Fort Mckay First Nation, Alberta Gabrielle Donnelly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2: Baseline, Section 13: Traditional Land Use September 2011 Volume 2: Baseline Studies Frontier Project Section 13: Traditional Land Use

R1 R24 R23 R22 R21 R20 T113 R19 R18 R17 R16 Devil's Gate 220 R15 R14 R13 R12 R11 R10 R9 R8 R7 R6 R5 R4 R3 R2 R1 ! T112 Fort Chipewyan Allison Bay 219 T111 Dog Head 218 T110 Lake Claire ³ Chipewyan 201A T109 Chipewyan 201B T108 Old Fort 217 Chipewyan 201 T107 Maybelle River T106 Wildland Provincial Wood Buffalo National Park Park Alberta T105 Richardson River Dunes Wildland Athabasca Dunes Saskatchewan Provincial Park Ecological Reserve T104 Chipewyan 201F T103 Chipewyan 201G T102 T101 2888 T100 Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park T99 1661 850 Birch Mountains T98 Wildland Provincial Namur River Park 174A 33 2215 T97 94 2137 1716 T96 1060 Fort McKay 174C Namur Lake 174B 2457 239 1714 T95 21 400 965 2172 T94 ! Fort McKay 174D 1027 Fort McKay Marguerite River 2006 Wildland Provincial 879 T93 771 Park 772 2718 2926 2214 2925 T92 587 2297 2894 T91 T90 274 Whitemud Falls T89 65 !Fort McMurray Wildland Provincial Park T88 Clearwater 175 Clearwater River T87Traditional Land Provincial Park Fort McKay First Nation Gregoire Lake Provincial Park T86 Registered Fur Grand Rapids Anzac Management Area (RFMA) Wildland Provincial ! Gipsy Lake Wildland Park Provincial Park T85 Traditional Land Use Regional Study Area Gregoire Lake 176, T84 176A & 176B Traditional Land Use Local Study Area T83 ST63 ! Municipality T82 Highway Stony Mountain Township Wildland Provincial T81 Park Watercourse T80 Waterbody Cowper Lake 194A I.R. Janvier 194 T79 Wabasca 166 Provincial Park T78 National Park 0 15 30 45 T77 KILOMETRES 1:1,500,000 UTM Zone 12 NAD 83 T76 Date: 20110815 Author: CES Checked: DC File ID: 123510543-097 (Original page size: 8.5X11) Acknowledgements: Base data: AltaLIS. -

Appendix 7: JRP SIR 69A Cultural Effects Review

October 2013 SHELL CANADA ENERGY Appendix 7: JRP SIR 69a Cultural Effects Review Submitted to: Shell Canada Energy Project Number: 13-1346-0001 REPORT APPENDIX 7: JRP SIR 69a CULTURAL EFFECTS REVIEW Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Report Structure .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Overview of Findings ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Shell’s Approach to Community Engagement ..................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Shell’s Support for Cultural Initiatives .................................................................................................................. 7 1.6 Key Terms ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6.1 Traditional Knowledge .................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6.2 Traditional -

Youth Attend Indspire Awards

A FORT MCKAY FIRST NATION PUBLICATION Current MARCH 2016 VOLUME 6 :: ISSUE 3 YOUTH ATTEND INDSPIRE AWARDS Fort McKay 3 Unity Days Trappers Training 4 Course a Success Fort McKay 7 Hockey Society Fort McKay & 8 Noralta Join Forces From left to right: Jaclyn Schick, Taylor McDonald, Nickita Black and Pat Flett. How to Talk to Your 9 Last month, E-Learning students their programs and scholarships. Kids About Drugs Nickita Black and Taylor Nickita and Taylor also found time McDonald were among students to explore the great city of from across Canada to attend the Vancouver with their chaperone 2016 Indspire Awards in Ona Fiddler-Berteig, who Vancouver, B.C., which included organized a bicycle ride through SAVE THE the accompanying Soaring: Stanley Park, an exploration of DATE: Indigenous Youth Career the Capilano Suspension Bridge, Conference. and, of course, an opportunity for The 10 year anniversary for shopping! the E-Learning program will Before the award show took place be celebrated on Saturday, May the girls attended various career During the awards show, the 26th. All 26 graduates will workshops and explored the girls were moved by the stories of receive invitations to attend and University of British Columbia. the award winners, from young a request for a guest list. Venue On a tour of the campus, the achievers just starting out to elders for this very special students were shown a special who have devoted their lives to the celebration will be announced door that only Aboriginal betterment of Indigenous peoples. soon. This event will be open graduates can use during During entertainment interludes, graduation ceremonies. -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems

