The Truth Shall Set You Free: Journalists' Addiction to Truth in the Face of Danger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE: THE UNITED STATES MILITARY, THE PRESS, AND THE “WOMAN WAR CORRESPONDENT,” 1846-1945 Carolyn M. Edy A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Jean Folkerts W. Fitzhugh Brundage Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Frank E. Fee, Jr. Barbara Friedman ©2012 Carolyn Martindale Edy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CAROLYN M. EDY: Conditions of Acceptance: The United States Military, the Press, and the “Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945 (Under the direction of Jean Folkerts) This dissertation chronicles the history of American women who worked as war correspondents through the end of World War II, demonstrating the ways the military, the press, and women themselves constructed categories for war reporting that promoted and prevented women’s access to war: the “war correspondent,” who covered war-related news, and the “woman war correspondent,” who covered the woman’s angle of war. As the first study to examine these concepts, from their emergence in the press through their use in military directives, this dissertation relies upon a variety of sources to consider the roles and influences, not only of the women who worked as war correspondents but of the individuals and institutions surrounding their work. Nineteenth and early 20th century newspapers continually featured the woman war correspondent—often as the first or only of her kind, even as they wrote about more than sixty such women by 1914. -

JTD EPK FINAL 8.2016.Pdf

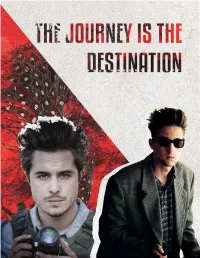

2 and O’Reilly, the journalists who be- come Dan’s guides to the world of war correspondence, Ella Purnell (Tarzan, Never Let Me Go, Maleficent), as Dan’s Synopsis sister Amy and Maria Bello (Prisoners, The Journey is the Destination is in- A History of Violence), as his mother spired by the true story of Dan Eldon, Kathy. a charismatic young activist, artist, photographer and adventurer. By As a young man of American and the age of 22, Dan had traveled to 42 British parentage growing up in Afri- countries, created a series of fine art ca, Dan Eldon always had an instinct journals that would become interna- for helping others. At the age of 19, tional best sellers, worked in refugee aware of the plight of refugees in camps, opened a business, became Malawi, he launched Student Trans- the youngest staff photojournalist at port Aid, and he and his friends Reuters, fallen in love and accumulat- drove across five African countries ed more life experience than most in a to hand-deliver the money they’d lifetime. raised to a refugee camp in the mid- dle of a war zone. Along the way Visually stunning and wildly inspiring, they witnessed examples of sublime The Journey is the Destination follows beauty and extreme hardship. The a young man’s tumultuous coming of trip changed the lives of everyone age, his exploration of love and his involved. struggle to create positive change in an increasingly violent and dangerous world. Dan was a unique person who woke up every day with the drive to make the world a little better before he went to sleep. -

“The Journey Is the Destination: Safari with Dan Eldon”

Objects of Art LA Presents a Special Exhibition “The Journey is the Destination: Safari with Dan Eldon” Limited Edition Prints from the Journals of Dan Eldon, Including Many Never Before on Offer October 6-8, 2017 September, 2017-- This October, Objects of Art LA will debut at The Reef in Los Angeles. One of the highlights is a special exhibit “The Journey is the Destination: Safari with Dan Eldon,” featuring over 25 limited edition prints from the journals of the artist, many of which were featured in the best-selling book of the same name published by Chronicle Books. Much of the work has never been on offer before and this will be the first time any of the prints will have been exhibited for sale on the West Coast. Every piece has a direct reference to Eldon’s safaris, and Objects of Art LA will be the only place to view several of his actual journals, which will also be part of the exhibition. Eldon's art is in numerous prestigious private collections, including those of Diana Rockefeller, Madonna, Julia Roberts, Christiane Amanpour and Rosie O'Donnell, among many others. There will also be two showings of the new award-winning feature film launched at the Toronto Film Festival, The Journey is the Destination, starring Maria Bello and Ben Schnetzer, which tells the story of how Dan Eldon, the artist, explorer, and Reuters photojournalist, led a group of unlikely teens on a rollicking safari across Africa to deliver aid to a refugee camp in Malawi in 1990. The film then follows Dan as he finds himself covering a famine and spiraling civil war in Somalia as Reuters’ youngest photojournalist. -

