Post Second World War (1946–1959) OVERVIEW HISTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

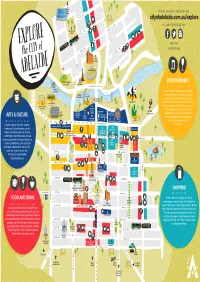

Cityofadelaide.Com.Au/Explore RYMILL NATIONAL NATIONAL

TO LE FEVRE TCE ADELAIDE AQUATIC FOR TIPS ON WHAT TO SEE AND DO VISIT CENTRE TYNTE ST cityofadelaide.com.au/explore FOLLOW CITYOFADELAIDE ON: WELLINGTON KINGSTON TCE SQUARE ARCHER ST O’CONNELL ST STANLEY ST #ADELAIDE #VISITADELAIDE WARD ST MELBOURNE ST ST PETER’S CATHEDRAL JEFFCOTT ST ADELAIDE OVAL NORTH ADELAIDE COLONEL ENTERTAINMENT GOLF COURSE LIGHT STATUE WAR MEMORIAL DRIVE TORRENS RIVER WEIR Wander through the yellow areas of the map TORRENS for a range of things to see and do for all ages, FOOTBRIDGE ROTUNDA including music, comedy, theatre, sport and POPEYE ELDER PARK ADELAIDE ZOO recreation. Check out a game at the Adelaide Oval, OLD ADELAIDE LAUNCH GAOL BONYTHON PARK take a cruise along the River Torrens, play a round PLAYSPACE ADELAIDE CASINO FESTIVAL at the North Adelaide Golf Course, visit the GOVERNMENT NATIONAL CENTRE ADELAIDE HOUSE MIGRATION WINE CENTRE Adelaide Zoo or catch a live band. There is SAHMRI CONVENTION NATIONAL MUSEUM RAILWAY ARTS & CULTURE CENTRE WAR MEMORIAL always something entertaining happening STATION BOTANIC PARLIAMENT AVE KINTORE ART GARDENS HOUSE LIBRARY MUSEUM GALLERY in the City, day and night and all NORTH TCE year round! A diverse range of museums, galleries, SAMSTAG MUSEUM LION ARTS CENTRE theatres and cultural landmarks can be MALLS BALLS AYERS HOUSE MALLS PIGS JAM FACTORY ST FROME found in the dark blue areas of the map. MERCURY CINEMA BANK ST GAWLER PL GAWLER ST PULTENEY HINDLEY ST MEDIA RESOURCE CENTRE A stroll through any of these areas will also RUNDLE MALL uncover quirky street art, famous statues and RUNDLE ST sculptures. -

Unley Heritage Research Study

UNLEY HERITAGE RESEARCH STUDY FOR THE CITY OF UNLEY VOLUME 1 2006 (updated to 2012) McDougall & Vines Conservation and Heritage Consultants 27 Sydenham Road, Norwood, South Australia 5067 Ph (08) 8362 6399 Fax (08) 8363 0121 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS UNLEY HERITAGE RESEARCH STUDY Page No 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1.2 Study Area 1.3 Objectives of Study 2.0 OVERVIEW HISTORY OF THE UNLEY DISTRICT 3 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Brief Thematic History of the City of Unley 2.2.1 Land and Settlement 2.2.2 Primary Production 2.2.3 Transport and Communications 2.2.4 People, Social Life and Organisations 2.2.5 Government 2.2.6 Work, Secondary Production and Service Industries 2.3 Subdivision and Development of Areas 2.3.1 Background 2.3.2 Subdivision Layout 2.3.3 Subdivision History 2.3.4 Sequence of Subdivision of Unley 2.3.5 Specific Historic Subdivisions and Areas 2.4 Housing Periods, Types and Styles 2.4.1 Background 2.4.2 Early Victorian Houses (1840s to 1860s) 2.4.3 Victorian House Styles (1870s to 1890s) 2.4.4 Edwardian House Styles (1900 to 1920s) 2.4.5 Inter War Residential Housing Styles (1920s to 1942) 2.4.6 Inter War and Post War Housing Styles (1942 plus) 3.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS OF STUDY 35 3.1 Planning Recommendations 3.1.1 Places of State Heritage Value 3.1.2 Places of Local Heritage Value 3.2 Further Survey Work 3.2.1 Historic Conservation Zones 3.2.2 Royal Agricultural Society Showgrounds 3.3 Conservation and Management Recommendations 3.3.1 Heritage Advisory Service 3.3.2 Preparation of Conservation Guidelines for Building Types and Materials 3.3.3 Tree Planting 3.3.4 History Centre and Council Archives 3.3.5 Heritage Incentives 4.0 HERITAGE ASSESSMENT REPORTS: STATE HERITAGE PLACES 51 4.1 Existing State Heritage Places 4.2 Proposed Additional State Heritage Places 5.0 HERITAGE ASSESSMENT REPORTS: PLACES OF LOCAL HERITAGE VALUE 171 [See Volume 2 of this Report] McDougall & Vines CONTENTS UNLEY HERITAGE RESEARCH STUDY (cont) Page No Appendices 172 1. -

