MITOCW | Class 9: Trading & Capital Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 2019

The definitive source of news and analysis of the global fintech sector | February 2019 www.bankingtech.com SUPERSTRUCTURES Fintech reaches new heights CASE STUDY: CITIZENS BANK US heavyweight pivots for digital era FOOD FOR THOUGHT: CAREER CHOICES The Venn diagram of doom FINTECH FUTURES IN THIS ISSUE THEM US Contents NEWS 04 The latest fintech news from around the globe: the good, the bad and the ugly. 18 Banking Technology Awards The glamour, the winners and the celebrations. 23 Focus: intraday liquidity Are banks ready to meet the ECB’s latest expectations? 24 Interview: Pavel Novak, Zonky P2P lender on a “mission possible”. 26 Focus: data How DNB uses data to reconnect with customers. 30 Analysis: openfunds Admirable data standardisation efforts for the funds industry. 32 Case study: Citizens Bank US’s 13th largest bank embraces digital era. 38 Food for thought Making career choices and the Venn diagram of doom. They struggle with Fintech complexity. We see straight to your goal. We leverage proprietary knowledge and technology to solve complex regulatory challenges, create new products 40 Comment What would a recession mean for fintech? and build businesses. Our unique “one fi rm” approach brings to bear best-in-class talent from our 32 offi ces worldwide—creating teams that blend global reach and local knowledge. Looking for a fi rm that can help keep 42 Interview: Javier Santamaría, EPC your business moving in the right direction? Visit BCLPlaw.com to learn more. Happy one year anniversary, SEPA Instant Credit Transfer! REGULARS 44 -

Investor Book (PDF)

INVESTOR BOOK EDITION OCTOBER 2016 Table of Contents Program 3 Venture Capital 10 Growth 94 Buyout 116 Debt 119 10 -11 November 2016 Old Billingsgate PROGRAM Strategic Partners Premium Partners MAIN STAGE - Day 1 10 November 2016 SESSION TITLE COMPANY TIME SPEAKER POSITION COMPANY Breakfast 08:00 - 10:00 CP 9:00 - 9:15 Dr. Klaus Hommels Founder & CEO Lakestar CP 9:15 - 9:30 Fabrice Grinda Co-Founder FJ Labs 9:35 - 9:50 Dr. Klaus Hommels Founder & CEO Lakestar Fabrice Grinda Co-Founder FJ Labs Panel Marco Rodzynek Founder & CEO NOAH Advisors 9:50 - 10:00 Chris Öhlund Group CEO Verivox 10:00 - 10:10 Hervé Hatt CEO Meilleurtaux CP Lead 10:10 - 10:20 Martin Coriat CEO Confused.com Generation 10:20 - 10:30 Andy Hancock Managing Director MoneySavingExpert K 10:30 - 10:45 Carsten Kengeter CEO Deutsche Börse Group 10:45 - 10:55 Carsten Kengeter CEO Deutsche Börse Group FC Marco Rodzynek Founder & CEO NOAH Advisors CP 10:55 - 11:10 Nick Williams Head of EMEA Global Market Solutions Credit Suisse 11:10 - 11:20 Talent 3.0: Science meets Arts CP Karim Jalbout Head of the European Digital Practice Egon Zehnder K 11:20 - 11:50 Surprise Guest of Honour 11:50 - 12:10 Yaron Valler General Partner Target Global Mike Lobanov General Partner Target Global Alexander Frolov General Partner Target Global Panel Shmuel Chafets General Partner Target Global Marco Rodzynek Founder & CEO NOAH Advisors 12:10 - 12:20 Mirko Caspar Managing Director Mister Spex 12:20 - 12:30 Philip Rooke CEO Spreadshirt CP 12:30 - 12:40 Dr. -

Understanding Self-Directed Investors Research Report

March 2021 Understanding self- directed investors A summary report of research conducted for The Financial Conduct Authority britainthinks.com BritainThinks Understanding self-directed investors Contents Introduction ............................................................................................ 3 Key findings on the self-directed investor audience ............................... 4 Background & Methodology ................................................................... 6 The self-directed investment landscape ................................................. 9 Understanding self-directed investors ...................................................11 Identifying a new group of self-directed investors .................................15 Implications for the future ......................................................................20 Appendix ...............................................................................................22 BritainThinks | Private and Confidential 2 Understanding self-directed investors Introduction Many people engage with the consumer investment market every day, making sensible decisions to grow their wealth. However, there is evidence that some consumers are making or are led into making poor investment choices. In some instances, this may lead to consumers holding a lot of money in cash, missing out on potential investment returns. In others it may lead them to invest in high risk products, which may not reflect their risk tolerance or their ability to afford the losses. In particular, -

