Digital Complements Or Substitutes? a Quasi-Field Experiment from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Read the 2015/2016 Financial Statement

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 National Theatre Page 1 of 87 PUBLIC BENEFIT STATEMENT In developing the objectives for the year, and in planning activities, the Trustees have considered the Charity Commission’s guidance on public benefit and fee charging. The repertoire is planned so that across a full year it will cover the widest range of world class theatre that entertains, inspires and challenges the broadest possible audience. Particular regard is given to ticket-pricing, affordability, access and audience development, both through the Travelex season and more generally in the provision of lower price tickets for all performances. Geographical reach is achieved through touring and NT Live broadcasts to cinemas in the UK and overseas. The NT’s Learning programme seeks to introduce children and young people to theatre and offers participation opportunities both on-site and across the country. Through a programme of talks, exhibitions, publishing and digital content the NT inspires and challenges audiences of all ages. The Annual Report is available to download at www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/annualreport If you would like to receive it in large print, or you are visually impaired and would like a member of staff to talk through the publication with you, please contact the Board Secretary at the National Theatre. Registered Office & Principal Place of Business: The Royal National Theatre, Upper Ground, London. SE1 9PX +44 (0)20 7452 3333 Company registration number 749504. Registered charity number 224223. Registered in England. Page 2 of 87 CONTENTS Public Benefit Statement 2 Current Board Members 4 Structure, Governance and Management 5 Strategic Report 8 Trustees and Directors Report 36 Independent Auditors’ Report 45 Financial Statements 48 Notes to the Financial Statements 52 Reference and Administrative Details of the Charity, Trustees and Advisors 86 In this document The Royal National Theatre is referred to as “the NT”, “the National”, and “the National Theatre”. -

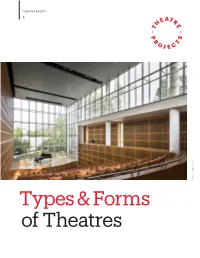

Types & Forms of Theatres

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

Place, Tourism and Belonging

18 The National Theatre, London, as a theatrical/architectural object of fan imagination Matt Hills Introduction Stijn Reijnders has argued that “memory seems to play an important part in the way in which places of the imagination are experienced. In other words, one can identify a certain reciprocity between memory and imagination” ( 2011 : 113). This chapter builds on such a recognition by focusing on the “mnemonic imagination” ( Keightley & Pickering, 2012) within place-making affects. At the same time, I am responding to the question of whether it is “possible to be a fan of a destination?” ( Linden & Linden, 2017 : 110). As Rebecca Williams (2018: 104) has recently argued, we need a greater under- standing of what places can do to visitors who may not bring particular media or fan-specific imaginative expectations with them and yet may respond strongly to a particular place. What confluence of affective, emo- tional and experiential elements may cause them to become fans of that site . .? By focusing on the Royal National Theatre on the South Bank of London – usually referred to as the “National Theatre” or the “NT” – I am deliber- ately taking a case study which multiplies some of these questions, since the NT has acted as the site for both theatre fandom (Hills, 2017 ) and what has been termed “architectural enthusiasm” (Craggs et al., 2013 , 2016 ). Indeed, the National Theatre has been marked by a related doubling through- out its history (having opened in 1976 after a much-delayed construction process). For, as Daniel Rosenthal (2013 : 845) observes in The National Theatre Story , it represents “what [playwright] Tom Stoppard termed co- existent institutions: ‘One was the ideal of a national theatre; the other was the building’”. -

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean Based on the Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with Songs by Grant Olding Background Pack

