The Museum As Agent of Participatory Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX R.10 List of Recipients for Draft EIS

APPENDIX R.10 List of Recipients for Draft EIS LGA Access Improvement Project EIS August 2020 List of Recipients for Draft EIS Stakeholder category Affiliation Full Name District 19 Paul Vallone District 20 Peter Koo Local Officials District 21 Francisco Moya District 22 Costa Constantinides District 25 Daniel Dromm New York State Andrew M. Cuomo United States Senate Chuck E. Schumer United States Senate Kirsten Gillibrand New York City Bill de Blasio State Senate District 11 John C. Liu State Senate District 12 Michael Gianaris State Senate District 13 Jessica Ramos State Senate District 13 Maria Barlis State Senate District 16 Toby Ann Stavisky State Senate District 34 Alessandra Biaggi State Elected Officials New York State Assembly District 27 Daniel Rosenthal New York State Assembly District 34 Michael G. DenDekker New York State Assembly District 35 Jeffrion L. Aubry New York State Assembly District 35 Lily Pioche New York State Assembly District 36 Aravella Simotas New York State Assembly District 39 Catalina Cruz Borough of Queens Melinda Katz NY's 8th Congressional District (Brooklyn and Queens) in the US House Hakeem Jeffries New York District 14 Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez New York 35th Assembly District Hiram Montserrate NYS Laborers Vinny Albanese NYS Laborers Steven D' Amato Global Business Travel Association Patrick Algyer Queens Community Board 7 Charles Apelian Hudson Yards Hells Kitchen Alliance Robert Benfatto Bryant Park Corporation Dan Biederman Bryant Park Corporation - Citi Field Dan Biederman Garment District Alliance -

E-Participation: a Quick Overview of Recent Qualitative Trends

DESA Working Paper No. 163 ST/ESA/2020/DWP/163 JANUARY 2020 E-participation: a quick overview of recent qualitative trends Author: David Le Blanc ABSTRACT This paper briefly takes stock of two decades of e-participation initiatives based on a limited review of the academic literature. The purpose of the paper is to complement the results of the e-government Survey 2020. As such, the emphasis is on aspects that the e-government survey (based on analysis of e-government portals and on quantitative indicators) does not capture directly. Among those are the challenges faced by e-participation initiatives and key areas of attention for governments. The paper maps the field of e-par- ticipation and related activities, as well as its relationships with other governance concepts. Areas of recent development in terms of e-participation applications are briefly reviewed. The paper selectively highlights conclusions from the literature on different participation tools, as well as a list of key problematic areas for policy makers. The paper concludes that while e-participation platforms using new technologies have spread rapidly in developed countries in the first decade of the 2000s and in developing countries during the last 10 years, it is not clear that their multiplication has translated into broader or deeper citizen participation. Be- yond reasons related to technology access and digital skills, factors such as lack of understanding of citizens’ motivations to participate and the reluctance of public institutions to genuinely share agenda setting and decision-making power seem to play an important role in the observed limited progress. -

Deep Disparities TODAY December 20, 2019

Volume 65, No. 174 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 20, 2019 50¢ QUEENS Deep disparities TODAY December 20, 2019 A MAN WAS SHOT AND KILLED outside a Rockaway Beach Key Food supermarket on Wednesday, Patch.com reports. The incident took place shortly after 6 p.m. at 87-15 Rockaway Beach Blvd., police said. The 45-year-old victim was shot multiple times in the arms and chest. Borough President Melinda Katz presided over the swearing-in ceremony of 345 Queens community board appointees earlier this FIFTEEN OF QUEENS’ 16 COUNCIL- year. Photo via the Borough President’s Office members voted in favor of a measure that By David Brand board, and men outnumber women by a wide would force affordable housing developers Significant racial, Queens Daily Eagle margin on several boards. In contrast, Latinx who receive city funding to set aside 15 Queens has earned a reputation as the residents are underrepresented — sometimes percent of the units for homeless New most diverse county in the United States, but by a huge margin — on all but one commu- Yorkers. Councilmember I. Daneek Miller age and gender the borough’s 14 local community boards — nity board, while Asian people are underrep- abstained from voting and cited concerns key conduits between communities and city resented on all but four boards. Meanwhile, about a saturation of affordable housing disparities affect government — rarely reflect the demograph- women make up less than 40 percent of developments in his district. ics of the districts they represent, according members on half of the boards and only six every community to an analysis by the Eagle and Measure of community board members — of 663 total — America. -

