Professional Athletes-Held to a Higher Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxed out of The

BOXED OUT OF THE NBA REMEMBERING THE EASTERN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL LEAGUE BY SYL SOBEL AND JAY ROSENSTEIN “Syl and Jay brought me back to my brief playing days in the Eastern League! The small towns, the tiny gyms, the rabid fans, the colorful owners, and most of all the seriously good players who played with an edge because they fell one step short of the NBA. All the characters, the stories, and the brutally tough competition – it’s all here. About time the Eastern League got some love!”— Charley Rosen, author, basketball commentator, and former Eastern League player and CBA coach In Boxed out of the NBA: Remembering the Eastern Professional Basketball League, Syl Sobel and Jay Rosenstein tell the fascinating story of a league that was a pro basketball institution for over 30 years, showcasing top players from around the country. During the early years of professional basketball, the Eastern League was the next-best professional league in the world after the NBA. It was home to big-name players such as Sherman White, Jack Molinas, and Bill Spivey, who were implicated in college gambling scandals in the 1950s and were barred from the NBA, and top Black players such as Hal “King” Lear, Julius McCoy, and Wally Choice, who could not make the NBA into the early 1960s due to unwritten team quotas on African-American players. Featuring interviews with some 40 former Eastern League coaches, referees, fans, and players—including Syracuse University coach Jim Boeheim, former Temple University coach John Chaney, former Detroit Pistons player and coach Ray Scott, former NBA coach and ESPN analyst Hubie Brown, and former NBA player and coach Bob Weiss—this book provides an intimate, first-hand account of small-town professional basketball at its best. -

Salvation Army Annual Luncheon Sponsor Flyer

DOING THE MOST GOOD PRESENTS THE SALVATION ARMY 2015 ANNUAL LUNCHEON with EMMITT SMITH Hosted by: TUESDAY May 12, 2015 11:30AM University of the Incarnate Word Emmitt Smith is one of the greatest to ever play the game of football and his quest to break the NFL all- Stanley and Sandra Rosenberg Sky Room time rushing record started with a 70-yard touchdown SPECIAL VIP MEET & GREET AT 11:15 AM run from scrimmage on the very rst play of his very rst game in organized football back in 1977. As quarterback for The Salvation Army Mini-Mites in Pensacola, Florida, at the age of 8, Emmitt took the snap and ran straight up the middle for the score. As the National Football League's all-time leading rusher, the former Dallas Cowboy amassed 18,355 career rushing yards during his famed career and is also the all-time rushing touchdown record holder with 164 career rushing TDs. His impressive resume includes three Super Bowl rings and induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2010. He was the league MVP in 1993, MVP of Super Bowl XXVIII, and helped guide the Cowboys to three Super Bowl titles. His 175 career touchdowns rank second in NFL history. In September 2005, Smith was added to the Cowboys Ring of Honor with former teammates Troy Aikman and Michael Irvin. Smith's post-career includes serving as an analyst for ESPN and the NFL Network and winning the third season of ABC's popular prime time reality show Dancing with the Stars. -

ANNUAL UCLA FOOTBALL AWARDS Henry R

2005 UCLA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE NON-PUBLISHED SUPPLEMENT UCLA CAREER LEADERS RUSHING PASSING Years TCB TYG YL NYG Avg Years Att Comp TD Yds Pct 1. Gaston Green 1984-87 708 3,884 153 3,731 5.27 1. Cade McNown 1995-98 1,250 694 68 10,708 .555 2. Freeman McNeil 1977-80 605 3,297 102 3,195 5.28 2. Tom Ramsey 1979-82 751 441 50 6,168 .587 3. DeShaun Foster 1998-01 722 3,454 260 3,194 4.42 3. Cory Paus 1999-02 816 439 42 6,877 .538 4. Karim Abdul-Jabbar 1992-95 608 3,341 159 3,182 5.23 4. Drew Olson 2002- 770 422 33 5,334 .548 5. Wendell Tyler 1973-76 526 3,240 59 3,181 6.04 5. Troy Aikman 1987-88 627 406 41 5,298 .648 6. Skip Hicks 1993-94, 96-97 638 3,373 233 3,140 4.92 6. Tommy Maddox 1990-91 670 391 33 5,363 .584 7. Theotis Brown 1976-78 526 2,954 40 2,914 5.54 7. Wayne Cook 1991-94 612 352 34 4,723 .575 8. Kevin Nelson 1980-83 574 2,687 104 2,583 4.50 8. Dennis Dummit 1969-70 552 289 29 4,356 .524 9. Kermit Johnson 1971-73 370 2,551 56 2,495 6.74 9. Gary Beban 1965-67 465 243 23 4,087 .522 10. Kevin Williams 1989-92 418 2,348 133 2,215 5.30 10. Matt Stevens 1983-86 431 231 16 2,931 .536 11. -

