II Model – Nasreen Mohamedi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christie's First Auction in India Makes Inr 96,59,37,500

PRESS RELEASE | MUMBAI FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 19 December 2013 CHRISTIE’S FIRST AUCTION IN INDIA MAKES INR 96,59,37,500 /US$15.4 MILLION DOUBLING PRE-SALE ESTIMATES UNTITLED BY VASUDEO S. GAITONDE SELLS FOR INR 23,70,25,000 (US$3.7MILLION) HIGHEST PRICE FOR A MODERN WORK OF ART SOLD IN INDIA WORKS FROM THE GANDHY ESTATE TOTALS INR 26,10,70,000 (US$4.1 MILLION) Auctioneer, Dr. Hugo Weihe, International Director of Asian Art, sells Vasudeo S. Gaitonde‟s Untitled work for INR 23,70,25,000 (USD$3,792,400) at Christie‟s first auction in India. Mumbai – This evening in Mumbai, Christie‟s first auction in India totaled INR 96,59,37,500 (USD$15,455,000), doubling pre-sale expectations and selling 98% by lot. This auction marks an historic moment for Christie‟s, building on a 20-year history in India, and a decade of global market leadership in Modern Indian Art through sales in New York and London. At this evening‟s auction buying came from around India, across Asia, the US and Europe, reflecting both the world-wide interest in this category and Christie‟s global reach. The pre-sale exhibitions during the past two weeks in New Delhi and Mumbai attracted many visitors and interest from both new and existing clients was so great at this evening‟s auction that an extra room had to be prepared to accommodate clients. The sale was held at The Taj Mahal Palace, Mumbai. “It has been a true privilege to be in India where we have been honoured by the warm welcome. -

Nasreen Mohamedi: Untitled, Undated

Milton Keynes Gallery Nasreen Mohamedi: Untitled, Undated. Pen, pencil and ink on paper (49.5cm x 69 cm) Courtesy Glenbarra Art Museum Collection, Japan Nasreen Mohamedi 5 September – 15 November 2009 Preview: Friday 4 September 18.00-20.00 Milton Keynes Gallery Nasreen Mohamedi 5 September – 15 November 2009 Preview: Friday 4 September 18.00-20.00 Media Partner: ArtAsia Pacific Magazine Exhibition supported by The Charles Wallace Trust India, The Red Hot World Buffet, The Nehru Centre and the Nasreen Mohamedi Circle of Friends, including Modern Art and those who wish to remain anonymous Milton Keynes Gallery is delighted to announce a major solo exhibition of work by important Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi. Her diary pages, drawings and photographs combine Western influences such as Paul Klee and Kasimir Malevich with Islamic architectural forms and a South Asian sensibility, resulting in an intensely personal body of work. Born in Karachi, India (now Pakistan) in 1937, Mohamedi created a highly developed language from the 1950s to the 1980s. Early drawings often suggest plants and trees, before the artist focused on creating variations around the grid format; later works present free-floating geometric forms that evoke futuristic, mechanical or architectural devices. These abstract forms were often developed in intricately detailed diaries, written throughout the artist’s life, where the written word morphs into personalised symbols, grids and diagonals. The artist traces or weaves regular patterns in her drawings, as if mapping a pulse or internal flow onto external phenomena. Her tightly cropped photographs seek out elemental forms such as the repetitive patterns found in the sea or landscapes as well as in the constructed world, in architecture and urban design. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