National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems Alberta Regional Roll-Up Report FINAL Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development January 2011 Neegan Burnside Ltd. 15 Townline Orangeville, Ontario L9W 3R4 1-800-595-9149 www.neeganburnside.com National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems Alberta Regional Roll-Up Report Final Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Prepared By: Neegan Burnside Ltd. 15 Townline Orangeville ON L9W 3R4 Prepared for: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada January 2011 File No: FGY163080.4 The material in this report reflects best judgement in light of the information available at the time of preparation. Any use which a third party makes of this report, or any reliance on or decisions made based on it, are the responsibilities of such third parties. Neegan Burnside Ltd. accepts no responsibility for damages, if any, suffered by any third party as a result of decisions made or actions based on this report. Statement of Qualifications and Limitations for Regional Roll-Up Reports This regional roll-up report has been prepared by Neegan Burnside Ltd. and a team of sub- consultants (Consultant) for the benefit of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (Client). Regional summary reports have been prepared for the 8 regions, to facilitate planning and budgeting on both a regional and national level to address water and wastewater system deficiencies and needs. The material contained in this Regional Roll-Up report is: preliminary in nature, to allow for high level budgetary and risk planning to be completed by the Client on a national level. -

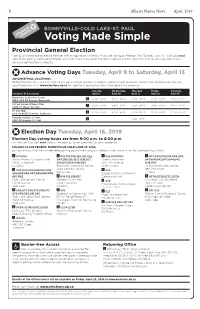

Voting Made Simple

8 Alberta Native News April, 2019 BONNYVILLE-COLD LAKE-ST. PAUL Voting Made Simple Provincial General Election Voting will take place to elect a Member of the Legislative Assembly. If you are voting on Election Day, Tuesday, April 16, 2019, you must vote at the polling station identified for you in the map. If you prefer to vote in advance, from April 9 to April 13, you may vote at any advance poll location in Alberta. Advance Voting Days Tuesday, April 9 to Saturday, April 13 ADVANCE POLL LOCATIONS Before Election Day, you may vote at any advance poll location in Alberta. Advance poll locations nearest your electoral division are specified below. Visit www.elections.ab.ca for additional polling locations throughout the province. Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Advance Poll Location April 9 April 10 April 11 April 12 April 13 Bonnyville Centennial Centre 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 1003, 4313 50 Avenue, Bonnyville St.Paul Senior Citizens Club 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 4809 47 Street, St. Paul Tri City Mall 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM Unit 20, 6503 51 Street, Cold Lake Portage College St. Paul 9 AM - 8 PM 5205 50 Avenue, St. Paul Election Day Tuesday, April 16, 2019 Election Day voting hours are from 9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. -

Challenge 2021

REDEVELOP Challenge 2021 VIRTUAL CONFERENCE SCHEDULE May 10-12, 2021 Training Canada’s future leaders in low-carbon energy … . … because Canada’s energy sector is changing. REDEVELOP.CA 2 Training across disciplines, distance and cultures. We Acknowledge the traditional territories of the people of the Treaty 7 region in Southern Alberta, which includes: the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina, and the Stoney Nakoda First Nations, including: the Chiniki, the Bearspaw, and the Wesley First Nations. Calgary is also home to the Metis Nation of Alberta Region III "Success comes from a combination of perseverance and having the right attitude." Chief Jim Boucher *Not intended for public distribution or for citation* 4th Annual REDEVELOP Challenge ∙ May 10 - 12, 2021 3 Welcome On behalf of our interdisciplinary team from the Universities of Calgary, Alberta, Toronto, Waterloo, and Western Ontario, I am pleased to welcome you to our 4th annual REDEVELOP Challenge. This is our 2nd conference using a virtual platform in this time of change in the energy-sector and during a global pandemic. REDEVELOP brings people together to work across disciplines, distance and cultures. Our collaborators from industry, government and Indigenous communities may have noticed that we rebranded last year, from a focus on the responsible development of low-permeability hydrocarbon resources to that of low-carbon energy resources; an adaptation to change. This week, you will hear from four innovative, multi-university teams of graduate students who will ask you to consider how this next generation of science, engineering and policy leaders will think about energy. Since 2017, we have trained 83 students at the graduate and undergraduate levels. -