NEEDLESS DEATHS in the GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During The

NEEDLESS DEATHS IN THE GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War A Middle East Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 November 1991 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover design by Patti Lacobee Watch Committee Middle East Watch was established in 1989 to establish and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in the Middle East. The chair of Middle East Watch is Gary Sick and the vice chairs are Lisa Anderson and Bruce Rabb. Andrew Whitley is the executive director; Eric Goldstein is the research director; Virginia N. Sherry is the associate director; Aziz Abu Hamad is the senior researcher; John V. White is an Orville Schell Fellow; and Christina Derry is the associate. Needless deaths in the Gulf War: civilian casualties during the air campaign and violations of the laws of war. p. cm -- (A Middle East Watch report) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-56432-029-4 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991--United States. 2. Persian Gulf War, 1991-- Atrocities. 3. War victims--Iraq. 4. War--Protection of civilians. I. Human Rights Watch (Organization) II. Series. DS79.72.N44 1991 956.704'3--dc20 91-37902 CIP Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch is composed of Africa Watch, Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Helsinki Watch, Middle East Watch and the Fund for Free Expression. The executive committee comprises Robert L. Bernstein, chair; Adrian DeWind, vice chair; Roland Algrant, Lisa Anderson, Peter Bell, Alice Brown, William Carmichael, Dorothy Cullman, Irene Diamond, Jonathan Fanton, Jack Greenberg, Alice H. -

Media Under Fire: Reporting Conflict in Iraq

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 21 2002–03 Media Under Fire: Reporting Conflict in Iraq DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 21 2002–03 Media Under Fire: Reporting Conflict in Iraq Sarah Miskin, Politics and Public Administration Group Laura Rayner and Maria Lalic, Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments Our thanks to Jack Waterford, Jane Hearn, Cathy Madden and Alex Tewes for their useful comments and contributions on earlier drafts of this paper. -

Unquiet American: Malcolm Browne in Saigon, 1961–65

THE UNQUIET AMERICAN: Malcolm Browne in Saigon, 1961–65 The Unquiet American: Malcolm Browne in Saigon, 1961–65, other invidious means to impede reporting he perceived Browne’s photograph of the self-immolation of Thich an exhibit drawn from The Associated Press Corporate as critical of his government. Meanwhile, the White House Quan Duc, taken on June 11, 1963, led President John F. From left: Archives, honors the courageous journalism of Malcolm and Pentagon provided little information to reporters and Kennedy to reappraise U.S. support of Diem. After Diem’s Malcolm Browne at work in New York as a chemist for the Foster D. Snell Browne (1931–2012) during the early years of the Vietnam pressured them for favorable coverage of both the political murder on Nov. 1, 1963, in a coup that most probably had Co. in 1953, before his induction into the military and subsequent career War. While Browne was reporting a war being run largely and military situations. the administration’s tacit approval, Browne provided an in journalism. covertly by the White House, the CIA and the Pentagon, unmatched account of Diem’s final hours that received PHOTO COURTESY LE LIEU BROWNE he was waging his own battles in another: the war against Browne arrived in Saigon on Nov. 7, 1961, joining Vietnamese tremendous play. For his breaking news stories and his Associated Press General Manager Wes Gallagher, left, walks with AP journalists. Meanwhile, he accompanied U.S. advisers colleague Ha Van Tran. The bureau soon acquired two astute analysis of a war in the making, Browne won the correspondent Malcolm Browne in Saigon upon Gallagher’s arrival, March 20, by helicopter into the countryside seeking the latest formidable additions, correspondent Peter Arnett and Pulitzer Prize for international reporting in 1964. -

The French Strategy in Africa: France’S Role on the Continent & Its Implications for American Foreign Policy

