Real World Treatment Practices for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in Japan: an Observational Database Research Study (CLIMBER-DBR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Prospective, Multicenter, Phase-II Trial of Ibrutinib Plus Venetoclax In

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open HOVON 141 CLL Version 4, 20 DEC 2018 A prospective, multicenter, phase-II trial of ibrutinib plus venetoclax in patients with creatinine clearance ≥ 30 ml/min who have relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (RR-CLL) with or without TP53 aberrations HOVON 141 CLL / VIsion Trial of the HOVON and Nordic CLL study groups PROTOCOL Principal Investigator : Arnon P Kater (HOVON) Carsten U Niemann (Nordic CLL study Group)) Sponsor : HOVON EudraCT number : 2016-002599-29 ; Page 1 of 107 Levin M-D, et al. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e039168. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039168 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Levin M-D, et al. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e039168. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039168 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open HOVON 141 CLL Version 4, 20 DEC 2018 LOCAL INVESTIGATOR SIGNATURE PAGE Local site name: Signature of Local Investigator Date Printed Name of Local Investigator By my signature, I agree to personally supervise the conduct of this study in my affiliation and to ensure its conduct in compliance with the protocol, informed consent, IRB/EC procedures, the Declaration of Helsinki, ICH Good Clinical Practices guideline, the EU directive Good Clinical Practice (2001-20-EG), and local regulations governing the conduct of clinical studies. -

The New Therapeutic Strategies in Pediatric T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The New Therapeutic Strategies in Pediatric T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Marta Weronika Lato 1 , Anna Przysucha 1, Sylwia Grosman 1, Joanna Zawitkowska 2 and Monika Lejman 3,* 1 Student Scientific Society, Laboratory of Genetic Diagnostics, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (M.W.L.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Department of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Transplantology, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Genetic Diagnostics, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is a genetically heterogeneous cancer that ac- counts for 10–15% of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cases. The T-ALL event-free survival rate (EFS) is 85%. The evaluation of structural and numerical chromosomal changes is important for a comprehensive biological characterization of T-ALL, but there are currently no ge- netic prognostic markers. Despite chemotherapy regimens, steroids, and allogeneic transplantation, relapse is the main problem in children with T-ALL. Due to the development of high-throughput molecular methods, the ability to define subgroups of T-ALL has significantly improved in the last few years. The profiling of the gene expression of T-ALL has led to the identification of T-ALL subgroups, and it is important in determining prognostic factors and choosing an appropriate treatment. Novel therapies targeting molecular aberrations offer promise in achieving better first remission with the Citation: Lato, M.W.; Przysucha, A.; hope of preventing relapse. -

Draft Matrix Post Referral PDF 189 KB

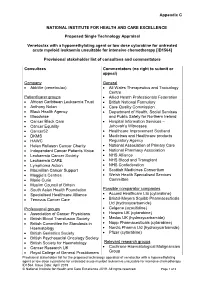

Appendix C NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE Proposed Single Technology Appraisal Venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent or low dose cytarabine for untreated acute myeloid leukaemia unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy [ID1564] Provisional stakeholder list of consultees and commentators Consultees Commentators (no right to submit or appeal) Company General • AbbVie (venetoclax) • All Wales Therapeutics and Toxicology Centre Patient/carer groups • Allied Health Professionals Federation • African Caribbean Leukaemia Trust • British National Formulary • Anthony Nolan • Care Quality Commission • Black Health Agency • Department of Health, Social Services • Bloodwise and Public Safety for Northern Ireland • Cancer Black Care • Hospital Information Services – • Cancer Equality Jehovah’s Witnesses • Cancer52 • Healthcare Improvement Scotland • DKMS • Medicines and Healthcare products • HAWC Regulatory Agency • Helen Rollason Cancer Charity • National Association of Primary Care • Independent Cancer Patients Voice • National Pharmacy Association • Leukaemia Cancer Society • NHS Alliance • Leukaemia CARE • NHS Blood and Transplant • Lymphoma Action • NHS Confederation • Macmillan Cancer Support • Scottish Medicines Consortium • Maggie’s Centres • Welsh Health Specialised Services • Marie Curie Committee • Muslim Council of Britain • South Asian Health Foundation Possible comparator companies • Specialised Healthcare Alliance • Accord Healthcare Ltd (cytarabine) • Tenovus Cancer Care • Bristol-Meyers Squibb Pharmaceuticals Ltd -

A Novel CDK9 Inhibitor Increases the Efficacy of Venetoclax (ABT-199) in Multiple Models of Hematologic Malignancies

