Pure and Simple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

2020 Spr:Sum Mailchimp.Pdf

WELCOME We continue our season in 2020 with another great offereing of shows for you to enjoy. We have lots of exciting shows to suit all tastes and ages for you to laugh, sing, dance and enjoy starting with Total Pop Party. A new tribute to some of pops recent pop legends and a great way for younger fans to experience a pop BOOKING concert. For fans of comedy we have local icon CALL THE BOX OFFICE Billy Pearce performing at what will be a 01977 664566 sell out show, followed by Lee Lard with his tribute to Peter Kay. BOOK ONLINE www.castlefordphoenixtheatre.co.uk The students in the CAST return with their production of Our House - The EMAIL Musical. Packed with the music of [email protected] MADNESS this is a fresh, modern, romantic, musical sure to delight fans of POP IN (TERM-TIME ONLY) musicals. TUE, THU, FRI 4:30PM - 8:30PM SAT 10:00AM - 12:30PM Thank you to everyone who has liked and follows us on social media as we head The box office is also open from 1 hour before towards 3000 likes. We post the lastest every performance news, offers and info on social media so if you use Facebook, Twitter or Instagram Make a donation when booking tickets. A small just search for us, like and follow if you donation will help our ongoing fundraising. haven't already. KEEP UP TO DATE We hope you enjoy the seasons shows, Join our email list to receive regular updates please tell your friends and family if they with event information, special offers and more. -

18 0501 WFP A1 Tribute Poster 2 V2.Indd

PAUL McCARTNEY Boundless member exclusive Friday 18th January From his iconic role in the Beatles, to his successes in the 70’s this tribute will 2019 Tributes send you on a trip down memory lane. £10.00, Including 2 course dinner and Events Not a Boundless member? Visit boundless.co.uk/join-in to find out more TOM JONES MICHAEL JACKSON ABBA Friday 25th January Friday 17th May Friday 27th September A packed show full of all the classic hits Forever Jackson continues to perform A Tribute show to one of the greatest from the iconic star. globally, offering the closest experience and most successful pop groups of all £17.00, Including 2 course dinner to that of the original King of Pop. time. £20.00, Including 2 course dinner £20.00, Including 2 course dinner FREDDIE MERCURY GEORGE MICHAEL ELVIS Friday 1st February Friday 7th June Friday 4th October A nonstop energetic show to a legend Award winning tribute to the legendary From the Rock ‘n Roll of the 50’s, guaranteed to rock you. icon George Michael. through the movie years, to the 68’ £17.00, Including 2 course dinner £20.00, Including 2 course dinner Special, with the glitz of Las Vegas. £17.00, Including 2 course dinner WHAM DURAN NEIL DIAMOND STATUS QUO Friday 8th February Friday 14th June Friday 11th October Combining the two ultimate 80’s bands A Magical journey with Wayne Denton An adrenaline charged set crashes its in one blockbusting show! performing all of Neil Diamond’s hits. way through many of Quo’s 22 top ten £17.00, Including 2 course dinner £17.00, Including 2 course dinner chart hits. -

12/2008 Mechanical, Photocopying, Recording Without Prior Written Permission of Ukchartsplus

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in Issue 383 a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, 27/12/2008 mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Number 1 Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 7” Vinyl only Download only Pre-Release For the week ending 27 December 2008 TW LW 2W Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) High Wks 1 NEW HALLELUJAH - Alexandra Burke Syco (88697446252) 1 1 1 1 2 30 43 HALLELUJAH - Jeff Buckley Columbia/Legacy (88697098847) -- -- 2 26 3 1 1 RUN - Leona Lewis Syco ( GBHMU0800023) -- -- 12 3 4 9 6 IF I WERE A BOY - Beyoncé Columbia (88697401522) 16 -- 1 7 5 NEW ONCE UPON A CHRISTMAS SONG - Geraldine Polydor (1793980) 2 2 5 1 6 18 31 BROKEN STRINGS - James Morrison featuring Nelly Furtado Polydor (1792152) 29 -- 6 7 7 2 10 USE SOMEBODY - Kings Of Leon Hand Me Down (8869741218) 24 -- 2 13 8 60 53 LISTEN - Beyoncé Columbia (88697059602) -- -- 8 17 9 5 2 GREATEST DAY - Take That Polydor (1787445) 14 13 1 4 10 4 3 WOMANIZER - Britney Spears Jive (88697409422) 13 -- 3 7 11 7 5 HUMAN - The Killers Vertigo ( 1789799) 50 -- 3 6 12 13 19 FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK - The Pogues featuring Kirsty MacColl Warner Bros (WEA400CD) 17 -- 3 42 13 3 -- LITTLE DRUMMER BOY / PEACE ON EARTH - BandAged : Sir Terry Wogan & Aled Jones Warner Bros (2564692006) 4 6 3 2 14 8 4 HOT N COLD - Katy Perry Virgin (VSCDT1980) 34 -- -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Immediacy in Comedy: How Gertrude Stein, Long Form Improv, and 5 Second Films Can Revolutionize the Comedic Form

