78 Common Acute Pediatric Illnesses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health History

Health History Patient Name ___________________________________________ Date of Birth _______________ Reason for visit ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Past Medical History Have you ever had the following? (Mark all that apply) ☐ Alcoholism ☐ Cancer ☐ Endocarditis ☐ MRSA/VRE ☐ Allergies ☐ Cardiac Arrest ☐ Gallbladder disease ☐ Myocardial infarction ☐ Anemia ☐ Cardiac dysrhythmias ☐ GERD ☐ Osteoarthritis ☐ Angina ☐ Cardiac valvular disease ☐ Hemoglobinopathy ☐ Osteoporosis ☐ Anxiety ☐ Cerebrovascular accident ☐ Hepatitis C ☐ Peptic ulcer disease ☐ Arthritis ☐ COPD ☐ HIV/AIDS ☐ Psychosis ☐ Asthma ☐ Coronary artery disease ☐ Hyperlipidemia ☐ Pulmonary fibrosis ☐ Atrial fibrillation ☐ Crohn’s disease ☐ Hypertension ☐ Radiation ☐ Benign prostatic hypertrophy ☐ Dementia ☐ Inflammatory bowel disease ☐ Renal disease ☐ Bleeding disorder ☐ Depression ☐ Liver disease ☐ Seizure disorder ☐ Blood clots ☐ Diabetes ☐ Malignant hyperthermia ☐ Sleep apnea ☐ Blood transfusion ☐ DVT ☐ Migraine headaches ☐ Thyroid disease Previous Hospitalizations/Surgeries/Serious Illnesses Have you ever had the following? (Mark all that apply and specify dates) Date Date Date Date ☐ AICD Insertion ☐ Cyst/lipoma removal ☐ Pacemaker ☐ Mastectomy ☐ Angioplasty ☐ ESWL ☐ Pilonidal cyst removal ☐ Myomectomy ☐ Angio w/ stent ☐ Gender reassignment ☐ Small bowel resection ☐ Penile implant ☐ Appendectomy ☐ Hemorrhoidectomy ☐ Thyroidectomy ☐ Prostate biopsy ☐ Arthroscopy knee ☐ Hernia surgery ☐ TIF ☐ TAH/BSO ☐ Bariatric surgery -

Identifying COPD by Crackle Characteristics

BMJ Open Resp Res: first published as 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000852 on 5 March 2021. Downloaded from Respiratory epidemiology Inspiratory crackles—early and late— revisited: identifying COPD by crackle characteristics Hasse Melbye ,1 Juan Carlos Aviles Solis,1 Cristina Jácome,2 Hans Pasterkamp3 To cite: Melbye H, Aviles ABSTRACT Key messages Solis JC, Jácome C, et al. Background The significance of pulmonary crackles, Inspiratory crackles— by their timing during inspiration, was described by Nath early and late—revisited: and Capel in 1974, with early crackles associated with What is the key question? identifying COPD by bronchial obstruction and late crackles with restrictive ► In the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary crackle characteristics. defects. Crackles are also described as ‘fine’ or disease (COPD), is it more useful to focus on the tim- BMJ Open Resp Res ‘coarse’. We aimed to evaluate the usefulness of crackle ing of crackles than on the crackle type? 2021;8:e000852. doi:10.1136/ bmjresp-2020-000852 characteristics in the diagnosis of chronic obstructive What is the bottom line? pulmonary disease (COPD). ► Pulmonary crackles are divided into two types, ‘fine’ Methods In a population-based study, lung sounds Received 2 December 2020 and ‘coarse’ and coarse inspiratory crackles are re- Revised 2 February 2021 were recorded at six auscultation sites and classified in garded to be typical of COPD. In bronchial obstruc- Accepted 5 February 2021 participants aged 40 years or older. Inspiratory crackles tion crackles tend to appear early in inspiration, and were classified as ‘early’ or ‘late and into the types’ this characteristic of the crackle might be easier for ‘coarse’ and ‘fine’ by two observers. -