A Fragile Inheritance

Saloni Mathur A FrAgile inheritAnce RadicAl StAkeS in contemporAry indiAn Art Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian Art ·· · 2019 © 2019 All rights reserved Printed in the United States o America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Quadraat Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library o Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Mathur, Saloni, author. Title: A fragile inheritance : radical stakes in contemporary Indian art / Saloni Mathur. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identi£ers: ¤¤ 2019006362 (print) | ¤¤ 2019009378 (ebook) « 9781478003380 (ebook) « 9781478001867 (hardcover : alk. paper) « 9781478003014 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: ¤: Art, Indic—20th century. | Art, Indic—21st century. | Art—Political aspects—India. | Sundaram, Vivan— Criticism and interpretation. | Kapur, Geeta, 1943—Criticism and interpretation. Classi£cation: ¤¤ 7304 (ebook) | ¤¤ 7304 .384 2019 (print) | ¤ 709.54/0904—dc23 ¤ record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006362 Cover art: Vivan Sundaram, Soldier o Babylon I, 1991, diptych made with engine oil and charcoal on paper. Courtesy o the artist. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the ¤ Academic Senate, the ¤ Center for the Study o Women, and the ¤ Dean o Humanities for providing funds toward the publication o this book. ¶is title is freely available in an open access edition thanks to the initiative and the generous support o Arcadia, a charitable fund o Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, and o the ¤ Library. vii 1 Introduction: Radical Stakes 40 1 Earthly Ecologies 72 2 The Edice Complex 96 3 The World, the Art, and the Critic 129 4 Urban Economies 160 Epilogue: Late Styles 185 211 225 I still recall my £rst encounter with the works o art and critical writing by Vivan Sundaram and Geeta Kapur that situate the central concerns o this study. -

The South Asian Art Market Report 2017

The South Asian Art Market Report 2017 ° Colombo The South Asian Art Market Report 2017 INTRODUCTION It’s 10 years ago since we published our first art market report Yes, the South Asian art market still lacks government support on the South Asian art market, predominantly focusing on India, compared to other Asian art markets (China’s for instance), but and I am very excited to see a market that is in a new, and I private foundations are gradually filling the vacuum. What the would argue, much healthier cycle. Samdani Art Foundation in Dhaka has managed to achieve with the Dhaka Art Summit is a great example. The South Asian art The South Asian art market boom between 2004 and 2008 market needs more champions like this, and with South Asian was exciting, because it made this regional art market gain economies being among the fastest growing in the world, the proper international attention for the first time, and laid the requisite private wealth would appear available to support it. foundation for much of the contemporary gallery, art fair and I am very excited to publish this report after 10 years of auction infrastructure we see today. However, there was also monitoring and following this market as, for the first time since a destructive side to these boom years, felt shortly after the 2008, I sense a different type of optimism. Unlike the sheer financial crisis in 2009, when the top 3 auction houses market euphoria of 2008, this is something more tangible; recorded a 66% drop in sales of modern and South Asian biennials and festivals are getting more contemporary art and the share of contemporary international attention; initiatives are being set art dropped from 41% in 2008 to 12% in 2009; up to support artists and artistic exchange; and the dangers of speculation were manifested. -

Nasreen Mohamedi. Waiting Is a Part of Intense Living

Nasreen Mohamedi. Waiting is a part of intense living DATE: September 23, 2015 - January 11, 2016 PLACE: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Sabatini Building. 3rd Floor ORGANIZATION: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi CURATORSHIP: Roobina Karode COORDINATOR: Soledad Liaño EXHIBITION TOUR: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Nueva York (18 March - 5 June, 2016) RELATED ACTVITIES: Discussion on Nasreen Mohamedi, with two keynote speeches and a subsequent debate between Roobina Karode and Geeta Kapur, to be held in Auditorium 200. September 23, 7 pm. The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York in collaboration with Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, have organized the most complete retrospective, so far, on the Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937- 1990), a leading pioneer of modern abstract art in Asia. The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in collaboration with the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, have organized the most complete retrospective yet held on the Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990), one of the first artists to embrace the languages of modern abstraction in Asia. Despite her outstanding contributions and her status as one of the most internationally renowned Indian artists, Mohamedi’s art has never yet been shown in its totality. On this occasion, 216 works, mostly ink and graphite drawings, photographs, watercolors and a small number of oils on canvas and collages, show the evolution of her work from the late 1950s to the early 1980s, with special emphasis on the work she did in the 1970s. -