Towards a Revised Framework for Participatory Planning in the Context of Risk

sustainability Article Towards a Revised Framework for Participatory Planning in the Context of Risk Paola Rizzi 1,* and Anna Por˛ebska 2 1 Department of Architecture, Design and Urban Planning, University of Sassari, 07100 Sassari, Italy 2 Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology, 31-155 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 April 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 9 July 2020 Abstract: Community participation is widely acknowledged to be crucial in both mitigation and reconstruction planning, as well as in community-based disaster risk reduction (CBDRR) and community-based disaster mitigation (CBDM) processes. However, despite decades of experience, an efficient framework that is acceptable for all actors and suitable for all different phases of the process—ranging from planning to post-disaster recovery—is lacking. The examples presented in this paper shed light on the different dynamics of participatory design processes and compare situations in which participatory design and community planning were introduced before, during, or after a disastrous or potentially disastrous event. Others emphasize the consequences of participation not being introduced at all. Analysis of these processes allows the authors to speculate on a revised, universal model for participatory planning in vulnerable territories and in the context of risk. By emphasizing intrinsic relations of different elements of the process, particularly the responsibility that different actors are prepared—or forced—to take, this article offers insight towards a framework for post-2020 participatory planning. Keywords: participatory design; design for risk reduction (DRR); disaster mitigation (DM); risk awareness; resilience 1. Introduction 1.1. -

Fiscal Year 2017 Statement of Community District Needs and Community Board Budget Requests

Fiscal Year 2017 Statement of Community District Needs and Community Board Budget Requests for Queens Community Board 3 Submitted to the Department of City Planning December 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1. Community Board Information 2. Overview of Community District 3. Main Issues 4. Summary of Community District Needs and Community Board Budget Requests 4.1. Health Care and Human Service Needs and Requests 4.1.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Health Care Facilities and Programming 4.1.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Facilities and Programming for Older New Yorkers 4.1.3 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Facilities and Services for the Homeless 4.1.4 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Services and Programming for Low-Income and Vulnerable New Yorkers 4.2. Youth, Education and Child Welfare Needs and Requests 4.2.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Educational Facilities and Programs 4.2.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Services for Children and Child Welfare 4.2.3 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Youth and Community Services and Programs 4.3. Public Safety Needs and Requests 4.3.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Policing and Crime 4.3.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Emergency Services 4.4. Core Infrastructure and City Services Needs and Requests 4.4.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Water, Sewers and Environmental Protection 4.4.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Sanitation Services 4.5. Land Use, Housing and Economic Development Needs and Requests 4.5.1 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Land Use 4.5.2 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Housing Needs and Programming 4.5.3 Community District Needs and Requests Related to Economic Development 4.6. -

