Postman's Park Conservation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delegated Decisions of the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director

Committee: Date: Planning and Transportation 29 April 2014 Subject: Delegated decisions of the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director Public 1. Pursuant to the instructions of your Committee, I attach for your information a list detailing development and advertisement applications determined by the Chief Planning Officer or the Development Division Assistant Directors under their delegated powers since my report to the last meeting. 2. Any questions of detail arising from these reports can be sent to [email protected]. DETAILS OF DECISIONS Registered Plan Address Proposal Date of Number & Ward Decision 13/01229/FULL Bankside House 107 - Change of use from office (B1) 04.04.2014 112 Leadenhall Street to a drinking establishment Aldgate London (A4) at part ground floor level EC3A 4AF and part basement. Associated external works to ground floor rear entrance. (887sq.m). 13/01212/LBC 603 Mountjoy House Internal alterations comprising 03.04.2014 Barbican removal of internal partition Aldersgate London walls, formation of new EC2Y 8BP partition walls, relocation of main staircase and installation of additional staircase. 13/01205/FULL Flat 49, Milton House The erection of an extension at 27.03.2014 75 Little Britain roof level for residential (Class Aldersgate London C3) use. (28sq.m) EC1A 7BT 14/00074/FULL 53 New Broad Street Replacement of windows to 03.04.2014 London front facade; provision of new Broad Street EC2M 1JJ stepped access within lightwell to basement level; alterations at 5th floor level to provide additional mechanical plant and new louvred plant screens. 14/00122/MDC 1 Angel Court & 33 Details of a scheme for 03.04.2014 Throgmorton Street protecting nearby residents Broad Street London and commercial occupiers EC2R 7HJ from noise, dust and other environmental effects pursuant to condition 3 of planning permission 10/00889/FULMAJ dated 15/03/2013. -

Death, Time and Commerce: Innovation and Conservatism in Styles of Funerary Material Culture in 18Th-19Th Century London

Death, Time and Commerce: innovation and conservatism in styles of funerary material culture in 18th-19th century London Sarah Ann Essex Hoile UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Declaration I, Sarah Ann Essex Hoile confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis explores the development of coffin furniture, the inscribed plates and other metal objects used to decorate coffins, in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century London. It analyses this material within funerary and non-funerary contexts, and contrasts and compares its styles, production, use and contemporary significance with those of monuments and mourning jewellery. Over 1200 coffin plates were recorded for this study, dated 1740 to 1853, consisting of assemblages from the vaults of St Marylebone Church and St Bride’s Church and the lead coffin plates from Islington Green burial ground, all sites in central London. The production, trade and consumption of coffin furniture are discussed in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 investigates coffin furniture as a central component of the furnished coffin and examines its role within the performance of the funeral. Multiple aspects of the inscriptions and designs of coffin plates are analysed in Chapter 5 to establish aspects of change and continuity with this material. In Chapter 6 contemporary trends in monuments are assessed, drawing on a sample recorded in churches and a burial ground, and the production and use of this above-ground funerary material culture are considered. -

Smithfield Market but Are Now Largely Vacant

The Planning Inspectorate Report to the Temple Quay House 2 The Square Temple Quay Secretary of State Bristol BS1 6PN for Communities and GTN 1371 8000 Local Government by K D Barton BA(Hons) DipArch DipArb RIBA FCIArb an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State Date 20 May 2008 for Communities and Local Government TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS AND CONSERVATION AREAS) ACT 1990 APPLICATIONS BY THORNFIELD PROPERTIES (LONDON) LIMITED TO THE CITY OF LONDON COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT AT 43 FARRINGDON STREET, 25 SNOW HILL AND 29 SMITHFIELD STREET, LONDON EC1A Inquiry opened on 6 November 2007 File Refs: APP/K5030/V/07/1201433-36 Report APP/K5030/V/07/1201433-36 CONTENTS SECTION TITLE PAGE 1.0 Procedural Matters 3 2.0 The Site and Its Surroundings 3 3.0 Planning History 5 4.0 Planning Policy 6 5.0 The Case for the Thornfield Properties (London) 7 Limited 5.1 Introduction 7 5.2 Character and Appearance of the Surrounding Area 8 including the Settings of Nearby Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas 5.3 Viability 19 5.4 Repair, maintenance and retention of the existing buildings 23 5.5 Sustainability and Accessibility 31 5.6 Retail 31 5.7 Transportation 32 5.8 Other Matters 33 5.9 Section 106 Agreement and Conditions 35 5.10 Conclusion 36 6.0 The Case for the City of London Corporation 36 6.1 Introduction 36 6.2 Character and Appearance of the Surrounding Area 36 including the Settings of Nearby Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas 6.3 Viability 42 6.4 Repair, maintenance and retention of the existing buildings -

