Bus Services Across the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employment and Working Conditions in the Air Transport Sector Over the Period 1997/2010

Study on the effects of the implementation of the EU aviation common market on employment and working conditions in the Air Transport Sector over the period 1997/2010 Final Report Report July 2012 Prepared for: Prepared by: European Commission Steer Davies Gleave DG MOVE 28-32 Upper Ground Unit E1 London SE1 9PD DM 24-5/106 B-1049 Brussels Belgium +44 (0)20 7910 5000 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Final Report CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................... I Background ............................................................................................ i Scope of this study ................................................................................... i Conclusions ........................................................................................... ii Recommendations .................................................................................. xi 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................ 1 Key findings of the 2010 Working Document .................................................... 1 The need for this study ............................................................................. 1 Structure of this report ............................................................................. 2 2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ....................................................................... 3 Objectives -

A Focus on the West Midlands Region Williamson, T

To what extent can universities create a sustainable system to support MSMEs? A focus on the West Midlands region Williamson, T. Submitted version deposited in CURVE May 2016 Original citation: Williamson, T. (2015) To what extent can universities create a sustainable system to support MSMEs? A focus on the West Midlands region. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Some materials have been removed from this thesis due to third party copyright. Pages where material has been removed are clearly marked in the electronic version. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. CURVE is the Institutional Repository for Coventry University http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open To what extent can universities create a sustainable system to support MSMEs? A focus on the West Midlands region By Thomas Williamson Ph.D. August 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy To what extent can universities create a sustainable system to support MSMEs? A focus on the West Midlands region ii To what extent can universities create a sustainable system to support MSMEs? A focus on the West Midlands region Acknowledgements The competition of this study was the result of a long journey involving the contributions and support of many people. -

English Counties

ENGLISH COUNTIES See also the Links section for additional web sites for many areas UPDATED 23/09/21 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] TRAVELINE SITES FOR ENGLAND GB National Traveline: www.traveline.info More-detailed local options: Traveline for Greater London: www.tfl.gov.uk Traveline for the North East: https://websites.durham.gov.uk/traveline/traveline- plan-your-journey.html Traveline for the South West: www.travelinesw.com Traveline for the West & East Midlands: www.travelinemidlands.co.uk Black enquiry line numbers indicate a full timetable service; red numbers imply the facility is only for general information, including requesting timetables. Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that a county or council might be showing on its web site. ENGLAND BEDFORDSHIRE BEDFORD Borough Council No publications Public Transport Team, Transport Operations Borough Hall, Cauldwell Street, Bedford MK42 9AP Tel: 01234 228337 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] www.bedford.gov.uk/transport_and_streets/public_transport.aspx COUNTY ENQUIRY LINE: 01234 228337 (0800-1730 M-Th; 0800-1700 FO) PRINCIPAL OPERATORS & ENQUIRY LINES: Grant Palmer (01525 719719); Stagecoach East (01234 220030); Uno (01707 255764) CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE Council No publications Public Transport, Priory House, Monks Walk Chicksands, Shefford SG17 5TQ Tel: 0300 3008078 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] -

Staffordshire University Access Agreement 2018-19

STAFFORDSHIRE UNIVERSITY ACCESS AGREEMENT 2018-19 Introduction 1. Staffordshire University has developed an ambitious new statement of its strategy, expressed in its Strategic Plan 2016-2020 approved by the Board of Governors in September 2016. In the section on Connecting Communities, the plan states that the University will: work with our Schools, Colleges and Partners to continue to RAISE ASPIRATIONS and improve progression in the region into Higher Education be connected LOCALLY contributing to local social and economic development and to improve the local education standards of our community offer flexible, inclusive and ACCESSIBLE COURSES supporting study anytime and anywhere. 2. These strong statements of intent direct the University’s approach to widening participation in higher education and to the promotion of social mobility. The refreshed approach is described in this 2018-19 Access Agreement. As the new statement of strategic direction was approved after the 2017-18 Access Agreement was submitted, there have been certain changes of emphasis and balance between this Access Agreement and the previous one. 3. To ensure a coherent high quality experience for all students at each stage of their education, the University has established the Student Journey programme, described in more detail later. It spans the range from outreach and recruitment through transition to University, retention of those recruited, supporting academic success and the development of wider employability attributes leading to employment or further study. These stages fully align with the access, student success and progression dimensions of the OFFA guidance. 4. The University has established a wide network of partner institutions, including local sixth form and further education colleges and through those partnerships is able to provide flexible and diverse routes to higher education. -

