Of Accountability and Punishment in Congress Rajesh Singh, Visiting Fellow, VIF 31 Oct 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYNOPSIS 1. the Petitioner Herein Prefers the Present Petition in Public

SYNOPSIS 1. The Petitioner herein prefers the present petition in public interest, under Article 32 of the Constitution of India 1950, challenging the constitutional validity of the Right to Information (Amendment) Act, 2019 and its accompanying rules namely the ‘Right to Information (Term of Office, Salaries, Allowances and Other Terms and Conditions of Service) Rules, 2019, on the grounds, inter-alia that Impugned amendments: - I. Are violative of object of the parent statute itself. There is no rational nexus between the Amendment Act/Rules and the object of the Act itself. II. It infringes fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 19(1)(a) and 21 of the Constitution. III. There is non-application of mind in enacting the impugned amendments. IV. The impugned amendments have been enacted based on extraneous considerations. V. Contrary to the law laid down by this Hon’ble Court. 2. The RTI Act 2005 is a salutary piece of legislation aimed at promoting transparency in public administration and empowering the common citizen. The said Act created Central and State Public Information Officers (‘PIOs’) for disclosure of information as well as Central Information Commission (‘CIC’) and State Information Commissions (‘SIC’), consisting of ‘Information Commissioners’ to adjudicate on denial of information. 3. The RTI Act contained several in-built safeguards to ensure the independence of Information Commissioners appointed to the CIC or SICs which are as follows :- 3.1 A non-partisan procedure of appointment of the CIC and the SICs under Section 12(3) and 15(3) respectively of the RTI Act that includes a member of the opposition party in the selection committee. -

Constitution & Rules of the Indian National Congress

CONSTITUTION & RULES OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS (As amended upto 83rd Plenary Session, 18-20 December 2010) Article I OBJECT The object of the Indian National Congress is the well-being and advancement of the people of India and the establishment in India, by peaceful and constitutional means, of a Socialist State based on Parliamentary Democracy in which there is equality of opportunity and of political, economic and social rights and which aims at world peace and fellowship. Article II Allegiance to Constitution of India The Indian National Congress bears true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India as by law established and to the principles of socialism, secularism and democracy and would uphold the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India. Article II-A Party Flag The flag of the Indian National Congress shall consist of three horizontal colours: saffron, white and green with the picture of a Charkha in Blue in the Centre. It shall be made of certified Khadi. Article III Constituents The Indian National Congress will include the plenary and special sessions of the Congress and, (i) The All India Congress Committee, (ii) The Working Committee, (iii) Pradesh Congress Committees, (iv) District/City Congress Committees, (v) Committees subordinate to the District Congress Committee like Block or Constituency Congress Committee and other subordinate Committee to be determined by the Pradesh Congress Committee concerned. Note: In this Constitution wherever the word "Pradesh" occurs, it will include "Territorial", the word "District" will include "City" as required by the context. ___________________________________________________________________ Rule Under Article III (iv) – Constituents – City Congress Committee : The Pradesh Congress Committee with previous approval of the Working Committee will have the right to constitute City Congress Committee in the cities with population of over Five lakh. -