Guardians of Flushing Bay's

October 20, 2020 Mr. Andrew Brooks Environmental Program Manager - Airports Division Federal Aviation Administration Eastern Regional Office, AEA-610 1 Aviation Plaza Jamaica, New York 11434 Sent via email [email protected] Dear Mr. Brooks: On behalf of the Guardians of Flushing Bay, thank you for the opportunity to comment on the proposed LaGuardia Airport Access Improvement Project’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS). Guardians of Flushing Bay (GoFB) is a coalition of residents, human-powered boaters and park users advocating for a healthy and equitably accessible Flushing Bay and Creek. Through waterfront programming, hands on stewardship, community visioning and bottom up advocacy GoFB strives to realize Flushing Waterways as a place where our most marginalized watershed residents can learn, work and thrive.We are also a member of the Sensible Way to LGA coalition, a united group of local residents, community-based organizations, and citywide partners fighting for a substantial and meaningful LGA Airtrain EIS process that produces the best alternative for all New Yorkers. And we are long standing partners of Riverkeeper, an environmental watchdog group protecting and restoring the Hudson River and its tributaries (of which Flushing Bay and Creek are included). Project Background The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (Port Authority) proposes to construct an elevated AirTrain to carry passengers between The New York City Transit Authority Mets-Willets Point and the LaGuardia Airport. The proposal comprises multiple pieces of large scale infrastructure. For operations and support infrastructure, the proposal calls for a passenger and walkway systems, parking garages, ground transportation facilities, a multilevel operations, maintenance, and storage facility with 500 Airport employee parking spaces, traction power substations located at the on-airport East Station, the Mets-Willets Point Station, a 27kV main substation, and utilities infrastructure. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Participatory Planning in Education. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris (France). OECD

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 107 653 SP 009 280 TITLE Participatory Planning in Education. INSTITUTION Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris (France). PUB DATE 74 NOTE 369p. AVAILABLE FROMOECD Publications Center, Suite 1207, 1750 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.V., Washington, D.C. 20006 ($13.50) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$18.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Educational Coordination; Educational Needs; *Educational Planning; *Educational Policy; *Educational Strategies; Foreign Countries; Participation; School Planning ABSTRACT This three-part book is part ofa series exploring educational policy planning, published by theOrganization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)Education Committee. The articles in this collectivn resulting froma January 1973 conference, focus on pedagogical and organizationaldimensions. The first part of the book presentsa review of the conference discussions, as well as its agenda andan orientation paper on participatory planning. Part two consists ofpapers which report experiments in participation and planning from thefield, with examples ranging from specific institutions to thenational level. The papers in part three, also basedon fieldwork, emphasize conceptual developments which suggest how planning mightbe seen as a participatory process. (Author/PB) PARTICIPATORY PLANNING IN EDUCATION HEALTH. US DEPROITMENT OP IIIMPCATION I WILPARS PERMISSION TU REPRODUCE THIS COPY- NE1714AL 'willow*, RIGHTED MATERIAL AS SEEN GRANTED BY EDUCATION SEEN REPRO THIS DOCUMENT HASRECEIVEO FR Duce° EXACTLY AS ORIGINGIN -

2015 City Council District Profiles

B RO O K LY N CITY COUNCIL MIDTOWN LONG SOUTH ISLAND CITY DISTRICT MURRAY 2015 CityHILL Council District Profiles W 28 ST SUNNYSIDE GARDENS CHELSEA E 33 ST HUNTERS QUEENS BLVD 33 POINT 49 AVE HUNTE T FLATIRON BO R S RDE S S L P N A L O T VE I IN S 3 K T E H A TC VE W M DU W 14 ST C G U BLISSVILLE I 46 ST N N PROVOST ST E GRAMERCY S S K IN 4 B N ST G FREEMA L S V L A VE D N A UNION GREEN ST N 5 D STUYVESANT E SQUARE HURON ST A W TOWN V INDIA ST E T O 26 W T AVE N EENPOIN WESTGreenpoint GR CR 19 EEK MASPETH GREENPOINT North Side AVE OAK ST NORMAN VE South Side AVE NEWEL ST A LE ECKFORD ST EAST RO SE MANHATTAN AVE AVE BUSHWIC ME NASSAU Williamsburg VILLAGE K INLET MEEKER R HOUSTON ST Clinton HillU SOHO 4 30 S E T C V A S E AVE T VE H DRIGGS Vinegar Hill A 6 T GREENWICH ST Y W Brooklyn Heights HUDSON RIVER 5 LITTLE ITALY 2 NORTH VE A Downtown Brooklyn SIDE 28 2 N 10 ST ORD VE BoerumD A Hill 1 BOWERY DF GRAN BE N 8 ST CHAMBERS ST CHINATOWN R N 3 ST D N 6 ST R D CIVIC F AN AVE BATTERY ETROPOLIT CENTER LOWER S 1 ST M PARK EAST SIDE EAST SOUTH CITY S 3 ST WILLIAMSBURG SIDE WILLIAMSBURG B L U E S H N W N A I FLUSHING AVE C H K C EAST RIVER NAVY A V T E YARD U O W B 16 A BASIN L Y L 23 C A 34 KO W HOOPER ST JOHN ST PENN ST FF A 1 27 LEE AVE VE WATER ST HEYWARD ST MIDDLETON ST 21 14 10 33 26 BUSHWICK 37 30 20 Navy Yard FRANKLIN 9 NOSTRAND 3 8 AVE BROADWAY BUSHWICK 11 FLUSHING AVE PARK 13 HICKS ST 25 HENRY ST BROOKLYN QUEENS EXPWY BEDFORD TLE AVE 15 A MYR BROOKLYN 24 VE 17 A HEIGHTS VE Legend JORALEMON ST A VE FULTON ST AVE GROVE ST 7 WILLOUGHBY ATLANTIC -

