Adaptive Functions of the Corpus Striatum: the Past and Future of the R-Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Function and the Frontal Lobes: a Meta-Analytic Review

Neuropsychology Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, March 2006 (C 2006) DOI: 10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x Executive Function and the Frontal Lobes: A Meta-Analytic Review Julie A. Alvarez1 and Eugene Emory2 Published online: 1 June 2006 Currently, there is debate among scholars regarding how to operationalize and measure executive functions. These functions generally are referred to as “supervisory” cognitive processes because they involve higher level organization and execution of complex thoughts and behavior. Although conceptualizations vary regarding what mental processes actually constitute the “executive function” construct, there has been a historical linkage of these “higher-level” processes with the frontal lobes. In fact, many investigators have used the term “frontal functions” synonymously with “executive functions” despite evidence that contradicts this synonymous usage. The current review provides a critical analysis of lesion and neuroimaging studies using three popular executive function measures (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Phonemic Verbal Fluency, and Stroop Color Word Interference Test) in order to examine the validity of the executive function construct in terms of its relation to activation and damage to the frontal lobes. Empirical lesion data are examined via meta-analysis procedures along with formula derivatives. Results reveal mixed evidence that does not support a one-to-one relationship between executive functions and frontal lobe activity. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications of construing the validity of these neuropsychological tests in anatomical, rather than cognitive and behavioral, terms. KEY WORDS: Executive function; Frontal lobe; Neuropsychology; Meta-analysis. Executive functions generally refer to “higher-level” ropsychological processes involving (a) cognitive flexi- cognitive functions involved in the control and regulation bility, (b) problem-solving, and (c) response maintenance of “lower-level” cognitive processes and goal-directed, (Greve et al., 2002). -

Neuromodulators and Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in Learning and Memory: a Steered-Glutamatergic Perspective

brain sciences Review Neuromodulators and Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in Learning and Memory: A Steered-Glutamatergic Perspective Amjad H. Bazzari * and H. Rheinallt Parri School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-(0)1212044186 Received: 7 October 2019; Accepted: 29 October 2019; Published: 31 October 2019 Abstract: The molecular pathways underlying the induction and maintenance of long-term synaptic plasticity have been extensively investigated revealing various mechanisms by which neurons control their synaptic strength. The dynamic nature of neuronal connections combined with plasticity-mediated long-lasting structural and functional alterations provide valuable insights into neuronal encoding processes as molecular substrates of not only learning and memory but potentially other sensory, motor and behavioural functions that reflect previous experience. However, one key element receiving little attention in the study of synaptic plasticity is the role of neuromodulators, which are known to orchestrate neuronal activity on brain-wide, network and synaptic scales. We aim to review current evidence on the mechanisms by which certain modulators, namely dopamine, acetylcholine, noradrenaline and serotonin, control synaptic plasticity induction through corresponding metabotropic receptors in a pathway-specific manner. Lastly, we propose that neuromodulators control plasticity outcomes through steering glutamatergic transmission, thereby gating its induction and maintenance. Keywords: neuromodulators; synaptic plasticity; learning; memory; LTP; LTD; GPCR; astrocytes 1. Introduction A huge emphasis has been put into discovering the molecular pathways that govern synaptic plasticity induction since it was first discovered [1], which markedly improved our understanding of the functional aspects of plasticity while introducing a surprisingly tremendous complexity due to numerous mechanisms involved despite sharing common “glutamatergic” mediators [2]. -

Synaptic Organization of Claustral and Geniculate Afferents to the Visual Cortex of the Cat

The Journal of Neuroscience December 1986, 6(12): 3564-3575 Synaptic Organization of Claustral and Geniculate Afferents to the Visual Cortex of the Cat Simon LeVay Robert Bosch Vision Research Center, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego, California 92138 Claustral and geniculate afferents to area 17 were labeled by sponses of some cortical neurons, previously called “hypercom- anterograde axonal transport of peroxidase-conjugated wheat- plex cells” by Hubel and Wiesel (1965), are suppressed as the germ agglutinin, and examined in the electron microscope. A length of the stimulating slit of light is extended beyond some peroxidase reaction protocol that led to labeling in the form of optimal value. Interestingly, neurons in the visual claustrum minute holes in the EM sections was used. Both types of affer- behave in a complementary fashion: Their responses to an ori- ents formed type 1 (presumed excitatory) synapses exclusively. ented stimulus increase monotonically with stimulus length, In agreement with previous reports the great majority of genic- sometimes showing length summation up to 40” or more-a ulate afferents to layers 4 and 6 contacted dendritic spines. The sizable portion of the animal’s entire field of view (Sherk and claustral afferents to layers 1 and 6 also predominantly con- LeVay, 198 1). tacted spines. In layer 4, however, claustral afferents contacted These observations suggest that claustral neurons contribute spines and dendritic shafts about equally. The results suggest a to end-stopping by exerting a length-dependent inhibition on substantial Claus&al input to smooth-dendrite cells in layer 4, some neurons in the visual cortex. -