Ramesh 'Disagrees Completely' with Pawar Over Bt Brinjal

22-1-2010 Ramesh 'disagrees completely' with P… Home | Rec ommend Us | Contact us | Make NK your default homepage Search TOP NEWS BREAKING NEWS HOM E | ASTROLOGY | CHINESE ASTROLOGY | NUM EROL OGY | RECIPES | SELF HELP | PHOTO GALLERY | YOGA | TRAVEL | EDUC A T ION | PINCODES | BABY NAM ES NEWS CHANNELS Kerala News Free Indian Horoscope Home > News > india•news From a Vedic Astrologer. Discover Now your India News Future for next Months World News Ramesh 'disagrees completely' with AboutAstro.com/horoscope Business India ExportSubsidie India? Sports News Pawar over Bt Brinjal U kunt 35% Subsidie krijgen voor Export naar India! Cricket News Antwoordvoorbedrijven.nl/Subsidie New Delhi, Jan 21: Environment Minister Jairam Travel News Ramesh Thursday took on Agriculture Minister Vergroot uw rendement Health News Werf snel en eenvoudig uw personeel vanaf Sharad Pawar over permitting commercial €649,! Technology Hiring.Monsterboard.nl cultivation of genetically modified brinjal, after Literature News Liquid Fertilizers Education News Pawar was quoted as saying an expert committee's Custom made formulations Industrial solution, Wastewater Agriculture News clearance to this effect was final. Ramesh wrote to www. e u ro l i q u i d s . co m Autom obile News Pawar, saying he "completely disagreed" with Real Estate News Pawar's view. Special Features The PHOTO GALLERY Bt 75 government's Sharp Camcorder Accu's nodig? Bestel Genetic Bollyw ood Photos Entertainment New s voor 21.00u, Morgen in Huis. Holly w ood Photos ReplaceDirect.com/bt+75 Engineering -

![Fuuyrg¶D 2XYRUZ Hz D >RYR T]ZWWYR Xvc](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0007/fuuyrg%C2%B6d-2xyruz-hz-d-ryr-t-zwwyr-xvc-320007.webp)

Fuuyrg¶D 2XYRUZ Hz D >RYR T]ZWWYR Xvc

/ 0 =0 !> ,!> > VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"#0$"T utqBVQWBuxy( 345"3# (6/0 &+-+&- 4 &1% 23 5,-,# 26 ) "6)6<<8"*65./ 7 3-16 /?7* 480*"*.//? 08/*/31567 46./434.58-7.< ).-*65.4/8 <.51*<.*3< 1.50*".< *5**.*C8- -34685.--.?-163< 08<.035 ?08<.4.0C*.?7.0. @/1 12"+$A33* B$9 @.- ,8. 7 87 1 98$-:& /, R R & 3 4.* Pawar — who had earlier in the afternoon, resigned as the n an anti-climax to a month- Deputy Chief Minister and R Ilong unprecedented political returned to the parent party — drama in Maharashtra, the would attend the MVA’s joint BJP’s surreptitious effort to legislature party meeting, but install its Government fizzled he was not present there. out on Tuesday afternoon as The NCP leaders attributed Chief Minister Devendra Ajit Pawar’s absence to his Fadnavis resigned from his uneasiness and hesitation to be post after the NCP’s rebel at the meeting, especially after leader Ajit Pawar, the Deputy the developments in the last Chief Minister, pulled out of few days. R the new dispensation under Earlier, talking to media tremendous pressure from his persons before handing over 58708/* parent party. his resignation to the Within hours after the Governor, Fadnavis said he he Supreme Court’s Supreme Court put a break to had decided to put in his TTuesday morning order a possible horse-trading by papers, “after Ajit met him, directing Maharashtra Chief * $ + (% ordering a floor test in the State expressed his inability to con- Minister Devendra Fadnavis to , * + % (% Assembly by 5 pm on tinue in the BJP-led hold trust vote on Wednesday ( - !( . -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