July 2020 SONAL KHULLAR Department of the History of Art

SONAL KHULLAR Department of the History of Art University of Pennsylvania Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe History of Art Building 3405 Woodland Walk Philadelphia, PA 19104 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of California at Berkeley, 2009 History of Art with a Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality Committee: Joanna G. Williams, Anne M. Wagner, Whitney M. Davis, Lawrence Cohen M.A. University of California at Berkeley, 2004 History of Art B.A. Wellesley College, 2000 Comparative Literature and Economics, summa cum laude ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2020- W. Norman Brown Associate Professor of South Asian Studies Department of the History of Art, University of Pennsylvania 2015-2020 Associate Professor of Art History, School of Art + Art History + Design Adjunct Associate Professor of Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies Affiliated Faculty, South Asian Studies Program, Jackson School of International Studies Affiliated Faculty, Center for Communication, Difference, and Equity University of Washington 2009-2015 Assistant Professor of Art History, School of Art + Art History + Design Adjunct Assistant Professor of Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies Affiliated Faculty, South Asian Studies Program, Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington PUBLICATIONS (peer-reviewed marked with *) Book *Worldly Affiliations: Artistic Practice, National Identity, and Modernism in India, 1930-1990. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015. Reviewed in: • Choice: Current Reviews for Academic Libraries 53, no. 9 (May 2016): 1318, by Dale K. Haworth. • The Art Bulletin 98, no. 2 (June 2016): 267-269, by Emilia Terraciano. • The Comparatist 40, no. 1 (October 2016): 338-346, by Elizabeth Miller. July 2020 1 • caa.reviews (December 4, 2018), doi: 10.3202/caa.reviews.2018.241, by Holly Shaffer. -

With Frugal Means: Nasreen Mohamedi

This text is an unedited draft on the basis of which the speaker delivered a seminar, talk or lecture at the venue(s) and event(s) cited below. The title and content of each presentation varied in response to the context. There is a slide-show below that accompanies this document. If the text has been worked upon and published in the form of an essay, details about the version(s) and publication(s) are included in the section pertaining to Geeta Kapur’s published texts. Venue • ‘Re – Presenting Histories’, Workshop in School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, New Delhi, 23rd January 2009. Organized by Grant Watson and Suman Gopinath, OCA, Oslo With frugal means: Nasreen Mohamedi With more calibrated histories of modern art available in different parts of the world, the jaded notion of ‘influence’ is likely to fade out of the critical apparatus. Instead we can work with a productive paradox: to navigate uncharted trajectories connecting artists working with approximately similar quests, but different diachronic frames and widely separated geographies. Relatedly, to regard the auteur as original and autonomous but also affiliated with colleagues known and unknown; and to understand the artist’s form and style as conjunctural -- based on creative exigency rather than the privilege of chronology and place. Do we then arrive at a more complex understanding of the universal in art history, or do we abandon the universal as the enlightenment’s meta-narrative of individual sovereignty with a unitary and hegemonic ideology reinforcing its source in the modern west? Art history as a discipline is now struggling with these issues, its cadres divided into global art advocates and their more varied detractors. -

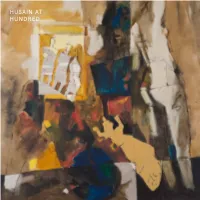

Husain at Hundred

HUSAIN AT HUNDRED Title TK 1 HUsaIN at HUNDRED M.F. HUSAIN AICON GALLERY, NEW YORK SEPTEMBER 17 - OctOBER 24, 2015 2 Title TK Cover: Untitled (The Three Muses, Maya Series), 1965, oil on canvas, 68 x 60 in. Foreword “…in ‘48 I came out with five paintings, which was the of Modern artists in India, seeking new forms of elevated himself from the ordinary man to a turning point in my life. I deliberately picked up two or expression to capture and convey India’s complex distinctive icon. three periods of Indian history. One was the classical past, along with its emerging post-colonial future. Entering into the 1980s and 1990s, Husain period of the Guptas, the very sensuous form of the The fusion of Indian subject matter with Post- painted his country with the eye of a man who female body. Next was the Basohli1 period, the strong Impressionist colors, Cubist forms and Expressionist knew his subject uncomfortably well; he knew colors of the Basohli miniatures. The last was the folk gestures forged a synthesis between early European India’s insecurities, blemishes and inner turmoil. element. With these three combined, and using colors modernist techniques and the ever-shifting cultural Beyond the controversy that eventually led him very boldly as I did with cinema hoardings, I went to and historical identities of India. into exile, he was above all an artist radically and town. That was the breaking point…to come out of Since his beginnings in the 1940s, Husain permanently redefining Indian art, while remaining the influence of the British academic painting and sought to radically redefine and redirect the unafraid to confront the growing social and the Bengal Revivalist School.” course of Indian painting, paving the way for political issues of his country’s transformations. -