The French Strategy in Africa: France’s Role on the Continent & its Implications for American Foreign Policy Matt Tiritilli TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin 11 May 2017 ____________________________________________________ J. Paul Pope Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs Supervising Professor ____________________________________________________ Bobby R. Inman, Admiral, U.S. Navy (ret.) Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs Second Reader Abstract In the post-World War II era, the nature of military interventions by traditional powers has changed dramatically due to changes in political priorities and the kinds of conflicts emerging in the world. Especially in the case of the French, national security interests and the decision-making process for engaging in foreign interventions has diverged significantly from the previous era and the modern American format. France has a long history of intervention on the African continent due in part to its colonial history, but also because of its modern economic and security interests there. The aim of this thesis is to articulate a framework for describing French strategy in the region and its implications for American foreign policy decisions. Contrary to the pattern of heavy-footprint, nation building interventions by the United States during this time period, the French format can instead be characterized by the rapid deployment of light forces in the attempt to successfully achieve immediate, but moderate objectives. French policy regarding Africa is based on the principles of strategic autonomy, the maintenance their status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and the ‘Europeanization’ of future initiatives. In order to achieve these objectives, France has pursued a foreign policy designed to allow flexibility and selectivity in choosing whether to intervene and to maintain the relative balance of power within their sphere of influence with itself as the regional stabilizer. -

Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq

'The Best Covered War in History': Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq by Andrew J. McLaughlin A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Andrew J. McLaughlin 2017 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Marco Rimanelli Professor, St. Leo University Supervisor(s) Andrew Hunt Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Jasmin Habib Associate Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Roger Sarty Professor, Wilfrid Laurier University Internal-external Member Brian Orend Professor, University of Waterloo ii Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This study examines combat operations from the 2003 invasion of Iraq War from the “ground up.” It utilizes unique first-person accounts that offer insights into the realities of modern warfare which include effects on soldiers, the local population, and journalists who were tasked with reporting on the action. It affirms the value of media embedding to the historian, as hundreds of journalists witnessed major combat operations firsthand. This line of argument stands in stark contrast to other academic assessments of the embedding program, which have criticized it by claiming media bias and military censorship. Here, an examination of the cultural and social dynamics of an army at war provides agency to soldiers, combat reporters, and innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. -

Famous Journalist Research Project

Famous Journalist Research Project Name:____________________________ The Assignment: You will research a famous journalist and present to the class your findings. You will introduce the journalist, describe his/her major accomplishments, why he/she is famous, how he/she got his/her start in journalism, pertinent personal information, and be able answer any questions from the journalism class. You should make yourself an "expert" on this person. You should know more about the person than you actually present. You will need to gather your information from a wide variety of sources: Internet, TV, magazines, newspapers, etc. You must include a list of all sources you consult. For modern day journalists, you MUST read/watch something they have done. (ie. If you were presenting on Barbara Walters, then you must actually watch at least one interview/story she has done, or a portion of one, if an entire story isn't available. If you choose a writer, then you must read at least ONE article written by that person.) Source Ideas: Biography.com, ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, CNN or any news websites. NO WIKIPEDIA! The Presentation: You may be as creative as you wish to be. You may use note cards or you may memorize your presentation. You must have at least ONE visual!! Any visual must include information as well as be creative. Some possibilities include dressing as the character (if they have a distinctive way of dressing) & performing in first person (imitating the journalist), creating a video, PowerPoint or make a poster of the journalist’s life, a photo album, a smore, or something else! The main idea: Be creative as well as informative. -

