Page 1 Sanchez 1 C O N J U R I N G the M O D E R N W O M a N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old and the New Magic

E^2 CORNELL UNIVERSITY gilBRARY . GIFT OF THE AUTHOR Digitized by Microsoft® T^^irt m4:£±z^ mM^^ 315J2A. j^^/; ii'./jvf:( -UPHF ^§?i=£=^ PB1NTEDINU.S.A. Library Cornell University GV1547 .E92 Old and the new maj 743 3 1924 029 935 olin Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® ROBERT-KCUIUT Digitized by Microsoft® THE OLDUI^DIMEJ^ MAGIC BY HENRY RIDGELY EVANS INTRODUCTION E1^ k -io^s-ji, Copyright 1906 BY The Open Court Publishing Co. Chicago -J' Digitized by Microsoft® \\\ ' SKETCH OF HENRY RIDGELY EVAXS. "Elenry Ridgely Evans, journalist, author and librarian, was born in Baltimore, ^Md., Xovember 7, 1861. He is the son 01 Henry Cotheal and Alary (Garrettson) Evans. Through his mother he is descended from the old colonial families of Ridgely, Dorsey, AA'orthington and Greenberry, which played such a prominent part in the annals of early Maryland. \h. Evans was educated at the preparatory department of Georgetown ( D. C.) College and at Columbian College, Washington, D. C He studied law at the University of Maryland, and began its practice in Baltimore City ; but abandoned the legal profession for the more congenial a\'ocation <jf journalism. He served for a number of }ears as special reporter and dramatic critic on the 'Baltimore N'ews,' and subsequently became connected with the U. -

Biography Events&Services

MAGICIAN ILLUSIONIST ENTERTAINER RSJ Press Kit - Award-Winning Magic & Entertainment BIOGRAPHY For the past 20 years, Rick has been amazing audiences with trademark card throwing, close up magic, sleight of hand, and stage shows with unbelievable feats of mentalism. Grand Illusions include appearances, disappearances, levitations, cutting his assistants in half, and Harry Houdini’s famous metamorphosis. Rick has had guest appearances on national television including “ABC’s Shark Tank”, “America’s Got Talent”, “The Ellen DeGeneres Show”, “Last Call with Carson Daly”, “Steve Harvey’s Big Time”, “The Wayne Brady Show”, “Ripley’s Believe it or Not!”, “Master of Champions”, “Time Warp”, “The Tonight Show” with Jay Leno, and many more. EVENTS&SERVICES Offering jaw-dropping magic & illusion for events globally, Rick Smith Jr. has the ability to entertain any audience in any environment. • Corporate Banquets • Stage and Illusion Shows • Tradeshows • Strolling Entertainment • Private Events • Card-Throwing Appearances • Colleges & Universities • Brand Promotion & Marketing • Emcee Services CLIENTS INCLUDE: www.RickSmithJr.com 3 Time Guinness World-Record Holder for Throwing a Playing Card the Farthest, Highest & Most Accurate RSJ Press Kit - Award-Winning Magic & Entertainment STUNNINGILLUSIONS From New York to Las Vegas, Rick is equipped with the abiilty to present cutting edge magic and grand illusion for your next event. EVENTS&SERVICES Rick and his team can handle full event production for your company or private event. Enhance the production value of the show with video, lighting and professional sound. • Lighting Packages • Green Screen Photography • Uplighting and Gobos • Special Effects & Decoration • DJ and Event Music • Professional Photography • IMAG and Live Video • Special Guest Entertainers AS SEEN ON: AND DOZENS MORE.. -