Download Article

...& more SELF-TEST Respiratory system challenge Test your knowledge with this quick quiz. 1. Gas exchange takes place in the 8. Which continuous breath sounds are 14. Wheezes most commonly suggest a. pharynx. c. alveoli. relatively high pitched with a hissing a. secretions in large airways. b. larynx. d. trachea. or shrill quality? b. abnormal lung tissue. a. coarse crackles c. wheezes c. airless lung areas. 2. The area between the lungs is b. rhonchi d. fine crackles d. narrowed airways. known as the a. thoracic cage. c. pleura. 9. Normal breath sounds heard over 15. Which of the following indicates a b. mediastinum. d. hilum. most of both lungs are described as partial obstruction of the larynx or being trachea and demands immediate 3. Involuntary breathing is controlled by a. loud. c. very loud. attention? a. the pulmonary arterioles. b. intermediate. d. soft. a. rhonchi c. pleural rub b. the bronchioles. b. stridor d. mediastinal crunch c. the alveolar capillary network. 10. Bronchial breath sounds are d. neurons located in the medulla and normally heard 16. Which of the following would you pons. a. over most of both lungs. expect to find over the involved area b. between the scapulae. in a patient with lobar pneumonia? 4. The sternal angle is also known as c. over the manubrium. a. vesicular breath sounds the d. over the trachea in the neck. b. egophony a. suprasternal notch. c. scapula. c. decreased tactile fremitus b. xiphoid process. d. angle of Louis. 11. Which is correct about vesicular d. muffled and indistinct transmitted voice breath sounds? sounds 5. -

Age-Related Pulmonary Crackles (Rales) in Asymptomatic Cardiovascular Patients

Age-Related Pulmonary Crackles (Rales) in Asymptomatic Cardiovascular Patients 1 Hajime Kataoka, MD ABSTRACT 2 Osamu Matsuno, MD PURPOSE The presence of age-related pulmonary crackles (rales) might interfere 1Division of Internal Medicine, with a physician’s clinical management of patients with suspected heart failure. Nishida Hospital, Oita, Japan We examined the characteristics of pulmonary crackles among patients with stage A cardiovascular disease (American College of Cardiology/American Heart 2Division of Respiratory Disease, Oita University Hospital, Oita, Japan Association heart failure staging criteria), stratifi ed by decade, because little is known about these issues in such patients at high risk for congestive heart failure who have no structural heart disease or acute heart failure symptoms. METHODS After exclusion of comorbid pulmonary and other critical diseases, 274 participants, in whom the heart was structurally (based on Doppler echocar- diography) and functionally (B-type natriuretic peptide <80 pg/mL) normal and the lung (X-ray evaluation) was normal, were eligible for the analysis. RESULTS There was a signifi cant difference in the prevalence of crackles among patients in the low (45-64 years; n = 97; 11%; 95% CI, 5%-18%), medium (65-79 years; n = 121; 34%; 95% CI, 27%-40%), and high (80-95 years; n = 56; 70%; 95% CI, 58%-82%) age-groups (P <.001). The risk for audible crackles increased approximately threefold every 10 years after 45 years of age. During a mean fol- low-up of 11 ± 2.3 months (n = 255), the short-term (≤3 months) reproducibility of crackles was 87%. The occurrence of cardiopulmonary disease during follow-up included cardiovascular disease in 5 patients and pulmonary disease in 6. -

Nutrition Intake History

NUTRITION INTAKE HISTORY Date Patient Information Patient Address Apt. Age Sex: M F City State Zip Home # Work # Ext. Birthdate Cell Phone # Patient SS# E-Mail Single Married Separated Divorced Widowed Best time and place to reach you IN CASE OF EMERGENCY, CONTACT Name Relationship Home Phone Work Phone Ext. Whom may we thank for referring you? Work Information Occupation Phone Ext. Company Address Spouse Information Name SS# Birthdate Occupation Employer I verify that all information within these pages is true and accurate. _____________________________________ _________________________________________ _____________________ Patient's Signature Patient's Name - Please print Date Health History Height Weight Number of Children Are you recovering from a cold or flu? Are you pregnant? Reason for office visit: Date started: Date of last physical exam Practitioner name & contact Laboratory procedures performed (e.g., stool analysis, blood and urine chemistries, hair analysis, saliva, bone density): Outcome What types of therapy have you tried for this problem(s)? Diet modification Medical Vitamins/minerals Herbs Homeopathy Chiropractic Acupunture Conventional drugs Physical therapy Other List current health problems for which you are being treated: Current medications (prescription and/or over-the-counter): Major hospitalizations, surgeries, injuries. Please list all procedures, complications (if any) and dates: Year Surgery, illness, injury Outcome Circle the level of stress you are experiencing on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being the lowest): -

Assessing and Managing Lung Disease and Sleep Disordered Breathing in Children with Cerebral Palsy Paediatric Respiratory Review

Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 10 (2009) 18–24 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Paediatric Respiratory Reviews CME Article Assessing and managing lung disease and sleep disordered breathing in children with cerebral palsy Dominic A. Fitzgerald 1,3,*, Jennifer Follett 2, Peter P. Van Asperen 1,3 1 Department of Respiratory Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 2 Department of Physiotherapy, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 3 The Children’s Hospital at Westmead Clinical School, Discipline of Paediatrics & Child Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia EDUCATIONAL AIMS To appreciate the insidious evolution of suppurative lung disease in children with cerebral palsy (CP). To be familiar with the management of excessive oral secretions in children with CP. To understand the range of sleep problems that are more commonly seen in children with CP. To gain an understanding of the use of non-invasive respiratory support for the management of airway clearance and sleep disordered breathing in children with CP. ARTICLE INFO SUMMARY Keywords: The major morbidity and mortality associated with cerebral palsy (CP) relates to respiratory compromise. Cerebral palsy This manifests through repeated pulmonary aspiration, airway colonization with pathogenic bacteria, Pulmonary aspiration the evolution of bronchiectasis and sleep disordered breathing. An accurate assessment involving a Suppurative lung disease multidisciplinary approach and relatively simple interventions for these conditions can lead to Physiotherapy significant improvements in the quality of life of children with CP as well as their parents and carers. This Airway clearance techniques Obstructive sleep apnoea review highlights the more common problems and potential therapies with regard to suppurative lung Sleep disordered breathing disease and sleep disordered breathing in children with CP. -

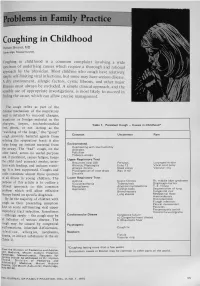

Problems in Family Practice

problems in Family Practice Coughing in Childhood Hyman Sh ran d , M D Cambridge, M assachusetts Coughing in childhood is a common complaint involving a wide spectrum of underlying causes which require a thorough and rational approach by the physician. Most children who cough have relatively simple self-limiting viral infections, but some may have serious disease. A dry environment, allergic factors, cystic fibrosis, and other major illnesses must always be excluded. A simple clinical approach, and the sensible use of appropriate investigations, is most likely to succeed in finding the cause, which can allow precise management. The cough reflex as part of the defense mechanism of the respiratory tract is initiated by mucosal changes, secretions or foreign material in the pharynx, larynx, tracheobronchial Table 1. Persistent Cough — Causes in Childhood* tree, pleura, or ear. Acting as the “watchdog of the lungs,” the “good” cough prevents harmful agents from Common Uncommon Rare entering the respiratory tract; it also helps bring up irritant material from Environmental Overheating with low humidity the airway. The “bad” cough, on the Allergens other hand, serves no useful purpose Pollution Tobacco smoke and, if persistent, causes fatigue, keeps Upper Respiratory Tract the child (and parents) awake, inter Recurrent viral URI Pertussis Laryngeal stridor feres with feeding, and induces vomit Rhinitis, Pharyngitis Echo 12 Vocal cord palsy Allergic rhinitis Nasal polyp Vascular ring ing. It is best suppressed. Coughs and Prolonged use of nose drops Wax in ear colds constitute almost three quarters Sinusitis of all illness in young children. The Lower Respiratory Tract Asthma Cystic fibrosis Rt. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Auscultation 4

Post-Acute COVID-19 Exercise & Rehabilitation (PACER) Project Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Examination By: Morgan Johanson, PT, MSPT, Board Certified Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Specialist Disclaimer • This course is intended for educational purposes and does not replace mentorship or consultation with more experienced cardiopulmonary colleagues. • This content is current at time of dissemination, however, realize that evidence and science on COVID19 is revolving rapidly and information is subject to change. Introduction and Disclosures • Morgan Johanson has no conflicts of interest or financial gains to disclose for this continuing education course • Course faculty: Morgan Johanson, PT, MSPT, Board Certified Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Specialist – President of Good Heart Education, a continuing education company providing live and online Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Therapy and Rehabilitation training and mentoring services for Physical Therapist studying for the ABPTS Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Specialty (CCS) Examination. – Adjunct Faculty Member, University of Toledo, Ohio – Practicing at Grand Traverse Pavilions SNF in Traverse City, MI – Professional Development Chair, CVP Section of the APTA Disclosures • Any pictures contained in the course that are not owned by Morgan Johanson were obtained via Google internet search engine and are references on the corresponding slide. Morgan Johanson does not claim ownership or rights to this material, it is being used for education purposes only and will not be reprinted or copied (so -

