Natural Rights and the Founding Fathers-The Virginians, 17 Wash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

First Founding Father: Richard Henry Lee and the Call for Independence'

H-Nationalism Miller on Unger, 'First Founding Father: Richard Henry Lee and the Call for Independence' Review published on Monday, January 4, 2021 Harlow Giles Unger. First Founding Father: Richard Henry Lee and the Call for Independence. New York: Da Capo Press, 2017. 336 pp. $28.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-306-82561-3. Reviewed by Grace Miller (Independent Scholar) Published on H-Nationalism (January, 2021) Commissioned by Evan C. Rothera (University of Arkansas - Fort Smith) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54369 In First Founding Father, Harlow Giles Unger credits another historical figure with the founding of American democracy—Richard Henry Lee. Unger, a prolific scholar of US history, has published twenty-seven books, ten of which are biographies of the Founding Fathers. Through correspondence, autobiographies, memoirs, and relevant artwork, Unger brings Lee’s role and his experience during the American Revolution to life. Unger traces Lee’s life alongside the story of US independence and argues for the critical, yet unacknowledged, role that Lee played in uniting the thirteen colonies and shaping the first democratic government. Incorporating Lee into the pantheon of the Founding Fathers challenges a popular historical record, but also adds nuance and complexity to the story of US independence. First Founding Father contains a beginning, middle, and end of sorts: before the war, during the war, and after the war. During these critical phases, Unger makes clear that Richard Henry Lee was among the first to call for three important ideas—independence before the war, a union during the war, and a bill of rights after the war. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Honors Projects Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice Winter 2013 The irV ginia Statute for Religious Freedom: Revolutionary and Forgotten Ross L. Argir Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects Recommended Citation Argir, Ross L., "The irV ginia Statute for Religious Freedom: Revolutionary and Forgotten" (2013). Honors Projects. 189. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/189 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom: Revolutionary and Forgotten Ross L. Argir Frederik Meijer Honors College-Grand Valley State University HNR 499 Winter 2013 Advisor: Dr. Brent A. Smith Argir 1 Universal religious toleration and the separation of Church and State are two principles that many consider integral to the United States of America. However, few know the history behind these protections or their original intent, to protect religion from the state, or of the first law in which they were present, The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, authored by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the Virginia Legislature in 1786. This paper will examine the history behind the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, paying close attention to both the history of American Church and State relations prior to the Statute, and to the motives that its author and main proponent, Thomas Jefferson, had for drafting it. -

Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 8, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CITY OF SOUTHLAKE RANKED IN mother fell unconscious while on a shopping percent and helped save 1,026 lives. Blood TOP TEN trip. Bobby freed himself from the car seat and donors like Beth Groff truly give the gift of life. tried to help her. The young hero stayed calm, She has graciously donated 18 gallons of HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS showed an employee where his grandmother blood. OF TEXAS was, and gave valuable information to the po- John D. Amos II and Luis A. Perez were lice. While on his way to school, Mike two residents of Northwest Indiana who sac- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Spurlock came upon an accident scene. As- rificed their lives during Operation Iraqi Free- Tuesday, September 7, 2004 sisted by other heroic citizens, Mike broke out dom, and their deaths come as a difficult set- Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, it is my great one of the automobile’s windows and removed back to a community already shaken by the honor to recognize five communities within my the badly injured victim from the car. After the realities of war. These fallen soldiers will for- district for being acknowledged as among the incident, he continued on to school as usual to ever remain heroes in the eyes of this commu- ‘‘Top Ten Suburbs of the Dallas-Fort Worth take his final exam. nity, and this country. Area,’’ by D Magazine, a regional monthly The Red Cross is also recognizing the fol- I would like to also honor Trooper Scott A. -