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with songs by Grant Olding Background pack The National's production 2 Carlo Goldoni 3 Commedia dell'arte 4 One Man, Two Guvnors – a background 5 Lazzi – comic set pieces 7 Characters 9 Rehearsal overview 10 In production: from the Lyttelton to the Adelphi 13 In production: Theatre Royal Haymarket 14 Richard Bean interview 15 Grant Olding Interview 17 Further production detailsls: This background pack is Director Learning Workpack writer www.onemantwoguvnors.com published by and copyright Nicholas Hytner National Theatre Adam Penford The Royal National Theatre South Bank Board London SE1 9PX Editor Reg. No. 1247285 T 020 7452 3388 Ben Clare Registered Charity No. F 020 7452 3380 224223 E discover@ Views expressed in this nationaltheatre.org.uk Rehearsal and production workpack are not necessarily photographs those of the National Theatre Johan Persson National Theatre Learning Background Pack 1 The National’s production The production of One Man, Two Guvnors opened in the National’s Lyttelton Theatre on 24 May 2011, transferring to the Adelphi from 8 November 2011; and to the Theatre Royal Haymarket with a new cast from 2 March 2012. The production toured the UK in autumn 2011 and will tour again in autumn 2012. The original cast opened a Broadway production in May 2012. Original Cast (National Theatre and Adelphi) Current Cast (Theatre Royal Haymarket) Dolly SuzIE TOASE Dolly JODIE PRENGER Lloyd Boateng TREvOR LAIRD Lloyd Boateng DEREk ELROy Charlie -

Conservation Management Plan for the National Theatre Haworth Tompkins

Conservation Management Plan For The National Theatre Final Draft December 2008 Haworth Tompkins Conservation Management Plan for the National Theatre Final Draft - December 2008 Haworth Tompkins Ltd 19-20 Great Sutton Street London EC1V 0DR Front Cover: Haworth Tompkins Ltd 2008 Theatre Square entrance, winter - HTL 2008 Foreword When, in December 2007, Time Out magazine celebrated the National Theatre as one of the seven wonders of London, a significant moment in the rising popularity of the building had occurred. Over the decades since its opening in 1976, Denys Lasdun’s building, listed Grade II* in 1994. has come to be seen as a London landmark, and a favourite of theatre-goers. The building has served the NT company well. The innovations of its founders and architect – the ampleness of the foyers, the idea that theatre doesn’t start or finish with the rise and fall of the curtain – have been triumphantly borne out. With its Southbank neighbours to the west of Waterloo Bridge, the NT was an early inhabitant of an area that, thirty years later, has become one of the world’s major cultural quarters. The river walk from the Eye to the Design Museum now teems with life - and, as they pass the National, we do our best to encourage them in. The Travelex £10 seasons and now Sunday opening bear out the theatre’s 1976 slogan, “The New National Theatre is Yours”. Greatly helped by the Arts Council, the NT has looked after the building, with a major refurbishment in the nineties, and a yearly spend of some £2million on fabric, infrastructure and equipment. -

Ian Gelder Photo: Jonathan Dockar-Drysdale

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] Ian Gelder Photo: Jonathan Dockar-Drysdale Location: London Eye Colour: Brown Height: 5'9" (175cm) Hair Colour: Grey Weight: 10st. 7lb. (67kg) Hair Length: Short Playing Age: 61 - 70 years Voice Character: Authoritative Appearance: White Voice Quality: Warm Other: Equity Stage Stage, Mr Pasmore, The March On Russia, Orange Tree Theatre, Alice Hamilton Stage, Harry Henderson, Racing Demon, Theatre Royal Bath, Jonathan Church Stage, Clifford, The Treatment, Almeida Theatre, Lyndsey Turner Stage, John, Human Animals, Royal Court, Hamish Pirie Stage, James Whale, Gods and Monsters, Southwark Playhouse, Russel Labey Stage, Marcus Andronicus, Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare's Globe, Lucy Bailey Stage, Jack Bryant, Roots, Donmar Warehouse, James Macdonald Stage, Ed, Pugh, Farmer, The Low Road, The Royal Court, Dominic Cooke Stage, Kent, King Lear, Almeida, Michael Attenborough Stage, Frank, Definitely the Bahamas, The Orange Tree, Martin Crimp Stage, Larry, Company, Sheffield Crucible, Jonathan Mumby Stage, George, Precious Little Talent, Trafalgar Studios, James Dacre Stage, Harry, Racing Demon, Crucible Theatre Sheffield, Daniel Evans Stage, Jestin Overton, Lingua Franca, Finborough Theatre, Michael Gieleta Stage, David Freud, The Power of Yes, National Theatre, Angus Jackson Stage, Merrison/Greville Todd/Duckett/Gleason, Serious Money, Birmingham Rep, Jonathan Mumby Stage, Max, The -

