Incident Command 3Rd Edition 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Public Safety Emergency Planning and Response Solutions

Smart Public Safety Emergency Planning and Response Solutions A White Paper from Frost & Sullivan in Conjunction with Hexagon Safety & Infrastructure www.frost.com 50 Years of Growth, Innovation and Leadership Frost & Sullivan Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................3 Part 1: Introduction to state & provincial, regional, and local public safety emergency management .............................................................................................................4 Part 2: Overview of agency challenges, goals, and spending for emergency management planning applications .................................................................................................................5 Part 3: Emergency management solution case studies ..................................................................6 Part 4: Intergraph Planning & Response solution evaluation and assessment ...............................8 Part 5: The Last Word ................................................................................................................9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Smart Public Safety Emergency Planning and Response Solutions EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Planning for and responding to large-scale events and emergencies has never been more complex and unpredictable. National, state, provincial, and local organizations tasked with public safety must now contend with coordinating activities for entertainment events, natural disasters, industrial accidents, environmental -

London's Burning: Assessing the Impact of the 2014 Fire Station

IN BRIEF VISUALISATION London’s burning: Assessing the impact of the 2014 fire station closures What effect have fire station closures had on response times in central London?Benjamin M. Taylor investigates n the face of ongoing austerity To its credit, the LFB collects boroughs can be divided further into measures imposed by the British information on all call-outs – including wards; however, my analysis sought government, the consequences of the type of fire, date, time of day, spatial to understand the effect of the station Icuts to public services are beginning location and response time – which closures at the sub-ward level. to unfold. One of the most contentious allows researchers to analyse the impact Deciding which spatial areas may decisions taken in 2014 related to the that station closures have had. In fact, be at risk of increased response times closure of 10 fire stations and the loss in preparation for the closures, the Open Benjamin Taylor following the closures is not just a of 552 fire-fighters around the central Data Institute used this information to completed his question of producing maps of the London area. These measures were a work out that average response times PhD, “Sequential raw data. The time an engine takes result of the London Fire Brigade (LFB) across London were likely to increase Methodology with to respond to a call depends at what Applications in Sports being tasked with making savings of only marginally, from 5 min 34 s to 5 min Rating” at Lancaster time of day and on which day of the almost £29 million. -

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Operational Resilience/Special Operations Group Review

Report title Operational Resilience/Special Operations Group Review Report to Date Operations DB 29 July 2020 Transformation Directorate 11 August 2020 People Directorate 13 August 2020 Corporate Services DB 18 August 2020 Commissioner’s Board 26 August 2020 Deputy Mayor Fire and Resilience Board 8 September 2020 London Fire Commissioner Report by Report number Assistant Commissioner Control and Mobilising LFC-0406 Protective marking: NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Publication status: Published in full Summary This report sets out the key findings and subsequent recommendations from the Review of the Operational Resilience and Special Operations Group (OR/SOG) see Appendix 1. Recommendations That the London Fire Commissioner approves: a. The content and findings of the Review (Appendix 1). b. The recommendations of the Review. Background 1. London Fire Brigade (LFB) is one of the largest metropolitan fire and rescue services in the world and operates within a highly complex and challenging environment. The threat that emerged from international and domestic terror following the attacks in 2001 on the World Trade Centre and the subsequent challenges posed by Marauding Terrorist Attacks (MTA) has meant LFB has needed to ensure it is able to respond to these threats and mitigate their impact. As a result, the OR/SOG Department has provided the capability and expertise to deliver that response. This also included the development of a new tactical advisor role in 2001 with the creation of Interagency Liaison Officers (ILO) now National Interagency Liaison Officers (NILO). The instigation, development and coordination of the NILO role has been a significant achievement for LFB and enjoys substantial support across the fire and rescue sector and with partner agencies. -

