AG-636-02 Butterflies in Your Backyard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panicledleaf Ticktrefoil (Desmodium Paniculatum) Plant Fact Sheet

Plant Fact Sheet Hairstreak (Strymon melinus) eat the flowers and PANICLEDLEAF developing seedpods. Other insect feeders include many kinds of beetles, and some species of thrips, aphids, moth TICKTREFOIL caterpillars, and stinkbugs. The seeds are eaten by some upland gamebirds (Bobwhite Quail, Wild Turkey) and Desmodium paniculatum (L.) DC. small rodents (White-Footed Mouse, Deer Mouse), while Plant Symbol = DEPA6 the foliage is readily eaten by White-Tailed Deer and other hoofed mammalian herbivores. The Cottontail Contributed by: USDA, NRCS, Norman A. Berg National Rabbit also consumes the foliage. Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, MD Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description and Adaptation Panicledleaf Ticktrefoil is a native, perennial, wildflower that grows up to 3 feet tall. The genus Desmodium: originates from Greek meaning "long branch or chain," probably from the shape and attachment of the seedpods. The central stem is green with clover-like, oblong, multiple green leaflets proceeding singly up the stem. The showy purple flowers appear in late summer and grow arranged on a stem maturing from the bottom upwards. In early fall, the flowers produce leguminous seed pods approximately ⅛ inch long. Panicledleaf Photo by Rick Mark [email protected] image used with permission Ticktrefoil plants have a single crown. This wildflower is a pioneer species that prefers some disturbance from Alternate Names wildfires, selective logging, and others causes. The sticky Panicled Tick Trefoil seedpods cling to the fur of animals and the clothing of Uses humans and are carried to new locations. -

Butterflies of the Wesleyan Campus

BUTTERFLIES OF THE WESLEYAN CAMPUS SWALLOWTAILS Hairstreaks (Subfamily - Theclinae) (Family PAPILIONIDAE) Great Purple Hairstreak - Atlides halesus Coral Hairstreak - Satyrium titus True Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak - Satyrium calanus (Subfamily - Papilioninae) Striped Hairstreak - Satyrium liparops Pipevine Swallowtail - Battus philenor Henry’s Elfin - Callophrys henrici Zebra Swallowtail - Eurytides marcellus Eastern Pine Elfin - Callophrys niphon Black Swallowtail - Papilio polyxenes Juniper Hairstreak - Callophrys gryneus Giant Swallowtail - Papilio cresphontes White M Hairstreak - Parrhasius m-album Eastern Tiger Swallowtail - Papilio glaucus Gray Hairstreak - Strymon melinus Spicebush Swallowtail - Papilio troilus Red-banded Hairstreak - Calycopis cecrops Palamedes Swallowtail - Papilio palamedes Blues (Subfamily - Polommatinae) Ceraunus Blue - Hemiargus ceraunus Eastern-Tailed Blue - Everes comyntas WHITES AND SULPHURS Spring Azure - Celastrina ladon (Family PIERIDAE) Whites (Subfamily - Pierinae) BRUSHFOOTS Cabbage White - Pieris rapae (Family NYMPHALIDAE) Falcate Orangetip - Anthocharis midea Snouts (Subfamily - Libytheinae) American Snout - Libytheana carinenta Sulphurs and Yellows (Subfamily - Coliadinae) Clouded Sulphur - Colias philodice Heliconians and Fritillaries Orange Sulphur - Colias eurytheme (Subfamily - Heliconiinae) Southern Dogface - Colias cesonia Gulf Fritillary - Agraulis vanillae Cloudless Sulphur - Phoebis sennae Zebra Heliconian - Heliconius charithonia Barred Yellow - Eurema daira Variegated Fritillary -