Orchestrated Public Space: the Curatorial Dimensions of the Transformation of London's Southbank Centre

Alasdair Jones Orchestrated public space: the curatorial dimensions of the transformation of London's Southbank Centre Book section Original citation: Originally published in: Golchehr, Saba, Ainley, Rosa, Friend, Adrian, Johns, Kathy and Raczynska, Karolina, (eds.) Mediations: Art & Design Agency and participation in public space, conference proceedings. London, UK : Royal College of Art, 2016, pp. 244-257. Reuse of this item is permitted through licensing under the Creative Commons: © 2016 The Author CC-BY-NC 4.0 This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/68373/ Available in LSE Research Online: November 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. ORCHESTRATED PUBLIC SPACE The Curatorial Dimensions Of The Transformation Of London’s Southbank Centre A. Jones Keywords: Public Space, Open Space, Curation, Southbank Centre, Ethnographic ABSTRACT Since 1999, London’s Southbank Centre, an assemblage of arts venues and constituent public spaces in central London, has been undergoing a gradual ‘transformation’ that continues to this day (Southbank Centre, 2016). In addition to works to refurbish the arts venues, this transformation has involved the renewal of the public realm between, around and (most infamously) beneath those venues. Using ethnographic data I seek to unpack the curatorial dimensions of the redesign and reappropriation of public space at this site. 244 1. INTRODUCTION A curious tension characterises contemporary This paper adds to a sparse but growing writing about urban public space. -

V&A Innovative Leadership 2015/16 Programme

V&A Innovative Leadership 2015/16 Programme 14th October 2015 - 20th July 2016 What participants say: “The innovative course is an excellent opportunity to take time out from usual hectic schedules to take stock and focus on vital leadership and management self-development. It also provides tools and material that have immediate value in terms of supporting solutions for organisational challenges, and long term sustainability.” “The programme provided the opportunity I had been looking for – time away from the day job to think hard about my practice as a museum professional, and in turn for my teams. I have come away from the programme inspired.” "In just a year I feel I have come a long way which is what I had hoped when I started the course. The course helped build my confidence and has made me realise my potential. It gave me the confidence to go for a promotion which I have since got." "This programme is refreshingly different from other offers in the UK in going beyond bite-sized management information: management and leadership are explored through inspirational lectures by leaders who provide an authentic insight into their work; several real-life assignments at the V&A and other culture institutions gave my fellow participants and me ample opportunity to practice and gain experience. I have met extraordinary people from institutions across the country, and formed strong links. The action learning sets have been one of the key ingredients in my opinion. My action learning set continues to meet: we learn from each other, and grow together." “It has improved my confidence which has in turn improved my effectiveness in dealing with challenging situations. -