Module 1: Preparedness, ICS, and Resources Topic 1

Module 1: Preparedness, ICS, and Resources Topic 1: Introduction Module introduction Narration Script: Becoming a wildland firefighter means you’ve got a lot to learn—and a lot of “prep” work to do. A wildland fire is a kind of classroom and everyday is like preparing for a new pop quiz. You’ll need to be physically ready and know how to maintain your stamina over the long haul with the right foods and fluids. You also need to know that you’ve brought along the right gear and that you’ve maintained it in tip-top shape to effectively fight the fire. You’ll need important personal items to make your time on the line more comfortable. And if you understand your role in the incident command system and the chain of command, you will have a positive impact on the incidents you respond to. Fighting fires requires lots of resources—from aerial support to heavy machinery cutting fireline—you’ll have to adapt to working on different crew types and with different types of people. So get prepared to jump into this module and learn the foundations of preparedness, the incident command system, and the many resources enlisted to fight a wildland fire. By the end of this module, we want you scoring an “A” on your real-world fireline exam. Module overview Before going out on the fireline, there are “i’s” to dot and “t’s” to cross. Preparing equipment and continuing your wildland firefighting education are on top of the list. This module will give you an overview of: • Common fire fighting terms and parts of a fire • Personal protective equipment (PPE) and how to keep it in tip-top shape • Ways to combat dehydration and fatigue • Incident command system (ICS) and how you fit in • Types of crews and the importance of respecting your co-workers Narration Script: There’s a lot to cover before you can go out on the fireline. -

History of Ics

INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM NATIONAL TRAINING CURRICULUM HISTORY OF ICS October 1994 I. Background of ICS II. Curriculum Design III. Companion Documents IV. Supporting Material V. Table of Modules I. Background of the Incident Command System (ICS) A. Need for a Common Incident Management System The complexity of incident management, coupled with the growing need for multi-agency and multifunctional involvement on incidents, has increased the need for a single standard incident management system that can be used by all emergency response disciplines. Factors affecting emergency management and which influence the need for a more efficient and cost-effective incident management system are listed below. Not all of these will apply to every incident. • Population growth and spread of urban areas. • Language and cultural differences. • More multijurisdictional incidents. • Legal changes mandating standard incident management systems and multi-agency involvement at certain incidents. • Shortage of resources at all levels, requiring greater use of mutual aid. • Increase in the number, diversity, and use of radio frequencies. • More complex and interrelated incident situations. • Greater life and property loss risk from natural and human- caused technological disasters. • Sophisticated media coverage demanding immediate answers and emphasizing response effectiveness. • More frequent cost-sharing decisions on incidents. These factors have accelerated the trend toward more complex incidents. Considering the fiscal and resource constraints of local, state and federal responders, the Incident Command System (ICS) is a logical approach for the delivery of coordinated emergency services to the public. B. History of ICS Development ICS resulted from the obvious need for a new approach to the problem of managing rapidly moving wildfires in the early 1970s. -

LFB Quarterly Performance Report – Quarter 1 2020/21

Decision title LFB Quarterly Performance Report – Quarter 1 2020/21 Recommendation by Decision Number Assistant Director, Strategy and Risk LFC-0397-D Protective marking: NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Publication status: Published in full Summary Report LFC-0397 presents the Brigade’s performance against the London Safety Plan as at the end of quarter one 2020/21 (data to the end of 30 June 2020). The report covers performance against budgets, key indicators, risks and projects Decision That the London Fire Commissioner approves report LFC-0937 and Appendix 1 (LFB Quarterly Performance report). Andy Roe This decision was remotely signed London Fire Commissioner Date on Wednesday 03 February Access to Information – Contact Officer Name Steven Adams Telephone 020 8555 1200 Email [email protected] The London Fire Commissioner is the fire and rescue authority for London Report title LLLFBQ uarterlyPerformanceReport –––QQQuarter 111202020 202020 ///222111 Report to Date Commissioner’s Board 29 July 2020 Report by Report number Assistant Director, Strategy and Risk LFC -0397 Protective marking: NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Publication status: Published in full Summary This paper presents the Brigade’s performance against the London Safety Plan as at the end of quarter one 2020/21 (data to the end of 30 June 2020). This report covers performance against budgets, key indicators, risks and projects. Recommendations That the London Fire Commissioner approves this report and Appendix 1 (LFB Quarterly Performance report) prior to publication. Background 1. This is the quarter one 2020/21 performance report covering the Brigade’s activities in terms of key decisions, financial information, performance against key indicators across the Brigade’s three aims, workforce composition, risks and projects, set out in more detail at Appendix 1. -

