), revealing the new relationship between rhetoric and the sociopolitical planning as well as the general themes of guiding the design of public space.