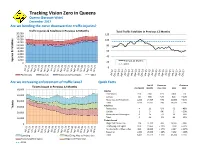

Tracking Vision Zero in Queens

Tracking Vision Zero in Queens Queens (Borough-Wide) December 2017 Are we bending the curve downward on traffic injuries? Traffic Injuries & Fatalities in Previous 12 Months Total Traffic Fatalities in Previous 12 Months 20,000 120 18,000 16,000 100 14,000 12,000 80 10,000 8,000 60 6,000 4,000 40 2,000 Injuries Injuries &Fatalities 20 Previous 12 Months 0 2013 0 Pedestrians Cyclists Motorists & Passengers 2013 Are we increasing enforcement of traffic laws? Quick Facts Past 12 Change vs. Change vs. Tickets Issued in Previous 12 Months This Month Months Prev. Year 2013 2013 60,000 Injuries Pedestrians 270 2,641 + 1% 2,801 - 6% 50,000 Cyclists 50 906 + 2% 826 + 10% 40,000 Motorists and Passengers 1,216 14,424 + 0% 11,895 + 21% Total 1,536 17,971 + 0% 15,522 + 16% 30,000 Fatalities Tickets Pedestrians 4 31 - 3% 52 - 40% 20,000 Cyclists 1 3 0% 2 + 50% Motorists and Passengers 0 26 - 7% 39 - 33% 10,000 Total 5 60 - 5% 93 - 35% Tickets Issued 0 Illegal Cell Phone Use 736 14,120 - 6% 26,967 - 48% Disobeying Red Signal 870 11,963 + 11% 7,538 + 59% Not Giving Rt of Way to Ped 811 10,824 + 27% 3,647 + 197% Speeding 1,065 15,606 + 28% 7,132 + 119% Speeding Not Giving Way to Pedestrians Total 3,482 52,513 + 13% 45,284 + 16% Disobeying Red Signal Illegal Cell Phone Use 2013 Tracking Vision Zero Bronx December 2017 Are we bending the curve downward on traffic injuries? Traffic Injuries & Fatalities in Previous 12 Months Total Traffic Fatalities in Previous 12 Months 12,000 70 10,000 60 8,000 50 6,000 40 4,000 30 20 2,000 Previous 12 Months Injuries Injuries &Fatalities 0 10 2013 0 Pedestrians Cyclists Motorists & Passengers 2013 Are we increasing enforcement of traffic laws? Quick Facts Past 12 Change vs. -

