How the Houston Astros Are Winning Through Advanced Analytics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist 19TCUB VERSION1.Xls

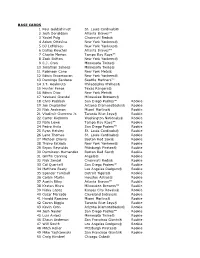

BASE CARDS 1 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 2 Josh Donaldson Atlanta Braves™ 3 Yasiel Puig Cincinnati Reds® 4 Adam Ottavino New York Yankees® 5 DJ LeMahieu New York Yankees® 6 Dallas Keuchel Atlanta Braves™ 7 Charlie Morton Tampa Bay Rays™ 8 Zack Britton New York Yankees® 9 C.J. Cron Minnesota Twins® 10 Jonathan Schoop Minnesota Twins® 11 Robinson Cano New York Mets® 12 Edwin Encarnacion New York Yankees® 13 Domingo Santana Seattle Mariners™ 14 J.T. Realmuto Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Hunter Pence Texas Rangers® 16 Edwin Diaz New York Mets® 17 Yasmani Grandal Milwaukee Brewers® 18 Chris Paddack San Diego Padres™ Rookie 19 Jon Duplantier Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie 20 Nick Anderson Miami Marlins® Rookie 21 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 22 Carter Kieboom Washington Nationals® Rookie 23 Nate Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 24 Pedro Avila San Diego Padres™ Rookie 25 Ryan Helsley St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 26 Lane Thomas St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 27 Michael Chavis Boston Red Sox® Rookie 28 Thairo Estrada New York Yankees® Rookie 29 Bryan Reynolds Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 30 Darwinzon Hernandez Boston Red Sox® Rookie 31 Griffin Canning Angels® Rookie 32 Nick Senzel Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 33 Cal Quantrill San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Matthew Beaty Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 35 Spencer Turnbull Detroit Tigers® Rookie 36 Corbin Martin Houston Astros® Rookie 37 Austin Riley Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 38 Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie 39 Nicky Lopez Kansas City Royals® Rookie 40 Oscar Mercado Cleveland Indians® Rookie -

The Astros' Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal Major League Baseball (MLB) fosters an extremely competitive environment. Tens of millions of dollars in salary (and endorsements) can hang in the balance, depending on whether a player performs well or poorly. Likewise, hundreds of millions of dollars of value are at stake for the owners as teams vie for World Series glory. Plus, fans, players and owners just want their team to win. And everyone hates to lose! It is no surprise, then, that the history of big-time baseball is dotted with cheating scandals ranging from the Black Sox scandal of 1919 (“Say it ain’t so, Joe!”), to Gaylord Perry’s spitter, to the corked bats of Albert Belle and Sammy Sosa, to the widespread use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Now, the Houston Astros have joined this inglorious list. Catchers signal to pitchers which type of pitch to throw, typically by holding down a certain number of fingers on their non-gloved hand between their legs as they crouch behind the plate. It is typically not as simple as just one finger for a fastball and two for a curve, but not a lot more complicated than that. In September 2016, an Astros intern named Derek Vigoa gave a PowerPoint presentation to general manager Jeff Luhnow that featured an Excel-based application that was programmed with an algorithm. The algorithm was designed to (and could) decode the pitching signs that opposing teams’ catchers flashed to their pitchers. The Astros called it “Codebreaker.” One Astros employee referred to the sign- stealing system that evolved as the “dark arts.”1 MLB rules allowed a runner standing on second base to steal signs and relay them to the batter, but the MLB rules strictly forbade using electronic means to decipher signs. -

Defensive Baseball – the Finer Details (By Position)

Defensive Baseball – The Finer Details (by position) Shortstop • Yells out, while signaling, the number of outs to these teammates and in this order – center fielder, left fielder, second baseman, third baseman, and pitcher • Likes to be the engineer of the double play (6-4-3) and takes pride in accurate throws to the second baseman • Wants every ground ball hit to him • Helps to “manage” the pitcher (motions to him to slow down or calm down, or directly tells him to do certain things, “hey, roll us a pair,” etc.) • Likes to read the ground ball up the middle with a runner on first, attack it, and initiate the (6U-3) double play • Takes great pride in his ability to cover the left-side of the infield from the third base hole to behind second base • Lives for the tag play at second on potential doubles to right or right-center, and the steal attempt with a left-handed hitter, and the daylight pick from the pitcher when the runner on second has taken too much of a lead • Understands and executes his role as the relay man on balls hit to deep left, left-center, and center field, making his presence known (giving a target with two hands up) and then always opens up to the glove side • Is vocal in taking the piggy-back trailer behind the second baseman on balls hit deep to right and right-center • Works on jumping to catch the high throw, coming off the bag, or diving to block an errant throw to prevent the overthrow from the second baseman, first baseman, pitcher or the catcher on a throw to second base • Asks for timeout and initiates a mound -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Defensive Responsibilities for the Second Baseman