The Effect of Nucleus Basalis Magnocellularis Deep Brain

Lee et al. BMC Neurology (2016) 16:6 DOI 10.1186/s12883-016-0529-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The effect of nucleus basalis magnocellularis deep brain stimulation on memory function in a rat model of dementia Ji Eun Lee1†, Da Un Jeong1†, Jihyeon Lee1, Won Seok Chang2 and Jin Woo Chang1,2* Abstract Background: Deep brain stimulation has recently been considered a potential therapy in improving memory function. It has been shown that a change of neurotransmitters has an effect on memory function. However, much about the exact underlying neural mechanism is not yet completely understood. We therefore examined changes in neurotransmitter systems and spatial memory caused by stimulation of nucleus basalis magnocellularis in a rat model of dementia. Methods: We divided rats into four groups: Normal, Lesion, Implantation, and Stimulation. We used 192 IgG-saporin for degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neuron related with learning and memory and it was injected into all rats except for the normal group. An electrode was ipsilaterally inserted in the nucleus basalis magnocellularis of all rats of the implantation and stimulation group, and the stimulation group received the electrical stimulation. Features were verified by the Morris water maze, immunochemistry and western blotting. Results: AllgroupsshowedsimilarperformancesduringMorriswater maze training. During the probe trial, performance of the lesion and implantation group decreased. However, the stimulation group showed an equivalent performance to the normal group. In the lesion and implantation group, expression of glutamate acid decarboxylase65&67 decreased in the medial prefrontal cortex and expression of glutamate transporters increased in the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. However, expression of the stimulation group showed similar levels as the normal group. -

Multiplexed Neurochemical Signaling by Neurons of the Ventral Tegmental

Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy 73 (2016) 33–42 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jchemneu Multiplexed neurochemical signaling by neurons of the ventral tegmental area David J. Barker, David H. Root, Shiliang Zhang, Marisela Morales* Neuronal Networks Section, Integrative Neuroscience Research Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 251 Bayview Blvd Suite 200, Baltimore, MD 21224, United States A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is an evolutionarily conserved structure that has roles in reward- Received 26 June 2015 seeking, safety-seeking, learning, motivation, and neuropsychiatric disorders such as addiction and Received in revised form 31 December 2015 depression. The involvement of the VTA in these various behaviors and disorders is paralleled by its Accepted 31 December 2015 diverse signaling mechanisms. Here we review recent advances in our understanding of neuronal Available online 4 January 2016 diversity in the VTA with a focus on cell phenotypes that participate in ‘multiplexed’ neurotransmission involving distinct signaling mechanisms. First, we describe the cellular diversity within the VTA, Keywords: including neurons capable of transmitting dopamine, glutamate or GABA as well as neurons capable of Reward multiplexing combinations of these neurotransmitters. Next, we describe the complex synaptic Addiction Depression architecture used by VTA neurons in order to accommodate the transmission of multiple transmitters. Aversion We specifically cover recent findings showing that VTA multiplexed neurotransmission may be mediated Co-transmission by either the segregation of dopamine and glutamate into distinct microdomains within a single axon or Dopamine by the integration of glutamate and GABA into a single axon terminal. -

