Hocus Pocus: the Magic Within Trade Secret Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Street Magic Revealed

Black Diamond Ultimate Street Magic Revealed Thank you for your purchase from Please feel free to … Take a look at our ebay auctions: ebay ID: www-netgeneration-co-uk Visit our website – www.netgeneration.co.uk Or send us an email - [email protected] 2 IMPROMPTU CARD FIND EFFECT A card is selected by a spectator and placed back on top of the pack. The pack is then cut several times and handed back to the magician. A pile of cards suddenly falls off the pack, leaving the magician holding the spectators card. METHOD When the card is selected by the spectator, the card on the bottom of the pack is crimped by the magician’s pinky. The spectator’s card is then placed on the top of the pack and the pack is cut. This now means that the spectator’s card is underneath the crimped card. The pack can be passed around the room to be cut several times and the spectator’s card will always be under the crimped card. The pack is then handed back to the magician who quietly puts his thumb under the crimped card appearing to be clumsy and allows the cards above his thumb to fall on the floor. The card under his thumb will be the spectators. The magician can also allow the rest of the cards to fall, leaving only the spectators card in his hand. This trick looks amazing because the audience has seen that the magician has not had a lot of contact with the pack and the whole routine has been totally impromptu. -

Eugene Burger (1939-2017)

1 Eugene Burger (1939-2017) Photo: Michael Caplan A Celebration of Life and Legacy by Lawrence Hass, Ph.D. August 19, 2017 (This obituary was written at the request of Eugene Burger’s Estate. A shortened version of it appeared in Genii: The International Conjurors’ Magazine, October 2017, pages 79-86.) “Be an example to the world, ever true and unwavering. Then return to the infinite.” —Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching, 28 How can I say goodbye to my dear friend Eugene Burger? How can we say goodbye to him? Eugene was beloved by nearly every magician in the world, and the outpouring of love, appreciation, and sadness since his death in Chicago on August 8, 2017, has been astonishing. The magic world grieves because we have lost a giant in our field, a genuine master: a supremely gifted performer, writer, philosopher, and teacher of magic. But we have lost something more: an extremely rare soul who inspired us to join him in elevating the art of magic. 2 There are not enough words for this remarkable man—will never be enough words. Eugene is, as he always said about his beloved art, inexhaustible. Yet the news of his death has brought, from every corner of the world, testimonies, eulogies, songs of praise, cries of lamentation, performances in his honor, expressions of love, photos, videos, and remembrances. All of it widens our perspective on the man; it has been beautiful and deeply moving. Even so, I have been asked by Eugene’s executors to write his obituary, a statement of his history, and I am deeply honored to do so. -

June 12-13, 2015 • at Auction Haversat & Ewing Galleries, LLC

June 12-13, 2015 • At Auction haversat & ewing galleries, LLC. Magicfrom the ED HILL COLLECTION Rare Books Houdini Ephemera haversat Photographs Apparatus • Postcards &Ewing Unique Correspondence haversat Galleries, LLC. &Ewing PO Box 1078 - Yardley, PA 19067-3434 Galleries, LLC. www.haversatewing.com Auction Catalog: www.haversatewing.com haversat Haversat & Ewing Galleries, LLC. &Ewing Galleries,Magic Collectibles Auction LLC. AUCTION Saturday, November 15, 2014 -11:00 AM AuctionSign-up to bid June at: www.haversatewing.com 12-13, 2015 Active bidding on all lots begin at 11:00 AM EST- Friday, June 12, 2015 First lot closes Saturday, June 13 at 3:00 PM EST. Sign-up to bid at: www.haversatewing.com HAVERSAT & EWING GALLERIES, LLC PO POBox BOX 1078 1078 - Yardley,- YARDLEY, PA PA 19067-3434 19067-3434 www.haversatewing.comWWW.HAVERSATEWING.COM A True Story: Back when Ed started collecting he befriended H. Adrian Smith, then current Dean of the Society of American Magicians. At the time, Harold as he was known to his friends, had the largest magic library in the world. Often Harold was a dinner guest at our house and as usual after our meal “the boys” would discuss magic and collecting. Harold’s plan for his books and ephemera was to donate it all to his alma mater, Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. As we all know that’s what happened to his collection. Ed on the other hand disagreed with Harold’s plan and said that when the time came for him to dissolve his library he wanted everything to be sold; so that other collectors could enjoy what he had amassed. -