DEFENSIVE RESPONSIBILITIES FOR THE SECOND BASEMAN Here are the defensive responsibilities at second base: • Cover first base on a bunt. Most bunt defenses have the first baseman crashing. The second baseman must get to the bag quickly and take the throw as if he were the first baseman. • Sprint to back up a play at first base. Get to the foul line behind first base as quickly as possible. • Communicate with the shortstop and the pitcher on the possibility of a comebacker. Either the Shortstop or the second baseman must know in advance who will take the throw from the pitcher on a comebacker (with a runner at first base.) • Change defensive positioning with a runner at first base. Play at double play depth; in three or four steps and over a few steps toward the bag. “Pinch the middle.” • Cover first base on a play at the plate with the first baseman the cutoff. • Be aware that you have priority on pop fouls behind first base. • Communicate with the shortstop with a runner on first base-“yes, yes-no, no.” It is important for the middle infielders to communicate with each other during the course of a game. This situation arises frequently in a game: a runner on first and the hitter hits a ground ball to either the second baseman or the shortstop. The off –infielder must let the fielder know where to throw the ball, either to first base or the easier play at second. If for instance, the ball is hit to the shortstop the second baseman must sprint to the bag in time to give him directions where to throw the ball. -

Team up Guidebook

Team Up Guidebook Bloomberg Associates 1 Resource and Operations Manual 1 Mayor Sylvester Turner of Houston, Texas, celebrates Team Up with Houston youth. Team Up leverages the power of sports to develop a city’s underserved youth, equipping them with the experience and motivation to pursue college while enhancing professional skills that can be applied to any career path. # TEAM UP 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Program Overview 4 History of the Program 5 Roadmap 6 The Operating Organization 7 1. Overview 7 2. Activities and Program Responsibilities 7 3. Essential Qualities 8 4. Budget 10 How To: Mayoral Office and City Government 11 1. Identify areas or programming that currently exist in local government 11 2. Present Team Up’s mission framed within city government’s mission 12 3. Emphasize the need for support and be straightforward on any specific asks 12 4. Follow up and share success; ask for increased support, if possible 13 How To: Schools and After-School Programs (ASPs) 14 1. Identifying possible schools and programs and pitch Team Up 14 2. Define expectation and inventory resources 15 3. Create the curriculum schedule with the sporting partner 15 4. Recruit students and gather baseline data 16 5. Discovery Days 16 6. Gathering impact data and report findings 17 How To: Sporting Partners 18 1. Recruiting local sporting partners 18 2. Define the scope of involvement and expectations 19 3. Evaluate the program and distribute materials 20 How To: Other Stakeholders and Sponsors 21 1. Identify a company that actively demonstrates community advocacy 21 2. Select a company that is common amongst current partners and future partners 21 3. -

Alumnigazette

ALUMNIGAZETTE NO. 4 VOL. I JAN 2018 MEXICO CITY ASF ALUMNI GAZETTE ALUMINIGAZETTE POLITICS Democrat Mark Rodríguez (‘01) makes city council in Annapolis, re- ceiving 610 votes in Ward 5. 1 MAJOR LEAGUES CONGRATULATIONS! An ASF BEAR brings the Houston Astros to the World Series. ¡Sí Alexis Fridman (‘01), Head of Production and Development at Lem- señor! Jeff Luhnow is Astro’s general manager and has changed the on Films, receives an Emmy Award for his TV Series Sr. Ávila. Such a game for this Texan team. big deal! ALUMNI HELP THE ART FAIR GO GREEN This year, ASF Alumni wanted to contribute in lowering the waste generated during the Art Fair. Robb Wright, ASF parent, donated 5000 green plastic reusable plates to ASF, which the Alumni distrib- uted to 14 vendors. In total, 2000 plates were used and reused during the Art Fair, greatly lessening the need for plastic and reducing our impact on the environment. Cafeteria staff, paid by the Alumni Association, cleaned each plate after it was used, and the student members of the ASF Sustainabil- ity Committee, under the leadership of Mr. José Alaniz, set shop at two recycling stations, where Mr. Alaniz helped Art Fair attendees to properly separate the trash and place the plates in containers to be washed. It was amazing to see how the whole community contributed in this effort, and we are happy to announce that we now have 5000 plates in stock so staff, clubs and committees don’t have to use disposable plastic plates during any school event. Seeing how successful this campaign was, next year we -

Stolen Signs to Stolen Wins?