Register Now for Williamsburg Gathering

i Sempervirens Summer 2018 The Quarterly of the Virginia Native Plant Society 2018 Annual Meeting Set for Sept. 14–16 Register now for Williamsburg gathering Article by Cortney Will, John Clayton Chapter e the members of the The conference opens Friday W John Clayton Chapter are evening with an interactive excited to be hosting this year’s presentation by the nonprofit Virginia annual meeting, “Sustaining Center for Inclusive Communities Nature, Sustaining Ourselves,” (VCIC). The center’s work has its over the weekend of Sept. 14–16 roots in the 1930s, when it was at the William & Mary School of organized as a grassroots movement Jessica Hawthorne Kevin Bryan Education in Williamsburg. responding to religious intolerance. environmental justice, and grassroots We have arranged roughly a It has evolved and expanded in the conservation organizations that dozen options for field trips and intervening 80 years, and today the pursue a shared vision of a more plant walks, in addition to excellent center provides programming that diverse and inclusive culture in food and innovative speakers. Walks helps Virginia’s schools, businesses, managing and preserving the will offer a diversity of habitats and communities achieve success nation’s public lands. and local features, including tidal through inclusion. We will welcome While the conference formally salt marshes, hardwood forests, Jessica Hawthorne, director of begins on Friday night, we’re hoping cypress swamps, vernal pools, and programs, who designs and facilitates you’ll join us beforehand for dinner at the William & Mary herbarium, VCIC’s assemblies, one-day youth the Corner Pocket before the program. greenhouse, and College Woods. -

Superior National Forest

Admirals & Relatives Subfamily Limenitidinae Skippers Family Hesperiidae £ Viceroy Limenitis archippus Spread-wing Skippers Subfamily Pyrginae £ Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus clarus £ Dreamy Duskywing Erynnis icelus £ Juvenal’s Duskywing Erynnis juvenalis £ Northern Cloudywing Thorybes pylades Butterflies of the £ White Admiral Limenitis arthemis arthemis Superior Satyrs Subfamily Satyrinae National Forest £ Common Wood-nymph Cercyonis pegala £ Common Ringlet Coenonympha tullia £ Northern Pearly-eye Enodia anthedon Skipperlings Subfamily Heteropterinae £ Arctic Skipper Carterocephalus palaemon £ Mancinus Alpine Erebia disa mancinus R9SS £ Red-disked Alpine Erebia discoidalis R9SS £ Little Wood-satyr Megisto cymela Grass-Skippers Subfamily Hesperiinae £ Pepper & Salt Skipper Amblyscirtes hegon £ Macoun’s Arctic Oeneis macounii £ Common Roadside-Skipper Amblyscirtes vialis £ Jutta Arctic Oeneis jutta (R9SS) £ Least Skipper Ancyloxypha numitor Northern Crescent £ Eyed Brown Satyrodes eurydice £ Dun Skipper Euphyes vestris Phyciodes selenis £ Common Branded Skipper Hesperia comma £ Indian Skipper Hesperia sassacus Monarchs Subfamily Danainae £ Hobomok Skipper Poanes hobomok £ Monarch Danaus plexippus £ Long Dash Polites mystic £ Peck’s Skipper Polites peckius £ Tawny-edged Skipper Polites themistocles £ European Skipper Thymelicus lineola LINKS: http://www.naba.org/ The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination http://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/ in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national -

