Chapter 15 Rotation Dynamics: Definitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Euler Angles 1

Welcome Guest View Cart (0 items) Login Home Products Support News About Us Understanding Euler Angles 1. Introduction Attitude and Heading Sensors from CH Robotics can provide orientation information using both Euler Angles and Quaternions. Compared to quaternions, Euler Angles are simple and intuitive and they lend themselves well to simple analysis and control. On the other hand, Euler Angles are limited by a phenomenon called "Gimbal Lock," which we will investigate in more detail later. In applications where the sensor will never operate near pitch angles of +/‐ 90 degrees, Euler Angles are a good choice. Sensors from CH Robotics that can provide Euler Angle outputs include the GP9 GPS‐Aided AHRS, and the UM7 Orientation Sensor. Figure 1 ‐ The Inertial Frame Euler angles provide a way to represent the 3D orientation of an object using a combination of three rotations about different axes. For convenience, we use multiple coordinate frames to describe the orientation of the sensor, including the "inertial frame," the "vehicle‐1 frame," the "vehicle‐2 frame," and the "body frame." The inertial frame axes are Earth‐fixed, and the body frame axes are aligned with the sensor. The vehicle‐1 and vehicle‐2 are intermediary frames used for convenience when illustrating the sequence of operations that take us from the inertial frame to the body frame of the sensor. It may seem unnecessarily complicated to use four different coordinate frames to describe the orientation of the sensor, but the motivation for doing so will become clear as we proceed. For clarity, this application note assumes that the sensor is mounted to an aircraft. -

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

The Rolling Ball Problem on the Sphere

S˜ao Paulo Journal of Mathematical Sciences 6, 2 (2012), 145–154 The rolling ball problem on the sphere Laura M. O. Biscolla Universidade Paulista Rua Dr. Bacelar, 1212, CEP 04026–002 S˜aoPaulo, Brasil Universidade S˜aoJudas Tadeu Rua Taquari, 546, CEP 03166–000, S˜aoPaulo, Brasil E-mail address: [email protected] Jaume Llibre Departament de Matem`atiques, Universitat Aut`onomade Barcelona 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain E-mail address: [email protected] Waldyr M. Oliva CAMGSD, LARSYS, Instituto Superior T´ecnico, UTL Av. Rovisco Pais, 1049–0011, Lisbon, Portugal Departamento de Matem´atica Aplicada Instituto de Matem´atica e Estat´ıstica, USP Rua do Mat˜ao,1010–CEP 05508–900, S˜aoPaulo, Brasil E-mail address: [email protected] Dedicated to Lu´ıs Magalh˜aes and Carlos Rocha on the occasion of their 60th birthdays Abstract. By a sequence of rolling motions without slipping or twist- ing along arcs of great circles outside the surface of a sphere of radius R, a spherical ball of unit radius has to be transferred from an initial state to an arbitrary final state taking into account the orientation of the ball. Assuming R > 1 we provide a new and shorter prove of the result of Frenkel and Garcia in [4] that with at most 4 moves we can go from a given initial state to an arbitrary final state. Important cases such as the so called elimination of the spin discrepancy are done with 3 moves only. 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 58E25, 93B27. Key words: Control theory, rolling ball problem. -

PHYSICS of ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3

Chapter 2 PHYSICS OF ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3 1 Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA 2 NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA 3 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Toulouse, France This chapter discusses potential technologies for achieving artificial gravity in a space vehicle. We begin with a series of definitions and a general description of the rotational dynamics behind the forces ultimately exerted on the human body during centrifugation, such as gravity level, gravity gradient, and Coriolis force. Human factors considerations and comfort limits associated with a rotating environment are then discussed. Finally, engineering options for designing space vehicles with artificial gravity are presented. Figure 2-01. Artist's concept of one of NASA early (1962) concepts for a manned space station with artificial gravity: a self- inflating 22-m-diameter rotating hexagon. Photo courtesy of NASA. 1 ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY: WHAT IS IT? 1.1 Definition Artificial gravity is defined in this book as the simulation of gravitational forces aboard a space vehicle in free fall (in orbit) or in transit to another planet. Throughout this book, the term artificial gravity is reserved for a spinning spacecraft or a centrifuge within the spacecraft such that a gravity-like force results. One should understand that artificial gravity is not gravity at all. Rather, it is an inertial force that is indistinguishable from normal gravity experience on Earth in terms of its action on any mass. A centrifugal force proportional to the mass that is being accelerated centripetally in a rotating device is experienced rather than a gravitational pull. -

