My Embodied Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

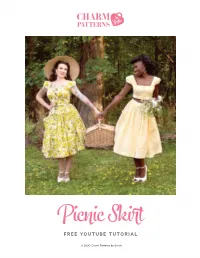

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL © 2020 Charm Patterns by Gertie SEWING INSTRUCTIONS NOTES: This style can be made for any size child or adult, as long as you know the waist measurement, how long you want the skirt, and how full you want the skirt. I used 4 yards of width, which results in a big, full skirt with lots of gathers packed in. You can easily use a shorter yardage of fabric if you prefer fewer gathers or you’re making the skirt for a smaller person or child. Seam Finishing: all raw edges are fully enclosed in the construction process, so there is no need for seam finishing. Make a vintage-inspired button-front skirt without 5/8-inch (in) (1.5 cm) seam allowances are included on all pattern pieces, except a pattern! This cute design where otherwise noted. can be made for ANY size, from child to adult! Watch CUT YOUR SKIRT PIECES my YouTube tutorial to see 1. Cut the skirt rectangle: the width should be your desired fullness (mine is how it’s done. You can find 4 yards) plus 6 in for the doubled front overlap/facing. The length should be the coordinating top by your desired length, plus 6 in for the hem allowance, plus 5/8 in for the waist seam subscribing to our Patreon allowance. at www.patreon.com/ Length: 27 in. gertiesworld. (or your desired length) Length: + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance xoxo, Gertie 27 in. Cut 1 fabric (or your + desired length) ⅝ in waist seam + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance Cut 1 fabric MATERIALS + & NOTIONS ⅝ in waist seam • 4¼ yds skirt fabric (you Width: 4 yards (or your desired fullness) + 6 in for front overlap may need more or less depending on the size and Length: 27 in. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Street Stylers Nailing This Summer’S Key Trends

STYLE KIM: There’s something very CLAIRE: Polka dots don’t have Alexa Chung about this outfit. to be cutesy. Our girl proves While on paper long-sleeved, that a few choice accessories calf-length, polka-dot co-ords can turn a twee print into an sound hard to pull off, this street uber-cool look. I’ll be taking styler rocks it. The cut-out shoes tips from her styling book and and round sunglasses add the teaming dotty co-ords with right amount of edge to make chunky heels, techno shades this all so effortlessly cool. and an ice white backpack. WE ❤ YOUR STYLE Our fashion team spy the street stylers nailing this summer’s key trends Kim Pidgeon, Claire Blackmore, fashion editor deputy fashion editor KIM: If you’ve been looking for CLAIRE: Cropped jacket, double KIM: If you’re going to rock CLAIRE: Culotte jumpsuits double denim inspiration, look denim and flares all in S/S15’s one hot hue, why not make can be a tough trend to wear no further. The frayed jean dress boldest colours – this lady’s top it magenta? This wide-leg well, but with powder blue and flares combo is this season’s of the catwalk class. I love the jumpsuit has easy breezy shoes, matching sunnies and trend heaven. The emerald clashing shades and strong lines summer style written all over an arty bag, this fashionista green boxy jacket, the snake- created by the pockets and it, while the ankle-tie heels masters it. The hot pink works print lace-up heels and the hems cutting her off at different and sunnies give an injection with her pastel accessories patent bag are what make this points on the body. -

