Tuberculosis Mycobacterium Immune Response to Diabetic Mice Display

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lung Anatomy

Lung anatomy Breathing Breathing is an automatic and usually subconscious process which is controlled by the brain. The brain will determine how much oxygen we require and how fast we need to breathe in order to supply our vital organs (brain, heart, kidneys, liver, stomach and bowel), as well as our muscles and joints, with enough oxygen to carry out our normal daily activities. In order for breathing to be effective we need to use our lungs, breathing muscles and blood system efficiently. This leaflet should help you to better understand the process of breathing and how we get the much needed oxygen into our bodies. The lungs You have two lungs, one in the right side and one in the left side of your chest. The right lung is bigger than the left due to the position of the heart (which is positioned in the left side of the chest). Source: Pulmonary Rehabilitation Reference No: 66354-1 Issue date: 13/2/20 Review date: 13/2/23 Page 1 of 5 Both lungs are covered by 2 thin layers of tissue called the pleura. The pleura stop the surface of the lungs rubbing together as we breathe in and out. The lungs are protected by the ribcage. The airways Within the lungs there is a vast network of airways (tubes) which help to transport the oxygen into the lungs and the carbon dioxide out. These tubes branch into smaller and smaller tubes the further they go into the lungs. Page 2 of 5 Trachea (windpipe): This tube connects your nose and mouth to your lungs. -

Lung Microbiome Participation in Local Immune Response Regulation in Respiratory Diseases

microorganisms Review Lung Microbiome Participation in Local Immune Response Regulation in Respiratory Diseases Juan Alberto Lira-Lucio 1 , Ramcés Falfán-Valencia 1 , Alejandra Ramírez-Venegas 2, Ivette Buendía-Roldán 3 , Jorge Rojas-Serrano 4 , Mayra Mejía 4 and Gloria Pérez-Rubio 1,* 1 HLA Laboratory, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] (J.A.L.-L.); [email protected] (R.F.-V.) 2 Tobacco Smoking and COPD Research Department, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Translational Research Laboratory on Aging and Pulmonary Fibrosis, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] 4 Interstitial Lung Disease and Rheumatology Unit, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] (J.R.-S.); [email protected] (M.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-55-5487-1700 (ext. 5152) Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 16 July 2020 Abstract: The lung microbiome composition has critical implications in the regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. Next-generation sequencing techniques have revolutionized the understanding of pulmonary physiology and pathology. Currently, it is clear that the lung is not a sterile place; therefore, the investigation of the participation of the pulmonary microbiome in the presentation, severity, and prognosis of multiple pathologies, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and interstitial lung diseases, contributes to a better understanding of the pathophysiology. Dysregulation of microbiota components in the microbiome–host interaction is associated with multiple lung pathologies, severity, and prognosis, making microbiome study a useful tool for the identification of potential therapeutic strategies. -

Manatee Anatomy and Physiology

Manatee Anatomy and Physiology Grade level: Elementary 5 Subject Area: Biology, Anatomy and Physiology, Marine Biology Duration: Teach: 15 minutes, Activity: 20 minutes, Discussion: 20 minutes. Setting: Classroom Next Generation Sunshine State Standards: Reading: LAFS.5.RI Reading standards for Information text Cluster 3 LAFS.5.RI.3 Writing: LA.B.2.1, LA.B.1.2 Speaking and Listening: Cluster 2 LAFS.5.SL.Z Presentation of Knowledge and Ideas Science: Body of Knowledge Life Science: SC.5.L.14, SC.5.L.15, SC.5.L.17, Body of Knowledge Nature of Science Supporting Idea 1: SC.5.N.1 Practice of Science, Supporting Idea 2:SC.5.N.2 Characteristics of Scientific Knowledge Earth Systems and Patterns: 7SC.E.E.7 Statewide Science Assessment Prompt: How might humans help manatees survive? Objectives: Students will learn about manatee bodies and explain some anatomical and physiological differences between manatees, humans and other animals. Materials: Handouts of basic manatee anatomy, dolphin anatomy & human anatomy, crayons or markers, coloring direction sheet, question worksheet, Quiz sheet Vocabulary: Mammal, endangered species, habitat, conservation, vibrissae, nares, blowhole, flipper, herbivore, omnivore, carnivore. Background/Preparation: Handouts of manatee, dolphin, and human anatomy. Fact sheets comparing and contrasting specific and unique anatomical aspects of each species. Basic manatee fact sheet highlighting personality, limited habitat, endangered status and conservation efforts. Teachers can review the manatee fact sheets, and select points of interest they would most like to incorporate into a lesson. This activity may fit best into the week where the human anatomy lessons are addressed. Teachers can present the information via traditional lecture, group discussion, question and answer session, or doing the coloring activity as the lesson points are addressed, etc. -