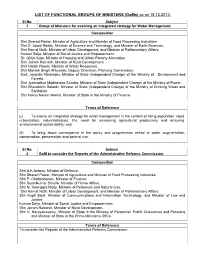

LIST of FUNCTIONAL GROUPS of MINISTERS (Goms) As on 18.12.2013

LIST OF FUNCTIONAL GROUPS OF MINISTERS (GoMs) as on 18.12.2013. Sl.No. Subject 1 Group of Ministers for evolving an integrated strategy for Water Management. Composition Shri Sharad Pawar, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Food Processing Industries. Shri S. Jaipal Reddy, Minister of Science and Technology, and Minister of Earth Sciences. Shri Kamal Nath, Minister of Urban Development, and Minister of Parliamentary Affairs. Kumari Selja, Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment. Dr. Girija Vyas, Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation. Shri Jairam Ramesh, Minister of Rural Development. Shri Harish Rawat, Minister of Water Resources. Shri Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission. Smt. Jayanthi Natarajan, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Environment and Forests. Shri Jyotiraditya Madhavrao Scindia, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Power. Shri Bharatsinh Solanki, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. Shri Namo Narain Meena, Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance. Terms of Reference (i) To evolve an integrated strategy for water management in the context of rising population, rapid urbanization, industrialization, the need for increasing agricultural productivity and ensuring environmental sustainability; and (ii) To bring about convergence in the policy and programmes aimed at water augmentation, conservation, preservation and optimal use. Sl.No. Subjec t 2 GoM to consider the Reports of the Administrative Reforms Commission. Composition Shri A.K.Antony, Minister of Defence. Shri Sharad Pawar, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Food Processing Industries. Shri P. Chidambaram, Minister of Finance. Shri Sushilkumar Shinde, Minister of Home Affairs. -

A Number of Decisions Made by the Rajiv Gandhi Government

Back to the Future: The Congress Party’s Upset Victory in India’s 14th General Elections Introduction The outcome of India’s 14th General Elections, held in four phases between April 20 and May 10, 2004, was a big surprise to most election-watchers. The incumbent center-right National Democratic Alliance (NDA) led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had been expected to win comfortably--with some even speculating that the BJP could win a majority of the seats in parliament on its own. Instead, the NDA was soundly defeated by a center-left alliance led by the Indian National Congress or Congress Party. The Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s, had been written off by most observers but edged out the BJP to become the largest party in parliament for the first time since 1996.1 The result was not a complete surprise as opinion polls did show the tide turning against the NDA. While early polls forecast a landslide victory for the NDA, later ones suggested a narrow victory, and by the end, most exit polls predicted a “hung” parliament with both sides jockeying for support. As it turned out, the Congress-led alliance, which did not have a formal name, won 217 seats to the NDA’s 185, with the Congress itself winning 145 seats to the BJP’s 138. Although neither alliance won a majority in the 543-seat lower house of parliament (Lok Sabha) the Congress-led alliance was preferred by most of the remaining parties, especially the four-party communist-led Left Front, which won enough seats to guarantee a Congress government.2 Table 1: Summary of Results of 2004 General Elections in India. -

Emerging Kerala 2012 a Global Connect Initiative

Government of Kerala Emerging Kerala 2012 A Global Connect Initiative FACT SHEET Date : 12 – 14 September 2012 Venue : Hotel Le-Meridian, Kochi, Kerala. Event Objective Objective of this Global Connect Initiative is to bring all stakeholders who are prime drivers of economy to engage in policy dialogues with the Government towards formulating a collective vision as well as to facilitate business to business linkages to enable growth. The event would also make Kerala a premier global hub of economic activity, through fostering entrepreneurship and industry, which could leverage its inherent strengths, resulting in equitable socio-economic growth. Plenary Sessions : a) Kerala Developmental Model: Enabling Faster Inclusive and Sustainable Growth b) Bridging the Infrastructure Gap: Role of PPPs to Spur Growth c) Manufacturing, International Trade and Exports d) Financial Reforms for Inclusive Growth Sectoral Conferences : Defence & Aerospace; Green Energy & Environmental Technologies; Financial Services; Food & Agro Processing; Healthcare; Education; Infrastructural Development; IT and IT Enabled Services; Manufacturing; MSMEs; Ports, Logistics and Ship Building; Science & Technology (Bio Technology, Nano Technology and Life Sciences), Tourism etc. Key Speakers / : Chief Guest: Dr Manmohan Singh, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India. Guests of Dignitaries Honour and Other Key Dignitaries: Mr Oommen Chandy, Hon’ble Chief Minister of Kerala; Mr A K Antony, Defence Minister; Mr Ghulam Nabi Azad, Minister of Health and Family Welfare; Dr Farooq Abdulla, -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4158–4180 1932–8036/20170005 Fragile Hegemony: Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India SUBIR SINHA1 School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK Direct and unmediated communication between the leader and the people defines and constitutes populism. I examine how social media, and communicative practices typical to it, function as sites and modes for constituting competing models of the leader, the people, and their relationship in contemporary Indian politics. Social media was mobilized for creating a parliamentary majority for Narendra Modi, who dominated this terrain and whose campaign mastered the use of different platforms to access and enroll diverse social groups into a winning coalition behind his claims to a “developmental sovereignty” ratified by “the people.” Following his victory, other parties and political formations have established substantial presence on these platforms. I examine emerging strategies of using social media to criticize and satirize Modi and offering alternative leader-people relations, thus democratizing social media. Practices of critique and its dissemination suggest the outlines of possible “counterpeople” available for enrollment in populism’s future forms. I conclude with remarks about the connection between activated citizens on social media and the fragility of hegemony in the domain of politics more generally. Keywords: Modi, populism, Twitter, WhatsApp, social media On January 24, 2017, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), proudly tweeted that Narendra Modi, its iconic prime minister of India, had become “the world’s most followed leader on social media” (see Figure 1). Modi’s management of—and dominance over—media and social media was a key factor contributing to his convincing win in the 2014 general election, when he led his party to a parliamentary majority, winning 31% of the votes cast. -