Basal Ganglia & Cerebellum

1/2/2019 This power point is made available as an educational resource or study aid for your use only. This presentation may not be duplicated for others and should not be redistributed or posted anywhere on the internet or on any personal websites. Your use of this resource is with the acknowledgment and acceptance of those restrictions. Basal Ganglia & Cerebellum – a quick overview MHD-Neuroanatomy – Neuroscience Block Gregory Gruener, MD, MBA, MHPE Vice Dean for Education, SSOM Professor, Department of Neurology LUHS a member of Trinity Health Outcomes you want to accomplish Basal ganglia review Define and identify the major divisions of the basal ganglia List the major basal ganglia functional loops and roles List the components of the basal ganglia functional “circuitry” and associated neurotransmitters Describe the direct and indirect motor pathways and relevance/role of the substantia nigra compacta 1 1/2/2019 Basal Ganglia Terminology Striatum Caudate nucleus Nucleus accumbens Putamen Globus pallidus (pallidum) internal segment (GPi) external segment (GPe) Subthalamic nucleus Substantia nigra compact part (SNc) reticular part (SNr) Basal ganglia “circuitry” • BG have no major outputs to LMNs – Influence LMNs via the cerebral cortex • Input to striatum from cortex is excitatory – Glutamate is the neurotransmitter • Principal output from BG is via GPi + SNr – Output to thalamus, GABA is the neurotransmitter • Thalamocortical projections are excitatory – Concerned with motor “intention” • Balance of excitatory & inhibitory inputs to striatum, determine whether thalamus is suppressed BG circuits are parallel loops • Motor loop – Concerned with learned movements • Cognitive loop – Concerned with motor “intention” • Limbic loop – Emotional aspects of movements • Oculomotor loop – Concerned with voluntary saccades (fast eye-movements) 2 1/2/2019 Basal ganglia “circuitry” Cortex Striatum Thalamus GPi + SNr Nolte. -

Amygdaloid Projections to the Ventral Striatum in Mice: Direct and Indirect Chemosensory Inputs to the Brain Reward System

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 22 August 2011 NEUROANATOMY doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00054 Amygdaloid projections to the ventral striatum in mice: direct and indirect chemosensory inputs to the brain reward system Amparo Novejarque1†, Nicolás Gutiérrez-Castellanos2†, Enrique Lanuza2* and Fernando Martínez-García1* 1 Departament de Biologia Funcional i Antropologia Física, Facultat de Ciències Biològiques, Universitat de València, València, Spain 2 Departament de Biologia Cel•lular, Facultat de Ciències Biològiques, Universitat de València, València, Spain Edited by: Rodents constitute good models for studying the neural basis of sociosexual behavior. Agustín González, Universidad Recent findings in mice have revealed the molecular identity of the some pheromonal Complutense de Madrid, Spain molecules triggering intersexual attraction. However, the neural pathways mediating this Reviewed by: Daniel W. Wesson, Case Western basic sociosexual behavior remain elusive. Since previous work indicates that the dopamin- Reserve University, USA ergic tegmento-striatal pathway is not involved in pheromone reward, the present report James L. Goodson, Indiana explores alternative pathways linking the vomeronasal system with the tegmento-striatal University, USA system (the limbic basal ganglia) by means of tract-tracing experiments studying direct *Correspondence: and indirect projections from the chemosensory amygdala to the ventral striato-pallidum. Enrique Lanuza, Departament de Biologia Cel•lular, Facultat de Amygdaloid projections to the nucleus accumbens, olfactory tubercle, and adjoining struc- Ciències Biològiques, Universitat de tures are studied by analyzing the retrograde transport in the amygdala from dextran València, C/Dr. Moliner, 50 ES-46100 amine and fluorogold injections in the ventral striatum, as well as the anterograde labeling Burjassot, València, Spain. found in the ventral striato-pallidum after dextran amine injections in the amygdala. -