Leukemia (2020) 34:1646–1657 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0652-0 ARTICLE Molecular targets for therapy A novel CDK9 inhibitor increases the efficacy of venetoclax (ABT-199) in multiple models of hematologic malignancies 1 1 2,3 4 1 5 6 Darren C. Phillips ● Sha Jin ● Gareth P. Gregory ● Qi Zhang ● John Xue ● Xiaoxian Zhao ● Jun Chen ● 1 1 1 1 1 1 Yunsong Tong ● Haichao Zhang ● Morey Smith ● Stephen K. Tahir ● Rick F. Clark ● Thomas D. Penning ● 2,7 3 5 1 4 2,7 Jennifer R. Devlin ● Jake Shortt ● Eric D. Hsi ● Daniel H. Albert ● Marina Konopleva ● Ricky W. Johnstone ● 8 1 Joel D. Leverson ● Andrew J. Souers Received: 27 November 2018 / Revised: 18 October 2019 / Accepted: 13 November 2019 / Published online: 11 December 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract MCL-1 is one of the most frequently amplified genes in cancer, facilitating tumor initiation and maintenance and enabling resistance to anti-tumorigenic agents including the BCL-2 selective inhibitor venetoclax. The expression of MCL-1 is maintained via P-TEFb-mediated transcription, where the kinase CDK9 is a critical component. Consequently, we developed a series of potent small-molecule inhibitors of CDK9, exemplified by the orally active A-1592668, with CDK selectivity profiles 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: that are distinct from related molecules that have been extensively studied clinically. Short-term treatment with A-1592668 rapidly downregulates RNA pol-II (Ser 2) phosphorylation resulting in the loss of MCL-1 protein and apoptosis in MCL-1- dependent hematologic tumor cell lines. This cell death could be attenuated by either inhibiting caspases or overexpressing BCL-2 protein. -

Access to High-Quality Oncology Care Across Europe

ACCESS TO HIGH-QUALITY ONCOLOGY CARE ACROSS EUROPE Thomas Hofmarcher, IHE Bengt Jönsson, Stockholm School of Economics IHE REPORT Nils Wilking, Karolinska Institutet and Skåne University Hospital 2014:2 Access to high-quality oncology care across Europe Thomas Hofmarcher IHE – The Swedish Institute for Health Economics, Lund, Sweden Bengt Jönsson Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm, Sweden Nils Wilking Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden and Skåne University Hospital, Lund/Malmö, Sweden IHE Report 2014:2 Print-ISSN 1651-7628 e-ISSN 1651-8187 The report can be downloaded from IHE’s website. Please cite this report as: Hofmarcher, T., Jönsson, B., Wilking, N., Access to high-quality oncology care across Europe. IHE Report. 2014:2, IHE: Lund. Box 2127 | Visit: Råbygatan 2 SE-220 02 Lund | Sweden Phone: +46 46-32 91 00 This report was commissioned and funded by Janssen Fax: +46 46-12 16 04 pharmaceutica NV and based on independent research delivered by IHE. Janssen has had no E-mail: [email protected] influence or editorial control over the content of this www.ihe.se report, and the views and opinions of the authors are Org nr 556186-3498 not necessarily those of Janssen. Vat no SE556186349801 Access to high-quality oncology care across Europe 2 Table of contents Executive Summary 4 6. Access to quality care in oncology – Treatment 57 1. Introduction 5 6.1. Review and summary of published studies 58 1.1. Purpose and scope of the report 5 6.1.1. Availability of new cancer drugs 58 1.2. The EU’s role in the fight against cancer 5 6.1.2. -

Systematic Identification and Assessment of Therapeutic Targets

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Systematic Identification and Assessment of Therapeutic Targets for Breast Cancer Based on Genome-Wide RNA Interference Transcriptomes Yang Liu 1,†, Xiaoyao Yin 2,†, Jing Zhong 3,†, Naiyang Guan 2, Zhigang Luo 2, Lishan Min 3, Xing Yao 3, Xiaochen Bo 4, Licheng Dai 3,* and Hui Bai 4,5,* 1 Research Center for Clinical & Translational Medicine, Beijing 302 Hospital, Beijing 100039, China; [email protected] 2 Science and technology on Parallel and Distributed Processing Laboratory, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha 410073, China; [email protected] (X.Y.); [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (Z.L.) 3 Huzhou Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Huzhou Central Hospital, Huzhou 313000, China; [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (X.Y.) 4 Beijing Institute of Radiation Medicine, Beijing 100850, China; [email protected] 5 No. 451 Hospital of PLA, Xi’an 710054, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.D.); [email protected] (H.B.); Tel.: +86-572-2555800 (L.D.); +86-010-66932251 (H.B.) † These authors contributed equally to this work Academic Editor: Wenyi Gu Received: 1 December 2016; Accepted: 13 February 2017; Published: 24 February 2017 Abstract: With accumulating public omics data, great efforts have been made to characterize the genetic heterogeneity of breast cancer. However, identifying novel targets and selecting the best from the sizeable lists of candidate targets is still a key challenge for targeted therapy, largely owing to the lack of economical, efficient and systematic discovery and assessment to prioritize potential therapeutic targets. -