Fire and Emergency Services Training Infrastructure in the Country

Directorate General NDRF & Civil Defence (Fire) Ministry of Home Affairs East Block 7, Level 7, NEW DELHI, 110066, Fire Hazard and Risk Analysis in the Country for Revamping the Fire Services in the Country Final Report – Fire and Emergency Services Training Infrastructure in the Country November 2012 Submitted by RMSI A-8, Sector 16 Noida 201301, INDIA Tel: +91-120-251-1102, 2101 Fax: +91-120-251-1109, 0963 www.rmsi.com Contact: Sushil Gupta General Manager, Risk Modeling and Insurance Email:[email protected] Fire-Risk and Hazard Analysis in the Country Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................. 2 List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... 4 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 6 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 7 1 Fire and Emergency Trainings ....................................................................................... 9 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 1.2 Aim of Training ....................................................................................................... -

The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia

THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL TRUST OF AUSTRALIA 2015 Churchill Fellowship Report by Ms Bronnie Mackintosh PROJECT: This Churchill Fellowship was to research the recruitment strategies used by overseas fire agencies to increase their numbers of female and ethnically diverse firefighters. The study focuses on the three most widely adopted recruitment strategies: quotas, targeted recruitment and social change programs. DISCLAIMER I understand that the Churchill Trust may publish this report, either in hard copy or on the internet, or both, and consent to such publication. I indemnify the Churchill Trust against loss, costs or damages it may suffer arising out of any claim or proceedings made against the Trust in respect for arising out of the publication of any report submitted to the Trust and which the Trust places on a website for access over the internet. I also warrant that my Final Report is original and does not infringe on copyright of any person, or contain anything which is, or the incorporation of which into the Final Report is, actionable for defamation, a breach of any privacy law or obligation, breach of confidence, contempt of court, passing-off or contravention of any other private right or of any law. Date: 16th April 2017 1 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. Bronnie Mackintosh. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 PROGRAMME 6 JAPAN 9 HONG KONG 17 INDIA 21 UNITED KINGDOM 30 STAFFORDSHIRE 40 CAMBRIDGE 43 FRANCE 44 SWEDEN 46 CANADA 47 LONDON, ONTARIO 47 MONTREAL, QUEBEC 50 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 52 NEW YORK CITY 52 GIRLS FIRE CAMPS 62 LOS ANGELES 66 SAN FRANCISCO 69 ATLANTA 71 CONCLUSIONS 72 RECOMMENDATIONS 73 IMPLEMENTATION AND DISSEMINATION 74 2 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. -

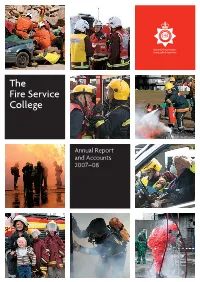

The Fire Service College Annual Report and Accounts 2007–08

K_\ =`i\J\im`Z\ :fcc\^\ 8eelXcI\gfik Xe[8ZZflekj )''.Æ'/ The Fire Service College Moreton-in-Marsh Annual Report and Accounts 2007–08 The Accounts of the Fire Service College as at 31st March 2008 presented pursuant to section 4(6) of the Government Trading Funds Act 1973 as amended by the Government Trading Act 1990 together with the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon. 21st July 2008 HC 858 London: Stationery Office Price: £18.55 The Fire Service College Annual Report and Accounts 2007–08 1234 Contents Introduction Management Commentary Chief Executive’s Foreword 4 (performance) Management Board 6 CLG executive agency 39 The College 8 Performance measurement 39 Management Commentary Accounts 2007–08 (business) Financial Report 43 The Fire Service College – role and remit 11 Notes to the Accounts 52 Meeting the needs of the UK Fire and 11 Annex A – Remuneration Report 2007–08 68 Rescue Service (FRS) Annex B – Statement on Internal Control 72 Support beyond the UK Fire and Rescue 11 for the Financial Year 2007–08 Service (FRS) A national College supporting national 12 and local needs Developments in key courses 15 International, commercial and public 22 sector training Organisational Development Centre 23 (ODC) summary Developments through the year 26 Governance and organisational structure 28 Communications 30 Environmental/social/community issues 33 Opportunities and challenges 36 Looking to the future 37 © Crown Copyright 2008 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. -

