An Appreciation of the Work of Ronald Perry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 July 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 20 July 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Social Tariffs: Torfaen 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Taxation: Electronic Hate Crime: Prosecutions 10 Government 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Technology and Innovation INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 10 Centres 20 Business: Broadband 10 UK Consumer Product Recall Review 20 Construction: Employment 11 Voluntary Work: Leave 21 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: CABINET OFFICE 21 Mass Media 11 Brexit 21 Department for Business, Elections: Subversion 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Electoral Register 22 Staff 11 Government Departments: Directors: Equality 12 Procurement 22 Domestic Appliances: Safety 13 Intimidation of Parliamentary Economic Growth: Candidates Review 22 Environment Protection 13 Living Wage: Jarrow 23 Electrical Safety: Testing 14 New Businesses: Newham 23 Fracking 14 Personal Income 23 Insolvency 14 Public Sector: Blaenau Gwent 24 Iron and Steel: Procurement 17 Public Sector: Cardiff Central 24 Mergers and Monopolies: Data Public Sector: Ogmore 24 Protection 17 Public Sector: Swansea East 24 Nuclear Power: Treaties 18 Public Sector: Torfaen 25 Offshore Industry: North Sea 18 Public Sector: Wrexham 25 Performing Arts 18 Young People: Cardiff Central -

The University of Exeter<Br>

News from the Universities The University of Exeter Initiatives in local, regional and community history The University of Exeter now operates on two separate campuses, Streatham Campus in Exeter and, since 2005, Tremough Campus near Falmouth, Cornwall. History at Exeter has expanded considerably in the last decade, partly as a result of the opening of the Tremough campus. There are now 27 full-time staff based at Streatham and another 10 in Tremough, with research interests extending from early Medieval Britain to post- Communist Eastern Europe. In the last five years there has also been a considerable intensification of activity in local and regional history, as History has sought to forge links with local community groups, institutions and other charitable and business organisations. In many respects staff at Tremough have taken the lead in developing these connections. A strong civic dimension has been developed within the History cluster at Tremough, with significant engagement with the Cornish community at a variety of levels. This was based initially on the long-standing work of the Institute of Cornish Studies, part of the University of Exeter but part-funded by Cornwall Council, and located in Cornwall well before the establishment of the Cornwall Campus. Since the early 1990s, the Institute has focused on issues of identity in modern Cornwall, which it has explored through a variety of methods—for example, biography, demography and oral history—and which has led among other things to the establishment of strong links with the overseas Cornish diaspora and to the publication of the annual volume Cornish Studies (University of Exeter Press). -

FINAL CAMBORNE Amended 15042010.Pub

Camborne Town Centre Conservation Area Character Appraisal & Management Strategy March 2010 This Conservation Area Appraisal and Management plan was commissioned by Kerrier District Council. It was endorsed by Cornwall Council as a material consideration within the emerging Cornwall Council Local Development Framework on 24 April 2010 (Cabinet ref- to add). The recommended changes to the boundaries of Camborne Conservation Area were authorised by Cornwall Council and came into effect on 24 April 2010. Contents Summary of special character 4 5.0 Issues and opportunities 36 10.0 Implementation of the plan 63 Boundary of the Conservation Area Strategic thinking 1.0 Introduction 5 Buildings at Risk Development control and enforcement actions Negative buildings Enhancement actions 2.0 Planning and Regeneration Context 6 Gap/opportunity sites Ongoing general actions National planning policies Public realm Funding and resourcing Local planning policy: existing Sustainability Adoption, monitoring and updating this plan Local planning policy: future Building Regs Part L Regeneration context 11.0 Bibliography 68 Part two Management Strategy 41 Appendix 1 Statement of Community Part One Appraisal 9 Involvement 69 6.0 Introduction 43 3.0 Influences on the Historic Development Appendix 2 Justification for extensions to of Camborne 11 7.0 Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and Conservation Area 84 Influences on Historical Development threats 44 Geology and topography Appendix 3 - Justification for Article 4 Influence of mining and engineering in -