Venkataraman and Bozzella 1 Devan Venkataraman & Nathaniel Bozzella EC 107 Empirical Project Sergio Turner 12/20/20 Stolen Signs to Stolen Wins? The Trash Can Banging Scandal Heard ‘Round the World Question To what extent, and in what ways, was the Houston Astros cheating scandal in the 2017 season effective in improving team performance? Introduction For the majority of the 2010’s, the Houston Astros were a very middle of the pack team. From 2010-2014, the team did not finish higher than 4th in their division. For most of their history, the Houston Astros participated in the National League Central Division, up until the 2013 season. Since the 2013 season, the Astros have competed in the American League West Division, where they have seen much more success. In 2011, the Astros, one of the worst teams in baseball with a record of 56-106, were sold to Jim Crane where he moved on from ex-GM Ed Wade, and hired Jeff Luhnow two days after the sale. While Ed Wade made some good decisions: debuting Jose Altuve in the 2011 season and drafting George Springer in the 2011 draft, his overall performance was not satisfactory for the new owner. The new GM, Jeff Luhnow, made some notable decisions as well, drafting Carlos Correa in the 2012 draft (debuting him in 2015) and drafting Alex Bregman in the 2015 draft (debuting him in the 2017 season). After another few unsuccessful seasons with records of 55-107, 51-111, and 70-92 in the 2012-2014 seasons, Jeff Luhnow decided to fire the current manager of the team, whom he had a Venkataraman and Bozzella 2 falling out with towards the end of the 2014 season. -

Major League Soccer/Triple-A Baseball Task Force Report and Recommendations Background: Summary of Initial Proposal

Major League Soccer/Triple-A Baseball Task Force Report and Recommendations March 2009 Background: For the past couple years, Major League Soccer (MLS) has been in an expansion mode. MLS returned to San Jose in 2008. Seattle was awarded the 15th team franchise in early 2008 and will begin play this year. Also in 2008, MLS awarded the 16 th franchise to Chester, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. The Chester team will start play in 2010. In the spring of 2008, MLS announced that it intended to take proposals for two additional expansion franchises which would begin play in 2011. Merritt Paulson, the owner of the Portland Timbers and Portland Beavers, approached the City and indicated he wanted to submit a proposal to MLS for one of the available expansion franchises. The franchise fee paid to MLS for an expansion team has increased dramatically during the recent expansion period. The Toronto team began play in 2007 and paid a fee of $10 million. The next year, the San Jose team began play and paid a fee of $20 million. In 2008, Seattle and Chester paid $30 million for their expansion teams. The announced fee for the two franchises to be awarded in 2009 is $40 million. Shortstop LLC is the name of the business entity formed by Mr. Paulson for the operation of the teams. The current Portland Timbers are a First Division team in the United Soccer League. This league shares an affiliation with Major League Soccer (MLS) and with the international soccer governing body FIFA. MLS is the highest level of competitive soccer played in the United States. -