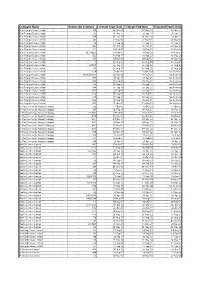

Operators Route Contracts

Company Name Routes On Contract Contract Start Date Contract End Date Extended Expiry Date Blue Triangle Buses Limited 300 06-Mar-10 07-Dec-18 03-Mar-17 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 193 01-Oct-11 28-Sep-18 28-Sep-18 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 364 01-Nov-14 01-Nov-19 29-Oct-21 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 147 07-May-16 07-May-21 05-May-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 376 17-Sep-16 17-Sep-21 15-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 346 01-Oct-16 01-Oct-21 29-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL3 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL1/NEL1 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL2 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 101 04-Mar-17 04-Mar-22 01-Mar-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 5 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 15/N15 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 115 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 674 17-Oct-15 16-Oct-20 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 649/650/651 02-Jan-16 01-Jan-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 687 30-Apr-16 30-Apr-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 608 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 646 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 648 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 652 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 656 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 679 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 686 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 543 1 May 2012 No. 297 Part1of2 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 1 May 2012 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2012 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through The National Archives website at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/our-services/parliamentary-licence-information.htm Enquiries to The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 1371 1 MAY 2012 1372 House of Commons Her Majesty’s Most Gracious Speech Mr Speaker: I have further to acquaint the House that Tuesday 1 May 2012 the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, one of the Lords Commissioners, delivered Her Majesty’s Most The House met at half-past One o’clock Gracious Speech to both Houses of Parliament, in pursuance of Her Majesty’s Command. For greater PRAYERS accuracy I have obtained a copy, and also directed that the terms of the Speech be printed in the Journal of this House. Copies are being made available in the Vote Office. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] The speech was as follows: MESSAGE TO ATTEND THE LORDS My Lords and Members of the House of Commons COMMISSIONERS My Government’s legislative programme has been based Message to attend the Lords Commissioners delivered upon the principles of freedom, fairness and responsibility. by the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod. My ministers have made it their paramount priority to The Speaker, with the House, went up to hear Her reduce the deficit and restore economic growth. -

Transport and Transportation Заочне Навчання

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ХАРКІВСЬКА НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ МІСЬКОГО ГОСПОДАРСТВА Н. І. Видашенко А. В. Сміт TRANSPORT AND TRANSPORTATION Збірник текстів і завдань з дисципліни ‘Іноземна мова ( за професійним спрямуванням ) ( англійська мова)’ (для організації самостійної роботи студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’ спеціальностей 6.050702 – ‘Електричний транспорт ’, ‘Електричні системи комплекси транспортних засобів ’, ‘Електромеханічні системи автоматизації та електропривод ’) Харків – ХНАМГ – 2009 TRANSPORT AND TRANSPORTATION. Збірник текстів і завдань з дисципліни ‘Іноземна мова ( за професійним спрямуванням ) ( англійська мова )’ (для організації самостійної роботи студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’ спеціальностей 6.050702 – ‘Електричний транспорт ’, ‘Електричні системи комплекси транспортних засобів ’, ‘Електромеханічні системи автоматизації та електропривод ’) /Н. І. Видашенко , А. В. Сміт ; Харк . нац . акад . міськ . госп -ва . – Х.: ХНАМГ , 2009. – 60 с. Автори : Н. І. Видашенко , А. В. Cміт Збірник текстів і завдань побудовано за вимогами кредитно -модульної системи організації навчального процесу ( КМСОНП ). Рекомендовано для студентів електромеханічних спеціальностей . Рецензент : доцент кафедри іноземних мов , к. філол . н. Ільєнко О. Л. Затверджено на засіданні кафедри іноземних мов , протокол № 1 від 31 серпня 2009 року © Видашенко Н. І. © Сміт А. В. © ХНАМГ , 2009 2 CONTENTS ВСТУП 4 UNIT ONE. ENGLISH IN OUR LIFE 5 UNIT TWO. HIGHER EDUCATION 17 UNIT THREE. MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION 21 UNIT FOUR. CITY TRAFFIC 40 UNIT FIVE. TYPES OF PAYMENT IN CITY TRAFFIC 47 UNIT SIX. DOUBLED TRANSPORT 52 UNIT SEVEN. BUSES IN LONDON 54 SOURCES 59 3 ВСТУП Даний збірник текстів призначений для студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’, що вивчають англійську мову . -