Hitler from American Ex-Pats' Perspective

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • MARCH 2012 Hitler From American Ex-Pats’ Perspective EVENT PREVIEW: MARCH 19 by Sonya K. Fry There have been many history books written about World War II, the economic reasons for Hitler’s rise to power, the psychology of Adolf Hitler as an art student, and a myriad of topics delving into the phenome- non that was Hitler. Andy Nagorski’s new book Hitlerland looks at this time frame from the perspective of American expatriates who lived in Andrey Rudakov Germany and witnessed the Nazi rise Andrew Nagorski to power. In researching Hitlerland, Na- Even those who did not take Hitler for the Kremlin. gorski tapped into a rich vein of in- seriously, however, would concede Others who came to Germany cu- dividual stories that provide insight that his oratory skills and charisma rious about what was going on there into what it was like to work or travel would propel him into prominence. include the architect Philip Johnson, in Germany in the midst of these Nagorski looks at Charles Lind- the dancer Josephine Baker, a young seismic events. berg who was sent to Germany in Harvard student John F. Kennedy Many of the first-hand accounts 1936 to obtain intelligence on the and historian W.E.B. Dubois. in memoirs, correspondence and in- Luftwaffe. Karl Henry von Wiegand, Andy Nagorski is an award win- terviews were from journalists and the famed Hearst correspondent was ning journalist with a long career at diplomats. There were those who the first American reporter to meet Newsweek. -

Dan Eldon: the Art of Life Jennifer New Chronicle Books, 2001

Bibliography The Art of Exploration The Journey Is the Destination Kathy Eldon EXTRAORDINARY EXPLORERS AND CREATORS INSPIRE US ALL TO REACH OUR OWN POTENTIAL Chronicle Books, 1997 Dan Eldon: The Art of Life Jennifer New Chronicle Books, 2001 Dying to Tell the Story Amy Eldon TBS The Art of Life Charles Tsai CNN Deadly Destiny: National Geographic on Assignment Patti Kim Dan Eldon National Geographic Dan Eldon was born in London in 1970 to an American Websites mother and a British father. Along with his younger sis- www.daneldon.org www.creativevisions.org ter, Amy, Dan and his family moved to Kenya in east Africa in 1977. Kenya remained Dan's home for the rest Related Books of his life, and though he traveled often - visiting more Drawing from Life: The Journal as Art than 40 countries in 22 years - he always considered Jennifer New Africa home. Princeton Architectural Press 2005 Dan's father led the east Africa division of a European computer company and his mother Kathy, an Iowa Me Against My Brother: At War in Somalia, Sudan, and Rwanda Scott Peterson native, was a freelance journalist. Kenya was a popular Routledge, 2000 destination in the late 1970s and 1980s; it was more politically stable and economically secure than most The Zanzibar Chest: A Story of Life, Love, and Death in Foreign Lands African nations, and the bountiful wildlife and perfect cli- Aidan Hartley mate made it all the more appealing. Dan and Amy grew Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003 up with a constant stream of interesting visitors at their dinner table. -

6. from Vietnam to Iraq: Negative Trends in Television War Reporting

THE PUBLIC RIGHT TO KNOW 6. From Vietnam to Iraq: Negative trends in television war reporting ABSTRACT In 1876, an American newspaperman with the US 7th Cavalry, Mark Kellogg, declared: ‘I go with Custer, and will be at the death.’1 This overtly heroic pronouncement embodies what many still want to believe is the greatest role in journalism: to go up to the fight, to be with ‘the boys’, to expose yourself to risk, to get the story and the blood-soaked images, to vividly describe a world of strength and weakness, of courage under fire, of victory and defeat—and, quite possibly, to die. So culturally embedded has this idea become that it raises hopes among thousands of journalism students worldwide that they too might become that holiest of entities in the media pantheon, the television war correspondent. They may find they have left it too late. Accompanied by evolutionary technologies and breathtaking media change, TV war reporting has shifted from an independent style of filmed reportage to live pieces-to-camera from reporters who have little or nothing to say. In this article, I explore how this has come about; offer some views about the resulting negative impact on practitioners and the public; and explain why, in my opinion, our ‘right to know’ about warfare has been seriously eroded as a result. Keywords: conflict reporting, embedded, television war reporting, war correspondents TONY MANIATY Australian Centre for Independent Journalism N 22nd December 1961, the first American serviceman was killed in Saigon. By April 1969 a staggering 543,000 US troops occupied OSouth Vietnam, with calls from field commanders for even more.