Therapeutic Magic: Demystifying an Engaging Approach to Therapy

Therapeutic Magic: Demystifying an Engaging Approach to Therapy Steven Eberth, OTD, OTRL, CDP Richard Cooper, Ed.D, FAOTA, OTR Warren Hills, Ph.D, LPC, NCC ●What strategies could you use to introduce therapeutic magic with your clients? Quick Survey ●What barriers exist that may impede your ability to use therapeutic magic? History of Magic • Dr. Rich Cooper • In the beginning . ●The use of magic as a therapeutic activity has existed since World War 1 History of Magic ●Occupational therapy literature evidenced the use of therapeutic magic in 1940 History of ●Project Magic was conceived by magician, Magic David Copperfield and Julie DeJean, OTR ●In 1981, the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Daniel Freeman Center for Diagnostic and Rehabilitative Medicine in Inglewood, California piloted the use of magic History of ●In 1982, Project Magic was endorsed by the Magic American Occupational therapy Association ●The Healing of Magic program was developed History of by world renown illusionists Kevin and Cindy Magic Spencer ●In 1988, Kevin suffered injuries to his head and lower spinal cord from a near-fatal car accident ●In support of his own recovery, he worked with therapists in North Carolina on what was to become the foundation for “The Healing of Magic” ●Kevin earned Approved Provider Status from the American Occupational Therapy Association History of ●He is considered the leading authority on the therapeutic use of magic in in physical and Magic psychosocial rehabilitation https://www.spencersmagic.com/healing-of- magic/ Our Story Our humble beginning . ● How we got started ● The search for training materials begins ● What we’ve done: WMU Story ● # of students ● Grant for materials ● Resource boxes ● Documentation and reimbursement skills ● Program evaluation student surveys I am in my second fieldwork one right now at the Kalamazoo Psychiatric Hospital. -

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website: Facebook:

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website:www.OaklandMagicCircle.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/42889493580/ Password: EWeiss This Month’s Contents -. Where Are We?- page 1 - Ran’D Shines at September Lecture- page 2 - October 6 Meeting-Halloween Special -page 4 - September Performances- page 5 - Ran’D Answers Five Questions- page 9 - Phil Ackerly’s New Book & Max Malini at OMC- page 10 - Magical Resource of the Month -Black Magician Matter II-page 12 -The Funnies- page 16 - Magic in the Bay Area- Virtual Shows & Lectures – page 17 - Beyond the Bay Shows, Seminars, Lectures & Events in July- page 25 - Northern California Magic Dealers - page 32 Everything that is highlighted in blue in this newsletter should be a link that takes you to that person, place or event. WHERE ARE WE? JOIN THE OAKLAND MAGIC CIRCLE---OR RENEW OMC has been around since 1925, the oldest continuously running independent magic club west of the Mississippi. Dozens of members have gone on to fame and fortune in the magic world. When we can return to in-person meetings it will be at Bjornson Hall with a stage, curtains, lighting and our excellent new sound system. The expanding library of books, lecture notes and DVDs will reopen. And we will have our monthly meetings, banquets, contests, lectures, teach-ins plus the annual Magic Flea Market & Auction. Good fellowship is something we all miss. Until then we are proud to be presenting a series of top quality virtual lectures. A benefit of doing virtual events is that we can have talent from all over the planet and the audiences are not limited to those who can drive to Oakland. -