City of Adelaide

City of Adelaide 1 Contents Message from CEO Mark Goldstone Message from CEO Mark Goldstone ...............................2 Despite the significant challenges we are all facing, Adelaide Fast Facts ...........................................................3 in many ways, it is still an exciting time to be in the City of Adelaide. Our city is continuing to undergo a City of Adelaide Fast Facts ..............................................3 notable transformation with new major infrastructure, Strategic Plan ....................................................................4 and exciting and creative adaptations through entrepreneurial activity. City Brand ..........................................................................4 With a vision for Adelaide to be the most liveable city Corporate Structure .........................................................5 in the world, the City of Adelaide 2020–2024 Strategic Our organisation: who we are .........................................6 Plan builds on our strengths to embrace the opportunities around us. City Governance Elected Members ...............................7 For us, a liveable city is one that is a great place to be, whether as a business owner in one of the city’s precincts, a resident or worker, a student of our Adelaide Economic Development Agency ....................8 world class universities, or a visitor to our famed festivals, cultural institutions Living in Adelaide, South Australia ................................9 and attractions. The qualities that make our city -

11Th Australian Space Forum Wednesday 31 March 2021 Adelaide, South Australia

11th Australian Space Forum Wednesday 31 March 2021 Adelaide, South Australia 11th Australian Space Forum a 11th Australian Space Forum Wednesday 31 March 2021 Adelaide, South Australia Major Sponsor Supported by b 11th Australian Space Forum c Contents Welcome from the Chair of The Andy Thomas Space Foundation The Andy Thomas Space Foundation is delighted to welcome you to the 11th Australian Space Forum. Contents 11th Australian Space Forum The Foundation will be working with partners Wednesday 31 March 2021 1 Welcome and sponsors, including the Australian Space Adelaide, South Australia — Chair of The Andy Thomas Agency, on an ambitious agenda of projects Space Foundation to advance space education and outreach. Adelaide Convention Centre, — Premier of South Australia We are reaching out to friends and supporters North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia — Head of the Australian who have a shared belief in the power of Forum sessions: Hall C Space Agency education, the pursuit of excellence and a Exhibition: Hall H commitment to diversity and inclusion. We 6 Message from the CEO The Foundation was established in 2020 for look forward to conversations during the 8 Forum Schedule the purpose of advancing space education, Forum – as well as ongoing interaction - about raising space awareness and contributing our shared interests and topics of importance 11 Speaker Profiles to the national space community. We to the national space community. are delighted that the South Australian 28 Company Profiles We hope you enjoy the 11th Australian Government has entrusted us with the future Space Forum. 75 Foundation Corporate Sponsors conduct of the Australian Space Forum – and Professional Partners Australia’s most significant space industry Michael Davis AO meeting – and we intend to ensure that the Chair, Andy Thomas Space Foundation 76 Venue Map Forum continues to be the leading national 77 Exhibition Floorplan platform for the highest quality information and discussion about space industry topics. -

