The Potential for Laurel Wilt to Threaten Avocado Production Is Real

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

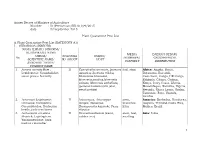

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Xyleborus Bispinatus Reared on Artificial Media in the Presence Or

insects Article Xyleborus bispinatus Reared on Artificial Media in the Presence or Absence of the Laurel Wilt Pathogen (Raffaelea lauricola) Octavio Menocal 1,*, Luisa F. Cruz 1, Paul E. Kendra 2 ID , Jonathan H. Crane 1, Miriam F. Cooperband 3, Randy C. Ploetz 1 and Daniel Carrillo 1 1 Tropical Research & Education Center, University of Florida 18905 SW 280th St, Homestead, FL 33031, USA; luisafcruz@ufl.edu (L.F.C.); jhcr@ufl.edu (J.H.C.); kelly12@ufl.edu (R.C.P.); dancar@ufl.edu (D.C.) 2 Subtropical Horticulture Research Station, USDA-ARS, 13601 Old Cutler Rd., Miami, FL 33158, USA; [email protected] 3 Otis Laboratory, USDA-APHIS-PPQ-CPHST, 1398 W. Truck Road, Buzzards Bay, MA 02542, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: omenocal18@ufl.edu; Tel.: +1-786-217-9284 Received: 12 January 2018; Accepted: 24 February 2018; Published: 28 February 2018 Abstract: Like other members of the tribe Xyleborini, Xyleborus bispinatus Eichhoff can cause economic damage in the Neotropics. X. bispinatus has been found to acquire the laurel wilt pathogen Raffaelea lauricola (T. C. Harr., Fraedrich & Aghayeva) when breeding in a host affected by the pathogen. Its role as a potential vector of R. lauricola is under investigation. The main objective of this study was to evaluate three artificial media, containing sawdust of avocado (Persea americana Mill.) and silkbay (Persea humilis Nash.), for rearing X. bispinatus under laboratory conditions. In addition, the media were inoculated with R. lauricola to evaluate its effect on the biology of X. bispinatus. There was a significant interaction between sawdust species and R. -

MYCOTAXON Volume 104, Pp

MYCOTAXON Volume 104, pp. 399–404 April–June 2008 Raffaelea lauricola, a new ambrosia beetle symbiont and pathogen on the Lauraceae T. C. Harrington1*, S. W. Fraedrich2 & D. N. Aghayeva3 *[email protected] 1Department of Plant Pathology, Iowa State University 351 Bessey Hall, Ames, IA 50011, USA 2Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service Athens, GA 30602, USA 3Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Patamdar 40, Baku AZ1073, Azerbaijan Abstract — An undescribed species of Raffaelea earlier was shown to be the cause of a vascular wilt disease known as laurel wilt, a severe disease on redbay (Persea borbonia) and other members of the Lauraceae in the Atlantic coastal plains of the southeastern USA. The pathogen is likely native to Asia and probably was introduced to the USA in the mycangia of the exotic redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus. Analyses of rDNA sequences indicate that the pathogen is most closely related to other ambrosia beetle symbionts in the monophyletic genus Raffaelea in the Ophiostomatales. The asexual genus Raffaelea includes Ophiostoma-like symbionts of xylem-feeding ambrosia beetles, and the laurel wilt pathogen is named R. lauricola sp. nov. Key words — Ambrosiella, Coleoptera, Scolytidae Introduction A new vascular wilt pathogen has caused substantial mortality of redbay [Persea borbonia (L.) Spreng.] and other members of the Lauraceae in the coastal plains of South Carolina, Georgia, and northeastern Florida since 2003 (Fraedrich et al. 2008). The fungus apparently was introduced to the Savannah, Georgia, area on solid wood packing material along with the exotic redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus Eichhoff (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), a native of southern Asia (Fraedrich et al. -

