Trends in Baldwin Criticism, 2016–17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

Dystopian America in Revolutionary Road and 'Sonny's Blues'

Dystopian America in Revolutionary Road and ‘Sonny’s Blues’ Kate Garrow America as a nation is often associated with values of freedom, nationalism, and the optimistic pursuit of dreams. However, in Revolutionary Road1 by Richard Yates and ‘Sonny’s Blues’2 by James Baldwin, the authors display a pessimistic view of America as a land characterised by suffering and entrapment, supporting the view of literary critic Leslie Fiedler that American literature is one ‘of darkness and the grotesque’.3 Through the contrasting communities of white middle-class suburbia and Harlem, the authors depict a dystopian America, where characters are stripped of their agency and forced to rely on illusions, false appearances, or escape in order to survive. Both ‘Sonny’s Blues’ and Revolutionary Road confirm that despite America’s appearance as ‘a land of light and affirmation’,4 it hides a much darker reality. Both Yates and Baldwin use characteristics of dystopian literature to create their respective American societies. Revolutionary Road is set in a white middle-class suburban society fuelled by materialism and false appearances. In particular, the community demands conformity. Men must succumb to a bland office job that ‘would swallow them up’5 and 1 R. Yates, Revolutionary Road, London, Random House, 2007. 2 A. Baldwin, ‘Sonny’s Blues’, in Going to Meet the Man, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013. 3 L. Fiedler, Love and Death in the American Novel, Stein and Day, 1960, p. 29. 4 Fiedler, p. 29. 5 Yates, Revolutionary Road, p. 119. Burgmann Journal VI (2017) women must accept the feminine role as submissive housewife. -

Going to Meet the Man”: Scripting White Supremacist Eros

Benlloch ENG 390: Final “Going to Meet the Man”: Scripting White Supremacist Eros In order to be utilized, our erotic feelings must be recognized. The need for sharing deep feeling is a human need. But within the european-american tradition, this need is satisfied by certain proscribed erotic comings-together. These occasions are almost always characterized by a simultaneous looking away, a pretense of calling them something else, whether a religion, a fit, mob violence, or even playing doctor. –Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” (emphasis mine) If we think of “flesh” as a primary narrative, then we mean its seared, divided, ripped-apartness, riveted to the ship’s hole, fallen, or escaped overboard. —Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe” All attempts to explain the malicious standard operating procedure of the US white supremacy find themselves hamstrung by conceptual inadequacy; it remains describable, but not comprehensible. —Steve Martinot and Jared Sexton, “The Avant-Garde of White Supremacy” Introduction In 1931, Raymond Gunn was burned to death, his still living body dragged to the top of a Maryville, Missouri schoolhouse, bound to the ridgepole by a horde of unmasked local men, and doused in gasoline (Kremer 359). Before the schoolhouse collapsed in a billowing inferno, leaving Raymond’s body to disintegrate in a manner of minutes, spectators confirmed the presence of the mob leader, an outsider in a red coat who led the lynch mob and who was ultimately responsible for throwing a flaming piece of paper into the gasoline-soaked building (Kremer 360). Despite the outsider’s eponymous red coat, the identity of the mob leader remains anonymous to history, yet I argue that “the man in the red coat,” far from being ‘unknown,’ is an all too overt and present amalgam for the civil roots of the eroticization of the color line in the United States. -

Beauford Delaney & James Baldwin

BEAUFORD DELANEY & JAMES BALDWIN: THROUGH THE UNUSUAL DOOR selected timeline Beauford Delaney 1940 Meets Delaney for the first time 1961 While traveling by boat across 1970 Buys a home at Saint-Paul-de- James Baldwin at the artist’s 181 Greene Street studio. the Mediterranean to Greece, jumps Vence, in the South of France. 1941 Spends Christmas with his fam- overboard in a suicide attempt and is 1971 Travels to London to appear with 1901 Born Knoxville, Tennessee, ily in Knoxville. Appears in Delaney’s rescued by a fisherman. Friends pay poet/activist Nikki Giovanni on the on December 30 to Delia Johnson art for the first time in Dark Rapture for his return to Paris and hospitaliza- television program Soul. At his new Delaney and the Reverend John Samuel (James Baldwin). tion. Second essay collection, Nobody home, he is visited frequently by an Delaney, 815 East Vine Avenue. Knows My Name, published by Dial. 1942 Graduates from DeWitt Clinton increasingly unstable Delaney, who 1919 Father dies on April 30. Rioting Makes first trip to Istanbul, where he High School. sees Baldwin’s home as a refuge. breaks out in August after an African finishes writing his third novel, Another 1972 Publishes No Name in the Street, American man, Maurice Franklin Mays, 1943 Stepfather David Baldwin dies. Country. his fourth book of non-fiction, and is accused of murdering a white woman 1944 Appears in Delaney’s pastel 1962 Moves to 53 Rue Vercingetorix dedicates it to Delaney. in what would later become known as Portrait of James Baldwin. in Montparnasse. -