Trip to Australia March 4 to April 3, 2014

TRIP TO AUSTRALIA MARCH 4 TO APRIL 3, 2014 We timed this trip so that we'd be in Australia at the beginning of their fall season, reasoning that had we come two months earlier we would have experienced some of the most brutal summer weather that the continent had ever known. Temperatures over 40°C (104°F) were common in the cities that we planned to visit: Sydney (in New South Wales), Melbourne* (in Victoria), and Adelaide (in South Australia); and _____________________________________________________________ *Melbourne, for example, had a high of 47°C (117°F) on January 21; and several cities in the interior regions of NSW, Vic, and SA had temperatures of about 50°C (122°F) during Decem ber-January. _______________________________________________________________ there were dangerous brush fires not far from populated areas. As it turned out, we were quite fortunate: typical daily highs were around 25°C (although Adelaide soared to 33°C several days after we left it) and there were only a couple of days of rain. In m y earlier travelogs, I paid tribute to m y wife for her brilliant planning of our journey. So it was this time as well. In the months leading up to our departure, we (i.e., Lee) did yeoman (yeowoman? yo, woman?) work in these areas: (1) deciding which regions of Australia to visit; (2) scouring web sites, in consultation with the travel agency Southern Crossings, for suitable lodging; (3) negotiating with Southern Crossings (with the assistance of Stefan Bisciglia of Specialty Cruise and Villas, a fam ily-run travel agency in Gig Harbor) concerning city and country tours, tickets to events, advice on sights, etc.; and (4) reading several web sites and travel books. -

EARLY COOBER PEDY SHOW HOME/DUGOUT - for SALE Coober Pedy Is a Town Steeped in the Rich History of Early Opal Mining and Its Related Industry Tourism

ISSN 1833-1831 Tel: 08 8672 5920 http://cooberpedyregionaltimes.wordpress.com Thursday 19 May 2016 EARLY COOBER PEDY SHOW HOME/DUGOUT - FOR SALE Coober Pedy is a town steeped in the rich history of early opal mining and its related industry tourism. The buying and selling of dugouts is a way of life in the Opal Capital of the World where the majority of family homes are subterranean. A strong real-estate presence has always been evident in Coober Pedy, but opal mining family John and Jerlyn Nathan with their two daughters are self-selling their historic dugout in order to buy an acreage just out of town that will suit their growing family’s needs better. The Nathan family currently live on the edge of town, a few minutes from the school and not far from the shops. Despite they brag one of most historic homes around with a position and a view from the east side of North West Ridge to be envied, John tells us that his growing family needs more space outside. “Prospector’s Dugout has plenty of space inside, with 4 bedrooms plus,” said John. “But the girls have grown in 5 years and we have an opportunity, once this property is sold, to buy an acreage outside of town, and where my daughters can have a trail bike and other outdoor activities where it won’t bother anyone.” “I will regret relinquishing our location and view but I think kids need the freedom of the outdoors when they are growing up,’ he said. John and Jeryln bought the 1920’s dugout at 720 Russell John and Jerlyn Nathan with daughters De’ Arna and Darna on the patio at Prospector’s Dugout. -

Whose Place Is It? Examining the Socio-Spatial Geography of Obesity in Young Adults for an Australian Context

Whose place is it? Examining the socio-spatial geography of obesity in young adults for an Australian context Natasha J. Howard Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours Public Health) Discipline of Geographical and Environmental Studies Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ vi LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... ix ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. xi DECLARATION .......................................................................................................................... xii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... xiii THE NOBLE STUDY ................................................................................................................. xiv ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................... xv PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS .............................................................................. -

Safety in Opal Mining Guide

Safety in Opal Mining Opal Miner’s Guide Coober Pedy Mine Rescue emergency phone number is 8672 5999. Andamooka Mine Rescue emergency phone numbers are (Police) 8672 7072, (Clinic) 8672 7087, (Post office) 8672 7007. Mintabie Mine Rescue emergency phone numbers are (clinic) 8670 5032, (SES) 8670 5162, 8670 5037 A.H. South Australia Opal Fields Disclaimer Information provided in this publication is designed to address the most commonly raised issues in the workplace relevant to South Australian legislation such as the Occupational Health Safety and Welfare Act 1986 and the Workers Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1986. They are not intended as a replacement for the legislation. In particular, WorkCover Corporation, its agents, officers and employees : • make no representations, express or implied, as to the accuracy of the information and data contained in the publication, • accept no liability for any use of the said information or reliance placed on it, and make no representations, either expressed or implied, as to the suitability of the said information for any particular purpose. Awards recognition 1999 S.A Resources Industry Awards. Judges Citation for Safety Culture Development Awarded to Safety in Opal Mining Project. ISBN: 0 9585938 5 X Cover: Opals. Black Opals Majestic Opals Safety in Opal Mining Opal miner’s guide A South Australian Project. Funded by: The Mining and Quarrying Occupational Health and Safety Committee. Project Officer: Sophia Provatidis. With input from the miners of Coober Pedy, Mintabie, Andamooka and Lambina. -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