Butterflies of Kootenai County 958 South Lochsa St Post Falls, ID 83854

Butterflies of Kootenai County 958 South Lochsa St Post Falls, ID 83854 Phone: (208) 292-2525 Adapted from Oregon State University Extension FAX: (208) 292-2670 Booklet EC 1549 and compiled by Mary V., Certified E-mail: [email protected] Idaho Master Gardener. Web: uidaho.edu/kootenai By growing a bounty of native plants, mixed with nearly-natives or non-natives, you can attract a variety of butterflies. Additional reading: https://xerces.org/your-pollinator-garden/ Butterflies favor platform-shaped flowers but will feed on a diversity of nectar-rich http://millionpollinatorgardens.org/ flowers. They prefer purple, red, orange, https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinator violet, and yellow flower colors with sweet s/documents/AttractingPollinatorsV5.pdf scents. Butterflies love warm, sunny and http://xerces.org/pollinators-mountain- windless weather. region/ Planning your garden – Think like a o Tolerate Damage on your Plants: A butterfly Pollinator garden needs plants that feed larvae o Go Native: Pollinators are best adapted to (caterpillars). They feed on leaves and plant local, native plants which often need less material. If you do not feed the young, the water than ornamentals. adults will not stay in your landscapes. o Plant in Groups of three or more: Planting o Provide a puddle as a water source: Allow large patches of each plant species for better water to puddle in a rock or provide a foraging efficiency. shallow dish filled with sand as a water source for butterflies. Float corks or a stick o Blooming All Season: Flowers should bloom in your garden throughout the in the puddles to allow insects that fall in to growing season. -

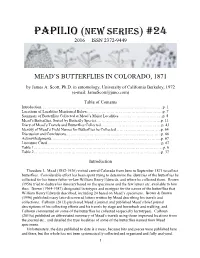

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

Butterfly Station & Garden

Butterfly Station & Garden Tour the Butterfly Station & Garden to view some of nature’s most beautiful creatures! Discover a variety of native and non-native butterflies. Find out which type of caterpillar eats certain plants, learn the best methods to attract butterflies and get inspired to create Butterfly your own butterfly garden. Available mid-April through mid-September. Station & Garden Host your next BUTTERFLY IDENTIFICATION GUIDE event at the Butterfly Station & Garden. Call 434.791.5160, ext 203. for details. Supporting the Butterfly Station & Garden Thanks to generous support from the community the Butterfly Station & Garden has been free to the public since opening in 1999. If you would like to support the Butterfly Station & Garden, please call 434.791.5160, ext. 203. Tax deductible gifts may be made to Danville Science Center, Inc., designated for the Butterfly Station. Connect We are grateful to the many volunteers who make the with us! Science Center’s Butterfly Station & Garden a reality. 677 Craghead Street Call us to set up a time to volunteer, if you would Danville, Virginia like to help manage the gardens. 434.791.5160 | dsc.smv.org Native Butterflies Non-Native Butterflies Black Swallowtail Monarch Great Southern White (Papilio Polyxenes) (Danaus Plexippus) (Ascia Monuste) Named after woman in Greek One variation, the “white These butterflies are often mythology, Polyxena, who was monarch”, is grayish-white in used in place of doves at the youngest daughter of King all areas of its wings that are wedding ceremonies. Priam of Troy. normally orange. FOUND IN SOUTH ATLANTIC Julia Longwing Cloudless Sulphur Mourning Cloak (Dryas Iulia) (Phoebis Sennae) (Nymphalis Antiopa) Julias can see yellow, green, Its genus name is derived from These butterflies hibernate and red. -