Sonny's Blues Study Guide

Sonny's Blues Study Guide © 2018 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary The narrator, a teacher in Harlem, has escaped the ghetto, creating a stable and secure life for himself despite the destructive pressures that he sees destroying so many young blacks. He sees African American adolescents discovering the limits placed on them by a racist society at the very moment when they are discovering their abilities. He tells the story of his relationship with his younger brother, Sonny. That relationship has moved through phases of separation and return. After their parents’ deaths, he tried and failed to be a father to Sonny. For a while, he believed that Sonny had succumbed to the destructive influences of Harlem life. Finally, however, they achieved a reconciliation in which the narrator came to understand the value and the importance of Sonny’s need to be a jazz pianist. The story opens with a crisis in their relationship. The narrator reads in the newspaper that Sonny was taken into custody in a drug raid. He learns that Sonny is addicted to heroin and that he will be sent to a treatment facility to be “cured.” Unable to believe that his gentle and quiet brother could have so abused himself, the narrator cannot reopen communication with Sonny until a second crisis occurs, the death of his daughter from polio. -

“Going to Meet the Man” and Police Brutality in the United States

XULAneXUS Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 1 12-20-2019 James Baldwin’s “Going to Meet the Man” and Police Brutality in The United States Sinai Akpan Xavier University of Louisiana, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.xula.edu/xulanexus Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Recommended Citation Akpan, Sinai (2019) "James Baldwin’s “Going to Meet the Man” and Police Brutality in The United States," XULAneXUS: Vol. 17 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.xula.edu/xulanexus/vol17/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by XULA Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in XULAneXUS by an authorized editor of XULA Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Akpan: Police Brutality James Baldwin’s “Going to Meet the Man” and Police Brutality in The United States The black aesthetic was birthed by artists during the Black Arts movement. The black aesthetic was a psychological breakaway from the dismissive Western ideologies that represented African Americans as an opposition. At the heart of the Black Arts movement was black love. Self-love and love for the community was essential. There was also an emphasis on African American artists’ ability to interpret their individual value. These artists were encouraged to find their worth and importance within themselves. During this time many artists believed black art should be both political and express the African American lived experience. This was a time for racial political radicalism and retaliation. Many artists used their platform to speak out against police brutality, demand voting rights for African Americans, and champion the upward mobility of African Americans. -

“Here Be Dragons:” the Tyranny of the Cityscape in James Baldwin's Intimate Cartographies

ESSAY “Here Be Dragons:” The Tyranny of the Cityscape in James Baldwin’s Intimate Cartographies Emma Cleary Staffordshire University Abstract The skyline of New York projects a dominant presence in the works of James Baldwin—even those set elsewhere. This essay analyzes the socio-spatial rela- tionships and cognitive maps delineated in Baldwin’s writing, and suggests that some of the most compelling and intense portrayals of New York’s psychogeo- graphic landscape vibrate Baldwin’stext.InThe Price of the Ticket (1985), Baldwin’s highly personalized accounts of growing up in Harlem and living in New York map the socio-spatial relationships at play in domestic, street, and blended urban spaces, particularly in the title essay, “Dark Days,” and “Here Be Dragons.” Baldwin’sthirdnovel,Another Country (1962), outlines a multi- striated vision of New York City; its occupants traverse the cold urban territory and struggle beneath the jagged silhouette of skyscrapers. This essay examines the ways in which Baldwin composes the urban scene in these works through complex image schemas and intricate geometries, the city’s levels, planes, and perspectives directing the movements of its citizens. Further, I argue that Baldwin’s dynamic use of visual rhythms, light, and sound in his depiction of black life in the city, creates a vivid cartography of New York’s psychogeographic terrain. This essay connects Baldwin’s mappings of Harlem to an imbricated visual and sonic conception of urban subjectivity, that is, how the subject is con- structed through a simultaneous and synaesthetic visual/scopic and aural/sonic relation to the city, with a focus on the movement of the body through city space. -