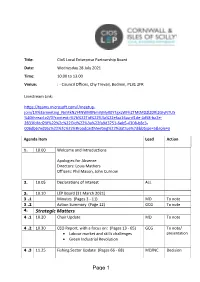

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local

Title: CIoS Local Enterprise Partnership Board Date: Wednesday 28 July 2021 Time: 10.00 to 13.00 Venue: : - Council Offices, Chy Trevail, Bodmin, PL31 2FR Livestream Link: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_NmFkNzY4NWMtNmVjMy00YTgxLWFhZTMtMDZlZDRlZGIyNTU5 %40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%22efaa16aa-d1de-4d58-ba2e- 2833fdfdd29f%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%22fa9d3751-6eb5-4308-b8c3- 006db67ed9ac%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d&btype=a&role=a Agenda Item Lead Action 1. 10.00 Welcome and Introductions Apologies for Absence Directors: Louis Mathers Officers: Phil Mason, John Curnow 2. 10.05 Declarations of Interest ALL 3. 10.10 LEP Board (31 March 2021) 3 .1 Minutes (Pages 3 - 11) MD To note 3 .2 Action Summary (Page 12) GCG To note 4. Strategic Matters 4 .1 10.20 Chair Update MD To note 4 .2 10.30 CEO Report, with a focus on: (Pages 13 - 65) GCG To note/ Labour market and skills challenges presentation Green Industrial Revolution 4 .3 11.25 Fishing Sector Update (Pages 66 - 68) MD/NC Decision Page 1 4 .4 11.50 Nominations Committee Update (Pages 69 - GCG Decision 122) 4 .5 12.15 Audit & Assurance Committee Update (Pages GCG Decision 123 - 198) 4 .6 12.25 Enterprise Zones Board Update (Pages 199 - SJ/GCG To note 202) 4 .7 12.35 Any other business 5. Exclusion of Press and Public 5 .1 12.40 Investment & Oversight Panel Update (Pages MD/GCG To note 203 - 206) 5 .2 12.50 Any other confidential business ALL Page 2 Agenda No. 3.1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP MINUTES of a Meeting of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership held in the Online - Virtual Meeting on Wednesday 31 March 2021 commencing at 10.00 am. -

Map Referred to in the Cornwall (Electoral Changes) Order 2011 D R a I Lw a Sheet 5 of 20 Y

SHEET 5, MAP 5 Electoral Divisions in Camborne and Ilogan Park Portreath 1 0 3 3 KEY B L L ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY Carvannel Downs I H A PARISH BOUNDARY E G E R PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY T PARISH WARD BOUNDARY Feadon Farm PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY MOUNT HAWKE AND PORTREATH ED ILLOGAN ED ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME CAMBORNE CP PARISH NAME PORTREATH CP TEHIDY PARISH WARD PARISH WARD NAME 1 0 3 3 B Carvannel Carvannel Farm Downs Mirrose Chytodden D is Well Cove m a n t le Map referred to in the Cornwall (Electoral Changes) Order 2011 d R a i lw a Sheet 5 of 20 y Penpraze Trengove Crane Islands Basset's Cove This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Tehidy Barton Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2011. Nursery r e t r a e t W a w W o ILLOGAN ED h A L LE Scale : 1cm = 0.08500 km g XA n i ND a RA H R e OA n D M a ILLOGAN Grid interval 1km e M PARISH WARD Golf Links C O T R Greenbank Cove O A NE D LA fs E lif IN C B h D rt OO o W N ILLOGAN CP Deadman's Cove Reskajeage Downs (National Trust) S P A R LA N E S O U T H D R Old Merrose Farm IV E I Derrick LL Merrose Farm O Cove iffs G Cl A rth N No D O W N S Home Farm Tehidy Park 01 B 33 TEHIDY Nursery PARISH WARD PARK BOTTOM PARISH WARD Downs Farm Magor Farm POOL AND TEHIDY -

The Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) Was Launched in May 2011