Butterflies and Moths List

Lepidoptera of Kirchoff Family Farm Baseline Survey October 29-30, 2012 Butterflies & Moths Host Plant Species Present Date Butterflies Observed On Larval Host Plants Kirchoff FF observed Family Papilionidae (Swallowtails) Pipevine Swallowtail - Battus philenor Spiny Aster Pipevine √ Oct. 30, 2012 Family Pieridae (Whites & Sulfurs) Cloudless Sulfur - Phoebis sennae Spiny Aster Legumes, clovers, peas √ Oct. 29, 2012 Dainty Sulfur - Nathalis iole Spiny Aster Asters, other Com;posites √ Oct. 29, 2012 Little Yellow Sulfur - Eurema lisa Indian Mallow Legumes, partridge pea √ Oct. 29, 2012 Lyside Sulfur - Kirgonia lyside Spiny Aster Guayacan or Soapbush √ Oct. 29, 2012 Orange Sulfur - Colias eurytheme Spiny Aster Legumes √ Sept. 26, 2007 Family Lycaenidae (Gossamer Winged) Cassius Blue - Leptotes cassius Spiny Aster Legumes √ Oct. 30, 2012 Ceraunus Blue - Hemiargus ceraunus Kidney wood Legumes- Acacia, Mesquite √ Oct. 30, 2012 Fatal Metalmark - Calephelis nemesis Spiny Aster Baccharis, Clematis √ Oct. 29, 2012 Gray Hairstreak - Strymon melinus Frostweed, Aster Many flowering plants √ Oct. 29, 2012 Great Purple Hairstreak - Atlides halesus Spiny Aster Mistletoe (in oak/mesquite) √ Oct. 29, 2012 Marine Blue - Leptotes marina Frogfruit Legumes- Acacia, Mesquite √ Oct. 30, 2012 Family Nymphalidae (Nymphalids) American Snout - Libytheana carinenta Spiny Aster Hackberries √ Oct. 29, 2012 Bordered Patch - Chlosyne lacinia Zexmenia Ragweed, Sunflower √ Oct. 29, 2012 Common Mestra - Mestra amymone Frostweed Noseburn (Tragia spp.) X Oct. 29, 2012 Empress Leila - Asterocampa leilia Spiny Aster Spiny Hackberry √ Oct. 29, 2012 Gulf Fritillary - Agraulis vanillae Spiny Aster Passion Vine X Oct. 29, 2012 Hackberry Emperor - Asterocampa celtis spiny Hackberry Hackberries √ Oct. 29, 2012 Painted Lady - Vanessa cardui Pink Smartweed Mallows & Thistles √ Oct. 29, 2012 Pearl Crescent - Phycoides tharos Spiny Aster Asters √ Oct. -

Redalyc.Nymphalis Antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Maltese

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Seguna, A. Nymphalis antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Maltese Islands (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 41, núm. 164, octubre-diciembre, 2013, pp. 569-570 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45530406014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 569-570 Nymphalis antiopa (Linn 2/12/13 16:57 Página 569 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 41 (164), diciembre 2013: 569-570 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 Nymphalis antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Maltese Islands (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) A. Seguna Abstract An account is given of this first record of Nymphalis antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) from the Maltese Islands. KEY WORDS: Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Nymphalis antiopa, new record, Malta Islands. Nymphalis antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) en Malta (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Resumen Se indica a Nymphalis antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) por primera vez para Malta. PALABRAS CLAVE: Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Nymphalis antiopa, nueva cita, Malta. Introduction The Nymphalidae is a large family well represented in Europe. A few of them are strong migrants, capable of extending their range during the summer months. The discovery of Nymphalis antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) in Malta is most interesting as it a species associated more with colder climates, and its presence in Malta is best regarded as an accidental human important, more so because the place where it was collected is very near the Free Port [where container ships load and unload containers coming from all parts of the world], Bir¿ebbugia. -

Butterflies of Tennessee Alphabetical by Common Name Butterflies Of

1 Butterflies of Tennessee Butterflies of Tennessee Alphabetical by Common Name Page 2 Butterflies of Tennessee Alphabetical by Scientific Name Page 6 Butterflies of Tennessee Alphabetical by Family Page 10 The Middle Tennessee Chapter of the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) maintains the list of Butterflies in Tennessee. Check their website at: nabamidtn.org/?page_id=176 Updated March 2015 1 2 Butterflies of Tennessee Alphabetical by Common Name Common Name Scientific Name Family American Copper Lycaena phlaeas Lycaenidae American Lady Vanessa virginiensis Nymphalidae American Snout Libytheana carinenta Nymphalidae Aphrodite Fritillary Speyeria aphrodite Nymphalidae Appalachian Azure Celestrina neglectamajor Lycaenidae Appalachian Brown Satyrodes appalachia Nymphalidae Appalachian Tiger Swallowtail Papilio appalachiensis Papilionidae Baltimore Checkerspot Euphydryas phaeton Nymphalidae Banded Hairstreak Satyrium calanus Lycaenidae Bell’s Roadside-Skipper Amblyscirtes belli Hesperiidae Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes Papilionidae Brazilian Skipper Calpodes ethlius Hesperiidae Broad-winged Skipper Poanes viator Hesperiidae Bronze Copper Lycaena hyllus Lycaenidae Brown Elfin Callophrys augustinus Lycaenidae Cabbage White Pieris rapae Pieridae Carolina Satyr Hermeuptychia sosybius Nymphalidae Checkered White Pontia protodice Pieridae Clouded Skipper Lerema accius Hesperiidae Clouded Sulphur Colias philodice Pieridae Cloudless Sulphur Phoebis sennae Pieridae Cobweb Skipper Hesperia metea Hesperiidae Common Buckeye Junonia coenia -