Phosphorous Application Improves Drought Tolerance of Phoebe Zhennan

fpls-08-01561 September 11, 2017 Time: 14:19 # 1 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by El Servicio de Difusión de la Creación Intelectual ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 13 September 2017 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01561 Phosphorous Application Improves Drought Tolerance of Phoebe zhennan Akash Tariq1,2, Kaiwen Pan1*, Olusanya A. Olatunji1,2, Corina Graciano3, Zilong Li1, Feng Sun1, Xiaoming Sun1, Dagang Song1, Wenkai Chen1, Aiping Zhang1, Xiaogang Wu1, Lin Zhang1, Deng Mingrui1, Qinli Xiong1 and Chenggang Liu1,4 1 CAS Key Laboratory of Mountain Ecological Restoration and Bioresource Utilization and Ecological Restoration Biodiversity Conservation Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China, 2 International College, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 3 Instituto de Fisiología Vegetal, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas – Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 4 Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China Phoebe zhennan (Gold Phoebe) is a threatened tree species in China and a valuable and important source of wood and bioactive compounds used in medicine. Apart from Edited by: anthropogenic disturbances, several biotic constraints currently restrict its growth and Urs Feller, development. However, little attention has been given to building adaptive strategies -

Arboretum News Armstrong News & Featured Publications

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Arboretum News Armstrong News & Featured Publications Spring 2019 Arboretum News Georgia Southern University- Armstrong Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/armstrong-arbor-news Part of the Education Commons This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Armstrong News & Featured Publications at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arboretum News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arboretum News Issue 9 | Spring 2019 A Newsletter of the Georgia Southern University Armstrong Campus Arboretum From the Editor: Arboretum News, published by the Grounds Operations Department ’d like to introduce you to the Armstrong Arboretum of the new of Georgia Southern University- IGeorgia Southern University-Armstrong Campus. Designated Armstrong Campus, is distributed as an on-campus arboretum in 2001 by former Armstrong to faculty, staff, students and Atlantic State University president Dr. Thomas Jones, the friends of the Armstrong Arboretum. The Arboretum university recognized the rich diversity of plant life on campus. encompasses Armstrong’s 268- The Arboretum continues to add to that diversity and strives to acre campus and displays a wide function as a repository for the preservation and the conservation variety of shrubs and other woody of plants from all over the world. We also hope to inspire students, plants. Developed areas of campus faculty, staff and visitors to appreciate the incredible diversity contain native and introduced species of trees and shrubs. Most that plants have to offer. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

Impacts of Laurel Wilt Disease on Native Persea of the Southeastern United States Timothy M

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2016 Impacts of Laurel Wilt Disease on Native Persea of the Southeastern United States Timothy M. Shearman Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Shearman, Timothy M., "Impacts of Laurel Wilt Disease on Native Persea of the Southeastern United States" (2016). All Dissertations. 1656. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1656 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMPACTS OF LAUREL WILT DISEASE ON NATIVE PERSEA OF THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Forest Resources by Timothy M. Shearman May 2016 Accepted by: Dr. G. Geoff Wang, Committee Chair Dr. Saara J. DeWalt Dr. Donald L. Hagan Dr. Julia L. Kerrigan Dr. William C. Bridges ABSTRACT Laurel Wilt Disease (LWD) has caused severe mortality in native Persea species of the southeastern United States since it was first detected in 2003. This study was designed to document the range-wide population impacts to LWD, as well as the patterns of mortality and regeneration in Persea ecosystems. I used Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data from the U.S. Forest Service to estimate Persea borbonia (red bay) populations from 2003 to 2011 to see if any decline could be observed since the introduction of LWD causal agents. -