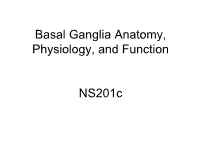

Basal Ganglia Anatomy, Physiology, and Function Ns201c

Basal Ganglia Anatomy, Physiology, and Function NS201c Human Basal Ganglia Anatomy Basal Ganglia Circuits: The ‘Classical’ Model of Direct and Indirect Pathway Function Motor Cortex Premotor Cortex + Glutamate Striatum GPe GPi/SNr Dopamine + - GABA - Motor Thalamus SNc STN Analagous rodent basal ganglia nuclei Gross anatomy of the striatum: gateway to the basal ganglia rodent Dorsomedial striatum: -Inputs predominantly from mPFC, thalamus, VTA Dorsolateral striatum: -Inputs from sensorimotor cortex, thalamus, SNc Ventral striatum: Striatal subregions: Dorsomedial (caudate) -Inputs from vPFC, hippocampus, amygdala, Dorsolateral (putamen) thalamus, VTA Ventral (nucleus accumbens) Gross anatomy of the striatum: patch and matrix compartments Patch/Striosome: -substance P -mu-opioid receptor Matrix: -ChAT and AChE -somatostatin Microanatomy of the striatum: cell types Projection neurons: MSN: medium spiny neuron (GABA) •striatonigral projecting – ‘direct pathway’ •striatopallidal projecting – ‘indirect pathway’ Interneurons: FS: fast-spiking interneuron (GABA) LTS: low-threshold spiking interneuron (GABA) LA: large aspiny neuron (ACh) 30 um Cellular properties of striatal neurons Microanatomy of the striatum: striatal microcircuits • Feedforward inhibition (mediated by fast-spiking interneurons) • Lateral feedback inhibition (mediated by MSN collaterals) Basal Ganglia Circuits: The ‘Classical’ Model of Direct and Indirect Pathway Function Motor Cortex Premotor Cortex + Glutamate Striatum GPe GPi/SNr Dopamine + - GABA - Motor Thalamus SNc STN The simplified ‘classical’ model of basal ganglia circuit function • Information encoded as firing rate • Basal ganglia circuit is linear and unidirectional • Dopamine exerts opposing effects on direct and indirect pathway MSNs Basal ganglia motor circuit: direct pathway Motor Cortex Premotor Cortex Glutamate Striatum GPe GPi/SNr Dopamine + GABA Motor Thalamus SNc STN Direct pathway MSNs express: D1, M4 receptors, Sub. -

Midbrain Dopaminergic and Gabaergic Neurons' Responses To

Institute of Zoology and Biomedical Research Topic: Midbrain dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons' responses to the aversive stimulus across alternating brain states of urethane anaesthetized rat - electrophysiological in vivo studies. Supervisor: dr hab. Tomasz Błasiak (Department of Neurophysiology and Chronobiology) [email protected] Background information: Ventral tegmental area (VTA) is one of the main sources of dopamine (DA) in the mammalian brain. This structure is the centre of dopaminergic pathways and plays a key role in regulation of motivation (Wise, 2005), goaldirected behaviours, reinforcement learning or reacting to reward-related cues (Schultz, 1997; Morita, 2013). Better understanding of how DA circuits work and are modulated can contribute to explanation of mechanisms of dysfunctions laying at the root of some nervous system disorders such as addiction, anxiety, PTSD or some of depression symptoms (anhedonia or lack of motivation). It has been shown that, occurrence of unexpected reward, reward-related cue or novelty causes phasic release of DA in VTA target structures (Goto et al, 2007). Those phasic changes in DA neurons activity lie at the root of forming reward prediction error (RPE) signal which encodes difference between expected and delivered reward - updating reward expectations and forming the basis for learning (Schultz, 2016). DA neurons also code response to the aversive or noxious stimuli by development of quick, short latency pause in firing. For a long time, it has been assumed that DA neurons code both reward and aversive stimuli homogenously across the entire dopaminergic neurons population forming positive and negative prediction error signals respectively (Schultz, 1998; Ungless et al., 2004). -

Gene Expression of Prohormone and Proprotein Convertases in the Rat CNS: a Comparative in Situ Hybridization Analysis

