How Can Research Into Cycling Help Implement the National Cycling Strategy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventure Cyclist GO the DISTANCE

WAYPOINTS 8 MECHANICAL ADVANTAGE 56 OPEN ROAD GALLERY 63 ADVENTURE CYCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. APRIL 2011 WWW.ADVentURecYCLing.ORG $4.95 The Second Annual Cyclists’ Travel Guide INSIDE: 2011 TOURING BIKE BUYEr’s GUIDE | KEEPING THE KIDS HAPPY GPS AND E-MAPPING | THE MIRROR LEGEND SHARE THE JOY GET A CHANCE TO WIN Spread the joy of cycling and get a chance to win cool prizes n For every cyclist you sign up through a gift membersip or who joins through your referral, you score one entry to win a Novara Verita (rei.com/ product/807242) valued at over $1,100. The winner will be drawn from all eligible members in January of 2012. n Recruit the most new members in 2011, and you’ll win a $500 Adventure Cycling shopping spree. n Each month we’ll draw a mini-prize winner who will receive gifts from companies like Old Man Mountain, Cascade Designs, Showers Pass, and others. n The more new members you sign up, the more chances you have to win! Adventure Cycling Association adventurecycling.org/joy Adventure Cycling Corporate Members Adventure Cycling’s business partners play a significant level of support. These corporate membership funds go toward role in the success of our nonprofit organization. Our Corporate special projects and the creation of new programs. To learn more Membership Program is designed to spotlight these key support- about how your business can become a corporate supporter of ers. Corporate Members are companies that believe in what we Adventure Cycling, go to www.adventurecycling.org/corporate or do and wish to provide additional assistance through a higher call (800) 755-2453. -

Trinidad and Tobago Cycling Federation (TTCF) Continue to See a Rebirth in Cycling Over the Last Couple of Years

Original Date: Page I Policy & Procedures for the Selection of Cyclists and Officials April 2007 TRINIDAD & TOBAGO to Represent Trinidad & Tobago at Local & Foreign TTCF-SP-001 Revision Date: CYCLING FEDERATION International Competitions Revision May 21, 2018 #111 Policy and Procedures for the Selection of Cyclists and Officials to Represent Trinidad and Tobago At Local & Foreign International Competitions APPROVED BY COUNCIL May 21, 2018 – Version 111 Original Date: Policy & Procedures for the Selection of Cyclists and Officials Page II April 2007 TRINIDAD & TOBAGO to Represent Trinidad & Tobago at Local & Foreign Revision Date: TTCF-SP-001 CYCLING FEDERATION International Competitions 22 Jul 2017 Revision #11 POLICY AND PROCEDURES FOR THE SELECTION OF CYCLISTS AND OFFICIALS TO REPRESENT TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO AT LOCAL AND FOREIGN INTERNATIONAL COMPETITIONS BACKGROUND As the Trinidad and Tobago Cycling Federation (TTCF) continue to see a rebirth in cycling over the last couple of years. It is now more important as an organization to become transparent and open in our National Team selections. As such, the Federation saw the increased need to ensure that proper structures, policies and procedures are put in place to ensure fair selection processes are established as we move forward. The Government of Trinidad and Tobago has identified cycling as one of the fourteen sporting activities that is to receive special support over the short and medium terms. The sport therefore, has the potential to benefit from this recognition and the formulation and proper documentation of policies and procedures within the fraternity is one important step in capitalizing on the opportunity present themselves. The TTCF has recognized the need for formulating this policy and has initiated this effort to prepare and document it. -

Bicycles BALLINA Pirie Honda POAT PIRIE Quality Cycles Plus Btjranda Mallard Cycles SALE Eclipse Ski & Cycles MITTAGONG S.J