Sonny's Blues

BALDWIN I Sonny's Blues JAMES BALDWIN [1924-1987] going to choke or scream. This would always be at a moment when I was remembering some specific thing Sonny had once said or done. When he was about as old as the boys in my classes his face had been Sonny's Blues bright and open, there was a lot of copper in it; and he'd had wonderfully direct brown eyes, and great gentleness and privacy. I wondered what he looked like now. He had been picked up, the evening before,_in a raid on an apartment downtown, for peddling and using heroin. ' I couldn't believe it: but what I mean by that is that I couldn't find any Born in New York City, the son of a revivalist minister, James Baldwin (1924-1987) was raised in poverty in Harlem where, at the age of fo1.1r room for it anywhere inside me. I had kept it outside me for a long time. teen, he became a preacher in the Fireside Pentecostal Church. After I hadn't wanted to know. I had had suspicions, but I didn't name them, I completing high school he decided to become a writer and, with the kept putting them away. I told myself that Sonny was wild, but he wasn't help of the black American expatriate writer Richard Wright, won a crazy. And he'd always been a good boy, he hadn't ever tur1,1ed hard or grant that enabled him to move to Paris, where he lived for most of his evil or disrespectful, the way kids can, so quick, so quick, especially in remaining years, There he wrote the critically acclaimed Go Tell It on the Harlem. -

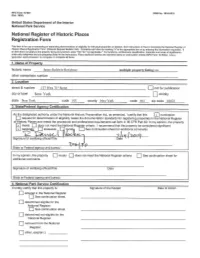

James Baldwin Residence Multiple Property Listing: No Other Names/Site Number 2

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name James Baldwin Residence multiple property listing: no other names/site number 2. Location street & number 137 West 71st Street not for publication city or town New York vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10023 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this x nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant x nationally statewide locally. -

Circulating Emotions in James Baldwin's Going to Meet the Man

Circulating Emotions in James Baldwin’s Going to Meet the Man and in American Society Av: Alexandra Cassel Handledare: Kerstin Shands Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för Kultur & Lärande Kandidatuppsats 30 hp Engelska | Höstterminen 2016 Table of Content Abstract ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1Aim ................................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Going to Meet the Man ................................................................................................................. 2 2.0 Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................................................... 3 3.0 Previous Research .............................................................................................................................. 8 4.0 Analysis .............................................................................................................................................. 10 4.1 The Uncanny ............................................................................................................................... 10 4.2 Shivering and Fear ..................................................................................................................... -

Oppression Through Sexualization: the Seu of Sexualization in “Going to Meet the Man” and “The Shoyu Kid” Joe Gorman

Undergraduate Review Volume 5 Article 24 2009 Oppression through Sexualization: The seU of Sexualization in “Going to Meet the Man” and “The Shoyu Kid” Joe Gorman Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gorman, Joe (2009). Oppression through Sexualization: The sU e of Sexualization in “Going to Meet the Man” and “The hoS yu Kid”. Undergraduate Review, 5, 119-124. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol5/iss1/24 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2009 Joe Gorman Oppression through Sexualization: The Use of Sexualization in “Going to Meet the Man” and “The Shoyu Kid” JOE GORMAN Joe is a senior majoring in English White supremacy is a fleshy ideology; it’s very much about bodies. -- Mason Stokes with a minor in Secondary Education. After his time at Bridgewater State n a world of differences and misunderstandings, disparities and distance, College, he plans to attend graduate there is a seemingly endless myriad of modes by which human beings school and a career as an educator. categorize, segregate, and immobilize each other. History is filled with repeated instances of groups asserting themselves through any necessary means Joe wrote the following piece under Iin order to retain dominance and power. In a rather unnerving way, the human the mentorship of Dr. Kimberly race can prove to be quite creative in its tenacity to oppress. Obviously, racism and Chabot- Davis in the senior seminar cultural repression have proven to be weapons of choice time and again. -

The Cage of Reality: Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin's Fiction

The Cage of Reality Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin’s Fiction Regine Lundevall Bergersen A Thesis Presented to the Department of Literature, Area Studies, and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s of Arts Degree SPRING 2017 I II The Cage of Reality Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin’s Fiction Regine Lundevall Bergersen III Copyright Regine Lundevall Bergersen 2017 The Cage of Reality: Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin’s Fiction Regine Lundevall Bergersen http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract This thesis explores issues and processes of identity in three pieces of James Baldwin’s fiction: “Going to Meet the Man” (1965), Giovanni’s Room (1956), and Another Country (1962). The point of departure is Baldwin’s concept of “the cage of reality,” a term used to describe the ways in which society traps the individual in a mold of assigned identity, and from which one cannot escape, but can hope to be free from through acknowledgement. The processes of acknowledging or ignoring the cage of reality is what this thesis explores in central characters in these three works, and this study finds that American society is riddled with a trait Baldwin calls “preservation of innocence,” translatable to a willful ignorance of the cage of reality, which explains the persistence of harmful identity norms. The key to overcoming the cage of reality is, according to Baldwin, to take responsibility, and accept that all individuals exist in a “web of ambiguity.” This thesis uses critical race theory and some psychoanalytical approaches to the short story “Going to Meet the Man,” and a selection of existentialist terms in the readings of Giovanni’s Room and Another Country.