The Fifth Pulmonary Vein

CASE REPORT Anatomy Journal of Africa. 2016. Vol 5 (2): 704 - 706 The Fifth Pulmonary vein Hilkiah Kinfemichael, Asrat Dawit Correspondence to Hilkiah Kinfemichael, Myungsung Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia PO Box 14972 Email : [email protected]. ABSTRACT A cadaver in Myungsung Medical College (MMC) had a 3rd pulmonary vein originating from the middle lobe of the right lung. Such anatomical variations are very rare. People with this variation have a total of five pulmonary veins entering left atrium. It has clinical implications especially for thoracic surgeons and radiologists during radiofrequency ablations, lobectomies, valve replacements, pulmonary vein catheterizations, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) and others. Key Words: Anatomy, Variations, Pulmonary veins. INTRODUCTION Two pulmonary veins usually drain oxygenated upper lobe, is formed by the union of blood from each lung to left atrium of the apicoposterior, anterior and lingular veins. The heart. The lobular tributaries lie mainly in the inferior left pulmonary vein, which drains the interlobular septa and two pulmonary veins lower lobe, is formed by the hilar union of two from each lung enter left atrium through two veins, superior and common basal veins. The separate pulmonary ostia on either side. On the right and left pulmonary veins perforate the right lung veins from the apical, anterior and fibrous pericardium and open separately in the posterior part of upper lobe unite with a middle posterosuperior aspect of the left atrium lobar vein, which is formed by lateral and (Standring et al., 2008). This anatomy could medial tributaries, and form the superior right show variations, with more veins draining pulmonary vein (Standring, 2008). -

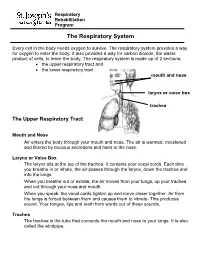

The Respiratory System

Respiratory Rehabilitation Program The Respiratory System Every cell in the body needs oxygen to survive. The respiratory system provides a way for oxygen to enter the body. It also provides a way for carbon dioxide, the waste product of cells, to leave the body. The respiratory system is made up of 2 sections: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract mouth and nose larynx or voice box trachea The Upper Respiratory Tract Mouth and Nose Air enters the body through your mouth and nose. The air is warmed, moistened and filtered by mucous secretions and hairs in the nose. Larynx or Voice Box The larynx sits at the top of the trachea. It contains your vocal cords. Each time you breathe in or inhale, the air passes through the larynx, down the trachea and into the lungs. When you breathe out or exhale, the air moves from your lungs, up your trachea and out through your nose and mouth. When you speak, the vocal cords tighten up and move closer together. Air from the lungs is forced between them and causes them to vibrate. This produces sound. Your tongue, lips and teeth form words out of these sounds. Trachea The trachea is the tube that connects the mouth and nose to your lungs. It is also called the windpipe. The Lower Respiratory Tract Inside Lungs Outside Lungs bronchial tubes alveoli diaphragm (muscle) Bronchial Tubes The trachea splits into 2 bronchial tubes in your lungs. These are called the left bronchus and right bronchus. The bronchus tubes keep branching off into smaller and smaller tubes called bronchi. -

Lung Lobe Segmentation Based on Lung Fissure Surface Classification

algorithms Article Lung Lobe Segmentation Based on Lung Fissure Surface Classification Using a Point Cloud Region Growing Approach Xin Chen 1, Hong Zhao 2 and Ping Zhou 3,* 1 College of Electrical and Information Engineering, Hunan University, Changsha 410082, China; [email protected] 2 College of Aerospace Science and Engineering, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha 410003, China; [email protected] 3 College of Biology, Hunan University, Changsha 410082, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 13 October 2020; Published: 15 October 2020 Abstract: In anatomy, the lung can be divided by lung fissures into several pulmonary lobe units with specific functions. Identifying the lung lobes and the distribution of various diseases among different lung lobes from CT images is important for disease diagnosis and tracking after recovery. In order to solve the problems of low tubular structure segmentation accuracy and long algorithm time in segmenting lung lobes based on lung anatomical structure information, we propose a segmentation algorithm based on lung fissure surface classification using a point cloud region growing approach. We cluster the pulmonary fissures, transformed into point cloud data, according to the differences in the pulmonary fissure surface normal vector and curvature estimated by principal component analysis. Then, a multistage spline surface fitting method is used to fill and expand the lung fissure surface to realize the lung lobe segmentation. The proposed approach was qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated on a public dataset from Lobe and Lung Analysis 2011 (LOLA11), and obtained an overall score of 0.84. Although our approach achieved a slightly lower overall score compared to the deep learning based methods (LobeNet_V2 and V-net), the inter-lobe boundaries from our approach were more accurate for the CT images with visible lung fissures. -