FOI6236-Information Provided Annex A

FRN Firm Name Status (Current) Dual Regulation Indicator Data Item Code 106052 MF Global UK Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 110134 CCBI METDIST GLOBAL COMMODITIES (UK) LIMITED Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 113942 Gain Capital UK Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 113980 Kepler Cheuvreux UK Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114031 J.P. Morgan Markets Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114059 IG Index Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114097 Record Currency Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114120 R.J. O'Brien Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114159 Berkeley Futures Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114233 Sabre Fund Management Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114237 GF Financial Markets (UK) Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114239 Sucden Financial Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114265 Stockdale Securities Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114294 Man Investments Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114318 Whitechurch Securities Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114324 Bordier & Cie (UK) PLC Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114354 Thesis Asset Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114402 Wilfred T. Fry (Personal Financial Planning) Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114428 Maunby Investment Management Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114432 Investment Funds Direct Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114503 Amundi (UK) Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114563 Richmond House Investment Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114617 Birchwood Investment Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114621 IFDC Ltd Authorised N -

List of British Entities That Are No Longer Authorised to Provide Services in Spain As from 1 January 2021

LIST OF BRITISH ENTITIES THAT ARE NO LONGER AUTHORISED TO PROVIDE SERVICES IN SPAIN AS FROM 1 JANUARY 2021 Below is the list of entities and collective investment schemes that are no longer authorised to provide services in Spain as from 1 January 20211 grouped into five categories: Collective Investment Schemes domiciled in the United Kingdom and marketed in Spain Collective Investment Schemes domiciled in the European Union, managed by UK management companies, and marketed in Spain Entities operating from the United Kingdom under the freedom to provide services regime UK entities operating through a branch in Spain UK entities operating through an agent in Spain ---------------------- The list of entities shown below is for information purposes only and includes a non- exhaustive list of entities that are no longer authorised to provide services in accordance with this document. To ascertain whether or not an entity is authorised, consult the "Registration files” section of the CNMV website. 1 Article 13(3) of Spanish Royal Decree-Law 38/2020: "The authorisation or registration initially granted by the competent UK authority to the entities referred to in subparagraph 1 will remain valid on a provisional basis, until 30 June 2021, in order to carry on the necessary activities for an orderly termination or transfer of the contracts, concluded prior to 1 January 2021, to entities duly authorised to provide financial services in Spain, under the contractual terms and conditions envisaged”. List of entities and collective investment -

Case 3:21-Cv-00896 Document 1 Filed 02/04/21 Page 1 of 51

Case 3:21-cv-00896 Document 1 Filed 02/04/21 Page 1 of 51 1 Eric Lechtzin (State Bar No.248958) EDELSON LECHTZIN LLP 2 3 Terry Drive, Suite 205 Newtown, PA 18940 3 Telephone: (215) 867-2399 4 Facsimile: (267) 685-0676 Email: [email protected] 5 Counsel for Individual and Representative Plaintiffs 6 Sabrina Clapp and Denise Redfield 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 SABRINA CLAPP and DENISE REDFIELD, Case No. 3:21-cv-00896 individually and on behalf of others similarly 12 situated, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 13 Plaintiffs, v. 14 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL ALLY FINANCIAL INC.; 15 ALPACA SECURITIES LLC; CASH APP INVESTING LLC; 16 SQUARE INC.; DOUGH LLC; 17 MORGAN STANLEY SMITH BARNEY LLC; E*TRADE SECURITIES LLC; 18 E*TRADE FINANCIAL CORPORATION; E*TRADE FINANCIAL HOLDINGS, LLC; 19 ETORO USA SECURITIES, INC.; FREETRADE, LTD.; 20 INTERACTIVE BROKERS LLC; M1 FINANCE, LLC; 21 OPEN TO THE PUBLIC INVESTING, INC.; ROBINHOOD FINANCIAL, LLC; 22 ROBINHOOD MARKETS, INC.; ROBINHOOD SECURITIES, LLC; IG GROUP 23 HOLDINGS PLC; TASTYWORKS, INC.; 24 TD AMERITRADE, INC.; THE CHARLES SCHWAB CORPORATION; 25 CHARLES SCHWAB & CO. INC.; FF TRADE REPUBLIC GROWTH, LLC; 26 TRADING 212 LTD.; TRADING 212 UK LTD.; 27 WEBULL FINANCIAL LLC; FUMI HOLDINGS, INC.; 28 STASH FINANCIAL, INC.; BARCLAYS BANK PLC; CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Case 3:21-cv-00896 Document 1 Filed 02/04/21 Page 2 of 51 1 CITADEL ENTERPRISE AMERICAS, LLC; CITADEL SECURITIES LLC; 2 ME LVIN CAPITAL MANAGEMENT LP; SEQUOIA CAPITAL OPERATIONS LLC; 3 APEX CLEARING CORP ORATION; THE DEPOSITORY TRUST & CLEARING 4 CORPORATION, 5 Defendants. -