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2013 Immediacy In Comedy: How Gertrude Stein, Long Form Improv, And 5 Second Films Can Revolutionize The Comedic Form Alexander Hluch University of Central Florida Part of the Acting Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Hluch, Alexander, "Immediacy In Comedy: How Gertrude Stein, Long Form Improv, And 5 Second Films Can Revolutionize The Comedic Form" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2933. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2933 IMMEDIACY IN COMEDY: HOW GERTRUDE STEIN, LONG FORM IMPROV, AND 5 SECOND FILMS CAN REVOLUTIONIZE THE COMEDIC FORM by ALEX HLUCH M.A. in Theatre, Bowling Green State University, 2010 B.A. in Theatre, Ohio State University, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Acting in the department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 ABSTRACT Comedy has typically been derided as second-tier to drama in all aspects of narrative. Throughout history, comedy has seen short shrift in both critical reception and academic investigation. Merit is simply placed on drama far before that of comedy. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Devon in the First World War, 1914-1918

DEVON IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR WAR AND THE HOME FRONT: DEVON IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR, 1914-1918 By BONNIE WHITE, B.A. Hons., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Doctor ofPhilosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Bonnie White, October 2008 ii DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2008) McMaster University (History) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: War and the Home Front: Devon in the First World War AUTHOR: Bonnie White, B.A. Hons. (Saint Mary's University), MA. (University of New Brunswick SUPERVISOR(S): Dr. Stephen Heathom, Dr. Martin Hom NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 344 iii Abstract This investigation contributes to the existing scholarship on Britain and the First World War by examining the war's impact on the county of Devon in southwest England. More specifically, this study pays particular attention to how communities, families, and individuals responded to the pressures ofwar and to what extent social unity was achieved at the county level. By exploring the relationship between the state and its citizens, this dissertation questions the extent to which Devonians were passive and accepting of the sacrifices and hardships that the government required from them, how their experiences were informed, and to what extent class, gender, and religious differences limited public support for the war? While this dissertation argues that Devonians were generally supportive ofBritish participation in the war, that support was provisional and based on the perception of 'equality of sacrifice' - the expectation that the burdens ofwar would be shared equally throughout the county and across all segments of society. -

Celebrating 40 Years of Commercial Radio With

01 Cover_v3_.27/06/1317:08Page1 CELEBRATING 40 YEARS OF COMMERCIAL RADIOWITHRADIOCENTRE OFCOMMERCIAL 40 YEARS CELEBRATING 01 9 776669 776136 03 Contents_v12_. 27/06/13 16:23 Page 1 40 YEARS OF MUSIC AND MIRTH CONTENTS 05. TIMELINE: t would be almost impossible to imagine A HISTORY OF Ia history of modern COMMERCIAL RADIO music without commercial radio - and FROM PRE-1973 TO vice-versa, of course. The impact of TODAY’S VERY privately-funded stations on pop, jazz, classical, soul, dance MODERN BUSINESS and many more genres has been nothing short of revolutionary, ever since the genome of commercial radio - the pirate 14. INTERVIEW: stations - moved in on the BBC’s territory in the 1960s, spurring Auntie to launch RADIOCENTRE’S Radio 1 and Radio 2 in hasty response. ANDREW HARRISON From that moment to this, independent radio in the UK has consistently supported ON THE ARQIVAS and exposed recording artists to the masses, despite a changing landscape for AND THE FUTURE broadcasters’ own businesses. “I’m delighted that Music Week 16. MUSIC: can be involved in celebrating the WHY COMMERCIAL RadioCentre’s Roll Of Honour” RADIO MATTERS Some say that the days of true ‘local-ness’ on the UK’s airwaves - regional radio for regional people, pioneered by 18. CHART: the likes of Les Ross and Alan Robson - are being superseded by all-powerful 40 UK NO.1 SINGLES national brands. If that’s true, support for the record industry remains reassuringly OVER 40 YEARS robust in both corners of the sector. I’m delighted that Music Week can be involved in celebrating the RadioCentre’s 22. -