Arts Illustrated .Vol 3 Issue 5 Market Matters - Highlighted.Pdf

Market Matters Quicken, Saad Qureshi, Mixed Media including Wood, Cement, Wattle and Daub, Paint, 900 cm x 200 cm, 2011 Image Courtesy of the Artist The Other Side By Premala Matthen INDIAN Art HAS CErtAINLY CREATED A NICHE FOR ITSELF IN THE INTERNATIONAL Art MARKET, WITH SIGNIFICANT NEW TRENDS STArtING TO EMERGE, IRREVOCABLY CHANGING THE WAY INDIAN Art IS PERCEIVED BY THE WEST n December 15, 2015, at a Christie’s collectors: $4.01 million for the F.N. Souza auction in Mumbai, a Vasudeo S ‘Birth’ (1955) in September and $2.92 million Gaitonde painting, ‘Untitled’ (1995), for the Amrita Sher-Gil ‘Untitled (Self-Portrait)’ Osold at an all-time record price for Indian art (1933) in March, both sold in New York. at $4.4 million. It is said to be bought by an Record price points are not in and of themselves international collector based outside India who is valuable; however, these headline-grabbing not of Indian origin. In fact, Christie’s confirms figures send a clear message of confidence and that the top lot for each of its three India sales positive sentiment to the international art world were all bought from outside the country. Two by increasing recognition for Indian artists, and other record prices for Indian art were achieved encouraging interest for new buyers to look for in that same year, also bought by international opportunities. 80 / ARTS ILLUSTRATED / FEB 2016 - MAR 2016 /IAF - Delhi Connectig Art In the past few decades there have been several non-Indian mega-collectors who have single-handedly buoyed the Indian modern and contemporary art market. -

News Release

News Release The Metropolitan Museum of Art Communications Department 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10028-0198 tel (212) 570-3951 fax (212) 472-2764 [email protected] Nasreen Mohamedi March 18–June 5, 2016 Exhibition Location: The Met Breuer, 2nd floor, Madison Avenue and 75th Street Press Preview: Tuesday, March 1, 10:00 a.m.–1:00 p.m. Celebrating one of the most important artists to emerge in post-Independence India, and marking the first museum retrospective of the artist’s work in the United States, Nasreen Mohamedi examines the career of an artist whose singular and sustained engagement with abstraction adds a rich layer to the history of South Asian art and to modernism on an international level. The retrospective will span the entire career of Mohamedi (1937– 1990)—from her early works in the 1960s through her late works on paper in the 1980s—exploring the conceptual complexity and visual subtlety that made her work unique for its time, and demonstrating why she is considered one of the most significant artists of her generation. Together with the thematic exhibition Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, Nasreen Mohamedi will inaugurate The Met Breuer, which expands upon the Met’s modern and contemporary art program, when it opens to the public on March 18, 2016. The exhibition is organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, with the collaboration of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. “We are proud to present Nasreen Mohamedi in our first wave of exhibitions at The Met Breuer,” said Thomas P. -

A Fragile Inheritance: Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian

A FrAgile inheritAnce This page intentionally left blank Saloni Mathur A FrAgile inheritAnce Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian Art Duke univerSity PreSS · DurhaM anD lonDon · 2019 © 2019 Duke univerSity PreSS This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Quadraat Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Mathur, Saloni, author. Title: A fragile inheritance : radical stakes in contemporary Indian art / Saloni Mathur. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2019006362 (print) | lccn 2019009378 (ebook) iSbn 9781478003380 (ebook) iSbn 9781478001867 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9781478003014 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Art, Indic—20th century. | Art, Indic—21st century. | Art—Political aspects—India. | Sundaram, Vivan— Criticism and interpretation. | Kapur, Geeta, 1943—Criticism and interpretation. Classification: lcc n7304 (ebook) | lcc n7304 .M384 2019 (print) | DDc 709.54/0904—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006362 Cover art: Vivan Sundaram, Soldier of Babylon I, 1991, diptych made with engine oil and charcoal on paper. Courtesy of the artist. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the ucla Academic Senate, the ucla Center for the Study of Women, and the ucla Dean of Humanities for providing funds toward the publication of this book. This title is freely available in an open access edition thanks to the toMe initiative and the generous support of Arcadia, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, and of the ucla Library.