Backgrounds of Mps and Msps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Risk Management Strategy Forth Estuary Local Plan

Flood Risk Management Strategy Forth Estuary Local Plan District This section provides supplementary information on the characteristics and impacts of river, coastal and surface water flooding. Future impacts due to climate change, the potential for natural flood management and links to river basin management are also described within these chapters. Detailed information about the objectives and actions to manage flooding are provided in Section 2. Section 3: Supporting information 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 379 3.2 River flooding ......................................................................................... 380 East Lothian and Berwickshire catchment group .............................. 381 Almond and Edinburgh catchment group.......................................... 390 Firth of Forth catchment group ......................................................... 400 3.3 Coastal flooding ...................................................................................... 408 3.4 Surface water flooding ............................................................................ 418 Forth Estuary Local Plan District Section 3 378 3.1 Introduction In the Forth Estuary Local Plan District, river flooding is reported across two distinct river catchments. Coastal flooding and surface water flooding are reported across the whole Local Plan District. A summary of the number of properties and Annual Average Damages from river, coastal and surface water -

Rail for All Report

RAIL FOR ALL Delivering a modern, zero-carbon rail network in Scotland Green GroupofMSPs Policy Briefing SUMMARY Photo: Times, CC BY-SA 2.5 BY-SA Times, CC Photo: The Scottish Greens are proposing the Rail for All investment programme: a 20 year, £22bn investment in Scotland’s railways to build a modern, zero-carbon network that is affordable and accessible to all and that makes rail the natural choice for commuters, business and leisure travellers. This investment should be a central component of Scotland’s green recovery from Covid, creating thousands of jobs whilst delivering infrastructure that is essential to tackle the climate emergency, that supports our long-term economic prosperity, and that will be enjoyed by generations to come. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1 Creating the delivery infrastructure 4 i. Steamline decision-making processes and rebalance 4 them in favour of rail ii. Create one publicly-owned operator 4 iii. Make a strategic decision to deliver a modern, 5 zero-carbon rail network and align behind this iv. Establish a task force to plan and steer the expansion 5 and improvement of the rail network 2 Inter-city services 6 3 Regional services 9 4 Rural routes and rolling stock replacement 10 5 TramTrains for commuters and urban connectivity 12 6 New passenger stations 13 7 Reopening passenger services on freight lines 14 8 Shifting freight on to rail 15 9 Zero-carbon rail 16 10 Rail for All costs 17 11 A green recovery from Covid 18 This briefing is based on the report Rail for All – developing a vision for railway investment in Scotland by Deltix Transport Consulting that was prepared for John Finnie MSP. -

City of Edinburgh Local Government

Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland PUBLIC CONSULTATION ward boundary proposals in City of Edinburgh Crown Copyright and database right 2015. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey licence no. 100022179 4 13 1 12 5 14 11 3 6 17 7 15 9 10 16 no. 8 ward no. ward name councillors 1 Almond 4 2 Pentland Hills 4 2 3 Drum Brae / Gyle 3 4 Forth 4 5 Inverleith 4 6 Corstorphine / Murrayfield 3 7 Sighthill / Gorgie 4 8 Colinton / Fairmilehead 3 9 Fountainbridge / Craiglockhart 3 10 Morningside 4 11 City Centre 4 12 Leith Walk 4 13 Leith 3 14 Craigentinny / Duddingston 4 1 proposed ward number 15 Southside / Newington 4 proposed ward 16 Gilmerton 4 0 3 miles 17 Portobello / Craigmillar 4 total 63 ± 0 3 km Background How to comment on our ward boundary proposals We are undertaking a 12 week period of public consultation on proposed ward We need you to tell us what you think of our proposals boundaries for each council area in Scotland as part of our Fifth Reviews of via our interactive consultation portal at Electoral Arrangements. www.consultation.lgbc-scotland.gov.uk or by emailing Legislation says that we must conduct electoral reviews of each local authority or writing to us at the address below. at intervals of 8 to 12 years. For further background on the Commission and this Our proposals and further information are available in review please visit our website. this building and also on our website. Please submit City of Edinburgh ward boundary proposals your comments by 22 October 2015 Our proposals for wards in City of Edinburgh council area present an electoral arrangement for 63 councillors representing 5 3-member wards and 12 4-member wards, Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland Thistle House increasing councillor numbers in the area by 5. -