Magic Show! 2 Choose a Trick to Perform

EI-5166 Ages 6+ Grades 1+ MagicMagic SchoolSchool TextbookTextbook Begin magic school here! Welcome to the Magic Show! 2 Choose a trick to perform. You have just entered the exciting, magical world of illusion. Spend some time The number of stars next to the title of each trick indicates how easy a trick is studying steps 1-5 to understand how this book works. Then turn the page to begin to learn and perform. Start with the # tricks. They are easy to learn and do your magic schooling. Soon, everyone will be yelling, “How did you do that?” not require much practice. The ## tricks are easy, but require more practice. The ### tricks require more time to learn and some more practice to get the illusion just right. Study the diagram below to understand the format for Becoming a Magician the tricks. Become familiar with your props. 1 Here are the magical items included in this kit. Study the pictures and their names below. If you are learning a trick and do not know what an item is, refer back to these pictures. Magic wand Surprise Blue trick box bottle with lid Egg cup Vanishing and half egg water vase Green trick box Practice your tricks. Metal ring 4 plastic rings with loose partition 3 (red, yellow, blue) Before the day of your big performance, practice, practice, practice! Red square with hole Memorize the tricks you plan to perform. You don’t want to be looking at this and 2 plastic windows guide during your show. It’s a good idea to practice in front of a mirror, with 4 rubber bands Spring too. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

5.0-6.0 the Lost Gate Card, Orson Scott 5.8 Danny North Knew From

5.0-6.0 The Lost Gate Card, Orson Scott 5.8 Danny North knew from early childhood that his family was different, and that he was different from them. While his cousins were learning how to create the things that commoners called fairies, ghosts, golems, trolls, werewolves, and other such miracles that were the heritage of the North family, Danny worried that he would never show a talent, never form an outself. He grew up in the rambling old house, filled with dozens of cousins, and aunts and uncles, all ruled by his father. Their home was isolated in the mountains of western Virginia, far from town, far from schools, far from other people. There are many secrets in the House, and many rules that Danny must follow. There is a secret library with only a few dozen books, and none of them in English — but Danny and his cousins are expected to become fluent in the language of the books. While Danny's cousins are free to create magic whenever they like, they must never do it where outsiders might see. Unfortunately, there are some secrets kept from Danny as well. And that will lead to disaster for the North family. The Gate Thief Card, Orson Scott 5.3 In this sequel to The Lost Gate, bestselling author Orson Scott Card continues his fantastic tale of the Mages of Westil who live in exile on Earth in The Gate Thief, a novel of the Mither Mages. Here on Earth, Danny North is still in high school, yet he holds in his heart and mind all the stolen outselves of thirteen centuries of gatemages. -

Ring Report March 2017 Meeting and Dennis' Deliberation

Ring Report March 2017 Meeting and Dennis’ Deliberation Posted on March 21, 2017 by Dennis Phillips Ring Report Ring #170 “The Bev Bergeron Ring” SAM Assembly #99 March 2017 Meeting President Craig Schwarz brought our monthly meeting to order. We took a moment to remember the late Jim Zachary who recently passed on. Dan Stapleton did an update on this year’s Magicpalooza , the Florida State Magic Convention. This year called the Close-Up Conference and Competition held May 12th -14th at the Orlando/Maitland Sheraton Hotel Member Marty Kane, announced the release of his new book, “Card ChiKanery” which is loaded with great card magic. The Bev Bergeron Teach-in was the classic “Coin Through Handkerchief” which can be found in the Bobo book. Phil Schwartz presented his Magic History Moment #83, a look at his collection of letters between Charles Carter and Floyd Thayer. Carter was a Pennsylvania born illusionist who began touring the U.S. in 1906. He was trained in the legal professor and had an elegant writing style. He bought and later sold to Houdini, the Martinka’s magic business in New York and moved to San Francisco and lived in a grand house. Carter avoided the competition in America and toured his illusion show overseas on five tours until his death in Bombay, India in 1936. Carter had his illusions built by Floyd Thayer’s company in Los Angeles. Phil is a 40-year long Thayer collector and wrote the Ultimate Thayer, a comprehensive history of Thayer’s magic company. In addition to showing us, the correspondence between Carter and Thayer, Phil also showed an original Carter Egyptian theme poster nicknamed “Carter on a Camel.” It was startling to see the low prices that Carter paid Thayer for illusions back in the 1920s and early 1930s until Phil explained that we must multiply the amount by 17 times due to dollar inflation. -