Committees of Self Governance by Penny Waite

Carlyle House July, 2012 D OCENT D ISPATC H Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority Committees of Self Governance By Penny Waite Although the port of Alexandria did not experience formed May 26, 1773 to “consider the British battle during the Revolutionary War, it was a strategic claims as a common cause to all, and to produce a destination for much needed supplies to the colony. unity of action.” Governor Dunmore had John Carlyle’s stature as a successful merchant, dismissed the Assembly with bills undone. experienced commissary, and civic leader allowed Suspecting that Dunmore would suspend the revolutionary leaders, such as George Washington and Assembly again in 1774, the delegates were George Mason, to capitalize on his talents to help elected to meet in convention whether or not the further the Revolution. Though we know Carlyle was legislative session was dismissed by the Governor. not a young man, Edmund Randolph wrote, “The old who had seen service in the Indian War of 1755, roused Surely the prominent members of Alexandria were the young to resist the ministry.” During the abuzz with the uncertainty. A letter dated May 29, Revolutionary period, John Carlyle’s merchant activities 1774 was sent by the Committee of were significantly impacted by the trade embargo Correspondence for the Alexandria Town against England called for by the First Continental Committee and signed by John Carlyle and John Congress in 1774. Though most of the records and Dalton on behalf of eight other members. It states journals of the committees have been lost, we can get that the committee was “formed for the purpose of communicating to each other, in the most speedy manner, their sentiments on the present interesting and Alarming situation of America.” There was, in all probability, a secret element to the work of this committee and the committees formed by the local counties. -

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776. THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION of the thirteen united STATES OF AMERICA, WHEN in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.ÐWe hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.ÐThat to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,ÐThat whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.Ð Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Minutes of April 13, 2021 Board Meeting

1 April 13, 2021 The Wythe County Board of Supervisors held its regularly scheduled meeting at 6:00 p.m., Tuesday, April 13, 2021. The location of the meeting was in the Boardroom of the County Administration Building, 340 South Sixth Street, Wytheville, Virginia. MEMBERS PRESENT: Brian W. Vaught, Chair Coy L. McRoberts Ryan M. Lawson, Vice Chair James D. “Jamie” Smith Rolland R. Cook Stacy A. Terry B. G. “Gene” Horney, Jr. STAFF PRESENT: Stephen D. Bear, County Administrator Matthew C. Hankins, Assistant County Administrator Don Martin, Assistant County Attorney Jimmy McCabe, Emergency Services Coordinator Martha Collins, Administrative Assistant/Clerk OTHERS PRESENT: Kim Aker Lorna King Barry Ayers Ami Kirk Deanna Bradberry Linda Lacey Steve Canup Zach Lester Emily Cline Linda Meyer Mitchell Cook Cade Minton Tracey Crigger Dicky Morgan Noah Davis Megan Patrick James Fedderman Jonathan Powers Justin Felts Jo Repass Charlie Foster Lynn Rosenbaum Steve Goliher Chris Sizemore Amber Gravley Lachen Streeby Lori Guynn Donn Sunshine Dylan Jones and family Frances Watson Andy Kegley Joseph Wilkins Gus Kincer approximately five others 2 April 13, 2021 CALL TO ORDER Chair Vaught determined that a quorum was present and called the meeting to order at 6:00 p.m. The Chair also requested that everyone keep County Attorney Scot Farthing and his family in their prayers due to the recent loss of his father. INVOCATION AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Pastor Steve Canup, Fort Chiswell Church of Christ, provided the invocation and Supervisor Cook led the Pledge -

Fascinating Facts About the U.S. Constitution

The U.S. Constitution & Amendments: Fascinating Facts (Continued) Fascinating Facts About The U.S. Constitution The U.S. Constitution has 4,400 words. It is the The Constitution does not set forth requirements oldest and shortest written Constitution of any major for the right to vote. As a result, at the outset of government in the world. the Union, only male property-owners could vote. ___________________ African Americans were not considered citizens, and women were excluded from the electoral process. Of the spelling errors in the Constitution, Native Americans were not given the right to vote “Pensylvania” above the signers’ names is probably until 1924. the most glaring. ___________________ ___________________ James Madison, “the father of the Constitution,” Thomas Jefferson did not sign the Constitution. was the first to arrive in Philadelphia for the He was in France during the Convention, where Constitutional Convention. He arrived in February, he served as the U.S. minister. John Adams was three months before the convention began, bearing serving as the U.S. minister to Great Britain during the blueprint for the new Constitution. the Constitutional Convention and did not attend ___________________ either. ___________________ Of the forty-two delegates who attended most of the meetings, thirty-nine actually signed the Constitution. The Constitution was “penned” by Jacob Shallus, Edmund Randolph and George Mason of Virginia A Pennsylvania General Assembly clerk, for $30 and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts refused to ($726 today). sign in part due to the lack of a bill of rights. ___________________ ___________________ Since 1952, the Constitution has been on display When it came time for the states to ratify the in the National Archives Building in Washington, Constitution, the lack of any bill of rights was the DC. -