Attention and Awareness in Stage Magic: Turning Tricks Into Research

PERSPECTIVES involve higher-level cognitive functions, SCIENCE AND SOCIETY such as attention and causal inference (most coin and card tricks used by magicians fall Attention and awareness in stage into this category). The application of all these devices by magic: turning tricks into research the expert magician gives the impression of a ‘magical’ event that is impossible in the physical realm (see TABLE 1 for a classifica- Stephen L. Macknik, Mac King, James Randi, Apollo Robbins, Teller, tion of the main types of magic effects and John Thompson and Susana Martinez-Conde their underlying methods). This Perspective addresses how cognitive and visual illusions Abstract | Just as vision scientists study visual art and illusions to elucidate the are applied in magic, and their underlying workings of the visual system, so too can cognitive scientists study cognitive neural mechanisms. We also discuss some of illusions to elucidate the underpinnings of cognition. Magic shows are a the principles that have been developed by manifestation of accomplished magic performers’ deep intuition for and magicians and pickpockets throughout the understanding of human attention and awareness. By studying magicians and their centuries to manipulate awareness and atten- tion, as well as their potential applications techniques, neuroscientists can learn powerful methods to manipulate attention to research, especially in the study of the and awareness in the laboratory. Such methods could be exploited to directly study brain mechanisms that underlie attention the behavioural and neural basis of consciousness itself, for instance through the and awareness. This Perspective therefore use of brain imaging and other neural recording techniques. seeks to inform the cognitive neuroscientist that the techniques used by magicians can be powerful and robust tools to take to the Magic is one of the oldest and most wide- powers. -

Proquest Dissertations

Early Cinema and the Supernatural by Murray Leeder B.A. (Honours) English, University of Calgary, M.A. Film Studies, Carleton University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations © Murray Leeder September 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83208-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83208-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Perspectives

Nature Reviews Neuroscience | AOP, published online 30 July 2008; doi:10.1038/nrn2473 PERSPECTIVES involve higher-level cognitive functions, SCIENCE AND SOCIETY such as attention and causal inference (most coin and card tricks used by magicians fall Attention and awareness in stage into this category). The application of all these devices by magic: turning tricks into research the expert magician gives the impression of a ‘magical’ event that is impossible in the physical realm (see TABLE 1 for a classifica- Stephen L. Macknik, Mac King, James Randi, Apollo Robbins, Teller, tion of the main types of magic effects and John Thompson and Susana Martinez-Conde their underlying methods). This Perspective addresses how cognitive and visual illusions Abstract | Just as vision scientists study visual art and illusions to elucidate the are applied in magic, and their underlying workings of the visual system, so too can cognitive scientists study cognitive neural mechanisms. We also discuss some of illusions to elucidate the underpinnings of cognition. Magic shows are a the principles that have been developed by manifestation of accomplished magic performers’ deep intuition for and magicians and pickpockets throughout the understanding of human attention and awareness. By studying magicians and their centuries to manipulate awareness and atten- tion, as well as their potential applications techniques, neuroscientists can learn powerful methods to manipulate attention to research, especially in the study of the and awareness in the laboratory. Such methods could be exploited to directly study brain mechanisms that underlie attention the behavioural and neural basis of consciousness itself, for instance through the and awareness. -

Abbott Downloads Over 1100 Downloads

2013 ABBOTT DOWNLOADS OVER 1100 DOWNLOADS Thank you for taking the time to download this catalog. We have organized the downloads as they are on the website – Access Point Worldwide, Books, Manuscripts, Workshop Plans, Tops Magazines, Free With Purchase. Clicking on a link will take you directly to that category. Greg Bordner Abbott Magic Company 5/3/2013 Contents ACCESS POINT WORLDWIDE ............................................................................................................ 4 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE BOOKS ............................................................................................... 19 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE MANUSCRIPTS ................................................................................ 23 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE WORKSHOP PLANS ....................................................................... 26 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE TOPS MAGAZINES ......................................................................... 30 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE INSTRUCTIONS .............................................................................. 32 ABBOTT FREE DOWNLOADS ........................................................................................................... 50 ACCESS POINT WORLDWIDE The latest downloads from around the world – Downloads range in price 100 percent Commercial Volume 1 - Comedy Stand Up 100 percent Commercial Volume 2 - Mentalism 100 percent Commercial Volume 3 - Closeup Magic 21 by Shin Lim, Donald Carlson & Jose Morales video 24Seven Vol. 1 by John Carey and RSVP Magic video 24Seven Vol. -

David Copperfield PAGE 36

JUNE 2012 DAVID COPPERFIELD PAGE 36 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Mona S. Morrison, M-U-M Advertising Manager 645 Darien Court, Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: (847) 519-9201 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Fax: 866-591-7392 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - JUNE 2012 M-U-M JUNE 2012 MAGAZINE Volume 102 • Number 1 S.A.M. NEWS 6 From the Editor’s Desk Photo by Herb Ritts 8 From the President’s Desk 11 M-U-M Assembly News 24 New Members 25 -