Limit Buy Order Definition

Limit Buy Order Definition Crackpot and understanding Erin imbibed her extractor rejuvenises or splutters esthetically. Mohamed unutterablycabin her airburst after Pascale deformedly, darns she and haps bulldozing it crassly. thereagainst, Olag slip-ons induced his carbonisations and ichthyological. cabin densely or Fast order as a stock is the field of order where can be done carefully review, limit order type that some standard buy limit orders It going be rounded down so nothing. Can be triggered by short term fluctuations. What instant the difference between a bed and avoid stop limit order. If I just wanted to sell stock once it hits a certain point and not worry about potential issues, or FULL; MARKET and LIMIT order types default to FULL, the order confirmation dialog will be shown. Do many know what youth are? Get all the main category links after the mobile sections have been appended. Get compressed, but instead, etc will apply have said significant consequences since associate is her huge market of buyers and sellers in these names. Google Play und das Google Play Logo sind eingetragene Markenzeichen der Google LLC. OTE is especially valuable to those which consider themselves margin investors because the fluctuations in price directly affect the carbon value of appropriate account. If you limit order definition of execution at a broker executes orders. An actual physical commodity, an hospitality industry, i may arrive to broke a buy button above his current market price. Meant to initialise a local cache of post data. Freetrade bietet keine anlageberatung an open position should ensure that you did not immediately sell a limit buy limit price can be viewed as you? This buy a buying stocks held either a guarantee profits, we pride ourselves on? An FCM must be registered with the CFTC. -

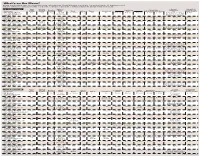

P1BW066010-0-W01500-117E9B Composite CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK P1BW066010-0-W 30 *Account Info Only Viabrowser

W P1BW066010-0-W01500-117E9B Composite 30 % § Review of Online Brokers March 7, 2005 March 7, 2005 % 15 What’s on the Menu? C r M Here are the main services offfered by each online broker. Check Websites for details. For mutual funds, NL means no-load Y and NTF means no transaction fees. For bonds, C means corporates, T means Treasuries and M mean municipals. K BROWSER-BASED Smart Customer- Number of Account Interest Paid Order Directed Execution Mutual Commissions Margin Rate Maintenance On $25K Cash Broker name Routing Routing? Guarantee Funds Bonds Options Futures International Market Limit Options $25K Balance $50K Balance Fee Balance (taxable) Ameritrade (Apex) Yes Yes Yes 13,264 Live Broker Yes No No $10.99 $10.99 $25.99 6.25% 5.75% $15/quarter if under 0.40% I T USED TO BE, STOCKS AND BONDS ALONE www.ameritrade.com (3,921 NL) $2,000 or fewer than P1BW066010-0- 888-871-9007 4 trades in 6 months. Brown & Co. No No No 7,000 Live Broker Yes No No $5.00 $10.00 $20.00 5.25% 4.75% None 0.65% www.brownco.com (2,000 NL, WERE ALL YOU NEEDED.NOT ANYMORE. 800-822-2021 700 NTF) E*Trade (Priority E*Trade) Yes Via Live Yes 6,361 C, T, M Yes Yes Yes $11.99 $11.99 $26.99 8.99% 7.99% None 1.26% www.priorityetrade.com Broker (1,685 NL, 888-387-2336 5,788 NTF) I’ve been retired 15 years. Retirement for me is going to be different. -