A Magical Calendar for 2020 the Middle Tennessee Magic Club IBM

A Magical Calendar for 2020 compliments of The Middle Tennessee Magic Club The International Brotherhood of Magicians Ring 252 - Murfreesboro, Tennessee www.IBMring252.com “The Sam Walkoff Ring” The Middle Tennessee Magic Club (also known as The Sam Walkoff Ring) is part of the International Brotherhood of Magicians (Ring 252). We meet the first Tuesday of each month (except January & June) at 7:02 PM Central Time at the Linebaugh Library, 105 West Vine Street, in Murfreesboro, Tennessee USA. We hope you can drop by and visit us soon. It is our pleasure to offer you this special 2020 calendar with our compliments. You’ll find many of this year’s local, regional, national, and international magic events listed along with plenty of room for you to write in your own favorites. We hope you find it useful and that you think of us each time you pick it up. Below we’ve listed our Ring’s Meeting Schedule for 2020. Ring President Alan Fisher is continuing the vision he started last year of us being a Learning Ring. We’ll begin every meeting a member of the Ring presenting a mini-lecture and then a member will conduct a Teach-A-Trick. From there we’ll move into Open Time to give everybody, members & guests, a chance to perform as much as they’d like (so bring some magic to share when you visit us). Then we’ll take care of any business. Directions to our meeting location are in the back of this calendar. Our Ring also sponsors a youth magic club that continues to grow. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Picture Editing For A Structured Or Competition Program Alone Cold War August 16, 2018 Winter arrives in full force, testing the final participants like never before. Despite the elements, they’re determined to fight through the brutal cold, endless snow, and punishing hunger to win the $500,000 prize. While they all push through to their limits, at the end, only one remains. The Amazing Race Who Wants A Rolex? May 22, 2019 The Amazing Race makes a first ever trip to Uganda, where a massive market causes confusion and a labor intensive challenge on the shores of Lake Victoria exhausts teams before they battle in a Ugandan themed head-to-head competition ending in elimination. America's Got Talent Series Body Of Work May 28, 2018 Welcoming acts of any age and any talent, America’s Got Talent has remained the number one show of the summer for 13 straight seasons. American Idol Episode #205 March 18, 2019 Music industry legends and all-star judges Katy Perry, Lionel Richie and Luke Bryan travel the country between Los Angeles, New York, Denver and Louisville where incredibly talented hopefuls audition for a chance to win the coveted Golden Ticket to Hollywood in the search for the next American Idol. American Ninja Warrior Series Body Of Work July 09, 2018 American Ninja Warrior brings together men and women from all across the country, and follows them as they try to conquer the world’s toughest obstacle courses. Antiques Roadshow Ca' d'Zan, Hour 1 January 28, 2019 Antiques Roadshow transports audiences across the country to search for America’s true hidden treasure: the stories of our collective history. -

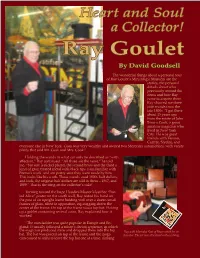

Ray Goulet by David Goodsell

Heart and Soul a Collector! Ray Goulet By David Goodsell The wonderful things about a personal tour of Ray Goulet’s Mini Magic Musuem are the stories, the personal details about who previously owned the items and how Ray came to acquire them. Ray showed me three coin wands from the late 1800s. “I got these about 15 years ago from the estate of John Brown Cook, a great amateur magician who lived in New York City. He was great friends with Vernon, Carlyle, Slydini, and everyone else in New York. Cook was very wealthy and owned two Mercedes automobiles, with vanity plates that said Mr. Cook and Mrs. Cook.” Holding the wands in what can only be described as “with affection,” Ray continued. “All three are the same,” he told me, “but one is nickel plated, the second brass and the third a kind of gray, treated metal with black tips. I am familiar with Brema’s work and am pretty sure they were made by him. This looks like his work. These wands used 1800s half dollars, and look, the original half dollars are still in them – 1867, and 1889.” That is the icing on the collector’s cake! Turning toward the huge Houdini Master Mystifier “Bur- ied Alive” poster on the south wall, Ray rested his hand on the post of an upright frame holding well over a dozen small frames of glass, tilted in opposition, zig-zagging down the center of the frame. On top of the frame was a top hat. Picking up a goblet containing several coins, Ray explained how it worked.