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London Christine Winter Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London Royal Holloway, University of London, 2012 2 Declaration I, Christine Winter, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 3 Abstract In the history of crime and punishment the prisons of medieval London have generally been overlooked. This may have been because none of the prison records have survived for this period, yet there is enough information in civic and royal documents, and through archaeological evidence, to allow a reassessment of London’s prisons in the later middle ages. This thesis begins with an analysis of the purpose of imprisonment, which was not merely custodial and was undoubtedly punitive in the medieval period. Having established that incarceration was employed for a variety of purposes the physicality of prison buildings and the conditions in which prisoners were kept are considered. This research suggests that the periodic complaints that London’s medieval prisons, particularly Newgate, were ‘foul’ with ‘noxious air’ were the result of external, rather than internal, factors. Using both civic and royal sources the management of prisons and the abuses inflicted by some keepers have been analysed. This has revealed that there were very few differences in the way civic and royal prisons were administered; however, there were distinct advantages to being either the keeper or a prisoner of the Fleet prison. Because incarceration was not the only penalty available in the enforcement of law and order, this thesis also considers the offences that constituted a misdemeanour and the various punishments employed by the authorities. -

1 Giltspur Street

1 GILTSPUR STREET LONDON EC1 1 GILTSPUR STREET 1 GILTSPUR STREET INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS • Occupies a prominent corner position in the heart of Midtown, where the City of London and West End markets converge. • Situated on the west side of Giltspur Street at its junction with West Smithfield and Hosier Lane to the north and Cock Lane to the south. • In close proximity to Smithfield Market and Farringdon Station to the north. • Excellent transport connectivity being only 200m from Farringdon Station which, upon delivery of the Elizabeth Line in autumn 2019, will be the only station in Central London to provide direct access to London Underground, the Elizabeth Line, Thameslink and National Rail services. • 23,805 sq. ft. (2,211.4 sq. m.) of refurbished Grade A office and ancillary accommodation arranged over lower ground, ground and four upper floors. • Held long leasehold from The Mayor and Commonalty of the City of London for a term of 150 years from 24 June 1991 expiring 23 June 2141 (approximately 123 years unexpired) at a head rent equating to 7.50% of rack rental value. • Vacant possession will be provided no later than 31st August 2019. Should completion of the transaction occur prior to this date the vendor will remain in occupation on terms to be agreed. We are instructed to seek offers in excess of£17 million (Seventeen Million Pounds), subject to contract and exclusive of VAT, for the long leasehold interest, reflecting a low capital value of £714 per sq. ft. 2 3 LOCATION & SITUATION 1 Giltspur Street is located in a core Central London location in the heart of Midtown where the City of London and West End markets converge. -

Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt

Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt What better way to celebrate The Senior Section Spectacular than by exploring one of the greatest cities in the world! London is full of interesting places, monuments and fascinating museums, many of which are undiscovered by visitors to our capital city. This scavenger hunt is all about exploring a side to London you might never have seen before… (all these places are free to visit!) There are 100 Quests - how many can you complete and how many points can you earn? You will need to plan your own route – it will not be possible to complete all the challenges set in one day, but the idea is to choose parts of London you want to explore and complete as many quests as possible. Read through the whole resource before starting out, as there are many quests to choose from and bonus points to earn… Have a great day! The Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt resource was put together by a team of Senior Section leaders in Hampshire North to celebrate The Senior Section Spectacular in 2016. As a county, we used this resource as part of a centenary event with teams of Senior Section from across the county all taking part on the same day. We hope this resource might inspire other similar events or maybe just as a way to explore London on a unit day trip…its up to you! If you would like a badge to mark taking part in this challenge, you can order a Hampshire North County badge designed by members of The Senior Section to celebrate the centenary (see photo below). -