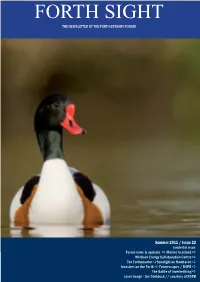

Forth Sight the Newsletter of the Forth Estuary Forum

FORTH SIGHT THE NEWSLETTER OF THE FORTH ESTUARY FORUM Summer 2011 / Issue 22 Inside this issue: Forum news & updates D Marine Scotland D 1. hellhe Whitlock Energy Collaboration Centre D The Forthquarter DSpotlight on Newhaven D Invasives on the Forth D Futurescapes / RSPB D The Battle of Inverkeithing D cover image - the Shelduck // courtesy of RSPB FORTH SIGHT Welcome 2 Welcome from Ruth Briggs, Chair of the Forth Estuary Forum This time last year we could be forgiven 3 Forthsight for wondering whether we would still have a Forum as strong as we have just now. 4 Forum News We had no guarantees of funding for the Marine Planning in Scotland current year, pressure on all our sponsors’, members’ and supporters’ budgets and 5 The ForthQuarter an uncertain view of the role of coastal 6 Invasives partnerships in the then equally uncertain political and economic times. 7 RSPB Futurescapes Well, here we are, actively engaged in key 8 Whitlock Energy Collaboration Forth issues from Government to local level, maintaining our focus on promoting under- Centre standing and collaboration among users and authorities relevant to the Forth, with a keen eye to the future both of the Forth Estuary and its Forum. Management and planning for 9-10 Focus on Newhaven maritime environments is high on the Scottish Government’s agenda and we are ideally placed to facilitate and contribute to getting it right for the Forth. 11 The Battle of Inverkeithing Running the Forum costs a minimum of about £60,000 a year, a modest fi gure used thrift- ‘Forth Sight’ is a bi-annual publication on all matters ily by our staff and board of directors. -

Sighthill / Gorgie) High Proportion of Council Tenants

LOCALITY SERVICE AREA SIZE OF SECTOR/CHALLENGES /ASPIRATIONS FOR SERVICE USERS SOUTH WEST Total population: Smallest 16+ population: 94,093 109,245 Health Wards: Age: 0-15: 17,381 Relatively low proportion of residents with long term health problems that limit day to day Pentland Hills; Sighthill / Age: 65+ : 15,310 activities Gorgie; Highest percentage of residents economically inactive due to limiting long term illness (15%) Fountainbridge / Relatively high rates of women with dementia, but low concentration among men Health and Social Care Craiglockhart; Highest proportion of Health and Social care open cases in under 24 year age group Colinton / Fairmilehead Low take up of direct payments. Lowest concentration of people providing unpaid care NEIGHBOURHOOD Highest concentration of people who cycle to work PARTNERSHIPS (2) General South West NP Most like Edinburgh as a whole Pentlands NP Most deprived individual ward (Sighthill / Gorgie) High proportion of council tenants Lower than average proportion of social renters VSF Most deprived single ward (Sighthill / Gorgie) Significant levels of localised income inequality SW and Pentlands High proportion of economic inactivity due to long term limiting illness SOUTH EAST/CENTRAL Total population: 124,930 Second largest population: 126,148 Age 0-15: 15,745 Largest proportion of persons aged 16 – 24 (40.3%) (students) Wards: Age: 65+ : 16,024 Highest concentration of people aged 85+ City Centre; Liberton / Health The only locality showing an increase (albeit small) in stroke-related -

Fuel Poverty Mapping of the City of Edinburgh

Fuel Poverty Mapping of the City of Edinburgh Estimated fuel poverty density in City of Edinburgh Council May 2015 Changeworks 36 Newhaven Road Edinburgh, EH6 5PY T: 0131 555 4010 E: [email protected] W: www.changeworks.org.uk/consultancy Fuel Poverty Mapping of the City of Edinburgh for the City Report of Edinburgh Council Katie Ward, Senior Project Manager. Main contact [email protected]; 0131 529 7112. Henry Russell T: 0131 539 8579 E: [email protected] Issued by Changeworks Resources for Life Ltd Charity Registered in Scotland (SCO15144) Company Number (SC103904) VAT Registration Number (927106435) Approved by Ruth Williamson, Principal Consultant. All contents of this report are for the exclusive use of Changeworks and the City of Edinburgh Council. Fuel Poverty Mapping of the City of Edinburgh 2 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 5 2. CONTEXT .......................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Fuel Poverty in Edinburgh ........................................................................... 5 3. RESULTS .......................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Fuel Poverty Map Overview ........................................................................ 8 3.2 Fuel poverty by multi-member -