U R B a N LIFE And

URBAN LIFE and URBAN LANDSCAPE SERIES CINCINNATI'S OVER-THE-RHINE AND TWENTIETH-CENTURY URBANISM Zane L. Miller and Bruce Tucker OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Columbus Copyright © 1998 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Miller, Zane L. Changing plans for America's inner cities : Cincinnati's Over-The-Rhine and twentieth-century urbanism / Zane L. Miller and Bruce Tucker. p. cm. — (Urban life and urban landscape series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-0762-6 (cloth : alk. paper).—ISBN 0-8142-0763-4 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Urban renewal—Ohio—Cincinnati—History. 2. Over-the-Rhine (Cincinnati, Ohio)—History. I. Tucker, Bruce, 1948 . 11. Title. III. Series. HT177.C53M55 1997 307.3'416'0977178—dc21 97-26206 CIP Text and jacket design by Gary Gore. Type set in ITC New Baskerville by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services. Printed by Thomson-Shore. The paper in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 98765432 1 For Henry List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: Why Cincinnati, Why Over-the-Rhine? xv Prologue: 1850s-1910s 1 PART ONE ZONING, RAZING, OR REHABILITATION Introduction: From Cultural Engineering to Cultural Individualism 9 1 Social Groups, Slums, and Comprehensive Planning, 1915-1944 13 2 Neighborhoods and a Community, 1948-1960 29 PART TWO NEW VISIONS AND VISIONARIES Introduction: Community Action and -

History & Theory of Planning

History and Theory of Planning Why do we do what we do? What is planning? a universal human activity involving the consideration of outcomes before choosing amongst alternatives a deliberate, self-conscious activity School of City and Regional Planning, Georgia Tech Primary functions of planning improve efficiency of outcomes optimize counterbalance market failures balance public and private interests widen the range of choice enhance consciousness of decision making civic engagement expand opportunity and understanding in community School of City and Regional Planning, Georgia Tech What is the role of history and theory in understanding planning? planning is rooted in applied disciplines primary interest in practical problem solving early planning theories emerged out of practice planning codified as a professional activity originally transmitted by practitioners via apprenticeships efforts to develop a coherent theory emerged in the 1950s and 60s need to rationalize the interests and activities of planning under conditions of social foment the social sciences as a more broadly based interpretive lens School of City and Regional Planning, Georgia Tech Types of theories theories of system operations How do cities, regions, communities, etc. work? • disciplinary knowledge such as economics and environmental science theories of system change How might planners act? • disciplinary knowledge such as decision theory, political science, and negotiation theory • applied disciplines such as public administration and engineering School of City -

HOSPECO Key Player in New NYC Law Guaranteeing FREE Femhy Products Company Supports Women’S Initiative with Free Product Dispenser

HOSPECO Key Player in New NYC Law Guaranteeing FREE FemHy Products Company supports women’s initiative with free product dispenser CLEVELAND—July 14, 2016—HOSPECO® , a pioneer and leader in the feminine hygiene dispensing category and a leading manufacturer of cleaning and protection products serving the “away from home” marketplace, is pleased to have played an integral part in new legislation signed today in New York City. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio today signed a package of legislation guaranteeing access to free feminine hygiene products to a wide-ranging group of women and girls who are generally unable to easily afford or obtain these products. The group includes Department of Correction inmates, persons residing in a city shelter, youth under the care of certain children’s services facilities, and public school students. The signing of this legislation comes as a result of continued efforts by officials including New York City Councilwoman Julissa Ferreras-Copeland as part of an initiative to make free feminine hygiene products more widely available across the city. “I am proud to lead the nation towards menstrual equity by guaranteeing access to pads and tampons to hundreds of thousands of women and girls,” said Ferreras-Copeland. “These laws recognize that feminine hygiene products are a necessity—not a luxury,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio. “I am proud to sign these bills into law.” In June, New York City Council unanimously voted to pass this legislation, which will affect, among other institutions, 800 public schools, requiring them to install the free feminine hygiene dispensers in all girls’ bathrooms.