Programmes of Magicians

LATEST MAGICAL BOOKS. AL BAKER'S PROUDLOCK'S TWO BOOKS. EGG BAG & FOUR You all know Al ACE Presentation. Baker's kind of ECC BAG Maqic. Real smart Thit book is well pro- ic that appeals FOUR all. Tricks YOU will work. • Well Illustrated. V Vol. One 5/6. Vol. Two 4/-. Postage 3d. ODERN MASTER MYSTERIES. »w tricks for tha irlour, Club or ^age. 108 pages, "'.'th many illuitra- jf'pns. Very few eft. Buy now I ' ice 5/6. Post 3d. /ENTRILOQUISM. By M. Hurling, small practical WILL ALMA Spok. If you want M.I.M.C. (LONDON) , > become a ven- : jloquist you cannot ake a better sta[t 1 uu I i man with this book. detail. New Gags, New Dialogues. Price 5/6. Post 3d. Price 2/6. Post 3d. SEALED MESSAGE READING THE ODIN KINGS METHODS. The last word on the A full and exhaus- Chinese Rings. An tive treatise on all entirely new method of presentation invented the different by Claudius Odin. mehtods used by Translated and Edited the leading Acts of by Victor Farelli 6/6 to-day. Price Price 8/-. Post 3d. Printed and Published by L. D. & Co., London. Copyright PROGRAMMES OF MAGICIANS (REVISED, WHERE POSSIBLE, BY THE PERFORMERS THEMSELVES) Showing at a glance the tricks performed by all the leading conjurors, extending over a period of forty-two years, from 1864 to 1906 An Invaluable Guide for the Amateur and Professional Just the Book that every Magician wants COMPILED, WITH NOTES, BY J. F. BURROWS {Author of The Lightning Artist, Some New Magic, etc., etc. -

Harry Houdini and Howard Thurston Were So Popular That the Era Became Known As the Golden Age of Magic

Illusions The Art of Magic Large Print Exhibition Text This exhibition is organized by the McCord Museum in Montreal. All of the framed posters on view are from the McCord’s Allan Slaight Collection. Lead La Fondation Emmanuelle Gattuso Supporters The Slaight Foundation Exhibition Overview There are 9 sections in this exhibition, including a retail shop. Visitors will enter Section 1, upon turning right, after passing through the entrance. Enter / Exit Section 1 Content: Exhibition title wall with 1 photograph and partnership recognition, and 2 posters on the wall. Environment: shared thoroughfare with exhibition exit. Section 2 Content: 9 posters on the wall, 1 projected film with ambient audio, and 1 table case containing 4 objects Environment: darkened gallery setting with no seating. Section 3 Content: 9 posters on the wall. Environment: standard gallery setting with no seating. Section 4 Content: 9 posters on the wall. Environment: standard gallery setting with bench seating. Section 5 Content: 8 posters on the wall, 1 short film with ambient audio, 1 table case containing 9 objects, and an interactive activity station with seating. Environment: standard gallery setting with no seating. Section 6 Content: 7 posters on the wall. Environment: standard gallery setting with no seating. Section 7 Content: 6 posters on the wall. Environment: standard gallery setting with no seating. Section 8 Content: 7 posters on the wall, 2 projected silent films, 1 table case containing 15 objects, and a free-standing object. Environment: standard gallery setting with dim lighting. No available seating. Section 9 (Retail Shop) Visitors must enter through the retail shop to exit the exhibition. -

Exhibition Guide & Event Highlights Staging Magic

EXHIBITION GUIDE & EVENT HIGHLIGHTS STAGING MAGIC A warm welcome to Senate House Library and to Staging Magic: The Story Behind the Illusion, an adventure through the history of conjuring and magic as entertainment, a centuries-long fascination that still excites and inspires today. The exhibition displays items on the history of magic from Senate House Library’s collection. The library houses and cares for more than 2 million books, 50 named special collections and over 1,800 archives. It’s one of the UK’s largest academic libraries focused on the arts, humanities and social sciences and holds a wealth of primary source material from the medieval period to the modern age. I hope that you are inspired by the exhibition and accompanying events, as we explore magic’s spell on society from illustrious performances in the top theatres, and street and parlour tricks that have sparked the imagination of society. Dr Nick Barratt Director, Senate House Library INTRODUCTION The exhibition features over 60 stories which focus on magic in the form of sleight-of-hand (legerdemain) and stage illusions, from 16th century court jugglers to the great masters of the golden age of magic in the 19th and early 20th centuries. These stories are told through the books, manuscripts and ephemera of the Harry Price Library of Magical Literature. Through five interconnected themes, the exhibition explores how magic has remained a mainstay of popular culture in the western world, how its secrets have been kept and revealed, and how magicians have innovated to continue to surprise and enchant their audiences. -