Written evidence submitted by Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (INS0039) The Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) was launched in May 2011. Private sector-led, it is a partnership between the private and public sectors and is driving the economic strategy for the region, determining local priorities and undertaking activities to drive growth and the creation of local jobs. Executive Summary The Government’s Industrial Strategy should be refreshed to include wider economic, social and environmental factors that are now in play post Covid 19 by building on all of England’s Local Industrial Strategies. Industrial Strategy Grand Challenges should be updated and localised, within a national framework, and should consider the levelling up agenda, climate change, regional imbalances and measures to reduce inequality/social inclusion. The refresh should use the guiding principle of devolving decision making and delivery. The focus on key sectors in the current Industrial Strategy is sufficient if a narrow view on “growth” is used or if “trickle down” economic policies are adopted. However, whilst this approach will raise the productivity and growth of some areas it will not benefit all areas equally and those areas furthest from key industrial centres will see little or no benefit. As the future prosperity of the UK depends on unlocking the potential of all its areas, towns, high streets businesses and residents the revised Industrial Strategy needs to be more inclusive and allow for different areas to make different contributions to overall productivity levels and growth. The immense productivity gap that currently exists between the prosperous South East of England and the rest of the country on the other must be therefore be levelled-up by investing in the LEP areas that are currently lagging behind. -

Corporate Business Plan 2016/17 – 2019/20

Business Plan 2016 - 2020 Delivering our Strategy www.cornwall.gov.uk Contents Page Foreword 2 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Our Strategy 3 1.2 Context 4 1.3 Our Corporate Business Plan 5 2. Progress to date – Strategic Overview: 6 Incorporates updates on the ‘Ambitious Cornwall’, ‘Engaging with our communities’ and ‘Partners working together’ strategic aims 3. Delivering the Council Strategy: Greater access, Driving the 10 economy, Stewarding the assets 3.1 Strategy, Economy, Enterprise & Environment 10 3.2 Commissioning & Asset Management 15 3.3 Planning & Enterprise 19 4. Delivering the Council Strategy: Healthier and safe 22 communities 4.1 Children’s Early Help, Psychology & Social Care 22 4.2 Commissioning Performance & Improvement 25 4.3 Adult Care & Support 29 4.4 Public Health 32 4.5 Learning and Achievement 35 4.6 Fire, Rescue and Community Safety 38 4.7 Public Protection 39 5. Delivering the Council Strategy: Being efficient, effective 45 and innovative 5.1 Customers and Communities 45 5.2 Business Planning & Development / People Management, 48 Development & Wellbeing 5.3 Governance and Information 51 6. Managing the Plan 54 6.1 Business & Service Planning 54 6.2 Performance management and reporting 55 6.3 Management of risk 55 6.4 Organisational development framework 56 7. Financial Resources 58 8. Conclusion 59 9. Acronyms 60 Corporate Business Plan 2016/17 – 2019/20 JOINT FOREWORD Welcome to the Council’s Business Plan for the next four years. When we approved our Council Strategy in 2014 we knew that we would be facing some significant challenges over the course of this decade, but also that there were tremendous opportunities for both the Council and for Cornwall if we worked with colleagues in the public, private and community sectors to deliver our ambition of creating a more sustainable and prosperous Cornwall that is resilient and resourceful, a place where communities are strong and where the most vulnerable are protected. -

Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues

Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues Paper - January 2012 Contents CORNWALL LDF: CORE STRATEGY PLACE-BASED ISSUES PAPER: CAMBORNE, POOL AND REDRUTH COMMUNITY 1 NETWORK AREA Summary 1 Purpose of paper 1 Camborne, Pool and Redruth Community Network Area 2 Key Facts 3 Introduction 5 Housing 6 Local Economy 8 Retail and Town Centres 10 Transport and Accessibility 12 Community facilities 14 People 16 Environment 18 Coast 20 Summary and Key Spatial Issues 22 Appendix A: Community Planning Area Visions / Key Objectives 22 Appendix B: Landscape Character information from the 2007 26 Cornwall Landscape Character Assessment Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues Paper - January 2012 Contents Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues Paper - January 2012 1 Cornwall LDF: Core Strategy Place-based Issues Paper: Camborne, Pool and Redruth Community Network Area Cornwall LDF: Core Strategy Place-based Issues Paper: Camborne, Pool and Redruth Community Network Area Summary Table .1 This paper summarises the key emerging issues for the Camborne and Redruth Community Network Area brought together to inform the Cornwall Core Strategy. The key issues: Issue 1 – Enable higher quality employment opportunities. Issue 2 – Manage the level and distribution of housing growth, taking into consideration the Camborne, Pool, Illogan, Redruth Area Action Plan research and evidence base. Issue 3 – Promote a positive relationship between the retail centres of Camborne, Pool and Redruth, strengthening comparison shopping. Issue 4 – Enhance sports and leisure facilities to serve population growth. Issue 5 – Reduce deprivation through allocation of land for services, open space and through high quality design. Issue 6 – Remediate contaminated land. Purpose of paper This is one of a series of papers whose main purpose is to identify the key issues for a specific area of Cornwall. -

Cornwall Local Plan: Community Network Area Sections

Planning for Cornwall Cornwall’s future Local Plan Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections www.cornwall.gov.uk Dalghow Contents 3 Community Networks 6 PP1 West Penwith 12 PP2 Hayle and St Ives 18 PP3 Helston and South Kerrier 22 PP4 Camborne, Pool and Redruth 28 PP5 Falmouth and Penryn 32 PP6 Truro and Roseland 36 PP7 St Agnes and Perranporth 38 PP8 Newquay and St Columb 41 PP9 St Austell & Mevagissey; China Clay; St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel 51 PP10 Wadebridge and Padstow 54 PP11 Bodmin 57 PP12 Camelford 60 PP13 Bude 63 PP14 Launceston 66 PP15 Liskeard and Looe 69 PP16 Caradon 71 PP17 Cornwall Gateway Note: Penzance, Hayle, Helston, Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth, Falmouth Penryn, Newquay, St Austell, Bodmin, Bude, Launceston and Saltash will be subject to the Site Allocations Development Plan Document. This document should be read in conjunction with the Cornwall Local Plan: Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections 2010-2030 4 Planning for places unreasonably limiting future opportunity. 1.4 For the main towns, town frameworks were developed providing advice on objectives and opportunities for growth. The targets set out in this plan use these as a basis for policy where appropriate, but have been moderated to ensure the delivery of the wider strategy. These frameworks will form evidence supporting Cornwall Allocations Development Plan Document which will, where required, identify major sites and also Neighbourhood Development Plans where these are produced. Town frameworks have been prepared for; Bodmin; Bude; Camborne-Pool-Redruth; Falmouth Local objectives, implementation & Penryn; Hayle; Launceston; Newquay; Penzance & Newlyn; St Austell, St Blazey and Clay Country and monitoring (regeneration plan) and St Ives & Carbis Bay 1.1 The Local Plan (the Plan) sets out our main 1.5 The exception to the proposed policy framework planning approach and policies for Cornwall. -

Redruth Main Report

Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration REDRUTH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Objective One is part-funded by the European Union Cornwall and Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration REDRUTH Kate Newe ll June 2004 HES REPORT NO. 2004R037 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Environment and Heritage Service, Planning Transportation and Estates, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] Acknowledgements This report was produced as part of the Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey project (CSUS), funded by English Heritage, the Objective One Partnership for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (European Regional Development Fund) and the South West Regional Development Agency (South West RDA). Peter Beacham (Head of Designation), Graham Fairclough (Head of Characterisation), Roger M Thomas (Head of Urban Archaeology), Jill Guthrie (Designation Team Leader, South West) and Ian Morrison (Ancient Monuments Inspector for Devon, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly) liaised with the project team for English Heritage and provided valuable advice, guidance and support. Nick Cahill (The Cahill Partnership) acted as Conservation Advisor to the project, providing support with the characterisation methodology and advice on the interpretation of individual settlements. Georgina McLaren (Cornwall Enterprise) performed an equally significant advisory role on all aspects of economic regeneration. Additional help has been given by Andrew Richards (Conservation Officer, Kerrier District Council). Mike Horrocks (then Community Regeneration Officer Redruth Area, Tin Country Partnership, IAP) and John Dobson (then Camborne – Pool – Redruth Principal Regeneration Manager Objective 1, South West RDA) provided valuable information regarding regeneration proposals and initiatives. -