Download Walking People at Your Service London

WALKING PEOPLE AT YOUR SERVICE IN THE CITY OF LONDON In association with WALKING ACCORDING TO A 2004 STUDY, WALKING IS GOOD COMMUTERS CAN EXPERIENCE FOR BUSINESS HAPPIER, MORE GREATER STRESS THAN FIGHTER PRODUCTIVE PILOTS GOING INTO BATTLE WORKFORCE We are Living Streets, the UK charity for everyday walking. For more than 85 years we’ve been a beacon for this simple act. In our early days our campaigning led to the UK’s first zebra crossings and speed limits. 94% SAID THAT Now our campaigns, projects and services deliver real ‘GREEN EXERCISE’ 109 change to overcome barriers to walking and LIKE WALKING JOURNEYS BETWEEN CENTRAL our groundbreaking initiatives encourage IMPROVED THEIR LONDON UNDERGROUND STATIONS MENTAL HEALTH ARE ACTUALLY QUICKER ON FOOT millions of people to walk. Walking is an integral part of all our lives and it can provide a simple, low cost solution to the PHYSICAL ACTIVITY PROGRAMMES increasing levels of long-term health conditions AT WORK HAVE BEEN FOUND TO caused by physical inactivity. HALF REDUCE ABSENTEEISM BY UP TO Proven to have positive effects on both mental and OF LONDON CAR JOURNEYS ARE JUST physical health, walking can help reduce absenteeism OVER 1 MILE, A 25 MINUTE WALK 20% and staff turnover and increase productivity levels. With more than 20 years’ experience of getting people walking, we know what works. We have a range of 10,000 services to help you deliver your workplace wellbeing 1 MILE RECOMMENDED WALKING activities which can be tailored to fit your needs. NUMBER OF DAILY 1 MILE BURNS Think of us as the friendly experts in your area who are STEPS UP TO 100 looking forward to helping your workplace become CALORIES happier, healthier and more productive. -

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES DAVID LONG ONEWORLD A Oneworld Book First published in North America, Great Britain & Austalia by Oneworld Publications 2014 Copyright © David Long 2014 The moral right of David Long to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78074-413-1 ISBN 978-1-78074-414-8 (eBook) Text designed and typeset by Tetragon Publishing Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Croydon, UK Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England CONTENTS Introduction xiii Chapter 1: Roman Londinium 1 1. London Wall City of London, EC3 2 2. First-century Wharf City of London, EC3 5 3. Roman Barge City of London, EC4 7 4. Temple of Mithras City of London, EC4 9 5. Amphitheatre City of London, EC2 11 6. Mosaic Pavement City of London, EC3 13 7. London’s Last Roman Citizen 14 Trafalgar Square, WC2 Chapter 2: Saxon Lundenwic 17 8. Saxon Arch City of London, EC3 18 9. Fish Trap Lambeth, SW8 20 10. Grim’s Dyke Harrow Weald, HA3 22 11. Burial Mounds Greenwich Park, SE10 23 12. Crucifixion Scene Stepney, E1 25 13. ‘Grave of a Princess’ Covent Garden, WC2 26 14. Queenhithe City of London, EC3 28 Chapter 3: Norman London 31 15. The White Tower Tower of London, EC3 32 16. Thomas à Becket’s Birthplace City of London, EC2 36 17. -