Police and Fire Scrutiny Committee

Police and Fire Scrutiny Committee 10.00am, Friday, 6 February 2015 SCOTTISH FIRE AND RESCUE SERVICE (SFRS), CITY OF EDINBURGH PERFORMANCE REPORT, YEAR TO DATE DECEMBER 2014 Item number Report number Executive/routine Wards All Executive summary This report covers the year to date performance report, in a new format provided from the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service (SFRS) performance function, and the City of Edinburgh Prevention and Protection year to date report, to December 2014. The new format has been developed to provide a consistent and accurate reporting framework, allowing the Local Senior Officer to provide the Scrutiny Committee with appropriate performance data measured against the priorities in the Local Fire Plan, complimented with the Prevention and Protection outputs and performance against nationally set targets. Links Coalition pledges Council outcomes Single Outcome Agreement Report SCOTTISH FIRE AND RESCUE SERVICE, CITY OF EDINBURGH PERFORMANCE REPORT, YEAR TO DATE DECEMBER 2014 Recommendations 1.1 The Committee is asked to note the contents of the report and the attached SFRS City of Edinburgh year to date performance and Prevention and Protection reports covering the period April to December 2014. Background 2.1 As the SFRS develops and improves the availability of accurate and timeous data to meet local scrutiny this will continue to make changes to the reports provided. Main report 3.1 The last two quarterly performance reports, quarter 1 and 2 2014, had used a previously agreed format but had used nationally provided data for the first time. 3.2 Work has progressed to develop a nationally provided performance report template providing a high level of accurate local data to demonstrate outcomes against local plan priorities. -

THE NEWHAVEN CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL the NEWHAVEN CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL WAS APPROVED by the PLANNING COMMITTEE on 11Th MAY 2000

THE NEWHAVEN CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL THE NEWHAVEN CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL WAS APPROVED BY THE PLANNING COMMITTEE ON 11th MAY 2000 2 T HE NEWHAVEN CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 Conservation Areas 2 Character Appraisals 2 Newhaven Conservation Area 2 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 4 Origins 4 Growth of the Village 5 Twentieth Century 6 KEY ELEMENTS AND ANALYSIS 7 Introduction 7 ESSENTIAL CHARACTER 8 ZONE 1: HISTORIC CORE 8 Spatial Pattern and Townscape 8 Buildings and Materials 9 Open Spaces 10 Circulation 11 ZONE 1 : ESSENTIAL CHARACTER 12 ZONE 2 : RESIDENTIAL ZONE 13 Spatial Pattern and Townscape 13 Buildings and Materials 14 Open Spaces 14 Circulation 15 ZONE 2 : ESSENTIAL CHARACTER 15 OPPORTUNITIES FOR ENHANCEMENT 16 GENERAL INFORMATION 17 Statutory Policies Relating to Newhaven 17 Supplementary Guidelines 17 Implications of Conservation Area Status 18 Protection of Trees 19 Grants for Conservation 19 The Role of the Public 19 REFERENCES 20 1 T HE NEWHAVEN CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL INTRODUCTION Conservation Areas Section 61 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) (Scotland) Act 1997, describes conservation areas as “...areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance”. The Act makes provision for the designation of conservation areas as distinct from individual buildings, and planning authorities are required to determine which parts of their areas merit conservation area status. There are currently 38 conservation areas in Edinburgh, including city centre areas, Victorian suburbs and former villages. Each conservation area has its own unique character and appearance. Character Appraisals The protection of an area does not end with conservation area designation; rather designation demonstrates a commitment to positive action for the safeguarding and enhancement of character and appearance. -

Leith Docks Development Framework

Leith Docks Development Framework Contents 0 Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 3 Description of LDDF Area 4 Planning Policy - Overview 5 Infrastructure Issues: Engineering 6 Potential Land Uses 7 LDDF Proposals – Access and Accessibility 2 Leith Docks Development Framework Supplementary Planning Guidance 8 LDDF Proposals – Environment and Sustainability 9 LDDF Proposal – Urban Planning and Public Realm - Figures 1.01 to 1.24 10 LDDF Proposal (including Figures 2.01 to 2.22) 11 Implementation Annex A LDDF Sustainability Targets Annex B Masterplan Consultation Groups Supplementary Planning Guidance Leith Docks Development Framework 3 4 Leith Docks Development Framework Supplementary Planning Guidance Supplementary Planning Guidance Leith Docks Development Framework 5 Executive Summary Introduction 0.1 0.2 The framework addresses an area of This document sets out a long-term vision and framework approximately 170 hectares covering Leith for the phased redevelopment of Leith docks in docks, in Forth Ports’ ownership, and the surrounding area, including part of the historic Edinburgh. It has been prepared in initial form by core of Leith. The overarching objective of the consultants for Forth Ports plc within a context set by the vision for this area is as follows: To provide an extension of Leith and the city City of Edinburgh Council and subsequently edited by the which integrates the old and new areas in a mixed, balanced and inclusive waterfront Council both prior to and following a public consultation community while responding to contemporary process. It was approved by the Council as aspirations, concerns and ideas regarding urban planning. supplementary planning guidance on 10 February 2005. -