Standing on Sacred Ground Series Profit and Loss Episode 56 Minutes Papua New Guinea 27 Minutes, Alberta Canada Tar Sands 29 Minutes

Standing on Sacred Ground series Profit and Loss episode 56 minutes Papua New Guinea 27 minutes, Alberta Canada Tar Sands 29 minutes This program includes subtitles and has an interactive transcript when viewed as part of the Global Environmental Justice Documentaries collection on Docuseek2. Video and lower thirds Name of speaker Audio and subtitles Timecode Montage of sacred sites visited music 00:00:01 throughout the series. Scenics of sacred sites in Peru, Narrator Graham You know them when you see them. 00:00:13 Australia, Ethiopia, Mt. Shasta and Greene Places on the earth that are set apart. Alberta. Places that transform us. Sacred places. Hunter doing animal call in the (Animal call) 00:00:29 woods. On-camera interview with Mike. Mike Mercredi When you're connected to the land and 00:00:33 everything that's out here then you know. Man paddling canoe in Papua New Y’know you don't own it, it owns you. Guinea (PNG). Montage of mines, pipelines and Narrator Graham But now, the relentless drive to exploit all 00:00:41 refineries in both PNG and Alberta Greene of the earth’s riches has thrust people cut with men paddling in PNG. across the globe into a struggle between ancient beliefs and industrial demand. On-camera interview with Winona Winona LaDuke Indigenous people are faced with the 00:00:54 LaDuke. largest mining corporations in the world – have been for years. Aerial shots of mining. Aerial scenics of PNG and pipeline. Narrator Graham In Papua New Guinea, villagers resist 00:01:02 Greene forced relocation and destruction of sacred sites. -

Zone a – Prescribed Northern Zones / Zones Nordiques Visées Par Règlement Place Names Followed by Numbers Are Indian Reserves

Northern Residents Deductions – Places in Prescribed Zones / Déductions pour les habitants de régions éloignées – Endroits situés dans les zones visées par règlement Zone A – Prescribed northern zones / Zones nordiques visées par règlement Place names followed by numbers are Indian reserves. If you live in a place that is not listed in this publication and you think it is in a prescribed zone, contact us. / Les noms suivis de chiffres sont des réserves indiennes. Communiquez avec nous si l’endroit où vous habitez ne figure pas dans cette publication et que vous croyez qu’il se situe dans une zone visée par règlement. Yukon, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories / Yukon, Nunavut et Territoires du Nord-Ouest All places in the Yukon, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories are located in a prescribed northern zone. / Tous les endroits situés dans le Yukon, le Nunavut et les Territoires du Nord-Ouest se trouvent dans des zones nordiques visées par règlement. British Columbia / Colombie-Britannique Andy Bailey Recreation Good Hope Lake Nelson Forks Tahltan Liard River 3 Area Gutah New Polaris Mine Taku McDames Creek 2 Atlin Hyland Post Niteal Taku River McDonald Lake 1 Atlin Park Hyland Ranch Old Fort Nelson Tamarack Mosquito Creek 5 Atlin Recreation Area Hyland River Park Pavey Tarahne Park Muddy River 1 Bear Camp Iskut Pennington Telegraph Creek One Mile Point 1 Ben-My-Chree Jacksons Pleasant Camp Tetsa River Park Prophet River 4 Bennett Kahntah Porter Landing Toad River Salmon Creek 3 Boulder City Kledo Creek Park Prophet River Trutch Silver -