Hit Sheet 83

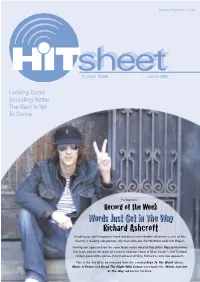

www.hitsheet.co.uk 7 JULY 2006 ISSUE #85 Looking Good, Sounding Better... The Best Is Yet To Come Parlophone Record of the Week WordsWords JustJust GetGet inin TheThe WayWay Richard Ashcroft Heading up our Parlophone front and back cover double whammy is one of this country’s leading songwriters, the man who put the Northern soul into Wigan. Having just appeared on the soon to be much missed Top of the Pops performing this track and on the back of a recent sold out show at Manchester’s Old Trafford cricket ground the genius (not madness) of King Richard is only too apparent. This is the 3rd hit to be released from the seminal Keys To The World album. Music Is Power and Break The Night With Colour were both hits, Words Just Get In The Way will be the hat-trick. 2 Hello and welcome to issue #85 of the Hit Sheet! So bird flu developed into world cup fever and we’re now left and should make her the superstar she deserves to be. as sick as parrots. If you look at my editorial last month I Meeting her afterwards was also a thrill as she was both predicted that England would lose on penalties in the quarter gorgeous and friendly! 31 The Birches, London, N21 1NJ finals and that Wayne Rooney would be sent off, so I wasn’t Finally, the Who gig in Hyde Park was fantastic, Pete too surprised. In my opinion England were doomed as soon Townshend’s guitar playing was an inspiration to all. -

Nominations in 2016 Leading Actor Ben Whishaw

NOMINATIONS IN 2016 LEADING ACTOR BEN WHISHAW London Spy – BBC Two IDRIS ELBA Luther – BBC One MARK RYLANCE Wolf Hall – BBC Two STEPHEN GRAHAM This is England ’90 – Channel 4 LEADING ACTRESS CLAIRE FOY Wolf Hall – BBC Two RUTH MADELEY Don’t Take My Baby – BBC Three SHERIDAN SMITH The C-Word – BBC One SURANNE JONES Doctor Foster – BBC One SUPPORTING ACTOR ANTON LESSER Wolf Hall – BBC Two CYRIL NRI Cucumber – Channel 4 IAN MCKELLEN The Dresser – BBC Two TOM COURTENAY Unforgotten - ITV SUPPORTING ACTRESS CHANEL CRESSWELL This is England ’90 – Channel 4 ELEANOR WORTHINGTON-COX The Enfield Haunting LESLEY MANVILLE River – BBC One MICHELLE GOMEZ Doctor Who – BBC One ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE GRAHAM NORTON The Graham Norton Show – BBC One LEIGH FRANCIS Celebrity Juice – ITV2 ROMESH RANGANATHAN Asian Provocateur – BBC Three STEPHEN FRY QI – BBC Two FEMALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME MICHAELA COEL Chewing Gum – E4 MIRANDA HART Miranda – BBC One SIAN GIBSON Peter Kay’s Car Share – BBC iPlayer SHARON HORGAN Catastrophe – Channel 4 MALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME HUGH BONNEVILLE W1A – BBC Two JAVONE PRINCE The Javone Prince Show – BBC Two PETER KAY Peter Kay’s Car Share –BBC iPlayer TOBY JONES Detectorists – BBC Four House of Fraser British Academy Television Awards – Nominations Page 1 SINGLE DRAMA THE C-WORD Susan Hogg, Simon Lewis, Nicole Taylor, Tim Kirkby – BBC Drama Production London/BBC One CYBERBULLY Richard Bond, Ben Chanan, David Lobatto, Leah Cooper – Raw TV/Channel 4 DON’T TAKE MY BABY Jack Thorne, Ben Anthony, Pier Wilkie,