Warhorse: Teacher Resource Guide

Teacher Resource Guide WarHorseWH Title :Page1.12.12_H4 Teacher title Resource page.qxd 12/29/11 Guide 2:21 PM Page 1 by Heather Lester LINCOLN CENTER THEATER AT THE VIVIAN BEAUMONT under the direction of André Bishop and Bernard Gersten NATioNAL THEATRE of GREAT BRiTAiN under the direction of Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr in association with Bob Boyett War Horse LP presents National Theatre of Great Britain production based on the novel by Michael Morpurgo adapted by Nick Stafford in association with Handspring Puppet Company with (in alphabetical order) Stephen James Anthony Alyssa Bresnahan Lute Breuer Hunter Canning Anthony Cochrane Richard Crawford Sanjit De Silva Andrew Durand Joel Reuben Ganz Ben Graney Alex Hoeffler Leah Hofmann Ben Horner Brian Lee Huynh Jeslyn Kelly Tessa Klein David Lansbury Tom Lee Jonathan Christopher MacMillan David Manis Jonathan David Martin Nat Mcintyre Andy Murray David Pegram Kate Pfaffl Jude Sandy Tommy Schrider Hannah Sloat Jack Spann Zach Villa Elliot Villar Enrico D. Wey isaac Woofter Katrina Yaukey Madeleine Rose Yen sets, costumes & drawings puppet design, fabrication and direction lighting Rae Smith Adrian Kohler with Basil Jones Paule Constable for Handspring Puppet Company director of movement and horse movement animation & projection design Toby Sedgwick 59 Productions music songmaker sound music director Adrian Sutton John Tams Christopher Shutt Greg Pliska associate puppetry director artistic associate production stage manager casting Mervyn Millar Samuel Adamson Rick Steiger Daniel Swee NT technical producer NT producer NT associate producer NT marketing Boyett Theatricals producer Katrina Gilroy Chris Harper Robin Hawkes Karl Westworth Tim Levy executive director of managing director production manager development & planning director of marketing general press agent Adam Siegel Jeff Hamlin Hattie K. -

Opera & Music | Spring 2014

OPERA & MUSIC | SPRING 2014 THE ROYAL OPERA REPERTORY PAGE DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN 2 THE COMMISSION / CAFÉ KAFKA 4 L’ORMINDO (AT SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE) 6 THROUGH HIS TEETH 7 THE CRACKLE 8 FAUST 9 JONAS KAUFMANN – WINTERREISSE 11 LA TRAVIATA 12 LE NOZZE DI FIGARO 14 TOSCA 15 DIALOGUES DES CARMÉLITES 17 BABYO / SENSORYO 19 LUNCHTIME RECITALS AND EVENTS 21 PRESS OFFICE CONTACTS 24 For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/press DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN NEW PRODUCTION Richard Strauss 14, 17, 20, 26, 29 March at 6pm; 23 March at 3pm 2 April at 6pm • Co-production with La Scala, Milan. • Generously supported by Sir Simon and Lady Robertson, Hamish and Sophie Forsyth, The Friends of Covent Garden and an anonymous donor. • Die Frau ohne Schatten will be broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 on 29 March 2014 at 5.45pm. The Royal Opera celebrates the 150th anniversary of Strauss’s birth with a new production of Die Frau ohne Schatten , one of three Strauss operas being presented at the Royal Opera House this Season, all with librettos by Hugo von Hofmannsthal on mythical themes. Elektra was revived in October 2013 and Ariadne auf Naxos will be revived in June 2014. This production of Die Frau ohne Schatten is new to the Royal Opera House, and is a co-production with La Scala, Milan, where it was first seen in 2012. German director Claus Guth makes his UK and Royal Opera debut with this production, which explores themes of the search for identity and the psychological power of dreams, and vividly illustrates the plight of the central character of the Empress, a woman trapped between two repressive worlds. -

International Theatre Programs Collection O-018

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8b2810r No online items Inventory of the International Theatre Programs Collection O-018 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis General Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2017 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/special-collections/ Inventory of the International O-018 1 Theatre Programs Collection O-018 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis General Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: International Theatre Programs Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-018 Physical Description: 19.1 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1884-2011 Abstract: Mostly 19th and early 20th century British programs, including a sizable group from Dublin's Abbey Theatre. Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Scope and Contents The collection includes mostly 19th and early 20th century British programs, including a sizable group from Dublin's Abbey Theatre. Access Collection is open for research. Processing Information Liz Phillips converted this collection list to EAD. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], International Theatre Program Collection, O-018, Department of Special Collections, General Library, University of California, Davis. Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items.