Simple Harmonic Motion

[SHIVOK SP211] October 30, 2015 CH 15 Simple Harmonic Motion I. Oscillatory motion A. Motion which is periodic in time, that is, motion that repeats itself in time. B. Examples: 1. Power line oscillates when the wind blows past it 2. Earthquake oscillations move buildings C. Sometimes the oscillations are so severe, that the system exhibiting oscillations break apart. 1. Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse "Gallopin' Gertie" a) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j‐zczJXSxnw II. Simple Harmonic Motion A. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__2YND93ofE Watch the video in your spare time. This professor is my teaching Idol. B. In the figure below snapshots of a simple oscillatory system is shown. A particle repeatedly moves back and forth about the point x=0. Page 1 [SHIVOK SP211] October 30, 2015 C. The time taken for one complete oscillation is the period, T. In the time of one T, the system travels from x=+x , to –x , and then back to m m its original position x . m D. The velocity vector arrows are scaled to indicate the magnitude of the speed of the system at different times. At x=±x , the velocity is m zero. E. Frequency of oscillation is the number of oscillations that are completed in each second. 1. The symbol for frequency is f, and the SI unit is the hertz (abbreviated as Hz). 2. It follows that F. Any motion that repeats itself is periodic or harmonic. G. If the motion is a sinusoidal function of time, it is called simple harmonic motion (SHM). -

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples Example 1 Determine the angular displacement in radians of 6.5 revolutions. Round to the nearest tenth. Each revolution equals 2 radians. For 6.5 revolutions, the number of radians is 6.5 2 or 13 . 13 radians equals about 40.8 radians. Example 2 Determine the angular velocity if 4.8 revolutions are completed in 4 seconds. Round to the nearest tenth. The angular displacement is 4.8 2 or 9.6 radians. = t 9.6 = = 9.6 , t = 4 4 7.539822369 Use a calculator. The angular velocity is about 7.5 radians per second. Example 3 AMUSEMENT PARK Jack climbs on a horse that is 12 feet from the center of a merry-go-round. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 rotations per minute. Determine Jack’s angular velocity in radians 4 per second. Round to the nearest hundredth. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 or 3.25 revolutions per minute. Convert revolutions per minute to radians 4 per second. 3.25 revolutions 1 minute 2 radians 0.3403392041 radian per second 1 minute 60 seconds 1 revolution Jack has an angular velocity of about 0.34 radian per second. Example 4 Determine the linear velocity of a point rotating at an angular velocity of 12 radians per second at a distance of 8 centimeters from the center of the rotating object. Round to the nearest tenth. v = r v = (8)(12 ) r = 8, = 12 v 301.5928947 Use a calculator. The linear velocity is about 301.6 centimeters per second. -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

Euler Quaternions

Four different ways to represent rotation my head is spinning... The space of rotations SO( 3) = {R ∈ R3×3 | RRT = I,det(R) = +1} Special orthogonal group(3): Why det( R ) = ± 1 ? − = − Rotations preserve distance: Rp1 Rp2 p1 p2 Rotations preserve orientation: ( ) × ( ) = ( × ) Rp1 Rp2 R p1 p2 The space of rotations SO( 3) = {R ∈ R3×3 | RRT = I,det(R) = +1} Special orthogonal group(3): Why it’s a group: • Closed under multiplication: if ∈ ( ) then ∈ ( ) R1, R2 SO 3 R1R2 SO 3 • Has an identity: ∃ ∈ ( ) = I SO 3 s.t. IR1 R1 • Has a unique inverse… • Is associative… Why orthogonal: • vectors in matrix are orthogonal Why it’s special: det( R ) = + 1 , NOT det(R) = ±1 Right hand coordinate system Possible rotation representations You need at least three numbers to represent an arbitrary rotation in SO(3) (Euler theorem). Some three-number representations: • ZYZ Euler angles • ZYX Euler angles (roll, pitch, yaw) • Axis angle One four-number representation: • quaternions ZYZ Euler Angles φ = θ rzyz ψ φ − φ cos sin 0 To get from A to B: φ = φ φ Rz ( ) sin cos 0 1. Rotate φ about z axis 0 0 1 θ θ 2. Then rotate θ about y axis cos 0 sin θ = ψ Ry ( ) 0 1 0 3. Then rotate about z axis − sinθ 0 cosθ ψ − ψ cos sin 0 ψ = ψ ψ Rz ( ) sin cos 0 0 0 1 ZYZ Euler Angles φ θ ψ Remember that R z ( ) R y ( ) R z ( ) encode the desired rotation in the pre- rotation reference frame: φ = pre−rotation Rz ( ) Rpost−rotation Therefore, the sequence of rotations is concatentated as follows: (φ θ ψ ) = φ θ ψ Rzyz , , Rz ( )Ry ( )Rz ( ) φ − φ θ θ ψ − ψ cos sin 0 cos 0 sin cos sin 0 (φ θ ψ ) = φ φ ψ ψ Rzyz , , sin cos 0 0 1 0 sin cos 0 0 0 1− sinθ 0 cosθ 0 0 1 − − − cφ cθ cψ sφ sψ cφ cθ sψ sφ cψ cφ sθ (φ θ ψ ) = + − + Rzyz , , sφ cθ cψ cφ sψ sφ cθ sψ cφ cψ sφ sθ − sθ cψ sθ sψ cθ ZYX Euler Angles (roll, pitch, yaw) φ − φ cos sin 0 To get from A to B: φ = φ φ Rz ( ) sin cos 0 1. -