How to Use This Checklist

How To Use This Checklist Swallowtails: Family Papilionidae Special Note: Spring and Summer Azures have recently The information presented in this checklist reflects our __ Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor R; May - Sep. been recognized as separate species. Azure taxonomy has not current understanding of the butterflies found within __ Zebra Swallowtail Eurytides marcellus R; May - Aug. been completely sorted out by the experts. Cleveland Metroparks. (This list includes all species that have __ Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes C; May - Sep. __ Appalachian Azure Celastrina neglecta-major h; mid - late been recorded in Cuyahoga County, and a few additional __ Giant Swallowtail Papilio cresphontes h; rare in Cleveland May; not recorded in Cuy. Co. species that may occur here.) Record you observations and area; July - Aug. Brush-footed Butterflies: Family Nymphalidae contact a naturalist if you find something that may be of __ Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Papilio glaucus C; May - Oct.; __ American Snout Libytheana carinenta R; June - Oct. interest. females occur as yellow or dark morphs __ Variegated Fritillary Euptoieta claudia R; June - Oct. __ Spicebush Swallowtail Papilio troilus C; May - Oct. __ Great Spangled Fritillary Speyeria cybele C; May - Oct. Species are listed taxonomically, with a common name, a Whites and Sulphurs: Family Pieridae __ Aphrodite Fritillary Speyeria aphrodite O; June - Sep. scientific name, a note about its relative abundance and flight __ Checkered White Pontia protodice h; rare in Cleveland area; __ Regal Fritillary Speyeria idalia X; no recent Ohio records; period. Check off species that you identify within Cleveland May - Oct. formerly in Cleveland Metroparks Metroparks. __ West Virginia White Pieris virginiensis O; late Apr. -

Specimen Records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895

Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection 2019 Vol 3(2) Specimen records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895 Jon H. Shepard Paul C. Hammond Christopher J. Marshall Oregon State Arthropod Collection, Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis OR 97331 Cite this work, including the attached dataset, as: Shepard, J. S, P. C. Hammond, C. J. Marshall. 2019. Specimen records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895. Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection 3(2). (beta version). http://dx.doi.org/10.5399/osu/cat_osac.3.2.4594 Introduction These records were generated using funds from the LepNet project (Seltmann) - a national effort to create digital records for North American Lepidoptera. The dataset published herein contains the label data for all North American specimens of Lycaenidae and Riodinidae residing at the Oregon State Arthropod Collection as of March 2019. A beta version of these data records will be made available on the OSAC server (http://osac.oregonstate.edu/IPT) at the time of this publication. The beta version will be replaced in the near future with an official release (version 1.0), which will be archived as a supplemental file to this paper. Methods Basic digitization protocols and metadata standards can be found in (Shepard et al. 2018). Identifications were confirmed by Jon Shepard and Paul Hammond prior to digitization. Nomenclature follows that of (Pelham 2008). Results The holdings in these two families are extensive. Combined, they make up 25,743 specimens (24,598 Lycanidae and 1145 Riodinidae).