Basic Pipelining and Simple RISC Processors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADSP-21065L SHARC User's Manual; Chapter 2, Computation

&20387$7,2181,76 Figure 2-0. Table 2-0. Listing 2-0. The processor’s computation units provide the numeric processing power for performing DSP algorithms, performing operations on both fixed-point and floating-point numbers. Each computation unit executes instructions in a single cycle. The processor contains three computation units: • An arithmetic/logic unit (ALU) Performs a standard set of arithmetic and logic operations in both fixed-point and floating-point formats. • A multiplier Performs floating-point and fixed-point multiplication as well as fixed-point dual multiply/add or multiply/subtract operations. •A shifter Performs logical and arithmetic shifts, bit manipulation, field deposit and extraction operations on 32-bit operands and can derive exponents as well. ADSP-21065L SHARC User’s Manual 2-1 PM Data Bus DM Data Bus Register File Multiplier Shifter ALU 16 × 40-bit MR2 MR1 MR0 Figure 2-1. Computation units block diagram The computation units are architecturally arranged in parallel, as shown in Figure 2-1. The output from any computation unit can be input to any computation unit on the next cycle. The computation units store input operands and results locally in a ten-port register file. The Register File is accessible to the processor’s pro- gram memory data (PMD) bus and its data memory data (DMD) bus. Both of these buses transfer data between the computation units and internal memory, external memory, or other parts of the processor. This chapter covers these topics: • Data formats • Register File data storage and transfers -

Configurable RISC-V Softcore Processor for FPGA Implementation

1 Configurable RISC-V softcore processor for FPGA implementation Joao˜ Filipe Monteiro Rodrigues, Instituto Superior Tecnico,´ Universidade de Lisboa Abstract—Over the past years, the processor market has and development of several programming tools. The RISC-V been dominated by proprietary architectures that implement Foundation controls the RISC-V evolution, and its members instruction sets that require licensing and the payment of fees to are responsible for promoting the adoption of RISC-V and receive permission so they can be used. ARM is an example of one of those companies that sell its microarchitectures to participating in the development of the new ISA. In the list of the manufactures so they can implement them into their own members are big companies like Google, NVIDIA, Western products, and it does not allow the use of its instruction set Digital, Samsung, or Qualcomm. (ISA) in other implementations without licensing. The RISC-V The main goal of this work is the development of a RISC- instruction set appeared proposing the hardware and software V softcore processor to be implemented in an FPGA, using development without costs, through the creation of an open- source ISA. This way, it is possible that any project that im- a non-RISC-V core as the base of this architecture. The plements the RISC-V ISA can be made available open-source or proposed solution is focused on solving the problems and even implemented in commercial products. However, the RISC- limitations identified in the other RISC-V cores that were V solutions that have been developed do not present the needed analyzed in this thesis, especially in terms of the adaptability requirements so they can be included in projects, especially the and flexibility, allowing future modifications according to the research projects, because they offer poor documentation, and their performances are not suitable. -

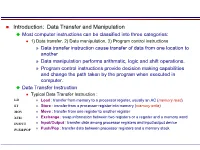

Most Computer Instructions Can Be Classified Into Three Categories

Introduction: Data Transfer and Manipulation Most computer instructions can be classified into three categories: 1) Data transfer, 2) Data manipulation, 3) Program control instructions » Data transfer instruction cause transfer of data from one location to another » Data manipulation performs arithmatic, logic and shift operations. » Program control instructions provide decision making capabilities and change the path taken by the program when executed in computer. Data Transfer Instruction Typical Data Transfer Instruction : LD » Load : transfer from memory to a processor register, usually an AC (memory read) ST » Store : transfer from a processor register into memory (memory write) MOV » Move : transfer from one register to another register XCH » Exchange : swap information between two registers or a register and a memory word IN/OUT » Input/Output : transfer data among processor registers and input/output device PUSH/POP » Push/Pop : transfer data between processor registers and a memory stack MODE ASSEMBLY REGISTER TRANSFER CONVENTION Direct Address LD ADR ACM[ADR] Indirect Address LD @ADR ACM[M[ADR]] Relative Address LD $ADR ACM[PC+ADR] Immediate Address LD #NBR ACNBR Index Address LD ADR(X) ACM[ADR+XR] Register LD R1 ACR1 Register Indirect LD (R1) ACM[R1] Autoincrement LD (R1)+ ACM[R1], R1R1+1 8 Addressing Mode for the LOAD Instruction Data Manipulation Instruction 1) Arithmetic, 2) Logical and bit manipulation, 3) Shift Instruction Arithmetic Instructions : NAME MNEMONIC Increment INC Decrement DEC Add ADD Subtract SUB Multiply -