Theory of Angular Momentum and Spin

Chapter 5 Theory of Angular Momentum and Spin Rotational symmetry transformations, the group SO(3) of the associated rotation matrices and the 1 corresponding transformation matrices of spin{ 2 states forming the group SU(2) occupy a very important position in physics. The reason is that these transformations and groups are closely tied to the properties of elementary particles, the building blocks of matter, but also to the properties of composite systems. Examples of the latter with particularly simple transformation properties are closed shell atoms, e.g., helium, neon, argon, the magic number nuclei like carbon, or the proton and the neutron made up of three quarks, all composite systems which appear spherical as far as their charge distribution is concerned. In this section we want to investigate how elementary and composite systems are described. To develop a systematic description of rotational properties of composite quantum systems the consideration of rotational transformations is the best starting point. As an illustration we will consider first rotational transformations acting on vectors ~r in 3-dimensional space, i.e., ~r R3, 2 we will then consider transformations of wavefunctions (~r) of single particles in R3, and finally N transformations of products of wavefunctions like j(~rj) which represent a system of N (spin- Qj=1 zero) particles in R3. We will also review below the well-known fact that spin states under rotations behave essentially identical to angular momentum states, i.e., we will find that the algebraic properties of operators governing spatial and spin rotation are identical and that the results derived for products of angular momentum states can be applied to products of spin states or a combination of angular momentum and spin states. -

The Spin, the Nutation and the Precession of the Earth's Axis Revisited

The spin, the nutation and the precession of the Earth’s axis revisited The spin, the nutation and the precession of the Earth’s axis revisited: A (numerical) mechanics perspective W. H. M¨uller [email protected] Abstract Mechanical models describing the motion of the Earth’s axis, i.e., its spin, nutation and its precession, have been presented for more than 400 years. Newton himself treated the problem of the precession of the Earth, a.k.a. the precession of the equinoxes, in Liber III, Propositio XXXIX of his Principia [1]. He decomposes the duration of the full precession into a part due to the Sun and another part due to the Moon, to predict a total duration of 26,918 years. This agrees fairly well with the experimentally observed value. However, Newton does not really provide a concise rational derivation of his result. This task was left to Chandrasekhar in Chapter 26 of his annotations to Newton’s book [2] starting from Euler’s equations for the gyroscope and calculating the torques due to the Sun and to the Moon on a tilted spheroidal Earth. These differential equations can be solved approximately in an analytic fashion, yielding Newton’s result. However, they can also be treated numerically by using a Runge-Kutta approach allowing for a study of their general non-linear behavior. This paper will show how and explore the intricacies of the numerical solution. When solving the Euler equations for the aforementioned case numerically it shows that besides the precessional movement of the Earth’s axis there is also a nu- tation present. -

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

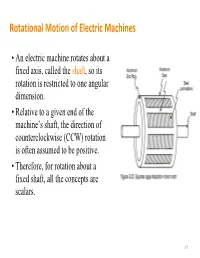

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

Thomas Precession Is the Basis for the Structure of Matter and Space Preston Guynn

Thomas Precession is the Basis for the Structure of Matter and Space Preston Guynn To cite this version: Preston Guynn. Thomas Precession is the Basis for the Structure of Matter and Space. 2018. hal- 02628032 HAL Id: hal-02628032 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02628032 Submitted on 26 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thomas Precession is the Basis for the Structure of Matter and Space Einstein's theory of special relativity was incomplete as originally formulated since it did not include the rotational effect described twenty years later by Thomas, now referred to as Thomas precession. Though Thomas precession has been accepted for decades, its relationship to particle structure is a recent discovery, first described in an article titled "Electromagnetic effects and structure of particles due to special relativity". Thomas precession acts as a velocity dependent counter-rotation, so that at a rotation velocity of 3 / 2 c , precession is equal to rotation, resulting in an inertial frame of reference. During the last year and a half significant progress was made in determining further details of the role of Thomas precession in particle structure, fundamental constants, and the galactic rotation velocity.