Alberta, 2021 Province of Canada

Quickworld Entity Report Alberta, 2021 Province of Canada Quickworld Factoid Name : Alberta Status : Province of Canada Active : 1 Sept. 1905 - Present Capital : Edmonton Country : Canada Official Languages : English Population : 3,645,257 - Permanent Population (Canada Official Census - 2011) Land Area : 646,500 sq km - 249,800 sq mi Density : 5.6/sq km - 14.6/sq mi Names Name : Alberta ISO 3166-2 : CA-AB FIPS Code : CA01 Administrative Subdivisions Census Divisions (19) Division No. 11 Division No. 12 Division No. 13 Division No. 14 Division No. 15 Division No. 16 Division No. 17 Division No. 18 Division No. 19 Division No. 1 Division No. 2 Division No. 3 Division No. 4 Division No. 5 Division No. 6 Division No. 7 Division No. 8 Division No. 9 Division No. 10 Towns (110) Athabasca Banff Barrhead Bashaw Bassano Beaumont Beaverlodge Bentley Black Diamond Blackfalds Bon Accord Bonnyville Bow Island Bowden Brooks Bruderheim Calmar Canmore Cardston Carstairs Castor Chestermere Claresholm Coaldale Coalhurst Cochrane Coronation Crossfield Crowsnest Pass Daysland Devon Didsbury Drayton Valley Drumheller Eckville Edson Elk Point Fairview Falher © 2019 Quickworld Inc. Page 1 of 3 Quickworld Inc assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content of this document. The information contained in this document is provided on an "as is" basis with no guarantees of completeness, accuracy, usefulness or timeliness. Quickworld Entity Report Alberta, 2021 Province of Canada Fort MacLeod Fox Creek Gibbons Grande Cache Granum Grimshaw Hanna Hardisty High Level High Prairie High River Hinton Innisfail Killam Lac la Biche Lacombe Lamont Legal Magrath Manning Mayerthorpe McLennan Milk River Millet Morinville Mundare Nanton Okotoks Olds Oyen Peace River Penhold Picture Butte Pincher Creek Ponoka Provost Rainbow Lake Raymond Redcliff Redwater Rimbey Rocky Mountain House Sedgewick Sexsmith Slave Lake Smoky Lake Spirit River St. -

GOLD for WARRIORS Fort Mckay’S Hockey Players Have Community Awards 3 Brought Home the Gold, in Truck- Players Representing Fort Mckay Loads

A FORT MCKAY FIRST NATION PUBLICATION Current MAY 2014 VOLUME 5 :: ISSUE 5 GOLD FOR WARRIORS Fort McKay’s hockey players have Community Awards 3 brought home the gold, in truck- Players representing Fort McKay loads. on the Jr. novice team included: Pow Wow 4 Ashton Quintal, Noah Fitz- Every year kids from all over patrick, Tayden Shott, Keegan Historical Pics 6 the Wood Buffalo Region look Shott, Brayden Lacorde, Kayleigh Art by Jason Gladue forward to a weekend of Native Boucher, and Blaize Bouchier. 9 Hockey, the one weekend that The teams were coached by Si- On the River 10 friends and cousins often get mon Adams, who was assisted by to play together as a team. Six BJ Fitzpatrick and Cory Jackson. Oiler’s Camp 11 teams representing Wood Buffalo With three wins and one tie in Native Hockey Club travelled to their division, the youngest team Edmonton April 2-6th for the Al- brought home gold and a new berta Native Hockey Provincials. banner to hang in the Fort McKay Fort McKay registered kids in Arena. several age groups, with a major- ity registered in Jr. Novice and Sr. Players representing Fort McKay Novice as well as the Atom, Pee on the Sr. Novice team included: Wee, Bantam and Midget teams. (Continued on page 2) 5 11 3 1 HOCKEY STARS BRING HOME THE GOLD (Continued from page 1) The first championship banners to hang in the new arena. Fort McKay players from the Jayden Shott, Tyrese Shott, Exan- Joining this year’s Wood Buffalo Junior Novice 2014 Alberta Native Hockey Provincial der Lacorde, Kai Ro Grandjambe, teams also included: Championship team. -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background.