FINAL Programme

th 68International Astronautical IAC Congress ADELAIDE, AUSTRALIA 25 - 29 SEPTEMBER 2017 FINAL PROGRAMME www.iac2017.org Industry Anchor Sponsor UNLOCKING IMAGINATION, FOSTERING INNOVATION AND STRENGTHENING SECURITY THE SKY IS NOT THE LIMIT. AT LOCKHEED MARTIN, WE’RE ENGINEERING A BETTER TOMORROW. The Orion spacecraft will carry astronauts on bold missions to the moon, Mars and beyond — missions that will excite the imagination and advance the frontiers of science. Because at Lockheed Martin, we’re designing ships to go as far as the spirit of exploration takes us. Learn more at lockheedmartin.com/orion. © 2017 LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION THE SKY IS THE LOWER LIMIT Booth #16 From deep sea to deep space, together we’re exploring the future. At sea, on land and now in space, exciting new partnerships between France and South Australia are constantly being fostered to inspire shared enterprise and opportunity. And as the International Astronautical Congress and the IAF explore ways to shape the future of aeronautics and space research, you can be sure that South Australia will be there. To find out more about opportunities for innovation and investment in South Australia visit welcometosouthaustralia.com INNOVATION THAT’S OUT OF THIS WORLD Vision and perseverance are the launch pads of innovation. Boeing is proud to salute those who combine vision with passion to turn dreams into reality. Contents 1. Welcome Messages ____________________________________________________________________________ 2 1.1 Message from the President of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) ............................................. 2 1.2 Message from the Local Organising Committee (LOC) ....................................................................................... 3 1.3 Message from the International Programme Committee (IPC) Co-Chairs ......................................................... -

THE MAKING of the NEWCASTLE INDUSTRIAL HUB 1915 to 1950

THE MAKING OF THE NEWCASTLE INDUSTRIAL HUB 1915 to 1950 Robert Martin Kear M.Bus. (University of Southern Queensland) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of a Master of Philosophy in History January 2018 This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that the work embodied in the thesis is my own work, conducted under normal supervision. The thesis contains no material which has been accepted, or is being examined, for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 and any approved embargo. Robert Kear ii ABSTRACT Aim of this Thesis The aim of this thesis is to chart the formation of the Newcastle Industrial Hub and to identify the men who controlled it, in its journey from Australian regional obscurity before 1915, to be the core of Australian steel manufacturing and technological development by 1950. This will be achieved through an examination of the progressive and consistent application of strategic direction and the adoption of manufacturing technologies that progressively lowered the manufacturing cost of steel. This thesis will also argue that, coupled with tariff and purchasing preferences assistance, received from all levels of government, the provision of integrated logistic support services from Newcastle’s public utilities and education services underpinned its successful commercial development. -

Regolith-Landforms and Plant Biogeochemical Expression of Buried Mineralisation Targets in the Northern Middleback Ranges, (“Iron Knob South”) South Australia

Regolith-Landforms and plant biogeochemical expression of buried mineralisation targets in the Northern Middleback Ranges, (“Iron Knob South”) South Australia Louise Thomas Geology and Geophysics, School of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Adelaide, Adelaide SA 5005, Australia A manuscript submitted for the Honours Degree of Bachelor of Science, University of Adelaide, 2011 Supervised by Dr. Steven M. Hill 2 ABSTRACT South of the town Iron Knob on the northern Eyre Peninsula, a tenement scale plant biogeochemical survey and regolith-landform mapping, combined to define areas with elevated Cu, Zn and Au contents that are worthy of follow-up exploration. Plant biogeochemistry was conducted within a 6 Km2 area with 1 Km spacing between each E-W trending transect and 200 m spacing between each sample. A regolith-landform map presents the distribution of regolith materials and associated landscape processes to help constrain geochemical dispersion. A Philips XL30 SEM provided insight into how the plants uptake certain elements and distribute them within the organs structure. Two zones of elevated trace metals (e.g. Cu, Au and Zn) were defined either side of a NW-SE structure crossing over the N-S trending „Katunga‟ ridge. Both targets were located on similar regolith-landform units of sheet-flood fans and alluvial plains. Copper and Zn results were best represented by the western myall species while the bluebush species was best at detecting Au. A follow up study targeting the NW-SE structure with closer sample spacing is recommended in further constraining drilling targets. For the tenement holding company, Onesteel Ltd, these results are significant as they define two new areas of interest for possible IOCG mineralisation.