The Journal of Neuroscience, March 1993. 73(3): 1258-1279 Gene Expression of Prohormone and Proprotein Convertases in the Rat CNS: A Comparative in situ Hybridization Analysis Martin K.-H. Schafer,i-a Robert Day,* William E. Cullinan,’ Michel Chri?tien,3 Nabil G. Seidah,* and Stanley J. Watson’ ‘Mental Health Research Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-0720 and J. A. DeSeve Laboratory of *Biochemical and 3Molecular Neuroendocrinology, Clinical Research Institute of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2W lR7 Posttranslational processing of proproteins and prohor- The participation of neuropeptides in the modulation of a va- mones is an essential step in the formation of bioactive riety of CNS functions is well established. Many neuropeptides peptides, which is of particular importance in the nervous are synthesized as inactive precursor proteins, which undergo system. Following a long search for the enzymes responsible an enzymatic cascade of posttranslational processing and mod- for protein precursor cleavage, a family of Kexin/subtilisin- ification events during their intracellular transport before the like convertases known as PCl, PC2, and furin have recently final bioactive products are secreted and act at either pre- or been characterized in mammalian species. Their presence postsynaptic receptors. Initial endoproteolytic cleavage occurs in endocrine and neuroendocrine tissues has been dem- C-terminal to pairs of basic amino acids such as lysine-arginine onstrated. This study examines the mRNA distribution of (Docherty and Steiner, 1982) and is followed by the removal these convertases in the rat CNS and compares their ex- of the basic residues by exopeptidases. Further modifications pression with the previously characterized processing en- can occur in the form of N-terminal acetylation or C-terminal zymes carboxypeptidase E (CPE) and peptidylglycine a-am- amidation, which is essential for the bioactivity of many neu- idating monooxygenase (PAM) using in situ hybridization ropeptides. -

The Brain Stem Medulla Oblongata

Chapter 14 The Brain Stem Medulla Oblongata Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Central sulcus Parietal lobe • embryonic myelencephalon becomes Cingulate gyrus leaves medulla oblongata Corpus callosum Parieto–occipital sulcus Frontal lobe Occipital lobe • begins at foramen magnum of the skull Thalamus Habenula Anterior Epithalamus commissure Pineal gland • extends for about 3 cm rostrally and ends Hypothalamus Posterior commissure at a groove between the medulla and Optic chiasm Mammillary body pons Cerebral aqueduct Pituitary gland Fourth ventricle Temporal lobe • slightly wider than spinal cord Cerebellum Midbrain • pyramids – pair of external ridges on Pons Medulla anterior surface oblongata – resembles side-by-side baseball bats (a) • olive – a prominent bulge lateral to each pyramid • posteriorly, gracile and cuneate fasciculi of the spinal cord continue as two pair of ridges on the medulla • all nerve fibers connecting the brain to the spinal cord pass through the medulla • four pairs of cranial nerves begin or end in medulla - IX, X, XI, XII Medulla Oblongata Associated Functions • cardiac center – adjusts rate and force of heart • vasomotor center – adjusts blood vessel diameter • respiratory centers – control rate and depth of breathing • reflex centers – for coughing, sneezing, gagging, swallowing, vomiting, salivation, sweating, movements of tongue and head Medulla Oblongata Nucleus of hypoglossal nerve Fourth ventricle Gracile nucleus Nucleus of Cuneate nucleus vagus -

Distinct Transcriptomic Cell Types and Neural Circuits of the Subiculum and Prosubiculum Along 2 the Dorsal-Ventral Axis 3 4 Song-Lin Ding1,2,*, Zizhen Yao1, Karla E

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.14.876516; this version posted December 15, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Distinct transcriptomic cell types and neural circuits of the subiculum and prosubiculum along 2 the dorsal-ventral axis 3 4 Song-Lin Ding1,2,*, Zizhen Yao1, Karla E. Hirokawa1, Thuc Nghi Nguyen1, Lucas T. Graybuck1, Olivia 5 Fong1, Phillip Bohn1, Kiet Ngo1, Kimberly A. Smith1, Christof Koch1, John W. Phillips1, Ed S. Lein1, 6 Julie A. Harris1, Bosiljka Tasic1, Hongkui Zeng1 7 8 1Allen Institute for Brain Science, Seattle, WA 98109, USA 9 10 2Lead Contact 11 12 *Correspondence: [email protected] (SLD) 13 14 15 Highlights 16 17 1. 27 transcriptomic cell types identified in and spatially registered to “subicular” regions. 18 2. Anatomic borders of “subicular” regions reliably determined along dorsal-ventral axis. 19 3. Distinct cell types and circuits of full-length subiculum (Sub) and prosubiculum (PS). 20 4. Brain-wide cell-type specific projections of Sub and PS revealed with specific Cre-lines. 21 22 23 In Brief 24 25 Ding et al. show that mouse subiculum and prosubiculum are two distinct regions with differential 26 transcriptomic cell types, subtypes, neural circuits and functional correlation. The former has obvious 27 topographic projections to its main targets while the latter exhibits widespread projections to many 28 subcortical regions associated with reward, emotion, stress and motivation.