White Sox Game Notes

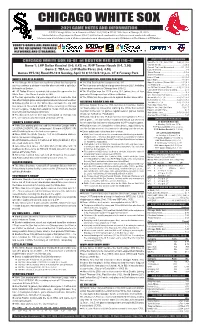

CHICAGO WHITE SOX 2021 GAME NOTES AND INFORMATION © 2021 Chicago White Sox Guaranteed Rate Field (1991) 333 W. 35th Street Chicago, Ill. 60616 Media Relations Department Phone: 312-674-5300 Email: [email protected] credentials.mlb.com whitesox.com loswhitesox.com whitesoxpressbox.com chisoxpressbox.com @whitesox @loswhitesox #WhiteSox TODAY'S GAMES ARE AVAILABLE ON THE FOLLOWING TV/RADIO NETWORKS AND STREAMING: WHITE SOX 2021 BREAKDOWN CHICAGO WHITE SOX (6-8) at BOSTON RED SOX (10-4) Sox after 14 | 15 | 16 in 2020 .......8-6 | 8-7 | 8-8 Current Streak ......................................... Lost 2 Game 1: LHP Dallas Keuchel (0-0, 6.43) vs. RHP Tanner Houck (0-1, 3.00) Current Trip | Last Homestand .............0-1 | 3-3 Game 2: TBA vs. LHP Martin Pérez (0-0, 4.50) Last 10 Games .............................................4-6 Series Record ............................................1-1-2 Games #15-16 | Road #9-10 Sunday, April 18 12:10/4:10 p.m. CT Fenway Park Series First Game.........................................3-2 Home | Road ........................................3-3 | 3-5 WHITE SOX AT A GLANCE WHITE SOX VS. BOSTON RED SOX Day | Night ............................................1-4 | 5-4 The Chicago White Sox have lost three of their last four games The Red Sox lead the season series, 1-0. Opp. At or Above | Below .500 ..............6-7 | 0-1 as they continue a six-game trip this afternoon with a split dou- The teams are scheduled to play seven times in 2021, including vs. RHS | LHS ......................................3-7 | 3-1 bleheader at Boston. a three-game series in Chicago from 9/10-12. -

A New Baseball Series from CAL RIPKEN, JR.!

A new baseball series from CAL RIPKEN, JR.! with Kevin Cowherd Greetings, fans! As any true baseball fan knows, there are a lot of important elements to being on a team. From mastering the skills of batting and catching to understanding the game, it’s a challenging sport, but one that’s rewarding and a lot of fun. The most important part of being on a successful team is being a team player and working well with others to be the best you can be. In All-Stars, the first book in my new baseball series, Connor Sullivan learns that being part of a team means learning to control your temper, even in the worst of times. In this baseball event kit, you’ll find party ideas and activities that are fun and show the importance of being part of a good team. So grab your best baseball gear, get into the team spirit, and let’s play ball! Sincerely, 3 Table of Contents Get Ready for Opening Day!.................................Page 4 Team Meeting.............................................................Page 5 Tickets for the Big Day..........................................Page 6 You’re Out!.....................................................................Page 7 Spring Training.........................................................Page 8 Practice Session........................................................Page 9 Fact or Fiction?...........................................................Page 10 Grand Slam Crossword Puzzle..........................Page 11 Design Your Own Pennant....................................Page 12 My Rookie Card..........................................................Page -

Round Rock Express 2019 GAME NOTES 3400 E

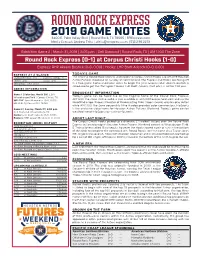

round rock Express 2019 GAME NOTES 3400 E. Palm Valley Blvd. | Round Rock, TX 78665 | RRExpress.com Media Contact: Andrew Felts | [email protected] | 512.238.2213 Exhibition Game 2 | March 31, 2019 | 2:05 p.m. | Dell Diamond | Round Rock, TX | AM 1300 The Zone Round Rock Express (0-1) at Corpus Christi Hooks (1-0) Express: RHP Akeem Bostick (0-0, 0.00) | Hooks: LHP Brett Adcock (0-0, 0.00) EXPRESS AT A GLANCE TODAY’S GAME Overall Record: 0-0 Current Streak: -- The Triple-A Round Rock Express and Double-A Corpus Christi Hooks cap off 2019 Houston Home: 0-0 Away: 0-0 Astros Futures Weekend on Sunday at Dell Diamond. The Express and Hooks are facing off Standings: T-1st (0.0) in a two-game, home-and-home series to begin the year. Express RHP Akeem Bostick is scheduled to get the start against Hooks LHP Brett Adcock. First pitch is set for 2:05 p.m. SERIES INFORMATION BROADCAST INFORMATION Game 1 | Saturday, March 30 | L 2-1 Today’s game can be heard live on the flagship home of the Round Rock Express, Whataburger Field | Corpus Christi, TX AM 1300 The Zone. Online audio is also available at am1300thezone.iheart.com and via the WP: RHP Jose Hernandez (0-0, 0.00) LP: RHP Cy Sneed (0-1, 18.00) iHeartRadio app. Express Director of Broadcasting Mike Capps handles play-by-play duties while AM 1300 The Zone personality Mike Hardge provides color commentary. FloSports Game 2 | Sunday, March 31 | 2:05 p.m.