Dress Code Is a Presentation of Who We Are.” 1997-98 Grand Officers

CLOTHING GUIDELINES: MEMBERS AND ADULTS (Reviewed annually during Grand Officer Leadership; changes made as needed) Changes made by Jr. Grand Executive Committee (November 2016) “A dress code is a presentation of who we are.” 1997-98 Grand Officers One of the benefits of Rainbow is helping our members mature into beautiful, responsible young women - prepared to meet challenges with dignity, grace and poise. The following guidelines are intended to help our members make appropriate clothing choices, based on the activities they will participate in as Rainbow girls. The Clothing Guidelines will be reviewed annually by the Jr. Members of the Grand Executive Committee. Recommendations for revisions should be forwarded to the Supreme Officer prior to July 15th of each year. REGULAR MEETINGS Appropriate: Short dress, including tea-length and high-low length, or skirt and blouse or sweater or Nevada Rainbow polo shirt (tucked in) with khaki skirt or denim skirt. Vests are acceptable. Skirt length: Ideally, HEMS should not be more than three inches above the knee. Skirts, like pencil skirts that hug the body and require “adjustment” after bowing or sitting, are unacceptable. How to tell if a skirt has a Rainbow appropriate length? Try the “Length Test”, which includes: When bowing from the waist, are your undergarments visible, or do you need to hold your skirt - or shirt - down in the back? If so, it's too short for a Rainbow meeting. Ask your mother or father to stand behind you and in front of you while you bow from the waist. If she/he gasps, the outfit is not appropriate for a Rainbow meeting. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

1 Clothing Guidelines: Members And

CLOTHING GUIDELINES: MEMBERS AND ADULTS (Reviewed annually during Grand Officer Leadership; changes made as needed) “A dress code is a presentation of who we are.” 1997-98 Grand Officers One of the benefits of Rainbow is helping our members mature into beautiful, responsible young women - prepared to meet challenges with dignity, grace and poise. The following guidelines are intended to help our members make appropriate clothing choices, based on the activities they will participate in as Rainbow girls. REGULAR MEETINGS Appropriate: Short dress, including tea-length and high-lows length, or skirt and blouse or sweater or Nevada Rainbow polo shirt (tucked in) with khaki skirt or denim skirt. Vests are acceptable. Grandie shifts that resemble a short dress are acceptable; Grandie shifts that are more costume than short dress are not acceptable (except during practice). Skirt length: HEMS cannot be shorter than three inches above the knee. Skirts, like pencil skirts that hug the body and require “adjustment” after bowing or sitting, are unacceptable. How to tell if a skirt has a Rainbow appropriate length? Try the “Length Test”, which includes: When bowing from the waist, are your undergarments visible, or do you need to hold your skirt - or shirt - down in the back? If so, it's too short for a Rainbow meeting. Ask your mother or father to stand behind you and in front of you while you bow from the waist. If she/he gasps, the outfit is not appropriate for a Rainbow meeting. Please select something a little longer and/or shows less chest. Ask your mom or dad to use a tape measure to measure from the top of your knee to the bottom of your hem. -

Fashion Trends 2016

Fashion Trends 2016 U.S. & U.K. Report [email protected] Intro With every query typed into a search bar, we are given a glimpse into user considerations or intentions. By compiling top searches, we are able to render a strong representation of the population and gain insight into this population’s behavior. In our second iteration of the Google Fashion Trends Report, we are excited to introduce data from multiple markets. This report focuses on apparel trends from the United States and United Kingdom to enable a better understanding of how trends spread and behaviors emerge across the two markets. We are proud to share this iteration and look forward to hearing back from you. Olivier Zimmer | Trends Data Scientist Yarden Horwitz | Trends Brand Strategist Methodology To compile a list of accurate trends within the fashion industry, we pulled top volume queries related to the apparel category and looked at their monthly volume from May 2014 to May 2016. We first removed any seasonal effect, and then measured the year-over-year growth, velocity, and acceleration for each search query. Based on these metrics, we were able to classify the queries into similar trend patterns. We then curated the most significant trends to illustrate interesting shifts in behavior. Query Deseasonalized Trend 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 Query 2016 Characteristics Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Top Risers a Spotlight on an Extensive List and Decliners Top Trending of the Top Volume Themes Fashion Trends Trend Categories To identify top trends, we categorized past data into six different clusters based on Sustained Seasonal Rising similar behaviors. -