Johns Hopkins School of Nursing BURPS List

1 Welcome to the School of Nursing at the Johns Hopkins University! As a faculty who coordinates one of your first semester courses I am making available to you some helpful and useful information. I have included it below for your reading pleasure! There are two documents: the “B.U.R.P.S.” list (Building and Understanding Roots, Prefixes and Suffixes) and Talk like a Nurse. This document lists many (not all) of the medical terms used in your first semester classes and I believe will ease your transition into a new way of speaking. THE B.U.R.P.S LIST Purpose: To become proficient in Building and Understanding Roots, Prefixes and Suffixes Rationale: Building and understanding medical terminology is simpler when the words are broken down into roots, prefixes and suffixes. Steps: Review the B.U.R.P.S. tables and try to determine the definitions of the examples Notice the overlap among the three groups of roots, prefixes and suffixes Make new words by changing one part of the word. For example, if an appendectomy is the removal of the appendix, then a nephrectomy is the removal of a kidney. Tachycardia is a fast heart rate and tachypnea is a fast respiration rate. Helpful Note: R/T means “related to” TALK LIKE A NURSE Purpose: To become familiar with acronyms commonly used by health care providers Rationale: Different professions have unique languages; medicine and nursing are no exceptions. The acronyms below are used in verbal and written communication in health care settings. Steps: Review the attached list of acronyms (then you can start to critique shows like “House” and “Gray’s Anatomy” for accuracy!) Notice that some acronyms have two different meanings; e.g., ROM stands for “range of motion” and “rupture of membranes” - be careful when using abbreviations Take the Self Assessment after reading the approved terms, found in Blackboard NOTE: All institutions have a list of accepted and “do not use” abbreviations. -

Medical Terminology

MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM MATCHING EXERCISES ANATOMICAL TERMS 1. uvula a. little grapelike structure hanging above root 2. esophagus of tongue 3. cardiac sphincter b. tube carrying food from pharynx to stomach 4. jejunum c. cul de sac first part of large intestine 5. cecum d. empty second portion of small intestine e. lower esophageal circular muscle 1. ileum a. lower gateway of stomach that opens onto 2. ilium duodenum 3. appendix b. jarlike dilation of rectum just before anal 4. rectal ampulla canal 5. pyloric sphincter c. worm-shaped attachment at blind end of cecum d. bone on flank of pelvis e. lowest part of small intestine 1. peritoneum a. serous membrane stretched around 2. omentum abdominal cavity 3. duodenum b. inner layer of peritoneum 4. parietal peritoneum c. outer layer of peritoneum 5. visceral peritoneum d. first part of small intestine (12 fingers) e. double fold of peritoneum attached to stomach 1. sigmoid colon a. below the ribs' cartilage 2. bucca b. cheek 3. hypochondriac c. s-shaped lowest part of large intestine 4. hypogastric above rectum 5. colon d. below the stomach e. large intestine from cecum to anal canal SYMPTOMATIC AND DIAGNOSTIC TERMS 1. anorexia a. bad breath 2. aphagia b. inflamed liver 3. hepatomegaly c. inability to swallow 4. hepatitis d. enlarged liver 5. halitosis e. loss of appetite 1. eructation a. excess reddish pigment in blood 2. icterus b. liquid stools 3. hyperbilirubinemia c. vomiting blood MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 4. hematemesis d. belching 5. diarrhea e. jaundice 1. steatorrhea a. narrowing of orifice between stomach and 2. -

Signs and Symptoms of Oral Cancer

Signs and Symptoms of Oral Cancer l A sore in the mouth that does not heal l A white or red patch on the gums, tongue, tonsils or lining of the mouth l Pain, tenderness or numbness anywhere in your mouth or lip that does not go away l Trouble chewing or swallowing Quitting all forms of tobacco use is critical for good oral health and the prevention of serious or deadly diseases. Call the Mississippi Tobacco Quitline for free assistance to help you quit. 1-800-QUIT-NOW (1-800-784-8669) www.quitlinems.com MISSISSIPPI STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 5271 Revised 11-30-17 Tobacco doesn’t just stain your teeth and give you bad breath. Smoking and using spit tobacco are closely connected to tooth MOUTH – There is a strong link between cancer loss and cancer of the head and neck. Your risk of oral and of the mouth and tobacco use. About 75% of people throat cancer may be even greater if you use tobacco and with cancer of the mouth are tobacco users. drink alcohol frequently. TEETH – Spit tobacco use stains the teeth and may cause Any tobacco use can cause infections and diseases tooth pain and tooth loss. Spit tobacco is high in sugar in the mouth. Tobacco includes: and can also cause cavities. l Cigarettes LIPS – Spit tobacco use can cause sores and cancer l Cigars, pipes on the lip. l Little cigars, cigarillos l Snuff, dip, chew CHEEKS – Spit tobacco can cause white sores l E-cigarettes, vaping products on the inner lining of the mouth and tongue, which may turn to cancer.