Effects of Removing Reimbursement Restrictions on Targeted Therapy Accessibility for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment in Taiwan: an Interrupted Time Series Study

Open access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022293 on 15 March 2019. Downloaded from Effects of removing reimbursement restrictions on targeted therapy accessibility for non-small cell lung cancer treatment in Taiwan: an interrupted time series study Jason C Hsu, 1 Chen-Fang Wei,2 Szu-Chun Yang3 To cite: Hsu JC, Wei C-F, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Yang S-C. Effects of removing Interventions Targeted therapies have been proven to reimbursement restrictions provide clinical benefits to patients with metastatic non-small ► Both prescription rate and speed (time to prescrip- on targeted therapy cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Gefitinib was initially approved and accessibility for non-small tion) were used to measure drug accessibility. reimbursed as a third-line therapy for patients with advanced cell lung cancer treatment ► An interrupted time-series design, a strong qua- NSCLC by the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) in 2004; in Taiwan: an interrupted si-experimental method, was applied. subsequently it became a second-line therapy (in 2007) time series study. BMJ Open ► A segmented linear regression model was used to and further a first-line therapy (in 2011) for patients with 2019;9:e022293. doi:10.1136/ estimate postpolicy changes in both the level and epidermal growth factor receptor mutation-positive advanced bmjopen-2018-022293 trend of these study outcomes. NSCLC. Another targeted therapy, erlotinib, was initially ► Prepublication history for ► Data from the claims' database of the Taiwan approved as a third-line therapy in 2007, and it became a this paper is available online. -

Phenotype-Based Drug Screening Reveals Association Between Venetoclax Response and Differentiation Stage in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Acute Myeloid Leukemia SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Phenotype-based drug screening reveals association between venetoclax response and differentiation stage in acute myeloid leukemia Heikki Kuusanmäki, 1,2 Aino-Maija Leppä, 1 Petri Pölönen, 3 Mika Kontro, 2 Olli Dufva, 2 Debashish Deb, 1 Bhagwan Yadav, 2 Oscar Brück, 2 Ashwini Kumar, 1 Hele Everaus, 4 Bjørn T. Gjertsen, 5 Merja Heinäniemi, 3 Kimmo Porkka, 2 Satu Mustjoki 2,6 and Caroline A. Heckman 1 1Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland, Helsinki Institute of Life Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki; 2Hematology Research Unit, Helsinki University Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Center, Helsinki; 3Institute of Biomedicine, School of Medicine, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland; 4Department of Hematology and Oncology, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; 5Centre for Cancer Biomarkers, De - partment of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway and 6Translational Immunology Research Program and Department of Clinical Chemistry and Hematology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland ©2020 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol. 2018.214882 Received: December 17, 2018. Accepted: July 8, 2019. Pre-published: July 11, 2019. Correspondence: CAROLINE A. HECKMAN - [email protected] HEIKKI KUUSANMÄKI - [email protected] Supplemental Material Phenotype-based drug screening reveals an association between venetoclax response and differentiation stage in acute myeloid leukemia Authors: Heikki Kuusanmäki1, 2, Aino-Maija -

Sorafenib and Omacetaxine Mepesuccinate As a Safe and Effective Treatment for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Carrying Internal Tandem Du

Original Article Sorafenib and Omacetaxine Mepesuccinate as a Safe and Effective Treatment for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Carrying Internal Tandem Duplication of Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 3 Chunxiao Zhang, MSc1; Stephen S. Y. Lam, MBBS, PhD1; Garret M. K. Leung, MBBS1; Sze-Pui Tsui, MSc2; Ning Yang, PhD1; Nelson K. L. Ng, PhD1; Ho-Wan Ip, MBBS2; Chun-Hang Au, PhD3; Tsun-Leung Chan, PhD3; Edmond S. K. Ma, MBBS3; Sze-Fai Yip, MBBS4; Harold K. K. Lee, MBChB5; June S. M. Lau, MBChB6; Tsan-Hei Luk, MBChB6; Wa Li, MBChB7; Yok-Lam Kwong, MD 1; and Anskar Y. H. Leung, MD, PhD 1 BACKGROUND: Omacetaxine mepesuccinate (OME) has antileukemic effects against acute myeloid leukemia (AML) carrying an internal tandem duplication of Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3-ITD). A phase 2 clinical trial was conducted to evaluate a combina- tion treatment of sorafenib and omacetaxine mepesuccinate (SOME). METHODS: Relapsed or refractory (R/R) or newly diagnosed patients were treated with sorafenib (200-400 mg twice daily) and OME (2 mg daily) for 7 (first course) or 5 days (second course on- ward) every 21 days until disease progression or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). The primary endpoint was composite complete remission, which was defined as complete remission (CR) plus complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi). Secondary endpoints were leukemia-free survival (LFS) and overall survival (OS). RESULTS: Thirty-nine R/R patients and 5 newly diagnosed patients were recruited. Among the R/R patients, 28 achieved CR or CRi. Two patients showed partial remission, and 9 patients did not respond. -