New Dimension— Enhancing the Fire and Rescue Services' Capacity to Respond to Terrorist and Other Large-Scale Incidents

House of Commons Public Accounts Committee New Dimension— Enhancing the Fire and Rescue Services' capacity to respond to terrorist and other large-scale incidents Tenth Report of Session 2008–09 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 9 February 2009 HC 249 [Incorporating HC 1184–i, Session 2007–08] Published on 12 March 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Public Accounts Committee The Committee of Public Accounts is appointed by the House of Commons to examine “the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and of such other accounts laid before Parliament as the committee may think fit” (Standing Order No 148). Current membership Mr Edward Leigh MP (Conservative, Gainsborough) (Chairman) Mr Richard Bacon MP (Conservative, South Norfolk) Angela Browning MP (Conservative, Tiverton and Honiton) Mr Paul Burstow MP (Liberal Democrat, Sutton and Cheam) Mr Douglas Carswell MP (Conservative, Harwich) Rt Hon David Curry MP (Conservative, Skipton and Ripon) Mr Ian Davidson MP (Labour, Glasgow South West) Angela Eagle MP (Labour, Wallasey) Nigel Griffiths MP (Labour, Edinburgh South) Rt Hon Keith Hill MP (Labour, Streatham) Mr Austin Mitchell MP (Labour, Great Grimsby) Dr John Pugh MP (Liberal Democrat, Southport) Geraldine Smith MP (Labour, Morecombe and Lunesdale) Rt Hon Don Touhig MP (Labour, Islwyn) Rt Hon Alan Williams MP (Labour, Swansea West) Phil Wilson MP (Labour, Sedgefield) The following member was also a member of the committee during the parliament. Mr Philip Dunne MP (Conservative, Ludlow) Powers Powers of the Committee of Public Accounts are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 148. -

Firefighter Foundation Development Programme

Firefighter Foundation Development Programme The Fire Service College In an ever changing environment where firefighters are facing new and challenging scenarios every day, the Fire Service College understands that firefighters at the start of their career need to be equipped with latest knowledge, skills and training in order for them to preform to their fullest. The Firefighter Foundation Development Programme (FFDP) is an intensive course focusing on laying the fundamental skills so that learners are able to safely attend operational incidents on completion of the programme. The course builds on developing the self-discipline, confidence, resilience and adaptability of the learners to underpin their first steps for a successful career in the fire and rescue service. Benefits of our FFDP: Provision of an accredited, recognisable and transferable Skills for Justice qualification Standardisation of training, meeting National Occupational Standards. Adherence with the demands and requirements of FRSs firefighter training and development Availability of night exercises Immersive scenarios Training at a world class incident ground Continuing professional development support Reduced training costs Flexible modular programme. 2 | telephone: +44(0)1608 812984 [email protected] | 3 Course content Our FFDP follows a modularised model, giving you the opportunity to decide the place, time and pace of delivery of training for both Wholetime and Retained Firefighters. You can also select additional content such as Water Responding or Safe Working at Height, enabling training to be tailored to your specific needs and delivered over a timeframe to suite you. Our standard FFDP course covers six fundamental modules, each with their own key learning outcomes: Basic Fire Ground Foundation Skills Breathing Apparatus and Tactical Ventilation Trauma Care and First Response Emergency Care Road Traffic Collision Hazardous Materials Scenario Exercises.