A Three-Stage Iterative Procedure for Space-Time Modeling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Mechanics

Classical Mechanics Hyoungsoon Choi Spring, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction4 1.1 Kinematics and Kinetics . .5 1.2 Kinematics: Watching Wallace and Gromit ............6 1.3 Inertia and Inertial Frame . .8 2 Newton's Laws of Motion 10 2.1 The First Law: The Law of Inertia . 10 2.2 The Second Law: The Equation of Motion . 11 2.3 The Third Law: The Law of Action and Reaction . 12 3 Laws of Conservation 14 3.1 Conservation of Momentum . 14 3.2 Conservation of Angular Momentum . 15 3.3 Conservation of Energy . 17 3.3.1 Kinetic energy . 17 3.3.2 Potential energy . 18 3.3.3 Mechanical energy conservation . 19 4 Solving Equation of Motions 20 4.1 Force-Free Motion . 21 4.2 Constant Force Motion . 22 4.2.1 Constant force motion in one dimension . 22 4.2.2 Constant force motion in two dimensions . 23 4.3 Varying Force Motion . 25 4.3.1 Drag force . 25 4.3.2 Harmonic oscillator . 29 5 Lagrangian Mechanics 30 5.1 Configuration Space . 30 5.2 Lagrangian Equations of Motion . 32 5.3 Generalized Coordinates . 34 5.4 Lagrangian Mechanics . 36 5.5 D'Alembert's Principle . 37 5.6 Conjugate Variables . 39 1 CONTENTS 2 6 Hamiltonian Mechanics 40 6.1 Legendre Transformation: From Lagrangian to Hamiltonian . 40 6.2 Hamilton's Equations . 41 6.3 Configuration Space and Phase Space . 43 6.4 Hamiltonian and Energy . 45 7 Central Force Motion 47 7.1 Conservation Laws in Central Force Field . 47 7.2 The Path Equation . -

Victorian Popular Science and Deep Time in “The Golden Key”

“Down the Winding Stair”: Victorian Popular Science and Deep Time in “The Golden Key” Geoffrey Reiter t is sometimes tempting to call George MacDonald’s fantasies “timeless”I and leave it at that. Such is certainly the case with MacDonald’s mystical fairy tale “The Golden Key.” Much of the criticism pertaining to this work has focused on its more “timeless” elements, such as its intrinsic literary quality or its philosophical and theological underpinnings. And these elements are not only important, they truly are the most fundamental elements needed for a full understanding of “The Golden Key.” But it is also important to remember that MacDonald did not write in a vacuum, that he was in fact interested in and engaged with many of the pressing issues of his day. At heart always a preacher, MacDonald could not help but interact with these issues, not only in his more openly didactic realistic novels, but even in his “timeless” fantasies. In the Victorian period, an era of discovery and exploration, the natural sciences were beginning to come into their own as distinct and valuable sources of knowledge. John Pridmore, examining MacDonald’s view of nature, suggests that MacDonald saw it as serving a function parallel to the fairy tale or fantastic story; it may be interpreted from the perspective of Christian theism, though such an interpretation is not necessary (7). Björn Sundmark similarly argues that in his works “MacDonald does not contradict science, nor does he press a theistic interpretation onto his readers” (13). David L. Neuhouser has concluded more assertively that while MacDonald was certainly no advocate of scientific pursuits for their own sake, he believed science could be of interest when examined under the aegis of a loving God (10). -

Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens

Downloaded from Microscopy Pioneers https://www.cambridge.org/core Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens Eric Clark From the website Molecular Expressions created by the late Michael Davidson and now maintained by Eric Clark, National Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 . IP address: [email protected] 170.106.33.22 Christiaan Huygens reliability and accuracy. The first watch using this principle (1629–1695) was finished in 1675, whereupon it was promptly presented , on Christiaan Huygens was a to his sponsor, King Louis XIV. 29 Sep 2021 at 16:11:10 brilliant Dutch mathematician, In 1681, Huygens returned to Holland where he began physicist, and astronomer who lived to construct optical lenses with extremely large focal lengths, during the seventeenth century, a which were eventually presented to the Royal Society of period sometimes referred to as the London, where they remain today. Continuing along this line Scientific Revolution. Huygens, a of work, Huygens perfected his skills in lens grinding and highly gifted theoretical and experi- subsequently invented the achromatic eyepiece that bears his , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at mental scientist, is best known name and is still in widespread use today. for his work on the theories of Huygens left Holland in 1689, and ventured to London centrifugal force, the wave theory of where he became acquainted with Sir Isaac Newton and began light, and the pendulum clock. to study Newton’s theories on classical physics. Although it At an early age, Huygens began seems Huygens was duly impressed with Newton’s work, he work in advanced mathematics was still very skeptical about any theory that did not explain by attempting to disprove several theories established by gravitation by mechanical means. -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