Unit – I Computer Architecture and Operating System – Scs1315

SCHOOL OF ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMMMUNICATION ENGINEERING UNIT – I COMPUTER ARCHITECTURE AND OPERATING SYSTEM – SCS1315 UNIT.1 INTRODUCTION Central Processing Unit - Introduction - General Register Organization - Stack organization -- Basic computer Organization - Computer Registers - Computer Instructions - Instruction Cycle. Arithmetic, Logic, Shift Microoperations- Arithmetic Logic Shift Unit -Example Architectures: MIPS, Power PC, RISC, CISC Central Processing Unit The part of the computer that performs the bulk of data-processing operations is called the central processing unit CPU. The CPU is made up of three major parts, as shown in Fig.1 Fig 1. Major components of CPU. The register set stores intermediate data used during the execution of the instructions. The arithmetic logic unit (ALU) performs the required microoperations for executing the instructions. The control unit supervises the transfer of information among the registers and instructs the ALU as to which operation to perform. General Register Organization When a large number of registers are included in the CPU, it is most efficient to connect them through a common bus system. The registers communicate with each other not only for direct data transfers, but also while performing various microoperations. Hence it is necessary to provide a common unit that can perform all the arithmetic, logic, and shift microoperations in the processor. A bus organization for seven CPU registers is shown in Fig.2. The output of each register is connected to two multiplexers (MUX) to form the two buses A and B. The selection lines in each multiplexer select one register or the input data for the particular bus. The A and B buses form the inputs to a common arithmetic logic unit (ALU). -

S.D.M COLLEGE of ENGINEERING and TECHNOLOGY Sridhar Y

VISVESVARAYA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY S.D.M COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY A seminar report on CUDA Submitted by Sridhar Y 2sd06cs108 8th semester DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING 2009-10 Page 1 VISVESVARAYA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY S.D.M COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING CERTIFICATE Certified that the seminar work entitled “CUDA” is a bonafide work presented by Sridhar Y bearing USN 2SD06CS108 in a partial fulfillment for the award of degree of Bachelor of Engineering in Computer Science Engineering of the Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belgaum during the year 2009-10. The seminar report has been approved as it satisfies the academic requirements with respect to seminar work presented for the Bachelor of Engineering Degree. Staff in charge H.O.D CSE Name: Sridhar Y USN: 2SD06CS108 Page 2 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Evolution of GPU programming and CUDA 5 3. CUDA Structure for parallel processing 9 4. Programming model of CUDA 10 5. Portability and Security of the code 12 6. Managing Threads with CUDA 14 7. Elimination of Deadlocks in CUDA 17 8. Data distribution among the Thread Processes in CUDA 14 9. Challenges in CUDA for the Developers 19 10. The Pros and Cons of CUDA 19 11. Conclusions 21 Bibliography 21 Page 3 Abstract Parallel processing on multi core processors is the industry’s biggest software challenge, but the real problem is there are too many solutions. One of them is Nvidia’s Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA), a software platform for massively parallel high performance computing on the powerful Graphics Processing Units (GPUs). -

Computer Architecture Research with RISC-‐V

Computer Architecture Research with RISC-V Krste Asanovic UC Berkeley, RISC-V Foundaon, & SiFive Inc. [email protected] www.riscv.org CARRV, Boston, MA October 14, 2017 Only Two Big Mistakes Possible when Picking Research ISA § Design your own § Use someone else’s Promise of using commercially popular ISAs for research § Ported applicaons/workloads to study § Standard soRware stacks (compilers, OS) § Real commercial hardware to experiment with § Real commercial hardware to validate models with § ExisAng implementaons to study / modify § Industry is more interested in your results 3 Types of projects and standard ISAs used by me or my group in last 30 years § Experiments on real hardware plaorms: - Transputer arrays, SPARC workstaons, MIPS workstaons, POWER workstaons, ARMv7 handhelds, x86 desktops/ servers § Research chips built around modified MIPS ISA: - T0, IRAM, STC1, Scale, Maven § FPGA prototypes/simulaons using various ISAs: - RAMP Blue (modified Microblaze), RAMP Gold/ DIABLO (SPARC v8) § Experiments using soRware architectural simulators: - SimpleScalar (PISA), SMTsim (Alpha), Simics (SPARC,x86), Bochs (x86), MARSS (x86), Gem5(SPARC), PIN (Itanium, x86), … § And of course, other groups used some others too. RealiMes of using standard ISAs § Everything only works if you don’t change anything - Stock binary applicaons - Stock libraries - Stock compiler - Stock OS - Stock hardware implementaon § Add a new instrucAon, get a new non-standard ISA! - Need source code for the apps and recompile - Impossible for most real interesAng applicaons -