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother. -

ITAA 2018 Design Catalog

Design Exhibition Committees Reviews of Designs Design Review Committee Reviewers for Creative Design Submissions Review Chair: Belinda Orzada, University of Delaware First Review Catalog Chair: Review Chair: Belinda Orzada, University of Delaware Sheri L. Dragoo, Texas Woman’s University V.P. for Scholarship: ITAA Review Members Youn-Kyung Kim, University of Tennessee Lynn Boorady, SUNY Buffalo State Elizabeth Bye, University of Minnesota A total of 118 design pieces were accepted for display Melanie Carrico, University of North Carolina at Greensboro at the 2018 ITAA Design Exhibition. Submissions May Chae, Montclair State University included 122 professional submissions, 78 graduate Chanjuan Chen, Kent State University submissions, and 134 undergraduate submissions, Deborah Christiansen, Indiana University representing respective acceptance rates of 49%, 34% Bridgett Clinton-Scott, University of Maryland Eastern Shore and 29%. All jurying employed a double blind pro- Andrea Eklund, Central Washington University cess so the jurors had no indication of whose work Adriana Gorea, Syracuse University they were judging. A double-blind jury of textile and Denise Green, Cornell University apparel peers reviewed each submission including Bora Han, Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising design statement and images. Susan Hannel, University of Rhode Island Cynthia Istook, North Carolina State University Design Exhibit Committee Sandra Keiser, Mount Mary University Laura Kane, Framingham State University Eundeok Kim, Florida State University -

Sew Wow Advanced Clothing Member's Guide

SEW WOW #32009 Advanced Clothing Member’s Guide and Project Requirements This guide belongs to:_________________________________ Year:________ SEW WOW Advanced Clothing Member’s Guide and Project Requirements Contents Project Objectives Project Objectives............................................2 • Learn to enjoy and appreciate the process of clothing construction. Requirements ...................................................2 • Acquire the advanced skills needed to create Focus Areas Summary .....................................3 a garment, outfit, and/or accessories. General Resources ...........................................3 • Develop confidence through successfully Focus Area A: Active/Sportswear....................4 completing the project. Focus Area B: Outdoor Wear...........................6 • Share what you have learned with others. Focus Area C: Western Wear ...........................8 Focus Area D: Formal Wear ..........................10 Requirements Focus Area E: Embellished Apparel..............12 1. Select one project focus area that includes the clothing item(s), fabric, and construction Focus Area F: Tailored Apparel.....................14 skills you want to master. A summary of Focus Area G: Pattern Your Own..................16 focus areas is on page 3. General Advanced Activities .........................18 2. Set at least three goals to achieve in this project year. Project Summary ...........................................19 Part A: General Advanced Activity ..........19 3. Do one of the “General Advanced -

Manor Primary School Music Year 1: in the Grove Overview of the Learning: All the Learning Is Focused Around One Song: in the Groove

Manor Primary School Music Year 1: In The Grove Overview of the Learning: All the learning is focused around one song: In The Groove. The material presents an integrated approach to music where games, the interrelated dimensions of music (pulse, rhythm, pitch etc.), singing and playing instruments are all linked. Core Aims Pupils should be taught How to listen to music. perform, listen to, review and evaluate music across a range of historical periods, genres, styles and To sing a range of songs song. traditions, including the works of the great composers and musicians To understand the geographical origin of the music and in which era it was composed. Learn to sing and to use their voices, to create and compose music on their own and with others, To experience and learn how to apply key musical concepts/elements, eg finding a pulse, clapping have the opportunity to learn a musical instrument, use technology appropriately and have the a rhythm, use of pitch. opportunity to progress to the next level of musical excellence To play the accompanying instrumental parts (optional). understand and explore how music is created, produced and communicated, including through the inter-related dimensions: pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure and To work together in a band/ensemble. appropriate musical notations. To develop creativity through improvising and composing within the song. To understand and use the first five notes of C Major scale while improvising and composing. To experience links to other areas of the curriculum To recognise the style of the music and to understand its main style indicators.