ERDF Convergence Progress Report, Jun 2014 DRAFT.Pub

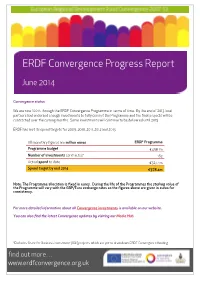

ERDF Convergence Progress Report June 2014 Convergence status We are now 100% through the ERDF Convergence Programme in terms of time. By the end of 2013 local partners had endorsed enough investments to fully commit the Programme and the final projects will be contracted over the coming months. Some investments will continue to be delivered until 2015. ERDF has met its spend targets for 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. All monetary figures are million euros ERDF Programme Programme budget €458.1m Number of investments contracted* 163 Actual spend to date €327.4m Spend target by end 2014 €378.4m Note: The Programme allocation is fixed in euros. During the life of the Programmes the sterling value of the Programme will vary with the GBP/Euro exchange rates so the figures above are given in euros for consistency. For more detailed information about all Convergence investments is available on our website. You can also find the latest Convergence updates by visiting our Media Hub. *Excludes Grant for Business Investment (GBI) projects which are yet to draw down ERDF Convergence funding. find out more… www.erdfconvergence.org.uk CONVERGENCE INVESTMENTS New Investments Apple Aviation Ltd Apple Aviation, an aircraft maintenance, repair and overhaul company, has established a base at Newquay Airport’s Aerohub. Convergence funding from the Grant for Business Investment programme will contribute to salary costs for thirteen new jobs in the business. ERDF Convergence investment: £211,641 (through the GBI SIF) Green Build Hub Located alongside the Eden Project, the Green Build Hub will be a research facility capable of demonstrating and testing the performance of innovative sustainable construction techniques and materials in a real building setting. -

Weekly Newsletter Spring 5 8Th February 2019 01209 713929 [email protected] @Penponds School

Weekly Newsletter Spring 5 8th February 2019 www.penponds.cornwall.sch.uk 01209 713929 [email protected] @Penponds_School This week’s focus: Letter from the Education Secretary Dates for your diary: This week the school received a lovely letter from Damian Hinds MP, the Education ……………………………………. Secretary, for our standards in Reading and Maths. It is not often that schools receive Monday 11th February– such letters so I have published it below. Thank you for your continued support. NEXUS Maths Masterclass Adam Richards, Headteacher 8.55am Tuesday 12th February – Mousehole Trip for Carn Brea and Trencrom classes Thursday 14th February – Open Afternoon in Carn Brea Class Friday 15th February 5.30pm to 7pm – Valentine Disco …………………………………….. 18th-22nd February – half- term break ……………………………………… Tuesday 26th February – King Edward Mine Trip for Tregonning Class Thursday 28th February – Breadmaking in Class 3 …………………………………….. Monday 4th March NEXUS Maths Masterclass 8.55am Wednesday 6th March – World Book Day celebrations – dress up day and Snuggledown at 6pm Wednesday 6th March – Taste the World/Rainbow Choices for Class 3 in the Hall ………………………………………. 11th-15th March – British STEM week Monday 11th March – Shoebox Racer Competition Tuesday 12th March – Cornwall Records Office Trip – Trencrom and Tregonning Classes Thursday 14th March – Science Adventures Show – in the Hall Safer Internet day …………………………………….. All the classes have celebrated Safer Internet day this week and investigated various Monday 18th March ways of keeping themselves safe online. Godolphin Class shared the story of Smartie NEXUS Maths Masterclass the penguin from; https://www.childnet.com/resources/smartie-the-penguin 8.55am The children learned how to cope if pop-ups appear on a game on a tablet, what to Tuesday 19th March – do if people are unkind online and what happens if a website is not for their age Parent meetings group.