I 12 SPEED TRI-A The Tri-A features tight racing geometry for quick response, made of TangeDB Chro-Moly tubing and incorporates internal brake and derailleur wiring. Shimano 600EX throughout, Araya hard anodised rims and Panaracer Tri Sport tyres make this the intelligent choice for the discerning cyclist. 15 SPEED CRESTA A touring bicycle to the .end. The Cresta is builtwith emphasis on long distance touring. Frame features Tange No.2 and No.5 Cro Mo tubing, three biddon holders and extra eyelets to accommodate carriers. Drive train is Sugino TRT coupled to the new Suntour Mountech Tri pulley derailleur. Cantilever brakes, 40 spoke rear wheel and rear carrier completes this fine touring bicycle. Available from leading cycle deµlers REPC:D C:YC:LES Subscribe toFreewheeling the certain way to keep in touch with the world of bicycling. a copy. That way you want find us Someone beat you to it? Are you tired hard to get. Freewheeling Subscription of flicking through mountains of To subscribe to Freewheeling Rates paper at your local newsagent simply clip the order form below (or One year Introductory (6 issues) looking for the next glossy copy of make a photo copy if you don't want $12.00 Freewheeling? to defgace your mag and post to our One Year ordinary (6 issues) $15.00 For the introductory price of$12.00 Freepost address. Please note Two Year Special (12 issues) $24.00 (save 20 percent) for 6 issues you can letters to our Freepost $21.00 have Freewheeling delivered to your address do not require a One Year overseas surface home address protected from the postage stamp if posted in One Year overseas air mail (NZ, elements in a sealed plastic bag six Australia. -

Sample M525.Pdf

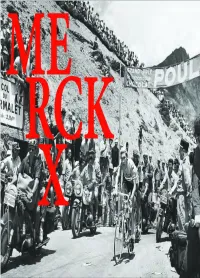

Copyright © 2012 by VeloPress First English-language edition First published as Merckx 525, copyright © 2010 by Uitgeverij Kannibaal, Lichtervelde, Belgium All rights reserved. Printed in China. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100, Boulder, CO 80301-2338 USA Phone (303) 440-0601 • Fax (303) 444-6788 • E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merckx 525. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-934030-89-9 (hardcover: alk. paper) 1. Merckx, Eddy, 1945– 2. Cyclists—Belgium—Biography. GV1051.M43M47 2012 796.6092—dc23 [B] 2012015371 This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. 12 13 14 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 001-224_Merckx_US_FNL.indd ii 5/24/12 2:44 PM CONTENTS 5 Prologue by Eddy Merckx 128 Death rides along 1970: Tour de France, Gap–Mont Ventoux 7 A phenomenon by Karl Vannieuwkerke 140 Nothing is as it used to be 28 Edouard’s fi rst 1971: Tour de France: The duel with Ocaña 1961: Novice race, Petit-Enghien 144 Cut to the quick 36 The fi rst achievement 1971: World Championship, Mendrisio 1964: Amateur World Championship, -

~R~Wheeling FREE • NE CAIALIGIE

.~r~wheeling FREE • NE CAIALIGIE BICYCLE HELMETS 11amar1111 SllfflJ SNRT Coumdown1o Seoul FATTYRES Ra•1o1he Rodi colour pho1os TRAVEL ~,... Cycltn1tn En1land IONADI Compu1tn1 across Amenca Registered by Australia Post Publication No NBH2266 July 1988 esigned 1011ne senous ott- 1oode1, 1ne new eignleen Dspeed 1-\igl"I Sie!!O'S on\V nrnilolion is 1ne 1ide1 .1ne norne. toll<.. siern and nondle-bO! oie rnode ot p1erniutn cn10-rnolV. o pertecl balance ot ligl"IIWeigl"II and du1obililV, Md 10 lnis cornPonenls sucn as Snirnono oeoie SIS indexing svsiern , Snirnono Sio-Poce cionK sel. NOVO o\\OV nrns will"I QR sealed beefing nubs and you nO\/e on ,t>.1S 1nol will loKe you onywneie you wonl 10 go. and bocK. (08'~ ~~~~, REPCOCYC 25 HAMILTON S}ES HUNTINGDALE, 3166 Available from leading Repco Cycle dea lers. Freewheelina Columns Number SO July/Auaust 1188 Travel and touring 82 CALENDAR 34 ENGLISH HISTORY • CLASSIFIEDS Contents RECYCLED I JOHN DRUNNOND Features Peaceful touring in old 3 DON HATCHER 16 WEIRDAND England 15 PRO DEALERS WONDERFUL 38 THE GREAT BRITISH 5 WARREN SALOMON Your future hike is readv BINERIDE 76 PHIL SONERYILLE - well, almost · It's not a ride, it's an event! 43 AROUND IRELAND II WORLD AWHEEL 20 HOWTONEEP IN LOW GEAR Freewhee ling is published seven times a year in the AHEAD months of January, March, May, July, September, October A guide to bicycle helmets Eric Newby 's latest hook and November. ISSN No: 0 156 4579. Edito rial and Advertising Offices: Room 57 Trades Hall, cnr Dixon 21 COMPUTING 56 WHEN ONE LAP IS & Goulburn Sts., Sydney NSW Australia. -