Clay Adams Anatomical Model

3D Educational Resources LEARN ABOUT THE HUMAN BODY! The human body is an amazing living machine. It contains complex organs that perform all sorts of functions that work together to keep us alive. Find out more about how they do this in a series of fun mini-activities and demonstrations. ONTARIO CURRICULUM LINKS Through this activity, you and your students will use an anatomical model to go through a series of mini-activities and demonstrations about our body’s organs. This activity can be connected to multiple aspects of the school curriculum, our suggested link is: Grade 5: Science (Human Organ Systems) MATERIALS Grades 1 measuring cup 1 3D printout of the anatomical 5 – 9 1 tablespoon (15 mL) model or 3D files of the anatomical 2 bowls (around 1 L model and each) software* to view the files Ag e Range 1 ruler 1.65 m yarn 8 – 14 years 1 measuring tape 900 mL water 750 mL vinegar * Note: There are many free programs available to view the 3D files. Some examples include Sketchup Make (https://www.sketchup.com/download/all) and 3D Builder, which is included with Windows 10. IngeniumCanada.org INSTRUCTIONS These activities can be done either with a 3D printed anatomical model or through viewing the 3D model with a computer program. Feel free to add your own contributions and explore parts of the model not covered in this document. Assembling the Anatomical Model If you are having trouble putting together the anatomical model, you can find below a series of diagrams that should help you out. -

Patient and Physician Guide: National Lung Screening Trial (NLST)

Patient and Physician Guide: National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) What is the purpose of this guide? To explain the benefits and harms of low-dose computed tomography (CT) screening for lung cancer in people at high risk for the disease. The NLST showed a reduction in deaths from CT screening compared to chest X-ray screening. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial recently showed that chest X-ray screening (compared to no screening) did NOT reduce the chance of dying from lung cancer. Who participated in the NLST? Current or former cigarette smokers within the past 15 years, 55 to 74 years of age, with at least 30 pack-years of smoking [Pack-years = packs per day x number of years smoking]. Participants must have had no symptoms or signs of lung cancer or other serious medical conditions, and be medically fit for surgery. Study Findings: Low-dose CT versus Chest X-ray screening 53,454 current and former smokers were randomly assigned to be screened once a year for 3 years with low-dose CT or chest X-ray. Here’s what happened after an average of 6.5 years: Low-dose CT Chest X-ray 26,722 people 26,732 people Benefit: How did CT scans help compared to chest X-ray, an ineffective screening test? 3 in 1,000 fewer died from lung cancer 18 in 1,000 versus 21 in 1,000 5 in 1,000 fewer died from all causes 70 in 1,000 versus 75 in 1,000 Harm: What problems did CT scans cause compared to chest X-ray? 223 in 1,000 more had at least one false alarm 365 in 1,000 versus 142 in 1,000 18 in 1,000 more had a false alarm leading to an invasive such as bronchoscopy, biopsy, or surgery procedure, 25 in 1,000 versus 7 in 1,000 2 in 1,000 more had a major complication from 3 in 1,000 versus 1 in 1,000 Invasive procedures “Take home” messages Lung cancer screening with CT scans is the only screening test shown to lower the chance of dying from lung cancer. -

About Lung Cancer What Is Lung Cancer?

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 About Lung Cancer Overview and Types If you have been diagnosed with lung cancer or are worried about it, you likely have a lot of questions. Learning some basics is a good place to start. ● What Is Lung Cancer? Research and Statistics See the latest estimates for new cases of lung cancer and deaths in the US and what research is currently being done. ● Key Statistics for Lung Cancer ● What’s New in Lung Cancer Research? What Is Lung Cancer? Lung cancer is a type of cancer that starts in the lungs. Cancer starts when cells in the body begin to grow out of control. To learn more about how cancers start and spread, see What Is Cancer?1 Normal structure and function of the lungs 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Your lungs are 2 sponge-like organs in your chest. Your right lung has 3 sections, called lobes. Your left lung has 2 lobes. The left lung is smaller because the heart takes up more room on that side of the body. When you breathe in, air enters through your mouth or nose and goes into your lungs through the trachea (windpipe). The trachea divides into tubes called bronchi, which enter the lungs and divide into smaller bronchi. These divide to form smaller branches called bronchioles. At the end of the bronchioles are tiny air sacs known as alveoli. The alveoli absorb oxygen into your blood from the inhaled air and remove carbon dioxide from the blood when you exhale. -