Lecture 6: Instruction Set Architecture and the 80X86

Lecture 6: Instruction Set Architecture and the 80x86 Professor Randy H. Katz Computer Science 252 Spring 1996 RHK.S96 1 Review From Last Time • Given sales a function of performance relative to competition, tremendous investment in improving product as reported by performance summary • Good products created when have: – Good benchmarks – Good ways to summarize performance • If not good benchmarks and summary, then choice between improving product for real programs vs. improving product to get more sales=> sales almost always wins • Time is the measure of computer performance! • What about cost? RHK.S96 2 Review: Integrated Circuits Costs IC cost = Die cost + Testing cost + Packaging cost Final test yield Die cost = Wafer cost Dies per Wafer * Die yield Dies per wafer = p * ( Wafer_diam / 2)2 – p * Wafer_diam – Test dies Die Area Ö 2 * Die Area Defects_per_unit_area * Die_Area Die Yield = Wafer yield * { 1 + } 4 Die Cost is goes roughly with area RHK.S96 3 Review From Last Time Price vs. Cost 100% 80% Average Discount 60% Gross Margin 40% Direct Costs 20% Component Costs 0% Mini W/S PC 5 4.7 3.8 4 3.5 Average Discount 3 2.5 Gross Margin 2 1.8 Direct Costs 1.5 1 Component Costs 0 Mini W/S PC RHK.S96 4 Today: Instruction Set Architecture • 1950s to 1960s: Computer Architecture Course Computer Arithmetic • 1970 to mid 1980s: Computer Architecture Course Instruction Set Design, especially ISA appropriate for compilers • 1990s: Computer Architecture Course Design of CPU, memory system, I/O system, Multiprocessors RHK.S96 5 Computer Architecture? . the attributes of a [computing] system as seen by the programmer, i.e. -

Low-Power Microprocessor Based on Stack Architecture

Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Stack on based Microprocessor Low-power Master’s Thesis Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Series of Master’s theses Department of Electrical and Information Technology LU/LTH-EIT 2015-464 Department of Electrical and Information Technology, http://www.eit.lth.se Faculty of Engineering, LTH, Lund University, September 2015. Department of Electrical and Information Technology Master of Science Thesis Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Supervisors: Author: Prof. Joachim Rodrigues Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Prof. Anders Ard¨o Lund 2015 © The Department of Electrical and Information Technology Lund University Box 118, S-221 00 LUND SWEDEN This thesis is set in Computer Modern 10pt, with the LATEX Documentation System ©Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao 2015 Printed in E-huset Lund, Sweden. Sep. 2015 Abstract There are many applications of microprocessors in embedded applications, where power efficiency becomes a critical requirement, e.g. wearable or mobile devices in healthcare, space instrumentation and handheld devices. One of the methods of achieving low power operation is by simplifying the device architecture. RISC/CISC processors consume considerable power because of their complexity, which is due to their multiplexer system connecting the register file to the func- tional units and their instruction pipeline system. On the other hand, the Stack machines are comparatively less complex due to their implied addressing to the top two registers of the stack and smaller operation codes. This makes the instruction and the address decoder circuit simple by eliminating the multiplex switches for read and write ports of the register file. -

The Central Processor Unit

Systems Architecture The Central Processing Unit The Central Processing Unit – p. 1/11 The Computer System Application High-level Language Operating System Assembly Language Machine level Microprogram Digital logic Hardware / Software Interface The Central Processing Unit – p. 2/11 CPU Structure External Memory MAR: Memory MBR: Memory Address Register Buffer Register Address Incrementer R15 / PC R11 R7 R3 R14 / LR R10 R6 R2 R13 / SP R9 R5 R1 R12 R8 R4 R0 User Registers Booth’s Multiplier Barrel IR Shifter Control Unit CPSR 32-Bit ALU The Central Processing Unit – p. 3/11 CPU Registers Internal Registers Condition Flags PC Program Counter C Carry IR Instruction Register Z Zero MAR Memory Address Register N Negative MBR Memory Buffer Register V Overflow CPSR Current Processor Status Register Internal Devices User Registers ALU Arithmetic Logic Unit Rn Register n CU Control Unit n = 0 . 15 M Memory Store SP Stack Pointer MMU Mem Management Unit LR Link Register Note that each CPU has a different set of User Registers The Central Processing Unit – p. 4/11 Current Process Status Register • Holds a number of status flags: N True if result of last operation is Negative Z True if result of last operation was Zero or equal C True if an unsigned borrow (Carry over) occurred Value of last bit shifted V True if a signed borrow (oVerflow) occurred • Current execution mode: User Normal “user” program execution mode System Privileged operating system tasks Some operations can only be preformed in a System mode The Central Processing Unit – p. 5/11 Register Transfer Language NAME Value of register or unit ← Transfer of data MAR ← PC x: Guard, only if x true hcci: MAR ← PC (field) Specific field of unit ALU(C) ← 1 (name), bit (n) or range (n:m) R0 ← MBR(0:7) Rn User Register n R0 ← MBR num Decimal number R0 ← 128 2_num Binary number R1 ← 2_0100 0001 0xnum Hexadecimal number R2 ← 0x40 M(addr) Memory Access (addr) MBR ← M(MAR) IR(field) Specified field of IR CU ← IR(op-code) ALU(field) Specified field of the ALU(C) ← 1 Arithmetic and Logic Unit The Central Processing Unit – p. -