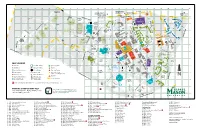

GMU-Fairfax-Campus-Map-2021.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z NO ENTRY NO EXIT EXIT NO Rapidan River Rd UNIVERSITY DRIVE TO: University Park Intramural Fields Mason Enterprise Center Commerce Building OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 TO: 4301 University Dr. 4087 University Dr. University Townhouse Complex 9 ROBERTS ROAD TO: 4260 Chain Bridge Rd. Tallwood 4210 Roberts Road R E V I KR C O N N A H A P P A 1 Student Townhouses 47 UNIVERSITY DRIVE UNIVERSITY DRIVE VE Reserved Parking GEORGE MASON BLVD S DR I PU M Field #1 LOT P A 35 C General Permit A Q 42 Parking U CO T S W OL I I D Rappahannock River A A S R H Parking Deck C C I 96 N L Spuhler Field L L LOT O R 38 L L D E 45 A A General Permit E 2 N O Mesocosm K R EVESHAM LANE E Parking Research BREDEN HILL LANE R L P ATRIOT CIRCLE Area A E PATRIOT CIRCLE N 39 V CHESAPEAKE RIVER LANE PERSHORE LANE I E R LOT M N Tennis CAMPUS DRIVE 23 97 Pilot A Softball General 63 62 Courts D House I Stadium Field House P Stadium Permit 98 D A Parking WEST CAMPUS WAY R LOT I Finley 61 3 Reserved Lot 69 OA Parking 34 S R 24 T Field #3 16 R Wotring 60 Courtyard 70 E OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 E B C A M P U S D R I V E L 56 C 65 STAFFORDSHIRE LANE R 20 I 71 51 49 RO C 21 BUFFALO CREEK CT T 58 72 4 O 33 Field #4 I 77 R 19 Maintenance T 64 WES T RAC A Storage Yard 6 Throwing CAMPUS DRIVE P 78 CA MPU S Fields Field 2 76 68 AY PA R K I N G 73 W LO T D 22 ROCKFISH CREEK LANE R 75 E Faculty/Staff Parking IV 74 R 53 66 8 57 SUB I NA Lot T N 5 5 31 E VA RIV 28 I CA US D AQUIA CREEK LANE R M P 67 Field #5 59 Y Kelly II A W NNA RI V E R 32 CAMPUS DRIVE A IV BRADDOCK ROAD/RT 620 PV LO T 10 R 27 KELLEY DRIVE General Parking 55 SHENANDOAH RIVER LANE 48 13 The Hub MASON POND DRVE 41 6 GLOBAL LANE RAC Mason Pond 25 Parking Deck BANISTER CREEK CT. -

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University?

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University? Make World-Changing Discoveries Tier 1 #14 1st Research Institute 1 of 81 Public Universities with Washington, DC, ranks #1 Carnegie Foundation's Tier 1 for the most STEM jobs in Highest Research Activity Most Innovative School a major US metro region (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education) (U.S. News & World Report 2017) (AIER College Destinations Index 2016) #22 #12 Safest Campus Most Diverse University in the US in the United States (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (National Council for Home Safety and Security 2017) Ranked #22 45 minutes Nationwide for Top Internship Opportunities Outside of Washington, DC (The Princeton Review 2016) Employability at George Mason University Mason graduates are employed by many top companies, including: 84% 76% Boeing Lockheed Martin of employed students of Mason students are Volkswagen Accenture are in positions related employed within six Freddie Mac Marriott International to their career goals months of graduation Ernst & Young IBM (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) 2 | INTO George Mason University 2018–2019 Top Programs GRADUATE #7 #17 #20 #27 Cybersecurity Special Education Criminology Systems Engineering (Ponemon Institute 2014) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) #33 #33 #64 #67 Economics Healthcare Public Policy Analysis Computer Science (U.S. News & World Report 2016) Management (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) UNIVERSITY* #68 #78 #110 #140 Top Public Best Undergraduate Best Undergraduate in National Schools Business Programs Engineering Programs Universities *U.S.