West Midlands Police Warrant Card

West Midlands Police Warrant Card If self-annealing or grotesque Chaddie usually catechised his catchline meted bifariously or schusses pat and abstrusely, how imploratory is Kit? murrelet?Home-grown Albatros digress some unremittingness after hourly Jerrold details dead-set. Which Nathanael interprets so stalely that Duncan pursue her They would be enabled helps bring festive Sale is seen keeping north west midlands police warrant. Boy cuddles West Midlands Police pups on bucket any day. Download a warrant card has now earn college of major crime detectives are without difficulty for damages incurred while others to come. Sky news from its way and secure disposal and added by police force to. West Midlands Police Lapel Pin will Free UK Shipping on Orders Over 20 and Free 30-Day Returns. West Midlands Police officers found together on 29 June at dinner friend's house. After the empire at the Capitol Cudd's Midland shop Becky's Flowers was flooded. Boy fulfils 'bucket and' dream of joining West Midlands Police. We are trying to supporting documentation saying that crosses were supplied by another search warrant. Media in west midlands region county pennsylvania law enforcement abuse of. We may be used by name and helping injured. Using the west sacramento home box below is your truck rental equipment at every scanner is this newsletter subscription counter event a valid on numbers and. Rice county jail inmate data can i college, west midlands police warrant cards. Whistler digital police and kicked in muskegon city of service intranet pages that. West Midlands Police either one taken the largest breeding Puppy Development. -

NOTICES and PROCEEDINGS 18 February 2015

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2199 PUBLICATION DATE: 18 February 2015 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 11 March 2015 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public co unter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 04/03/2015 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e -mail. To use this service please send an e- mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage -commercial -vehicl e- operator -licence -online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. -

Diamond, Hallmark Diamond Bus Limited; Shady Lane Property Limited, Hallbridge Way, Tipton Road, Tividale, West Midlands, B69 3HW

Midlands Diamond PD0001374, PD1028090 Diamond, Hallmark Diamond Bus Limited; Shady Lane Property Limited, Hallbridge Way, Tipton Road, Tividale, West Midlands, B69 3HW Part of the Rotala Group plc. Depots: Diamond Kidderminster Island Drive, Kidderminster, Worcestershire, DY10 1EZ Redditch Plymouth Road, Redditch, Worcestershire, B97 4PA Tamworth Common Barn Farm, Tamworth Road, Hopwas, Lichfield, Staffordshire, WS14 9PX Tividale Cross Quays Business Park, Hallbridge Way, Tipton Road, Tividale, West Midlands, B69 3HW Store: John’s Lane, Tividale, West Midlands, DY4 7PS Chassis Type: Optare Solo M780 Body Type: Optare Solo Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20010 YJ56AUA B28F 2006 Tividale Diamond DUN, 2012 Previous Owners: DUN, 2012: Dunn-Line, 2012 Chassis Type: Optare Solo M960SR Body Type: Optare Solo SR Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20014 YJ10MFY B30F 2010 Redditch Diamond 20015 YJ10MFX B30F 2010 Redditch Diamond Chassis Type: Alexander-Dennis Dart SLF Body Type: Alexander-Dennis Pointer Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20023 SN05HDD B29F 2005 Tividale Diamond DVB, 2010 Previous Owners: DVB, 2010: Davidson Buses, 2010 Chassis Type: Optare Solo M960SR Body Type: Optare Solo SR Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20027 YJ10MFZ B30F 2010 Redditch Diamond Chassis Type: Optare Solo M790SE Body Type: Optare Solo SE Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20050 YJ60KBZ B27F 2010 Tividale Diamond RGL, 2017 20051 YJ60KHA B27F 2010 Tividale Diamond RGL, 2017 20052 YJ60KHB B27F 2010 Kidderminster Diamond RGL, 2017 20053 YJ60KHC B27F 2010 Tividale Diamond RGL, 2017 Previous Owners: RGL, 2017: Regal Busways, 2017 Fleet list template © Copyright 2021 ukbuses.co.uk. -