Arboretum News Armstrong News & Featured Publications

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Arboretum News Armstrong News & Featured Publications Arboretum News Number 4, Winter 2006 Armstrong State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/armstrong-arbor- news Recommended Citation Armstrong State University, "Arboretum News" (2006). Arboretum News. 4. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/armstrong-arbor-news/4 This newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Armstrong News & Featured Publications at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arboretum News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arboretum News A Newsletter of the Armstrong Atlantic State University Arboretum Issue 4 Winter 2006 International Garden Dedication Arboretum News Issue 4, Winter 2005 ‘Watch Us Grow’ Arboretum News, published International Garden Dedicated by the Grounds Department of Armstrong Atlantic State University, is distributed to faculty, staff, students, and friends of the Arboretum. The Arboretum encompasses Armstrong’s 268-acre campus and displays a wide variety of shrubs and other woody plants. Developed areas of campus contain native and introduced species of trees and shrubs, the majority of which are labeled. Natural areas of campus contain plants typical in Georgia’s coastal broadleaf evergreen forests. Several plant collections are well established in the Arboretum including a Camellia Garden, a Conifer Garden, a Fern Garden, a Ginger Garden, an International Garden, a Primitive Garden, and a White The Asian Plaza in the International Garden Garden. The AASU Arboretum welcomes your support. If you would like to help us grow, please By Nancy Lawson Remler call the office of External Affairs at 912- 927- 5208. -

Ozone Induced Stomatal Regulations, MAPK and Phytohormone Signaling in Plants

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Ozone Induced Stomatal Regulations, MAPK and Phytohormone Signaling in Plants Md. Mahadi Hasan 1 , Md. Atikur Rahman 2 , Milan Skalicky 3 , Nadiyah M. Alabdallah 4, Muhammad Waseem 1, Mohammad Shah Jahan 5,6 , Golam Jalal Ahammed 7 , Mohamed M. El-Mogy 8 , Ahmed Abou El-Yazied 9 , Mohamed F. M. Ibrahim 10 and Xiang-Wen Fang 1,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Grassland Agro-Ecosystems, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] (M.M.H.); [email protected] (M.W.) 2 Grassland and Forage Division, National Institute of Animal Science, Rural Development Administration, Cheonan 31000, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Botany and Plant Physiology, Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, 16500 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] 4 Department of Biology, College of Science, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 383, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 5 Key Laboratory of Southern Vegetable Crop Genetic Improvement in Ministry of Agriculture, College of Horticulture, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing 210095, China; [email protected] 6 Department of Horticulture, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh 7 College of Horticulture and Plant Protection, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang 471023, China; [email protected] 8 Vegetable Crop Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt; Citation: Hasan, M.M.; Rahman, [email protected] 9 M.A.; Skalicky, M.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University, Cairo 11566, Egypt; Waseem, M.; Jahan, M.S.; Ahammed, [email protected] 10 Department of Agricultural Botany, Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University, Cairo 11566, Egypt; G.J.; El-Mogy, M.M.; El-Yazied, A.A.; [email protected] Ibrahim, M.F.M.; et al. -

The Newsletter of the IRISH GARDEN PLANT SOCIETY

The Newsletter of the IRISH GARDEN PLANT SOCIETY ISSUE NO. 95 JANUARY 2005 EDITORIAL “Isn’t it lovely to see the stretch in the evenings?” Have you, like me, heard this said again and again over the past while? And, one cannot but agree that it is indeed lovely to see the stretch in the evenings. This is a time of year with promise of better times to come. The dark days of winter are on the retreat and there are signs of new growth in the garden. This year’s weather conditions provided perfect conditions for excellent photographs of the winter solstice at Newgrange and that event marks the turn of the year and bring that much appreciated stretch in the evenings. May I wish all members a very Happy New Year, every success and enjoyment with your gardening during the coming year and I do hope you will come to the IGPS organised events during this coming year. But, most of all do make a New Year’s resolution to write a nice article for the newsletter! Paddy Tobin, “Cois Abhann”, Riverside, Lower Gracedieu, Waterford. Telephone: 051-857955 E-mail: [email protected] In this Issue Page 3: The Glasnevin China Expedition 2004: An account by Seamus of Brien of the trip to China last September. Page 11: The Glasnevin China Expedition 2004: A Note from Emer OReilly who accompanied Seamus. Page 12: Win Some, Lose…a lot: Rae McIntyre on the trials of being a gardener. Page 15: A Wee Bit of Plain Planting: Stephen Butler on gardening in the Zoo Page 16: Seed Distribution 2005: Stephen Butler with an update Page 17: The National Council for the Conservation of Plants and Gardens (NCCPG): a note from Stephen Butler. -