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

The Following Players Comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set

COLLEGE FOOTBALL GREAT TEAMS OF THE PAST 2 SET ROSTER The following players comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. 1971 NEBRASKA 1971 NEBRASKA 1972 USC 1972 USC OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Woody Cox End: John Adkins EB: Lynn Swann TA End: James Sims Johnny Rodgers (2) TA TB, OA Willie Harper Edesel Garrison Dale Mitchell Frosty Anderson Steve Manstedt John McKay Ed Powell Glen Garson TC John Hyland Dave Boulware (2) PA, KB, KOB Tackle: John Grant Tackle: Carl Johnson Tackle: Bill Janssen Chris Chaney Jeff Winans Daryl White Larry Jacobson Tackle: Steve Riley John Skiles Marvin Crenshaw John Dutton Pete Adams Glenn Byrd Al Austin LB: Jim Branch Cliff Culbreath LB: Richard Wood Guard: Keith Wortman Rich Glover Guard: Mike Ryan Monte Doris Dick Rupert Bob Terrio Allan Graf Charles Anthony Mike Beran Bruce Hauge Allan Gallaher Glen Henderson Bruce Weber Monte Johnson Booker Brown George Follett Center: Doug Dumler Pat Morell Don Morrison Ray Rodriguez John Kinsel John Peterson Mike McGirr Jim Stone ET: Jerry List CB: Jim Anderson TC Center: Dave Brown Tom Bohlinger Brent Longwell PC Joe Blahak Marty Patton CB: Charles Hinton TB. -

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Apr. 26, 2003 DALLAS—Big 12 Conference teams had 10 of the first 62 selections in the 35th annual NFL “common” draft (67th overall) Saturday and added a total of 13 for the opening day. The first-day tallies in the 2003 NFL draft brought the number Big 12 standouts taken from 1995-03 to 277. Over 90 Big 12 alumni signed free agent contracts after the 2000-02 drafts, and three of the first 13 standouts (six total in the first round) in the 2003 draft were Kansas State CB Terence Newman (fifth draftee), Oklahoma State DE Kevin Williams (ninth) Texas A&M DT Ty Warren (13th). Last year three Big 12 standouts were selected in the top eight choices (four of the initial 21), and the 2000 draft included three alumni from this conference in the first 20. Colorado, Nebraska and Florida State paced all schools nationally in the 1995-97 era with 21 NFL draft choices apiece. Eleven Big 12 schools also had at least one youngster chosen in the eight-round draft during 1998. Over the last six (1998-03) NFL postings, there were 73 Big 12 Conference selections among the Top 100. There were 217 Big 12 schools’ grid representatives on 2002 NFL opening day rosters from all 12 members after 297 standouts from league members in ’02 entered NFL training camps—both all-time highs for the league. Nebraska (35 alumni) was third among all Division I-A schools in 2002 opening day roster men in the highest professional football configuration while Texas A&M (30) was among the Top Six in total NFL alumni last autumn. -