Methotrexate 25 Mg/Ml Solution for Injection

METHOTREXATE 25 MG/ML SOLUTION FOR INJECTION (Methotrexate) PL 18727/0015 UKPAR TABLE OF CONTENTS Lay Summary Page 2 Scientific discussion Page 3 Steps taken for assessment Page 11 Steps taken after authorisation – summary Page 12 Summary of Product Characteristics Page 13 Product Information Leaflet Page 25 Labelling Page 27 MHRA PAR – Methotrexate 25 mg/ml Solution for Injection (PL 18727/0015) 1 - METHOTREXATE 25 MG/ML SOLUTION FOR INJECTION PL 18727/0015 LAY SUMMARY The MHRA granted Fresenius Kabi Oncology Plc a Marketing Authorisation (licence) for the medicinal product Methotrexate 25 mg/ml Solution for Injection on 22 November 2011. This product is a prescription-only medicine (POM). Methotrexate 25 mg/ml Solution for Injection is an antimetabolite medicine (medicine which affects the growth of body cells) and immunosuppressant (medicine which reduces the activity of the immune system). Methotrexate is used in large doses (on its own or in combination with other medicines) to treat certain types of cancer. In smaller doses it can be used to treat severe psoriasis (a skin disease with thickened patches of inflamed red skin, often covered by silvery scales), when it has not responded to other treatment. No new or unexpected safety concerns arose from this application and it was therefore judged that the benefits of taking Methotrexate 25 mg/ml Solution for Injection outweigh the risks and a Marketing Authorisation was granted. MHRA PAR – Methotrexate 25 mg/ml Solution for Injection (PL 18727/0015) 2 - METHOTREXATE 25 MG/ML SOLUTION -

Potential Biomarkers for Treatment Response to the BCL-2 Inhibitor Venetoclax: State of the Art and Future Directions

cancers Review Potential Biomarkers for Treatment Response to the BCL-2 Inhibitor Venetoclax: State of the Art and Future Directions Haneen T. Salah 1 , Courtney D. DiNardo 2 , Marina Konopleva 2 and Joseph D. Khoury 3,* 1 College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh 11533, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Department of Leukemia, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] (C.D.D.); [email protected] (M.K.) 3 Department of Hematopathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Apoptosis dysergulation is vital to oncogenesis. Efforts to mitigate this cancer hallmark have been ongoing for decades, focused mostly on inhibiting BCL-2, a key anti-apoptosis effector. The approval of venetoclax, a selective BCL-2 inhibitor, for clinical use has been a turning point in the field of oncology. While resulting in impressive improvement in objective outcomes, particularly for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma and acute myeloid leukemia, the use of venetoclax has exposed a variety of resistance mechanisms to BCL-2 inhibition. As the field continues to move forward, improved understanding of such mechanisms and the potential biomarkers that could be harnessed to optimize patient selection for therapies that include venetoclax and next-generation BCL-2 inhibitors are gaining increased importance. Abstract: Intrinsic apoptotic pathway dysregulation plays an essential role in all cancers, particularly hematologic malignancies. This role has led to the development of multiple therapeutic agents Citation: Salah, H.T.; DiNardo, C.D.; targeting this pathway. -

(INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances" WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1

INN Working Document 20.484 13/07/2020 Addendum1 to "The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances" WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Medicines and Health Products World Health Organization, Geneva © World Health Organization 2020 - All rights reserved. The contents of this document may not be reviewed, abstracted, quoted, referenced, reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated or adapted, in part or in whole, in any form or by any means, without explicit prior authorization of the WHO INN Programme. This document contains the collective views of the INN Expert Group and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the World Health Organization. Addendum1 to "The use of stem s in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances" - WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1 1 This addendum is a cumulative list of all new stems selected by the INN Expert Group since the publication of "The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances" 2018. -adenant adenosine receptors antagonists ciforadenant (118), preladenant (99), taminadenant (120), tozadenant (106), vipadenant (103) -caftor cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) protein modulators, correctors, and amplifiers bamocaftor (121), deutivacaftor (118), elexacaftor (121), galicaftor (119), icenticaftor (122), ivacaftor (104), lumacaftor (105), navocaftor (121), nesolicaftor