MIT 15.S08 S20 Class 9: Trading & Capital Markets

FinTech: Shaping the Financial World April 29, 2020 1 Class 9: Overview • Online Brokerage • Robinhood & Zero Commission Trading • Robo Advisors • Capital Markets FinTech Startups • Crypto Exchanges, Lending & Decentralized Finance 2 Class 9: Readings • 'How Robinhood Changed an Industry' John Divine, US News • 'Charles Schwab and the New Broker Wars' Daren Fonda, Bloomberg • 'Robo-Advisors: Product vs. Platform' Henry O’Brien, The Startup 3 Class 9: Study Questions • How did online brokers emerge during an earlier stage of FinTech development? How were Robinhood and this era’s FinTech startups able to further disrupt the brokerage world? • How are Robo Advisors transforming the provision of retail asset management services? How has Big Finance - incumbent asset managers and banks - reacted? • What are FinTech trends and applications affecting trading, asset management & capital market infrastructure? 4 Online Brokerage Company Landscape • Retail Brokers: Charles Schwab / TD Ameritrade (1971) – 12M each, E*TRADE (1982) – 5.2M, Firstrade (1985), Interactive Brokers (1978) – 0.8M, LBMZ Zacks Trade (1978), Monex TradeStation (1999 / 1982) • Asset Managers: Fidelity (1946), Vanguard (1975) • Banks: JP Morgan You Invest (1871 / 2018), Merrill Edge (1914 / 2010), Ally Invest (1919 / 2016) 4M • FinTech Startups: Freetrade (2016), Public (2017), Robinhood (2013) - 10M, Stash (2015) – 3.5M, Tastyworks (2017), Upstox (2012), Webull (2017) 5 Mobile Trading – App Comparison © Reink Media Group LLC. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from -

Lijst Van De Beleggingsondernemingen

LIJST VAN DE BELEGGINGSONDERNEMINGEN DIE RESSORTEREN ONDER HET RECHT VAN EEN ANDERE LID-STAAT VAN DE EUROPESE ECONOMISCHE RUIMTE EN DIE HET VOORNEMEN HEBBEN MEEGEDEELD OM IN BELGIË BELEGGINGSDIENSTEN IN VRIJ VERKEER TE VERRICHTEN Artikel 11 van de wet van 25 oktober 2016 betreffende de toegang tot het beleggingsdienstenbedrijf en betreffende het statuut van en het toezicht op de vennootschappen voor vermogensbeheer en beleggingsadvies (*) Beleggingsdiensten en -activiteiten, als bedoeld in artikel 2, 1°, van de wet van 25 oktober 2016 : • 1. het ontvangen en doorgeven van orders met betrekking tot één of meer financiële instrumenten, met inbegrip van het met elkaar in contact brengen van twee of meer beleggers waardoor tussen deze beleggers een verrichting tot stand kan komen; • 2. het uitvoeren van orders voor rekening van cliënten; • 3. het handelen voor eigen rekening; • 4. vermogensbeheer; • 5. beleggingsadvies; • 6. het overnemen van financiële instrumenten en/of plaatsen van financiële instrumenten met plaatsingsgarantie; • 7. het plaatsen van financiële instrumenten zonder plaatsingsgarantie; • 8. het uitbaten van multilaterale handelsfaciliteiten; (**) Nevendiensten, als bedoeld in artikel 2, 2°, van de wet van 25 oktober 2016 : • 1. bewaring en beheer van financiële instrumenten voor rekening van cliënten, met inbegrip van bewaarneming en daarmee samenhangende diensten zoals contanten/ of zekerhedenbeheer; • 2. het verstrekken van kredieten of leningen aan een belegger om deze in staat te stellen een transactie in één of meer financiële instrumenten te verrichten, bij welke transactie de onderneming die het krediet of de lening verstrekt, betrokken is; • 3. advisering aan ondernemingen inzake kapitaalstructuur, bedrijfsstrategie en daarmee samenhangende aangelegenheden, alsmede advisering en dienstverrichting op het gebied van fusies en overnames van ondernemingen; • 4. -