Mental Health Professionals According to Prime-Time: an Exploratory Analysis

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 424 499 CG 028 776 AUTHOR Diefenbach, Donald L.; Burns, Naomi J.; Schwartz, Alan L. TITLE Mental Health Professionals According to Prime-Time: An Exploratory Analysis. PUB DATE 1998-08-00 NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Convention (106th, San Francisco, CA, August 14-18, 1998). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143)-- Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Television; *Mass Media Effects; Media Research; Mental Health Workers; Television Research IDENTIFIERS *Prime Time Television ABSTRACT The public receives a large percentage of its information about mental health issues from media sources. Research has shown that the portrayal of occupational roles is often distorted and unrealistic. Cultivation theory predicts that television's version of reality helps influence or "cultivate" viewers' beliefs about the world. This cultivation might influence a person's expectations or behavior during an encounter with these professionals, or even influence viewers' decisions to consult these professionals when in need of service. Research for this paper employed mixed methods to explore how mental health professionals are portrayed on television. Analysis of characters involved a random sample across all genres of programming. Trained coders (n=9) identified 10 out of 1,844 speaking characters as mental health professionals. Descriptive statistics are reported on the characters. A content analysis by type of programming-is presented and discussed. Exploratory analysis examining the portrayal of mental health professionals on prime-time television indicates that portrayals can not be classified by tone in a single category; however tone appears to be consistent within certain programming genres. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign !~he Quad s the :enter of :ampus ife 3 . H«H» H 1 i % UI 6 U= tiii L L,._ L-'IA-OHAMPAIGK The 1990 Illinois Football Media Guide • The University of Illinois . • A 100-year Tradition, continued ~> The University at a Glance 118 Chronology 4 President Stanley Ikenberrv • The Athletes . 4 Chancellor Morton Weir 122 Consensus All-American/ 5 UI Board of Trustees All-Big Ten 6 Academics 124 Football Captains/ " Life on Campus Most Valuable Players • The Division of 125 All-Stars Intercollegiate Athletics 127 Academic All-Americans/ 10 A Brief History Academic All-Big Ten 11 Football Facilities 128 Hall of Fame Winners 12 John Mackovic 129 Silver Football Award 10 Assistant Coaches 130 Fighting Illini in the 20 D.I.A. Staff Heisman Voting • 1990 Outlook... 131 Bruce Capel Award 28 Alpha/Numerical Outlook 132 Illini in the NFL 30 1990 Outlook • Statistical Highlights 34 1990 Fighting Illini 134 V early Statistical Leaders • 1990 Opponents at a Glance 136 Individual Records-Offense 64 Opponent Previews 143 Individual Records-Defense All-Time Record vs. Opponents 41 NCAA Records 75 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 78 UI Travel Plans/ 145 Freshman /Single-Play/ ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Opponent Directory Regular Season UNIVERSITY OF responsible for its charging this material is • A Look back at the 1989 Season Team Records The person on or before theidue date. 146 Ail-Time Marks renewal or return to the library Sll 1989 Illinois Stats for is $125.00, $300.00 14, Top Performances minimum fee for a lost item 82 1989 Big Ten Stats The 149 Television Appearances journals. -

How Andre Gurode Became Cowboys' Most Tenured Veteran | Todd Archer Columns | Spo

How Andre Gurode became Cowboys' most tenured veteran | Todd Archer Columns | Spo... Page 1 of 2 How Andre Gurode became Cowboys' most tenured veteran 10:49 AM CDT on Friday, May 21, 2010 IRVING – At times, Andre Gurode admits he will look around the Valley Ranch locker room and wonder where the time has gone. He can point across the room to where Emmitt Smith held court. He can look to his right and know that Terence Newman now occupies Darren Woodson’s old locker with a message about the Super Bowl tradition on its back wall. He can look straight ahead and see where Flozell Adams sat for years. Now Gurode is the old man in the room. Not in terms of age or years of NFL service – those go to backup quarterback Jon Kitna (37 and 14 respectively) – but in tenure with the Cowboys. Gurode is entering his eighth season with the Cowboys. “I wouldn’t say it felt like yesterday,” said Gurode, a second round pick in 2002 after Roy Williams and before Antonio Bryant, “but it felt like I just came here a few years ago. I couldn’t imagine going through the stuff I’ve been through and the years and just all of the things it took to get to this point. It’s like, ‘Wow, it’s really been a journey.’” Gurode was Adams’ teammate for eight years, who was once Michael Irvin’s teammate, who played with Everson Walls, who was a Cowboy with Harvey Martin, who played defensive line with Bob Lilly, the Cowboys’ first draft pick in 1961, who came a year after Eddie LeBaron was the quarterback for an 0-11-1 team in the franchise’s first year. -

