The Migrant 20:2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Gilbert White: a Biography of the Author of the Natural History of Selborne

Review: Gilbert White: A Biography of the Author of The Natural History of Selborne. By Richard Mabey Reviewed by Elery Hamilton-Smith Charles Sturt University, Australia Mabey, Richard. Gilbert White: A Biography of the Author of The Natural History of Selborne. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007. 239pp. ISBN 978-0-8139-2649-0. US$16.50. Permit me to commence with a little personal reminiscence. I grew up in a rural area, and at 8 years of age (a year prior to attending school as it entailed a three-mile walk), I was given a copy of White’s Natural History. It confirmed my nascent interest in and feeling for the natural environment, and cemented it firmly into a permanent home within my mind. White was one of the first to write about natural history with a “sense of intimacy, or wonder or respect – in short, of human engagement with nature.”Many of those who read and re-read this wondrous book knew that White was curate in a small English village and that both Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington had encouraged White to systematically record his observations and descriptive studies of the village. The outcome was the book that so many of us know and love – one of the most frequently published English language books of all time. It appears as a series of letters to each of White’s great mentors. Regrettably White wrote very little, even in his extensive journals and diaries, of his personal life or feelings. Mabey has made an exhaustive search of the available data, and has built a delightful re-construction of the author as a person. -

285 East US Highway 20, Furnessville Researche

9/07.2 Edwin Way Teale May 30, 2008 9/07.2 Edwin Way Teale Porter County Site: 285 East U.S. Highway 20, Furnessville Researcher: Jill Weiss RESEARCH SUMMARY American naturalists have been cited for combining philosophy and writing in ways that have affected how concerned citizens value and care for their environment.1 Edwin Way Teale has been called one of the twentieth century’s most influential naturalists because of his ability to combine the artistic, philosophical, and scientific in his writing.2 According to the extensive Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists, “Through his popular books [Teale] convinced Americans they had a personal stake in the preservation of ecological zones [and] convinced them to support national parks and conservation movements.”3 Teale credited his renowned career to his rich childhood spent in the Indiana Dunes, where he developed a love for nature, an eye for photography, and an accessible writing style. 4 He immortalized his boyhood adventures in Dune Boy and later works,5 including Wandering through Winter, for which he became the first naturalist to win a Pulitzer Prize.6 Teale is included in the “heyday of dunes art and literature begun and perpetuated” by a group of artists of the “Chicago Renaissance” movement.7 Naturalists, conservationists, writers, and reviewers have ranked him among the renowned American naturalists who preceded him, including John Muir, John Burroughs, and Henry David Thoreau.8 Born Edwin Alfred Teale9 on June 2, 1899 in Joliet, Illinois,10 -

Migration of Swallows

Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (I978) vol 6o HUNTERIANA John Hunter, Gilbert White, and the migration of swallows I F Lyle, ALA Library of the Royal College of Surgeons of England Introduction fied than himself, although he frequently sug- gested points that would be worthy of investi- This year is not only the 25oth anniversary of gation by others. Hunter, by comparison, was John Hunter's birth, but it is also I90 years the complete professional and his work as a since the publication of Gilbert White's Nat- comparative anatomist was complemented by ural History and Antiquities of Selborne in White's fieldwork. The only occasion on which December I788. White and Hunter were con- they are known to have co-operated was in temporaries, White being the older man by I768, when White, through an intermediary, eight years, and both died in I 793. Despite asked Hunter to undertake the dissection of a their widely differing backgrounds and person- buck's head to discover the true function of the alities they had two very particular things in suborbital glands in deer3. Nevertheless, common. One was their interest in natural there were several subjects in natural history history, which both had entertained from child- that interested both of them, and one of these hood and in which they were both self-taught. was the age-old question: What happens to In later life both men referred to this. Hunter swallows in winter? wrote: 'When I was a boy, I wanted to know all about the Background and history clouds and the grasses, and why the leaves changed colour in the autumn; I watched the ants, bees, One of the most contentious issues of eight- birds, tadpoles, and caddisworms; I pestered people eenth-century natural history was with questions about what nobody knew or cared the disap- anything about". -

Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists 11 March – 28 June 2020

Press Release 2020 Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists 11 March – 28 June 2020 Pallant House Gallery is delighted to announce an exhibition of artworks depicting Britain’s animals, birds and natural life to mark the 300th anniversary of the birth of ‘Britain’s first ecologist’ Gilbert White of Selborne. Featuring works by artists including Thomas Bewick, Eric Ravilious, Clare Leighton, Gertrude Hermes and John Piper, it highlights the natural life under threat as we face a climate emergency. The parson-naturalist the Rev. Gilbert White Eric Ravilious, The Tortoise in the Kitchen Garden (1720 – 1793) recorded his observations about from ‘The Writings of Gilbert White of Selborne’, ed., the natural life in the Hampshire village of H.J. Massingham (London, The Nonsuch Press, Selborne in a series of letters which formed his 1938), Private Collection famous book The Natural History and Antiquities editions, it is believed to be the fourth most- of Selborne. White has been described as ‘the published book in English, after the Bible, the first ecologist’ as he believed in studying works of Shakespeare and John Bunyan’s The creatures in the wild rather than dead Pilgrim’s Progress. Poets such as WH Auden, specimens: he made the first field observations John Clare, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge have to prove the existence of three kinds of leaf- admired his poetic use of language, whilst warblers: the chiff-chaff, the willow-warbler and Virginia Woolf declared how, ‘By some the wood-warbler – and he also discovered and apparently unconscious device of the author has named the harvest-mouse and the noctule bat. -

Biblioqraphy & Natural History

BIBLIOQRAPHY & NATURAL HISTORY Essays presented at a Conference convened in June 1964 by Thomas R. Buckman Lawrence, Kansas 1966 University of Kansas Libraries University of Kansas Publications Library Series, 27 Copyright 1966 by the University of Kansas Libraries Library of Congress Catalog Card number: 66-64215 Printed in Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A., by the University of Kansas Printing Service. Introduction The purpose of this group of essays and formal papers is to focus attention on some aspects of bibliography in the service of natural history, and possibly to stimulate further studies which may be of mutual usefulness to biologists and historians of science, and also to librarians and museum curators. Bibli• ography is interpreted rather broadly to include botanical illustration. Further, the intent and style of the contributions reflects the occasion—a meeting of bookmen, scientists and scholars assembled not only to discuss specific examples of the uses of books and manuscripts in the natural sciences, but also to consider some other related matters in a spirit of wit and congeniality. Thus we hope in this volume, as in the conference itself, both to inform and to please. When Edwin Wolf, 2nd, Librarian of the Library Company of Phila• delphia, and then Chairman of the Rare Books Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries, asked me to plan the Section's program for its session in Lawrence, June 25-27, 1964, we agreed immediately on a theme. With few exceptions, we noted, the bibliography of natural history has received little attention in this country, and yet it is indispensable to many biologists and to historians of the natural sciences. -

The Illustrated Natural History of Selborne Free

FREE THE ILLUSTRATED NATURAL HISTORY OF SELBORNE PDF Gilbert White,June E. Chatfield | 256 pages | 13 Apr 2004 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500284780 | English | London, United Kingdom Read Download The Illustrated Natural History Of Selborne PDF – PDF Download More than two centuries have passed since Gilbert While was laid to rest in his unassuming grave in Selborne churchyard but published instill makes delightful reading today. His regular correspondence, beginning inwith two distinguished naturalists, Thomas Pennant and the Honourable Daines Barrington, forms the basis The Illustrated Natural History of Selborne The Natural History of Selborne. Originally published as part of: The natural history and antiquities of Selborne, in the county of Southampton. London: Printed by T. Bensley for B. White and Son, With new introduction, additional illustrations, and some corrections and notes by the editor. With notes, by T. With extensive additions, by Captain Thomas Brown Illustrated with engravings. The Illustrated Natural History Published by Good Press. Good Press publishes a wide range of titles that encompasses every genre. Each Good Press edition has been meticulously edited and formatted to boost readability for all e-readers and devices. Our goal is to produce eBooks that are user-friendly and accessible to everyone in a high-quality digital format. According to Bruce Ashford and Craig Bartholomew, one of the best sources for regaining a robust, biblical doctrine of creation is the recovery of Dutch neo-Calvinism. Tracing historical treatments and exploring theological themes, Ashford and Bartholomew develop the Kuyperian tradition's rich resources on creation for systematic theology and the life of the church today. -