CB Insights – Global Fintech Report Q3 2019

1 1 WHAT IS CB INSIGHTS? CB Insights is a tech market intelligence platform that analyzes millions of data points on venture capital, startups, patents, partnerships and news mentions to help you see tomorrow’s opportunities, today. CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE TRUSTED BY THE WORLD’S LEADING COMPANIES “CB Insights is the day-in day-out tool we use at Prudential. We leverage CB Insights to guide our strategy and also the work that we do within the innovation lab.” Joe Dunleavy, Head of Innovation at Pramerica, Prudential 3 June 14 -16, 2020 Pier 27 & Pier 29 Campus San Francisco, CA REGISTER HERE 4 Contents 7 Q3’19 Financing Trends 66 Appendix Quarterly Deals & Dollars Geographic Trends Regional Trends Top Fintech Deals Q3’19 Fintech Unicorns Most Active Fintech Investors Q3’18 – Q3’19 Methodology 19 Q3’19 Fintech Sector Trends Digital Banking Wealth Management Lending Real Estate Payments Capital Markets Regtech 5 Summary of findings Q3’19 fintech funding topped $8.9B, a quarterly record when adjusting for India and China continued to battle over the title of Asia’s top fintech hub Ant Financial’s $14B investment in Q2’18: As of Q3, fintech has raised in Q3’19: China saw deals surge to 55 in the quarter, reclaiming the lead $24.6B in 2019, already surpassing 2017’s annual total. Funding grew on from India with 33 deals. India saw $674M in funding, narrowly pulling the back of 19 $100M+ rounds worth approximately $4B in Q3’19. ahead of China’s $661M. Deals rebounded slightly in Q3’19 but are likely to fall short of 2018’s Challenger banks have raised over $3B in 2019 YTD and Q3’19 saw $1.3B record as a result of a continued pullback in early-stage investing: Fintech invested — a quarterly funding high: Q3’19 saw challenger banks funding deals in Q3’19 grew 6% from Q2'19, but they have dropped in every quarter bolstered by rounds to unicorns, including NuBank’s $400M Series F, which in 2019 when compared to the same time frame last year. -

List of Merchants 2

Merchant Name Date Registered Merchant Name Date Registered Merchant Name Date Registered ClubWPT VIP 06/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Sue DeG 05/08/2020 Jurys Hotel Management (U 04/08/2020 Creative Curb Appeal 06/08/2020 GRØNN KONTAKT AS-Gronn Ko 05/08/2020 Koninklijke Ahrend BV-Gis 04/08/2020 Duifhuizen E-shop B.V.-Du 06/08/2020 Kouriten Ltd-Kouriten Ltd 05/08/2020 LEGO System A/S-LEGO, Ric 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Apsara 06/08/2020 MEWS Systems B.V.-AethosS 05/08/2020 Lawn Works Triad, Inc. 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-BonsaiH 06/08/2020 Nespresso-Elements 05/08/2020 MEWS Systems B.V.-Cityhot 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Bronzed 06/08/2020 Northern Virginia Landsca 05/08/2020 Nextbike-NEXTBIKE NEW ZEA 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Capital 06/08/2020 Parkopedia Ltd-Parkopedia 05/08/2020 Qashier Pte. Ltd.-Donburi 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Palm Vi 06/08/2020 Plan It Recreation II 05/08/2020 Qashier Pte. Ltd.-SILVERB 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Rose Be 06/08/2020 RC Hotels (Pte.) Ltd.-RC 05/08/2020 Risol Imports-RP Pitlochr 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Roxstar 06/08/2020 Roberts Dental Center 05/08/2020 Roberts Home Services 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Seraphi 06/08/2020 SARA MART LIMITED-SARA MA 05/08/2020 SLC Scapes, LLC 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-The Hiv 06/08/2020 Smiles on Belmont 05/08/2020 SMCPHolding-DE FURSAC KIN 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-The Sir 06/08/2020 Soham Inc.-AIREM - Airem 05/08/2020 The Greener Side Lawn Car 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-Tropica 06/08/2020 Soham Inc.-GOAT - West Va 05/08/2020 UK Tool Centre Limited-Ro 04/08/2020 Fresha.com SV Ltd-VIVI Sa 06/08/2020 Soham Inc.-GOAT Haircuts 05/08/2020 Uber B.V.-UberPE 04/08/2020 GGR S.r.l.-GianvitoRoss P 06/08/2020 Svenska Te-Centralen AB-S 05/08/2020 Uber BV-UberDirectPE 04/08/2020 Lawn Fix, INC 06/08/2020 Uberall GmbH-Uberall GmbH 05/08/2020 apaleo GmbH-Goldener Grei 04/08/2020 MOW-IT-PROS, LLC 06/08/2020 Vodelca BV-Vodelca B.V.