X86-64 Machine-Level Programming∗

x86-64 Machine-Level Programming∗ Randal E. Bryant David R. O'Hallaron September 9, 2005 Intel’s IA32 instruction set architecture (ISA), colloquially known as “x86”, is the dominant instruction format for the world’s computers. IA32 is the platform of choice for most Windows and Linux machines. The ISA we use today was defined in 1985 with the introduction of the i386 microprocessor, extending the 16-bit instruction set defined by the original 8086 to 32 bits. Even though subsequent processor generations have introduced new instruction types and formats, many compilers, including GCC, have avoided using these features in the interest of maintaining backward compatibility. A shift is underway to a 64-bit version of the Intel instruction set. Originally developed by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and named x86-64, it is now supported by high end processors from AMD (who now call it AMD64) and by Intel, who refer to it as EM64T. Most people still refer to it as “x86-64,” and we follow this convention. Newer versions of Linux and GCC support this extension. In making this switch, the developers of GCC saw an opportunity to also make use of some of the instruction-set features that had been added in more recent generations of IA32 processors. This combination of new hardware and revised compiler makes x86-64 code substantially different in form and in performance than IA32 code. In creating the 64-bit extension, the AMD engineers also adopted some of the features found in reduced-instruction set computers (RISC) [7] that made them the favored targets for optimizing compilers. -

Instruction Set Architecture

The Instruction Set Architecture Application Instruction Set Architecture OiOperating Compiler System Instruction Set Architecture Instr. Set Proc. I/O system or Digital Design “How to talk to computers if Circuit Design you aren’t on Star Trek” CSE 240A Dean Tullsen CSE 240A Dean Tullsen How to Sppmpeak Computer Crafting an ISA High Level Language temp = v[k]; • Designing an ISA is both an art and a science Program v[k] = v[k+ 1]; v[k+1] = temp; • ISA design involves dealing in an extremely rare resource Compiler – instruction bits! lw $15, 0($2) AblLAssembly Language lw $16, 4($2) • Some things we want out of our ISA Program sw $16, 0($2) – completeness sw $15, 4($2) Assembler – orthogonality 1000110001100010000000000000000 – regularity and simplicity Machine Language 1000110011110010000000000000100 – compactness Program 1010110011110010000000000000000 – ease of ppgrogramming 1010110001100010000000000000100 Machine Interpretation – ease of implementation Control Signal Spec ALUOP[0:3] <= InstReg[9:11] & MASK CSE 240A Dean Tullsen CSE 240A Dean Tullsen Where are the instructions? KKyey ISA decisions • Harvard architecture • Von Neumann architecture destination operand operation • operations y = x + b – how many? inst & source operands inst cpu data – which ones storage storage operands cpu • data “stored-program” computer – how many? storage – location – types – how to specify? how does the computer know what L1 • instruction format 0001 0100 1101 1111 inst – size means? cache L2 cpu Mem cache – how many formats? L1 dtdata cache CSE -

RISC-V Geneology

RISC-V Geneology Tony Chen David A. Patterson Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California at Berkeley Technical Report No. UCB/EECS-2016-6 http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2016/EECS-2016-6.html January 24, 2016 Copyright © 2016, by the author(s). All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission. Introduction RISC-V is an open instruction set designed along RISC principles developed originally at UC Berkeley1 and is now set to become an open industry standard under the governance of the RISC-V Foundation (www.riscv.org). Since the instruction set architecture (ISA) is unrestricted, organizations can share implementations as well as open source compilers and operating systems. Designed for use in custom systems on a chip, RISC-V consists of a base set of instructions called RV32I along with optional extensions for multiply and divide (RV32M), atomic operations (RV32A), single-precision floating point (RV32F), and double-precision floating point (RV32D). The base and these four extensions are collectively called RV32G. This report discusses the historical precedents of RV32G. We look at 18 prior instruction set architectures, chosen primarily from earlier UC Berkeley RISC architectures and major proprietary RISC instruction sets. Among the 122 instructions in RV32G: ● 6 instructions do not have precedents among the selected instruction sets, ● 98 instructions of the 116 with precedents appear in at least three different instruction sets.