1 Recovery Plan for Laurel Wilt on Redbay and Other

Recovery Plan for Laurel Wilt on Redbay and Other Forest Species Caused by Raffaelea lauricola and disseminated by Xyleborus glabratus Updated January 2015 (Replaces December 2009 Version) Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………….………………………………………………..…………………………………………….. 2 Contributors and Reviewers…………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………. 4 I. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 5 II. Disease Cycle and Symptom Development….……………………………………………………………………………….……. 9 III. Spread……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……….…… 23 IV. Monitoring and Detection………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 25 V. Response…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 29 VI. Permits and Regulatory Issues…………………………………………………..……………………………………………………. 32 VII. Cultural, Economic and Ecological Impacts……………..…………………………………………………………………….. 33 VIII. Mitigation and Disease Management…………………………………………………………………………………………... 38 IX. Infrastructure and Experts……………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 45 X. Research, Extension, and Education Needs….……………………………………………………………………………….... 48 XI. References……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 50 XII. Web Resources…………………………………………………...……………………………………………………………………..…. 58 This recovery plan is one of several disease-specific documents produced as part of the National Plant Disease Recovery System (NPDRS) called for in Homeland Security Presidential Directive Number 9 (HSPD-9). The purpose of the NPDRS is to insure that the tools, infrastructure, communication -

Fungi of Raffaelea Genus (Ascomycota: Ophiostomatales) Associated to Platypus Cylindrus (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) in Portugal

FUNGI OF RAFFAELEA GENUS (ASCOMYCOTA: OPHiostomATALES) ASSOCIATED to PLATYPUS CYLINDRUS (COLEOPTERA: PLATYPODIDAE) IN PORTUGAL FUNGOS DO GÉNERO RAFFAELEA (ASCOMYCOTA: OPHiostomATALES) ASSOCIADOS A PLATYPUS CYLINDRUS (COLEOPTERA: PLATYPODIDAE) EM PORTUGAL MARIA LURDES INÁCIO1, JOANA HENRIQUES1, ARLINDO LIMA2, EDMUNDO SOUSA1 ABSTRACT Key-words: Ambrosia beetle, ambrosia fun- gi, cork oak, decline. In the study of the fungi associated to Platypus cylindrus, several fungi were isolated from the insect and its galleries in cork oak, RESUMO among which three species of Raffaelea. Mor- phological and cultural characteristics, sensitiv- No estudo dos fungos associados ao insec- ity to cycloheximide and genetic variability had to xilomicetófago Platypus cylindrus foram been evaluated in a set of isolates of this genus. isolados, a partir do insecto e das suas ga- On this basis R. ambrosiae and R. montetyi were lerias no sobreiro, diversos fungos, entre os identified and a third taxon segregated witch quais três espécies de Raffaelea. Avaliaram-se differs in morphological and molecular charac- características morfológicas e culturais, sensibi- teristics from the previous ones. In this work we lidade à ciclohexamida e variabilidade genética present and discuss the parameters that allow num conjunto de isolados do género. Foram the identification of specimens of the threetaxa . identificados R. ambrosiae e R. montetyi e The role that those ambrosia fungi can have in segregou-se um terceiro táxone que difere the cork oak decline is also discussed taking em características morfológicas e molecula- into account that Ophiostomatales fungi are res dos dois anteriores. No presente trabalho pathogens of great importance in trees, namely são apresentados e discutidos os parâmetros in species of the genus Quercus.