Cultural Responses to the Migration of the Barn Swallow in Europe Ashleigh Green University of Melbourne

Cultural responses to the migration of the barn swallow in Europe Ashleigh Green University of Melbourne Abstract: This paper investigates the place of barn swallows in European folklore and science from the Bronze Age to the nineteenth century. It takes the swallow’s natural migratory patterns as a starting point, and investigates how different cultural groups across this period have responded to the bird’s departure in autumn and its subsequent return every spring. While my analysis is focused on classical European texts, including scientific and theological writings, I have also considered the swallow’s representation in art. The aim of this article is to build alongue durée account of how beliefs about the swallow have evolved over time, even as the bird’s migratory patterns have remained the same. As I argue, the influence of classical texts on medieval and Renaissance thought in Europe allows us to consider a temporal progression (and sometimes regression) in the way barn swallow migration was explained and understood. The barn swallow The barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) has two defining characteristics that have shaped how people living in Europe have responded to its presence over the centuries. The first relates to its movement across continents. The swallow migrates to Africa every autumn and returns to Asia in spring for breeding. Second, it is a bird that is often found in urban environments, typically nesting in or on buildings to rear its young.1 These two characteristics have meant that the barn swallow has been a feature of European life for centuries and has prompted a myriad of responses in science and folklore—particularly in Greek mythology. -

Newsletter and Proceedings of the LINNEAN SOCIETY of LONDON Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF

THE LINNEAN Newsletter and Proceedings of THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF VOLUME 19 • NUMBER 2 • APRIL 2003 THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF Tel. (+44) (0)20 7434 4479; Fax: (+44) (0)20 7287 9364 e-mail: [email protected]; internet: www.linnean.org President Secretaries Council Sir David Smith FRS FRSE BOTANICAL The Officers and Dr J R Edmondson Dr R M Bateman President-Elect Prof. S Blackmore Professor G McG Reid ZOOLOGICAL Dr H E Gee Dr V R Southgate Mr M D Griffiths Vice Presidents Dr P Kenrick Professor D F Cutler EDITORIAL Dr S D Knapp Dr D T J Littlewood Professor D F Cutler Mr T E Langford Dr V R Southgate Dr A M Lister Dr J M Edmonds Librarian & Archivist Dr D T J Littlewood Miss Gina Douglas Dr E C Nelson Treasurer Mr L A Patrick Professor G Ll Lucas OBE Assistant Librarian Dr A D Rogers Ms Cathy Broad Dr E Sheffield Executive Secretary Dr D A Simpson Dr John Marsden Catalogue Coordinator Ms Lynn Crothall (2002) Assistant Secretary Ms Janet Ashdown (2002) Membership & House Manager Mr David Pescod Finance Mr Priya Nithianandan Information Technology Mr D. Thomas THE LINNEAN Newsletter and Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London Edited by B. G. Gardiner Editorial ................................................................................................................ 4 Society News ............................................................................................................... 5 Library ............................................................................................................... -