A Guide to Space Law Terms: Spi, Gwu, & Swf

A GUIDE TO SPACE LAW TERMS: SPI, GWU, & SWF A Guide to Space Law Terms Space Policy Institute (SPI), George Washington University and Secure World Foundation (SWF) Editor: Professor Henry R. Hertzfeld, Esq. Research: Liana X. Yung, Esq. Daniel V. Osborne, Esq. December 2012 Page i I. INTRODUCTION This document is a step to developing an accurate and usable guide to space law words, terms, and phrases. The project developed from misunderstandings and difficulties that graduate students in our classes encountered listening to lectures and reading technical articles on topics related to space law. The difficulties are compounded when students are not native English speakers. Because there is no standard definition for many of the terms and because some terms are used in many different ways, we have created seven categories of definitions. They are: I. A simple definition written in easy to understand English II. Definitions found in treaties, statutes, and formal regulations III. Definitions from legal dictionaries IV. Definitions from standard English dictionaries V. Definitions found in government publications (mostly technical glossaries and dictionaries) VI. Definitions found in journal articles, books, and other unofficial sources VII. Definitions that may have different interpretations in languages other than English The source of each definition that is used is provided so that the reader can understand the context in which it is used. The Simple Definitions are meant to capture the essence of how the term is used in space law. Where possible we have used a definition from one of our sources for this purpose. When we found no concise definition, we have drafted the definition based on the more complex definitions from other sources. -

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geochronology Database for Central Colorado By T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt, 2009, Geochronology database for central Colorado: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 489, 13 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

Career Stage, Time Spent on the Road, and Truckload Driver Attitudes

CAREER STAGE, TIME SPENT ON THE ROAD, AND TRUCKLOAD DRIVER ATTITUDES James C. McElroy Julene M. Rodriguez Gene C. Griffin Paula C. Morrow Michael G. Wilson UGPTI Staff Paper No. 113 May 1993 Career Stage, Time Spent on the Road, And Truckload Driver Attitudes1 James C. McElroy, Department of Management Iowa State University Julene M. Rodriguez and Gene C. Griffin Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute North Dakota State University Paula C. Morrow Industrial Relations Center Iowa State University Michael G. Wilson Iowa State University Address correspondence to: James C. McElroy, Chair Departments of Management, Marketing, and Transportation & Logistics Iowa State University 300 Carver Hall Ames, Iowa 50011 1The authors would like to thank their respective institutions for support, Drs. Ben Allen, Michael Crum, Richard Poist, and David Shrock for their comments and suggestions and Brenda Lantz for her assistance with data analysis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CAREER STAGE, TIME SPENT ON THE ROAD, AND TRUCKLOAD DRIVER ATTITUDES ......................................... 1 Determinants of Work-Related Attitudes ......................................... 2 Propositions ................................................................ 3 Method ................................................................... 3 Sample ................................................................ 3 Independent Variables ...................................................... 4 Dependent Variables ....................................................... 4 Research -

It's About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for U.S

I t’s About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for U.S. Geochronology About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for t’s It’s About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for U.S. Geochronology 222508_Cover_r1.indd 1 2/23/15 6:11 PM A view of the Bowen River valley, demonstrating the dramatic scenery and glacial imprint found in Fiordland National Park, New Zealand. Recent innovations in geochronology have quantified how such landscapes developed through time; Shuster et al., 2011. Photo taken Cover photo: The Grand Canyon, recording nearly two billion years of Earth history (photo courtesy of Dr. Scott Chandler) from near the summit of Sheerdown Peak (looking north); by J. Sanders. 222508_Cover.indd 2 2/21/15 8:41 AM DEEP TIME is what separates geology from all other sciences. This report presents recommendations for improving how we measure time (geochronometry) and use it to understand a broad range of Earth processes (geochronology). 222508_Text.indd 3 2/21/15 8:42 AM FRONT MATTER Written by: T. M. Harrison, S. L. Baldwin, M. Caffee, G. E. Gehrels, B. Schoene, D. L. Shuster, and B. S. Singer Reviews and other commentary provided by: S. A. Bowring, P. Copeland, R. L. Edwards, K. A. Farley, and K. V. Hodges This report is drawn from the presentations and discussions held at a workshop prior to the V.M. Goldschmidt in Sacramento, California (June 7, 2014), a discussion at the 14th International Thermochronology Conference in Chamonix, France (September 9, 2014), and a Town Hall meeting at the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting in Vancouver, Canada (October 21, 2014) This report was provided to representatives of the National Science Foundation, the U.S. -

Energy Harvesters for Space Applications 1

Energy harvesters for space applications 1 Energy harvesters for space R. Graczyk limited, especially that they are likely to operate in charge Abstract—Energy harvesting is the fundamental activity in (energy build-up in span of minutes or tens of minutes) and almost all forms of space exploration known to humans. So far, act (perform the measurement and processing quickly and in most cases, it is not feasible to bring, along with probe, effectively). spacecraft or rover suitable supply of fuel to cover all mission’s State-of-the-art research facilitated by growing industrial energy needs. Some concepts of mining or other form of interest in energy harvesting as well as innovative products manufacturing of fuel on exploration site have been made, but they still base either on some facility that needs one mean of introduced into market recently show that described energy to generate fuel, perhaps of better quality, or needs some techniques are viable source of energy for sensors, sensor initial energy to be harvested to start a self sustaining cycle. networks and personal devices. Research and development Following paper summarizes key factors that determine satellite activities include technological advances for automotive energy needs, and explains some either most widespread or most industry (tire pressure monitors, using piezoelectric effect ), interesting examples of energy harvesting devices, present in Earth orbit as well as exploring Solar System and, very recently, aerospace industry (fuselage sensor network in aircraft, using beyond. Some of presented energy harvester are suitable for thermoelectric effect), manufacturing automation industry very large (in terms of size and functionality) probes, other fit (various sensors networks, using thermoelectric, piezoelectric, and scale easily on satellites ranging from dozens of tons to few electrostatic, photovoltaic effects), personal devices (wrist grams. -