(NCCN Guidelines®) Thymomas and Thymic Carcinomas

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Thymomas and Thymic Carcinomas Version 2.2019 — March 11, 2019 NCCN.org Continue Version 2.2019, 03/11/19 © 2019 National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN. NCCN Guidelines Index NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2019 Table of Contents Thymomas and Thymic Carcinomas Discussion *David S. Ettinger, MD/Chair † Ramaswamy Govindan, MD † Sandip P. Patel, MD ‡ † Þ The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes- UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins Jewish Hospital and Washingtn University School of Medicine Karen Reckamp, MD, MS † ‡ *Douglas E. Wood, MD/Vice Chair ¶ City of Hope National Medical Center Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Matthew A. Gubens, MD, MS † Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance UCSF Helen Diller Family Gregory J. Riely, MD, PhD † Þ Comprehensive Cancer Center Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Dara L. Aisner, MD, PhD ≠ University of Colorado Cancer Center Mark Hennon, MD ¶ Steven E. Schild, MD § Roswell Park Cancer Institute Mayo Clinic Cancer Center Wallace Akerley, MD † Huntsman Cancer Institute Leora Horn, MD, MSc † Theresa A. Shapiro, MD, PhD Þ at the University of Utah Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins Jessica Bauman, MD ‡ † Rudy P. Lackner, MD ¶ Fox Chase Cancer Center Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center James Stevenson, MD † Case Comprehensive Cancer Center/ Ankit Bharat, MD ¶ Michael Lanuti, MD ¶ University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute Center of Northwestern University Ticiana A. -

Grade 6: the Heart and Circulatory System Lesson 1: the Heart Lesson 2: the Heart Rate Lesson 3: the Circulatory System and Blood

Grade 6: The Heart and Circulatory System Lesson 1: The Heart Lesson 2: The Heart Rate Lesson 3: The Circulatory System and Blood Objectives: 1. Students will identify the four chambers of the heart 2. Students will identify four important structures of the Circulatory System and what they do. 3. Students will explain heart rate and be able to take their resting and active heart rates. 4. Students will describe the major functions of the Circulatory System. 5. Students will explain the role of the heart in circulation 6. Students will give a basic explanation of the cardio-pulmonary sequence. 7. Students will describe systemic circulation. Materials: Lesson 1: • Animal heart (Example: cow, pig, sheep) • Note cards • Picture of the heart (See Figure 1) • Dissection tools (Scissors, pan, etc.) Lesson 2: • Small drum • Watch or clock with second hand, or time • Optional: Stethoscope Lesson 3: • Corn Syrup • Plastic Beads: flat red disks, white ovals, green or blue seed beads • “Explain” experiment (per group): o Two small balloons or large finger cots o One clear tube (1/2” diameter) about 8” long o One clear tube (3/4” diameter) about 8” long o 16 - 20 oz. water o Red food coloring o Measuring cup o Funnel o Two empty plastic containers (such as cottage cheese or yogurt cartons) Activity Summary: In this lesson students will learn the basic functioning of the heart, Circulatory System and blood, the connection to lung functioning, and the activity of the Grade 6: The Heart & Circulatory System – Revised 2008 Page 1 Circulatory System in the body. -

The Respiratory System

The Respiratory System Dr. Ali Ebneshahidi Functions of The Respiratory System • To allow gases from the environment to enter the bronchial tree through inspiration by expanding the thoracic volume. • To allow gas exchange to occur at the respiratory membrane, so that oxygen diffuses into the blood while carbon dioxide diffuses into the bronchial tree. • To permit gases in the lungs to be eliminated through expiration by decreasing the thoracic volume. General Anatomy of The Respiratory System 1. Consists of a tube that divides into small branching tubes in the lungs: external nares →nasal cavity → nasopharynx → laryngopharynx → larynx → trachea → primary bronchi → lungs (secondary bronchi → tertiary bronchi → bronchioles → alveolar sacs → alveoli). 2. The histology along the respiratory tract changes – from the trachea to the tertiary bronchi, the tract is lined with ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium, smooth muscle and cartilage rings; the bronchioles are lined with cuboidal epithelium; and from the alveolar ducts to the alveoli, the tract is lined with simple squamous epithelium. 3. The left lung contains 2 lobes – superior and inferior lobes, while the right lung contains 3 lobes – superior, middle, and inferior lobes. Each lobe is highly vascularized and contains part of the bronchial tree. 4. Inferior to the lungs is a sheet of skeletal muscle under involuntary control, called diaphragm, to facilitate the control of thoracic volume. Anatomy of Respiratory Organ 1. Nose and nasal cavity: • gases in the environment enter the respiratory tract through two openings called external nares which contain hairs to prevent dust particles to come in. • the space within the nose, called nasal cavity, is lined with ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium to provide a defense mechanism where cilia and mucus (from goblet cells) expel foreign substances.