I Can Ride! Ebook

I CAN RIDE! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lynn Maslen Kertell,Sue Hendra | 32 pages | 25 Jan 2013 | Scholastic | 9780545382724 | English | United States I Can Ride! PDF Book Becky rated it liked it Sep 02, Cyclocross races feature man-made features such as small barriers which riders either bunny hop over or dismount and walk over. Germany used bicycles again in World War II, while the British employed airborne "Cycle-commandos" with folding bikes. In , Charles Minthorn Murphy became the first man to ride his bicycle a mile in under a minute hence his nickname, Mile-a-Minute Murphy , which he did by drafting a locomotive at New York 's Long Island. The provision of cycling infrastructure varies widely between cities and countries, particularly since cycling for transportation almost entirely occurs in public streets. Download as PDF Printable version. Get a physical. Bicycle tourism has been one of the most popular sports for recreational benefit. After years of walking alongside me, holding the back of my seat, they took drastic measures. Even the car industry uses bicycles. An English study recruiting non-cyclist older adults aged 50 to 83 to participate as either conventional pedal bike cyclists, electrically assisted e-bike cyclists, or a non-cyclist control group in outdoor trails measured cognitive function through executive function, spatial reasoning, and memory tests and well-being through questionnaires. Critical Mass is an event typically held on the last Friday of every month in cities around the world where bicyclists take to the streets en masse. Cookie Settings. For the hockey strategy, see Cycling ice hockey. -

A Behavioral Law and Economics Approach to Legal Regulation of Doping in Sports Shayna M

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 19 Article 7 Issue 1 Fall Are We All Dopes? A Behavioral Law and Economics Approach to Legal Regulation of Doping in Sports Shayna M. Sigman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Shayna M. Sigman, Are We All Dopes? A Behavioral Law and Economics Approach to Legal Regulation of Doping in Sports, 19 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 125 (2008) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol19/iss1/7 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARE WE ALL DOPES? A BEHAVIORAL LAW & ECONOMICS APPROACH TO LEGAL REGULATION OF DOPING IN SPORTS SHAYNA M. SIGMAN* INTRODUCTION You should care about the prevalence of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) and doping methods currently being used and abused within elite sports. You should care, not because teenagers and youth are harmed by this, even though they most likely are. 1 You should care, not because elite athletes or those attempting to become elite athletes are harmed by this, even though they most likely are. 2 Whether you are a recreational athlete or a couch potato, whether you are a serious sports fan, a casual fan, or not a fan at all, you should care about the fact that it is highly likely that you have been harmed by doping in sports. Associate Professor of Law, Jacob D. Fuchsberg Touro Law Center. -

2017 Station Blvd Transportation Plan Update

City of Aurora Station Boulevard Transit-Oriented Development – Transportation Plan Update December 5, 2017 Prepared in Partnership by: The Regional Transportation Authority The City of Aurora, IL Project Background and Overview The Station Boulevard Transportation Plan Update, completed by the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) through its Community Planning Program, and in partnership with the City of Aurora (City), examines multi-modal connections to the Route 59 Metra station for residential neighborhoods along Station Boulevard. Local knowledge, input and guidance was provided through the development of this plan by a steering committee comprised of representatives from the neighborhood, including residents and developers, as well as Metra staff. Additionally, Pace Suburban Bus and BNSF Railway staff offered technical assistance as needed through the duration of the project. The Station Boulevard Corridor is a Transit-Oriented Development located just south of the Route 59 Metra Station in Aurora. Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) is defined by the RTA as moderate to high-density, mixed-use communities located within close proximity of a rail or bus station designed to maximize walkability and transit access. TOD provides residents with increased mobility options, a variety of commercial outlets and jobs within a short distance of their homes while the compact style of development preserves open space. The Route 59 station is served by Metra Commuter Rail, connecting the residents along Station Boulevard with Downtown Chicago and points in between. This plan recommends multi-modal improvements that will enhance resident access to and from the station and is an update to the “Station Boulevard Shuttle” plan developed in 2009 for the City. -