EDINBURGH 03.Indd

Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland Fourth Statutory Review of Electoral Arrangements City of Edinburgh Council Area Report E06012 Report to Scottish Ministers July 2006 Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland Fourth Statutory Review of Electoral Arrangements City of Edinburgh Council Area Constitution of the Commission Chairman: Mr John L Marjoribanks Deputy Chairman: Mr Brian Wilson OBE Commissioners: Professor Hugh M Begg Dr A Glen Mr K McDonald Mr R Millham Report Number E06012 July 2006 City of Edinburgh Council Area 1 Local Government Boundary Commission for Scotland 2 City of Edinburgh Council Area Fourth Statutory Review of Electoral Arrangements Contents Page Summary Page 7 Part 1 Background Pages 9 – 14 Paragraphs Origin of the Review 1 The Local Governance (Scotland) Act 2004 2 – 4 Commencement of the 2004 Act 5 Directions from Scottish Ministers 6 – 9 Announcement of our Review 10 – 16 General Issues 17 – 18 Defi nition of Electoral Ward Boundaries 19 – 24 Electorate Data used in the Review 25 – 26 Part 2 The Review in City of Edinburgh Council Area Pages 15 –30 Paragraphs Meeting with The City of Edinburgh Council 1 – 3 Concluded View of the Council 4 Aggregation of Existing Wards 5 – 8 Initial Proposals 9 – 11 Informing the Council of our Initial Proposals 12 – 13 The City of Edinburgh Council Response 14 – 15 Consideration of the Council Response to the Initial Proposals 16 Provisional Proposals 17 – 21 Representations 22 Consideration of Representations 23 – 50 Part 3 Final Recommendation Pages 31 -

Flood Risk Management Strategies

Water of Leith catchment (Potentially Vulnerable Area 10/18) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Forth Estuary The City of Edinburgh Water of Leith Council, Midlothian Council Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • 3,300 residential properties • 480 non-residential properties • £5.8 million Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency -

Ward 4 Forth

COUNCIL ELECTION - 3 MAY 2007 WARD 4 FORTH Electorate 20744 Votes cast 11083 Turnout (%) 53.4 Sucessful Candidates Name Party Elected at stage number Allan JACKSON* Scottish Conservative and Unionist One Elaine Patricia MORRIS Scottish Liberal Democrats Seven Elizabeth MAGINNIS* Scottish Labour Party Nine Steve CARDOWNIE* Scottish National Party (SNP) One Candidates on ballot paper Share of First Preference Vote Name Party First Preference Vote (%) Willie BLACK Solidarity - Tomy Sheridan 197 1.8 Steve CARDOWNIE* Scottish National Party (SNP) 2472 22.7 Billy FITZPATRICK* Scottish Labour Party 1547 14.2 Allan JACKSON* Scottish Conservative and Unionist 2206 20.2 Kate JOESTER Scottish Green Party 627 5.8 Elizabeth MAGINNIS* Scottish Labour Party 1616 14.8 Fred MARINELLO Independent 201 1.8 Elaine Patricia MORRIS Scottish Liberal Democrats 1953 17.9 Marilyn SANGSTER Scottish Socialist Party 84 0.8 Total Valid First Preference votes cast 10903 Rejected papers 180 COUNCIL ELECTION - 3 MAY 2007 % Share of First Preference Vote (%) Forth Ward 35.0 30.0 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 Scottish Labour Scottish National Scottish Scottish Liberal Scottish Green Fred Marinello Solidarity - Tomy Scottish Socialist Party Party (SNP) Conservative and Democrats Party (Independent) Sheridan Party Unionist es Full Result Sheet (printable version) » Forth Election For FINAL REPORT Date 04/05/2007 Number to be elected 4 Valid Votes 10903 Rejected as void 180 Quota 2181 Name eSTV Version 2.0.16 Software Registration 1711192147 Rules WIG Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4