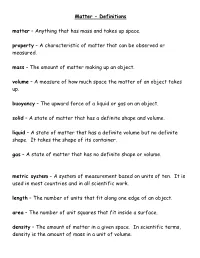

Definitions Matter – Anything That Has Mass and Takes up Space. Property – a Characteristic of Matter That Can Be Observed Or Measured

Matter – Definitions matter – Anything that has mass and takes up space. property – A characteristic of matter that can be observed or measured. mass – The amount of matter making up an object. volume – A measure of how much space the matter of an object takes up. buoyancy – The upward force of a liquid or gas on an object. solid – A state of matter that has a definite shape and volume. liquid – A state of matter that has a definite volume but no definite shape. It takes the shape of its container. gas – A state of matter that has no definite shape or volume. metric system – A system of measurement based on units of ten. It is used in most countries and in all scientific work. length – The number of units that fit along one edge of an object. area – The number of unit squares that fit inside a surface. density – The amount of matter in a given space. In scientific terms, density is the amount of mass in a unit of volume. weight – The measure of the pull of gravity between an object and Earth. gravity – A force of attraction, or pull, between objects. physical change – A change that begins and ends with the same type of matter. change of state – A physical change of matter from one state – solid, liquid, or gas – to another state because of a change in the energy of the matter. evaporation – The process of a liquid changing to a gas. rust – A solid brown compound formed when iron combines chemically with oxygen. chemical change – A change that produces new matter with different properties from the original matter. -

End Times Timeline CCC August 30, 2020 Visuals

End Times Timeline CCC August 30, 2020 Visuals – Across the stage signage. Four signs representing each age. Three cutouts – One of Rapture, one of Second Coming, one of Zombie Introduction – Quick show of hands. How many people have ever found end times stuff to be Confusing? If your neighbor just raised his/her hand, say to them “I knew you were confused.” How would you like to have a quick handle on what is going to happen when Jesus comes back again? Today, I am going to try to make that happen in under 40 minutes. So lets pray. Seriously… Pray OK, so the end times are so crazy partly because of terminology. Partly because of theological positions. Partly because the Bible is crystal clear on some things – like Jesus is coming back. Unclear on other things – like what is the order of events. And downright intentionally obtuse about other things – like when the rapture will take place. So I am going to run after this with a really clear statement up front. “I might be wrong.” I know… a shocking thing for a pastor to admit. Now raise your eyebrows and turn to the person next to you and say – he might be wrong. (really, I wont do that all message). I have studied this for 30 years now and changed my mind a few times. I may change it again in five years. I may have never been right on some aspects – so I’ll do my best to share multiple views and my personal opinion… but just so you know that I know that this is complex stuff that will come down in the future – and I am approaching it all with humility – and I’ll let you know if I change my mind. -

A Chronology for Late Prehistoric Madagascar

Journal of Human Evolution 47 (2004) 25e63 www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar a,) a,b c David A. Burney , Lida Pigott Burney , Laurie R. Godfrey , William L. Jungersd, Steven M. Goodmane, Henry T. Wrightf, A.J. Timothy Jullg aDepartment of Biological Sciences, Fordham University, Bronx NY 10458, USA bLouis Calder Center Biological Field Station, Fordham University, P.O. Box 887, Armonk NY 10504, USA cDepartment of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Amherst MA 01003, USA dDepartment of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook NY 11794, USA eField Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. Roosevelt Rd., Chicago, IL 60605, USA fMuseum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA gNSF Arizona AMS Facility, University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85721, USA Received 12 December 2003; accepted 24 May 2004 Abstract A database has been assembled with 278 age determinations for Madagascar. Materials 14C dated include pretreated sediments and plant macrofossils from cores and excavations throughout the island, and bones, teeth, or eggshells of most of the extinct megafaunal taxa, including the giant lemurs, hippopotami, and ratites. Additional measurements come from uranium-series dates on speleothems and thermoluminescence dating of pottery. Changes documented include late Pleistocene climatic events and, in the late Holocene, the apparently human- caused transformation of the environment. Multiple lines of evidence point to the earliest human presence at ca. 2300 14C yr BP (350 cal yr BC). A decline in megafauna, inferred from a drastic decrease in spores of the coprophilous fungus Sporormiella spp. in sediments at 1720 G 40 14C yr BP (230e410 cal yr AD), is followed by large increases in charcoal particles in sediment cores, beginning in the SW part of the island, and spreading to other coasts and the interior over the next millennium.