Second Sight” Illusion, Media, and Mediums Katharina Rein Bauhaus Universitat Weimar, [email protected]

communication +1 Volume 4 Issue 1 Occult Communications: On Article 8 Instrumentation, Esotericism, and Epistemology September 2015 Mind Reading in Stage Magic: The “Second Sight” Illusion, Media, and Mediums Katharina Rein Bauhaus Universitat Weimar, [email protected] Abstract This article analyzes the late-nineteenth-century stage illusion “The Second Sight,” which seemingly demonstrates the performers’ telepathic abilities. The illusion is on the one hand regarded as an expression of contemporary trends in cultural imagination as it seizes upon notions implied by spiritualism as well as utopian and dystopian ideas associated with technical media. On the other hand, the spread of binary code in communication can be traced along with the development of the "Second Sight," the latter being outlined by means of three examples using different methods to obtain a similar effect. While the first version used a speaking code to transmit information, the other two were performed silently, relying on other ways of communication. The article reveals how stage magic, technical media, spiritualism, and mind reading were interconnected in the late nineteenth century, and drove each other forward. Keywords stage magic, media, spiritualism, telepathy, telegraphy, telephony This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Rein / The “Second Sight” Illusion, Media, and Mediums Despite stage magic’s continuous presence in popular culture and its historical significance as a form of entertainment, it has received relatively little academic attention. This article deals with a late-nineteenth-century stage illusion called “The Second Sight” which seemingly demonstrates the performers’ ability to read each other’s minds. -

Donothave.Pdf

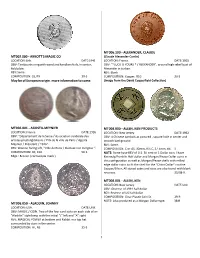

MT006.100 - ALEXANDER, CLAUDE MT002.000 - ABBOTT'S MAGIC CO (Claude Alexander Conlin) LOCATION: Unk. DATE:1946 LOCATION: France. DATE:1915 OBV: Tambourine ring with wand and handkerchiefs, in center, OBV: "*LUCK IS YOURS * / ALEXANDER", around high relief bust of field plain. Alexander in turban. REV: Same. REV: Blank. COMPOSITION: GS, R9. 39-S COMPOSITION: Copper, R10. 20-S May be of European origin. more information to come. (Image from the David Copperfield Collection) MT006.001 - AGOSTA-MEYNIER MT008.000 - ALLEN, KEN PRODUCTS LOCATION: France. DATE:1926 LOCATION: New Jersey. DATE:1962 OBV: "Département de la Seine / Association syndicale des OBV: 4 Chinese symbols as pictured , square hole in center and artistes prestidigitateurs / Prix de la ville de Paris / Agosta smooth background. Meynier / Président / 1926". REV: Same. REV: Woman facing left, "Ville de Paris / Fluctuat nec mergitur ". COMPOSITION: C or GS, 30mm, R3; C, 37.5mm, R4. S COMPOSITION: BZ, R10. 50-S NOTE: Some have REV of U.S. 50 cent or 1 Dollar coin. I have Edge : Bronze ( cornucopia mark ) Kennedy/Franklin Half dollar and Morgan/Peace Dollar coins in this configuration as well as Morgan/Peace shells with milled edge dollar coins to fit the shell for the “China Dollar” routine Copper/Silver, All stated coins and sizes are also found with blank reverses. 35/38-R. MT008.001 - ALLEN, KEN LOCATION: New Jersey. DATE:Unk OBV: Obverse of 1944 half dollar REV: Reverse of US half dollar COMPOSITION: Clear Plastic Coin St. 29-R NOTE: Also produced as a Morgan Dollar type. 38-R MT006.050 - ALADDIN, JOHNNY LOCATION: USA.