Cycle Freight in London: a Scoping Study

Transport for London Cycle freight in London: A scoping study MAYOR OF LONDON Transport for London 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This project has laid the foundations that could enable Transport for London to introduce trials of load carrying bikes in a variety of freight roles. We have successfully engaged with a large number of stakeholders (exceeding our proposal estimate), who have expressed real interest in taking further the concept of cycle freight as part of the delivery infrastructure. In summary: Case studies have been completed on existing users of cycles, including three „cycle freight‟ operators, plus the Royal Mail and a cycle messenger firm. Interviews were conducted with two „own account‟ delivery fleet operators, and three third party carriers. Five potential pilot projects have been outlined. Interviews were conducted with the managers of two shopping centres, and a potential local delivery partner was identified for a pilot home delivery scheme. Valuable contacts were made with a variety of public sector bodies with a view to developing work on their internal mail operations. In addition, this report identifies one trial that is now taking place the work of this project has led to a large stationery supplier obtaining their senior management‟s approval for a major trial of the use of cycles. Finally, this report also identifies a potential model for a large-scale, London-wide approach to cycle delivery, based on La Petite Reine in France, and suggests key individuals to approach in carrying out further research. General conclusions about cycle freight The project proposal outlined the advantages and disadvantages of using cycles to move some types of freight and, in the light of these posed the question, “Given the apparent potential benefits of using cycles to move freight in cities like London, why is their use not more widespread?” It was suggested that there would be both practical and „human‟ factors to be investigated – issues around the general perception or attitude to the use of cycles in this type of work. -

Freewheeling44-SCREE

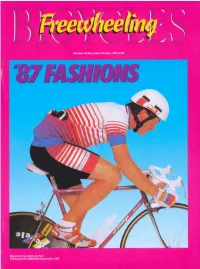

t Australia Post ber RegiSPublicationer~d by No NBH2266 Septem . 1987 t 12 SPEED TRI-A The Tri-A features tight racing geometry for quick response, made of Tange DB Chro-Moly tubing and incorporates internal brake and derailleur wiring. Shimano 600EX throughout, Araya hard anodised rims and Panaracer Tri Sport tyres make this the intelligent choice for the discerning cyclist. 15 SPEED CRESTA A touring bicycle to the .end. The Cresta 7s builtwith emphasis on long distance touring. Frame features Tange No.2 and No.5 Cro Mo tubing, three biddon holqefS and extra eyelets to accommodate carriers. Drive train is Sugino TRT coupled to the new Suntour Mountech Tri pulley derailleur. Cantilever brakes, 40 spoke rear wheel and rear carrier completes this fine touring bicycle. • - - , Available from leading cycle dealers REPC:D C:YC:LES Number 44 September/October 1987 Contents 47 MOTOR MOUSE BECOMES SUPER CAT Danny Clark - six day champ 8ic1Jcle Traflel and Columns transport 5 W ARREN SALOMON 42 REFLECTIONS 6 DONHATCHER John Brown looks back 7 JOHNDR UMMOND at his US bike odyssey 12 PRO DEALERS 46 RIGHTSOF ACCESS 10 WRITE ON Every street is a bicycle 15 THE WORLD AWHEEL street 29 PHIL SOMERVILLE 8ic1Jcle clothin9 feature 68 CLASSIFIEDS 21 SUMMER FASHION 69 CALENDAR 1987/88 A four page colour feature Freewheeling is published six times a year in the months of January, 27 THE BIKES OF SUMMER March, May, July, September and Nove mber. ISSN No: 0156 4579 , Editorial and Advertising Offices: Room 57Trades Hall , cnr Dixon & This season's bike Goulburn Sts ., Sydney NS WAustralia. -

Alejandro Valverde Belmonte V. Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano

Court of Arbitration for Sport CAS 2009/A/1879 – Alejandro Valverde Belmonte v. Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano CAS 2009/A/1879 Alejandro Valverde Belmonte v. Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano ARBITRAL AWARD Rendered by the: COURT OF ARBITRATION FOR SPORT Composed of the following members: President: Mr. Romano Subiotto QC, Attorney-Solicitor, Brussels, Belgium and London, United Kingdom Arbitrators: Mr. Ruggero Stincardini, Attorney, Perugia, Italy Mr. Ulrich Haas, Professor, Zürich, Switzerland Ad hoc clerk: Mr. Pierantonio D’Elia, Attorney, Rome, Italy and Brussels, Belgium In the arbitral appeal proceedings between MR. ALEJANDRO VALVERDE BELMONTE, Murcia, Spain Represented by Mr. José Rodríguez, Madrid, Spain and Mr. Federico Cecconi, Milan, Italy - Appellant - versus COMITATO OLIMPICO NAZIONALE ITALIANO (CONI), Rome, Italy Represented by Mr. Ettore Torri, General Public Prosecutor - First respondent - WORLD ANTI-DOPING AGENCY (WADA), Lausanne, Switzerland Represented by Mr. Stephen Drymer, Montréal, Canada - Second respondent - INTERNATIONAL CYCLING UNION (UCI), Aigle, Switzerland Represented by Mr. Philippe Verbiest, Leuven, Belgium and Mr. Pablo Jimenez of Parga, Madrid, Spain - Third respondent - * * * This translation is provided for information purposes only. Court of Arbitration for Sport CAS 2009/A/1879 – Alejandro Valverde Belmonte v. Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano I. THE PARTIES 1 II. FACTS 1 A. PROCEEDINGS IN SPAIN 1 B. PROCEEDINGS IN ITALY 4 III. SUMMARY OF PROCEEDINGS BEFORE CAS 8 IV. LAW 13 A. JURISDICTION OF CAS AND ADMISSIBILITY OF THE APPEAL 13 B. POWER OF EXAMINATION 13 C. APPLICABLE LAW 14 1. On the merits 14 2. On the proceedings 16 D. JURISDICTION OF CONI 16 E. ADMISSIBILITY OF EVIDENCE 18 1. Rules regulating the eligibility of evidence before CAS 18 2. -

Ewheeling F.Lililesi 1 • • ! I !I I L '

~r,~ewheeling F.lililESI 1 • • ! I !I I L ' .• lliliEI Homelnainen ilillllEI! ili1t111linlw. IH1e11n ar.lillour. RKCIII Summer. lnacli. car.011a1s esigned 1011ne senous ott- 1oode1, 1ne new eignleen Dspeed 1-\igl"I Sie!!O'S on\V nrnilolion is 1ne 1ide1 .1ne norne. toll<.. siern and nondle-bO! oie rnode ot p1erniutn cn10-rnolV. o pertecl balance ot ligl"IIWeigl"II and du1obililV, Md 10 lnis cornPonenls sucn as Snirnono oeoie SIS indexing svsiern , Snirnono Sio-Poce cionK sel. NOVO o\\OV nrns will"I QR sealed beefing nubs and you nO\/e on ,t>.1S 1nol will loKe you onywneie you wonl 10 go. and bocK. (08'~ ~~~~, REPCOCYC 25 HAMILTON S}ES HUNTINGDALE, 3166 Available from leading Repco Cycle dea lers. Freewheelin1 Contents Mountain bikes Fitness Number 49 Nay/June 1188 50 NIB'S UP NOUNT 26 KEEPING FIT KENYA Columns INDOORS Mountain madness on 61 CALENDAR A guide to home trainers the dark continent 68 CLASSIFIEDS 3 2 FITNESS AS 52 DESERT CHALLENGE I JOHN DRUNNOID TRANSPORT BECOMES A RACE TO 26 DON HATCHER Putting your commuter THE ROCK • PRO DEALERS kilometres to good use Floods alter course of 5 WARREN SALOMON Travel and touring Simpson race 45 PHIL SONERYILLE 20 TWO PLAN FOR Bicycle sport II WORLD AWHEEL THREE 01 WORLD 28 SIX DAYS AID Freewheeling is published seven times a year in the months of January, TOUR March, May, July, September, October and Novem ber. ISSN No: 0156 SORE MUSCLES •579, Ed itori•I and Advertising Offices: Room 57 Trades Hall , cnr 34 THE OTHER SIDE OF A six day triathlon run in Dixon & Goulborn Sts., Sydney NSW Austrafa Address al l correspondence to: Freewheeling PO Box K26 , Haymarket NSW 2000 Austra li a THE BLACK STUNP the hills and rivers near Telephone (02) 26• 85-+4.