PDF Download Gilbert White

GILBERT WHITE: A BIOGRAPHY OF THE AUTHOR OF THE NATURAL HISTORY OF SELBORNE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Mabey | 256 pages | 08 Jun 2006 | Profile Books Ltd | 9781861978073 | English | London, United Kingdom Gilbert White: A Biography of the Author of The Natural History of Selborne PDF Book Which is really basic, but these folks are the ones who got the ball rolling. So I finally decided to see what all the fuss was about. There is one known hawfinch specimen in the collections of the Gilbert White Museum which is likely one of White's. The manuscript for the book stayed in the White family until , when it was auctioned at Sotheby's. These take place over a number of years in the 18th century within his immediate locality, the village of Selborne and its environs. Selborne is the parish where Gilbert White lived serving as parson. Open Preview See a Problem? White's History of Selborne has seldom been published Signed by the author. Let us know if you have suggestions to improve this article requires login. White's influence on artists is celebrated in the exhibition 'Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists' taking place in spring at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester to mark the th anniversary of his birth, and including artworks by Thomas Bewick , Eric Ravilious and John Piper , amongst others. The writing itself and the thoughtfulness that it stimulates has inspired admiration in uncounted numbers of readers throughout the centuries. View all 4 comments. Later that year he publishes a paper on the behaviour of other martin species. -

Natural History a Selection 1St Edition Kindle

NATURAL HISTORY A SELECTION 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pliny | 9780140444131 | | | | | Natural History A Selection 1st edition PDF Book An XML version of this text is available for download, with the additional restriction that you offer Perseus any modifications you make. He describes gold mining in detail, [67] with large-scale use of water to scour alluvial gold deposits. Pliny the Elder. Although recording natural phenomena - he tied watching the destruction of Pompeii from a ship in its harbor - he also recorded the weird beliefs of the day, such as the weasel being the most destructive of all creatures, so horrific even alligators fear it. Williams rated it really liked it. Pliny's Natural History was written alongside other substantial works which have since been lost. Download Hi Res. Completed items. Book II continues with natural meteorological events lower in the sky, including the winds, weather, whirlwinds, lightning, and rainbows. He was also a proud Roman citizen, engaged in the imperial project of sustaining Rome's geopolitical and cultural dominance. Mehr als die anderen Schriftsteller seiner Epoche widmet sich Plinius d. No jacket. About this Item: Swan Sonnenschein, London, Rather than review I want to make clear a concern of mine with this particular edition. His two favourite themes are how much better things were in the "good old days" BC was, as far as I can tell, the peak of civilization in Pliny's opinion and how greed and lust for material possessions has ruined the world here I agree with him. Download as PDF Printable version. Free postage. -

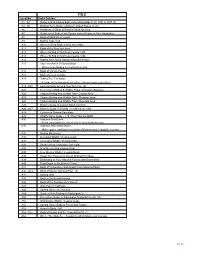

Location Field Guides

TITLE Location Field Guides A1 - A3 Guide to Bird Finding East of the Mississippi, A (1) 1951 & 1977 (2) A4 - A5 Birdwatcher's Guide to Eastern United States, A (2) A6 Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America A7 Guide to the Birds of the Squam Lakes Region of New Hampshire A8 Birds of Martha's Vineyard A9 Birding Cape Cod A10 Where to Find Birds in New York State A11 Birds of the New York Area A12 Where To Bird In Dutchess County 1977 A13 Where To Bird In Dutchess County 1990 A14 Birding New York's Hudson-Mohawk Region A15 City Cemeteries To Boreal Bogs - Where to go Birding in Central New York A16 Birds of Clinton County A17 Birds of Essex County A18 Taking Time For Nature - A Guide to 25 Natural Areas in the Eastern Finger Lakes Area A19 - A20 Enjoying Birds Around New York City (2) A21 New Jersey Birding & Wildlife Trails - Delaware Bayshore A22 Virginia Birding and Wildlife Trail - Coastal Area A23 Virginia Birding and Wildlife Trail - Piedmont Area A24 Virginia Birding and Wildlife Trail - Mountain Area A25 Birder's Guide to Coastal North Carolina A26 - A27 Birder's Guide To Florida (1) 1981 & (1) 1984 A28 Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary A29 Wildlife Drive Guide - J. N. "Ding" Darling NWR A30 Audubon Bird Guide - Small Land Birds of Eastern and Central North America A31 Audubon Water Bird Guide - Water, game, and large land birds of Eastern and Central N. America A32 Birding Minnesota A33 Nebraska Wildlife Viewing Guide A34 Coloradoa Wildlife Viewing Guide A35 Southeastern Coloradoa Trail Guide A36 New Mexico Bird Finding Guide A37 New