Super Bowl 50

50 DAYS TO SUPER BOWL 50 A DAY-BY-DAY, SUPER BOWL-BY-SUPER BOWL LOOK AT THE IMPACT OF BLACK COLLEGE PLAYERS ON SUPER BOWLS I THRU 49 AS WE COUNT DOWN THE 50 DAYS TO SUPER BOWL 50 DAY 30 - Tuesday, January 19 SUPER Bowl XXX Dallas 27, Pittsburgh 17 January 28, 1996 - Sun Devil Stadium, Tempe, AR Eight (8) Black College Players Pittsburgh Steelers (5) Johnnie Barnes WR Hampton Randy Fuller DB Tennessee State Tracy Greene TE Grambling Greg Lloyd LB Fort Valley State Yancey Thigpen WR Winston-Salem State Dallas Cowboys (3) Greg Briggs DB Texas Southern Nate Newton OG Florida A&M Erik Williams OT Central State ICONIC PHOTO: Dallas defensive back and Super Bowl XXX MVP Larry Brown (#24) runs down to the PIttsburgh 18 with one of his two interceptions. Storyline: Pittsburgh quarterback Neil O’Donnell’s three interceptions, two by Dallas defensive back Larry Brown who was named MVP, doomed the Steelers in Super Bowl XXX. They held Emmit Smith to 49 yards on 18 carries but he scored on two short second-half touchdown runs (1, 4). Pittsburgh Greg Lloyd, OLB (Fort Valley State) Two solo tackles, five assists and one pass break-up in loss to Dal- las. - Teamed with linebacker LeVon Kirkland to bring down Dallas run- ning back Emmit Smith after 6-yard run to the left. - Teams with defensive back Carnell Lake to stop Michael Irvin after 12-yard pass from quarterback Troy Aikman. Next play, teams with linebacker Jerry Olsavsky to stop Smith after 4-yard run up the mid- dle. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

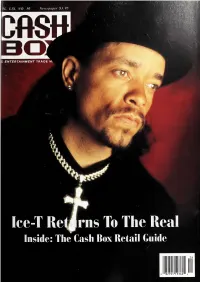

Ice-T Re^Rns to the Real Inside: the Cash Box Retail Guide

'f)L. LIX, NO. 30 Newspaper $3.95 ftSo E ENTERTAINMENT TRADE M. rj V;K Ice-T Re^rns To The Real Inside: The Cash Box Retail Guide 0 82791 19360 4 VOL. LIX, NO. 30 April 6, 1996 NUMBER ONES STAFF GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher POP SINGLE KEITH ALBERT THE ENTERTAINMENT TRADE MAGAZINE Exec. V.PJOeneral Manager Always Baby Be My M.R. MARTINEZ Mariah Carey Managing Editor (Columbia) EDITORIAL Los Angdes JOhM GOFF GIL ROBERTSON IV DAINA DARZIN URBAN SINGLE HECTOR RESENDEZ, Latin Edtor Cover Story Nashville Down Low ^AENDY NEWCOMER New York R. Kelly Ice-T Keeps It Real J.S GAER (Jive) CHART RESEARCH He’s established himself as a rapper to be reckoned with, and has encountered Los Angdes BRIAN PARMELLY his share of controversy along the way. But Ice-T doesn’t mind keepin’ it real, ZIV RAP SINGLE which is the key element in his new Rhyme Syndicate/ Priority release Ice VI: TONY RUIZ PETER FIRESTONE The Return Of The Real. The album is being launched into the consciousness of Woo-Hah! Got You... Retail Gude Research fans and foes with a wickedly vigorous marketing and media campaign that LAURI Busta Rhymes Nashville artist’s power. Angeles-based rapper talks with underscores the The Los Cash GAIL FRANCESCHl (Elektra) Box urban editor Gil Robertson IV about the record, his view of the industry MARKETINO/ADVERTISINO today and his varied creative ventures. Los A^gdes FRANK HIGGINBOTHAM —see page 5 JOI-TJ RHYS COUNTRY SINGLE BOB CASSELL Nashville To Be Loved By You The Cash Box Retail Guide Inside! TED RANDALL V\^nonna New York NOEL ALBERT (Curb) CIRCULATION NINATREGUB, Managa- Check Out Cash Box on The Internet at JANET YU PRODUCTION POP ALBUM HTTP: //CASHBOX.COM.