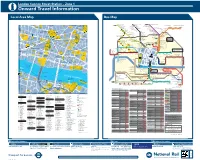

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Palmers Green North Circular Road Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 149 S GRESHAM STREET 17 EDMONTON R 141 1111 Guildhall 32 Edmonton Green 65 Moorgate 12 A Liverpool Street St. Ethelburga’s Centre Wood Green I 43 Colney Hatch Lane Art Gallery R Dutch WALTHAMSTOW F for Reconcilation HACKNEY 10 Church E Upper Edmonton Angel Corner 16 N C A R E Y L A N E St. Lawrence 17 D I and Peace Muswell Hill Broadway Wood Green 33 R Mayor’s 3 T 55 ST. HELEN’S PLACE for Silver Street 4 A T K ING S ’S ARMS YARD Y Tower 42 Shopping City ANGEL COURT 15 T Jewry next WOOD Hackney Downs U Walthamstow E E & City 3 A S 6 A Highgate Bruce Grove RE 29 Guildhall U Amhurst Road Lea Bridge Central T of London O 1 E GUTTER LANE S H Turnpike Lane N St. Margaret G N D A Court Archway T 30 G E Tottenham Town Hall Hackney Central 6 R O L E S H GREEN TOTTENHAM E A M COLEMAN STREET K O S T 95 Lothbury 35 Clapton Leyton 48 R E R E E T O 26 123 S 36 for Whittington Hospital W E LOTHBURY R 42 T T 3 T T GREAT Seven Sisters Lea Bridge Baker’s Arms S T R E E St. Helen S S P ST. HELEN’S Mare Street Well Street O N G O T O T Harringay Green Lanes F L R D S M 28 60 5 O E 10 Roundabout I T H S T K 33 G M Bishopsgate 30 R E E T L R O E South Tottenham for London Fields I 17 H R O 17 Upper Holloway 44 T T T M 25 St. -

2018 Autumn Update – Ward of Cheap Team Working for the City

Our pledges to you ü Improving air quality ü Tackling congestion and road safety for all users ü Promoting diversity and social mobility ü Supporting a vibrant Cheapside business community 2018 Autumn update – Ward of ü Ensuring a safe City, addressing begging and ending rough sleeping Cheap Team working for the City ü Protecting and promoting the City through Brexit Welcome to our Autumn Report updang you on the work as your ü Stewarding the City Corporation’s investment and charity projects local representaves over the last few months. Our first report aer the elec1on CONTACT US INCREASED SUPPORT FOR CITY TRANSPORT STRATEGY of our new Alderman Robert EDUCATION Hughes-Penney. A huge thank As your local representaves We would like to hear from you you to everyone who came out we are here to help and make The City Corporaon and Livery what you think about the City’s to vote in July. Turn out was sure your voice is heard. Companies have historically dra strategy, which will shape strong with 54.9%. Throughout the year we will always been great supporters the City for the next 25 years. keep you informed of our work, of educaon. Today this The plan aims to deliver world- In this report we feedback on key but do feel free to contact us supports con1nues - recently class connec1ons and a SQuare issues we have taken the lead on any1me. strengthened with new City Mile that is accessible to all as a team over the last few skills, appren1ceships and including: months. Your Ward Team (le. -

A Study of London's Transported Female Convicts 1718-1775

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 From Newgate to the New World: a study of London's transported female convicts 1718-1775 Jennifer Lodine-Chaffey The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lodine-Chaffey, Jennifer, "From Newgate to the New World: a study of London's transported female convicts 1718-1775" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9085. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9085 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ^Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: . Date: 5" - M - O C Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Excavations on the Site of St Nicholas Shambles, Newgate Street, City of London, 1975-9

EXCAVATIONS ON THE SITE OF ST NICHOLAS SHAMBLES, NEWGATE STREET, CITY OF LONDON, 1975-9 John Schofield With contributions by Ian M Betts, Tony Dyson, Julie Edwards, Richard Lea, Jacqui Pearce, Alan Thompson and Kieron Tyler SUMMARY World War; in 1974 Victorian buildings (the lower storeys of part of the original structure) The site of the small parish church of St Nicholas and a large circular ventilation shaft occupied Shambles, north of Newgate Street in the City of London the south-west quarter of the site. The eastern was excavated in 1975-9. ^^ church, which was demol half of the site, beyond Roman Bath Street ished in 1552, lay under modern buildings which had (which lay on the line of the medieval Pentecost removed all horizontal levels and only truncated foundations Lane), was already lost to archaeological investi survived. It is suggested that the church had five phases of gation as the cumulative effect of building and development: (i) a nave and chancel in the early nth clearance had removed all deposits. The north century; (ii) an extension of the chancel, probably a sanctu west quarter of the site, west of Roman Bath ary, in the period 1150-1250 or later; (Hi) chapels to Street and north of the church site, was also the north and south of the extended chancel, 1340—1400; excavated in 1975-9 (sitecode POM79), and (iv) a north and south aisle (1400-50, possibly in stages; publication of this excavation is planned for some (v) rebuilding of part of the north wall and a north vestry point in the future.