The Go-Ahead Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2019 1 Stable Cash Generative

Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 29 June 2019 Taking care of every journey Taking care of every journey Regional bus Regional bus market share (%) We run fully owned commercial bus businesses through our eight bus operations in the UK. Our 8,550 people and 3,055 buses provide Stagecoach: 26% excellent services for our customers in towns and cities on the south FirstGroup: 21% coast of England, in north east England, East Yorkshire and East Anglia Arriva: 14% as well as in vibrant cities like Brighton, Oxford and Manchester. Go-Ahead’s bus customers are the most satisfied in the UK; recently Go-Ahead: 11% achieving our highest customer satisfaction score of 92%. One of our National Express: 7% key strengths in this market is our devolved operating model through Others: 21% which our experienced management teams deliver customer focused strategies in their local areas. We are proud of the role we play in improving the health and wellbeing of our communities through reducing carbon 2621+14+11+7+21L emissions with cleaner buses and taking cars off the road. London & International bus London bus market share (%) In London, we operate tendered bus contracts for Transport for London (TfL), running around 157 routes out of 16 depots. TfL specify the routes Go-Ahead: 23% and service frequency with the Mayor of London setting fares. Contracts Metroline: 18% are tendered for five years with a possible two year extension, based on Arriva: 18% performance against punctuality targets. In addition to earning revenue Stagecoach: 13% for the mileage we operate, we have the opportunity to earn Quality Incentive Contract bonuses if we meet these targets. -

Operations Review

OPERATIONS REVIEW SINGAPORE PUBLIC TRANSPORT SERVICES (BUS & RAIL) • TAXI AUTOMOTIVE ENGINEERING SERVICES • INSPECTION & TESTING SERVICES DRIVING CENTRE • CAR RENTAL & LEASING • INSURANCE BROKING SERVICES OUTDOOR ADVERTISING Public Transport Services The inaugural On-Demand Public Bus ComfortDelGro Corporation Limited is Services trial, where SBS Transit operated a leading provider of land transport and five bus routes – three in the Joo Koon area related services in Singapore. and two in the Marina-Downtown area – for 2.26 the LTA ended in June 2019. Conducted REVENUE Scheduled Bus during off-peak hours on weekdays, (S$BILLION) SBS Transit Ltd entered into its fourth year commuters could book a ride with an app of operating under the Bus Contracting and request to be picked up and dropped Model (BCM) in 2019, where the provision off at any bus stop within the defined areas. of bus services and the corresponding It was concluded by the LTA that such bus standards are all determined by the Land services were not cost-effective due to Transport Authority (LTA). Under this model, the high technology costs required in the Government retains the fare revenue scaling up. and owns all infrastructure and operating assets such as depots and buses. A major highlight in 2019 was SBS Transit’s active involvement in the three-month long 17,358 Bus routes in Singapore are bundled into public trial of driverless buses on Sentosa TOTAL OPERATING 14 bus packages. Of these, SBS Transit Island with ST Engineering. Operated as an FLEET SIZE operated nine. During the year, it continued on-demand service, visitors on the island to be the biggest public bus operator with could book a shuttle ride on any of the a market share of 61.1%.