White Paper on the Management of COVID-19 by the Government of India

White Paper on the Management of COVID-19 by the Government of India JUNE 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary…………………………………………... (i) 2. The Need for a White Paper on the Management of the COVID-19 Pandemic………………………………….. 1 3. Early Inaction Against COVID-19………………………….. 5 4. Policy Response to the First Wave………………………… 10 5. Hubris and Political Avarice………………………………… 18 6. Ignoring the Signs and the Science………………………... 27 7. Unforgivable Negligence…………………………..…………. 41 8. Vaccine Mismanagement..……………………………...…… 51 9. Wider Impact of Policy Failures…………………………….. 82 10. The Way Ahead……………………………………………….. 89 11. Annexure 1. Indian National Congress: Compendium of Statements, Letters and Resolutions on COVID-19 (March 2020 - June 2021)…………………………………… A1 Executive Summary The mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic has been independent India’s gravest governance failure. The Union government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi did not take adequate measures to prevent and contain the pandemic. Therefore, there is a Need for a White Paper (Chapter-1) that examines the government’s acts of omission and commission, its impact on India and suggests constructive measures to improve policy responses to the current and future waves of the pandemic. The Modi government’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis began with its Early Inaction in January 2020 (detailed in Chapter-2). The government ignored early warnings from experts and political leaders from the Opposition. It failed to learn from the lessons and response models of other countries which had been hit by the pandemic. It did not scale up nationwide the lessons from Kerala’s experience in successfully suppressing a virus outbreak (the Nipah virus). -

Indian National Congress Sessions

Indian National Congress Sessions INC sessions led the course of many national movements as well as reforms in India. Consequently, the resolutions passed in the INC sessions reflected in the political reforms brought about by the British government in India. Although the INC went through a major split in 1907, its leaders reconciled on their differences soon after to give shape to the emerging face of Independent India. Here is a list of all the Indian National Congress sessions along with important facts about them. This list will help you prepare better for SBI PO, SBI Clerk, IBPS Clerk, IBPS PO, etc. Indian National Congress Sessions During the British rule in India, the Indian National Congress (INC) became a shiny ray of hope for Indians. It instantly overshadowed all the other political associations established prior to it with its very first meeting. Gradually, Indians from all walks of life joined the INC, therefore making it the biggest political organization of its time. Most exam Boards consider the Indian National Congress Sessions extremely noteworthy. This is mainly because these sessions played a great role in laying down the foundational stone of Indian polity. Given below is the list of Indian National Congress Sessions in chronological order. Apart from the locations of various sessions, make sure you also note important facts pertaining to them. Indian National Congress Sessions Post Liberalization Era (1990-2018) Session Place Date President 1 | P a g e 84th AICC Plenary New Delhi Mar. 18-18, Shri Rahul Session 2018 Gandhi Chintan Shivir Jaipur Jan. 18-19, Smt.