Growth Response of Giant Scallops to Periodicity of Flow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rainfall Thresholds for Flow Generation in Desert Ephemeral

Water Resources Research RESEARCH ARTICLE Rainfall Thresholds for Flow Generation 10.1029/2018WR023714 in Desert Ephemeral Streams 1 1 2 1 Key Points: Stephanie K. Kampf G!), Joshua Faulconer , Jeremy R. Shaw G!), Michael Lefsky , Rainfall thresholds predict 3 2 streamflow responses with high Joseph W. Wagenbrenner G!), and David J. Cooper G!) accuracy in small hyperarid and 1 2 semiarid watersheds Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA, Department 3 Using insufficient rain data usually of Forest and Rangeland Stewardship, Colorado State University, FortCollins, Colorado, USA, USDA Forest Service, Pacific increases threshold values for larger Southwest Research Station, Arcata, California,USA watersheds, leading to apparent scale dependence in thresholds Declines in flow frequency and Rainfall thresholds for streamflow generation are commonly mentioned in the literature, but increases in thresholds with drainage Abstract area are steeper in hyperarid than in studies rarely include methods for quantifying and comparing thresholds. This paper quantifies thresholds semiarid watersheds in ephemeral streams and evaluates how they are affected by rainfall and watershed properties. The study sites are in southern Arizona, USA; one is hyperarid and the other is semiarid. At both sites rainfall and 3 2 2 Supporting Information: streamflow were monitored in watersheds ranging from 10- to 10 km . Streams flowed an average of 0-5 • Supporting Information 51 times per year in hyperarid watersheds and 3-11 times per year in semiarid watersheds. Although hyperarid sites had fewer flow events, their flow frequency (fraction of rain events causing flow) was higher than in Correspondence to: 2 semiarid sites for small ( < 1 km ) watersheds. -

Coastal Erosion in Cape Cod, Massachusetts: Finding Sustainable Solutions Michael D

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Student Showcase Sustainable UMass 2015 Coastal Erosion in Cape Cod, Massachusetts: Finding Sustainable Solutions Michael D. Roberts University of Massachusetts - Amherst, [email protected] Lauren Bullard University of Massachusetts - Amherst Shaunna Aflague University of Massachusetts - Amherst Kelsi Sleet University of Massachusetts - Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/ sustainableumass_studentshowcase Part of the Environmental Policy Commons, and the Environmental Studies Commons Roberts, Michael D.; Bullard, Lauren; Aflague, Shaunna; and Sleet, Kelsi, "Coastal Erosion in Cape Cod, Massachusetts: indF ing Sustainable Solutions" (2015). Student Showcase. 6. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/sustainableumass_studentshowcase/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sustainable UMass at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Showcase by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coastal Erosion in Cape Cod 1 Coastal Erosion in Cape Cod, Massachusetts: Finding Sustainable Solutions Michael Roberts, Lauren Bullard, Shaunna Aflague, and Kelsi Sleet NRC 576 Water Resources Management and Policy Fall 2014 Coastal Erosion in Cape Cod 2 ABSTRACT The Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM) and the Cape Cod Planning Commission have identified coastal erosion, flooding, and shoreline change as the number one risk affecting the heavily populated 1,068 square kilometers that constitute Cape Cod (CZM, 2013 and Cape Cod Commission 2010). This paper investigates natural and anthropogenic causes for coastal erosion and their relationship with established social and economic systems. Sea level rise, climate change, and other anthropogenic changes increase the rate of coastal erosion. -

River Restoration and Chalk Streams

River Restoration and Chalk Streams Monday 22nd – Tuesday 23rd January 2001 University of Hertfordshire, College Lane, Hatfield AL10 9AB Organised by the River Restoration Centre in partnership with University of Hertfordshire Environment Agency, Thames Region Report compiled by: Vyv Wood-Gee Countryside Management Consultant Scabgill, Braehead, Lanark ML11 8HA Tel: 01555 870530 Fax: 01555 870050 E-mail: [email protected] Mobile: 07711 307980 ____________________________________________________________________________ River Restoration and Chalk Streams Page 1 Seminar Proceedings CONTENTS Page no. Introduction 3 Discussion Session 1: Flow Restoration 4 Discussion Session 2: Habitat Restoration 7 Discussion Session 3: Scheme Selection 9 Discussion Session 4: Post Project Appraisal 15 Discussion Session 5: Project Practicalities 17 Discussion Session 6: BAPs, Research and Development 21 Discussion Session 7: Resource Management 23 Discussion Session 8: Chalk streams and wetlands 25 Discussion Session 9: Conclusions and information dissemination 27 Site visit notes 29 Appendix I: Delegate list 35 Appendix II: Feedback 36 Appendix III: RRC Project Information Pro-forma 38 Appendix IV: Project summaries and contact details – listed 41 alphabetically by project name. ____________________________________________________________________________ River Restoration and Chalk Streams Page 2 Seminar Proceedings INTRODUCTION Workshop Objectives · To facilitate and encourage interchange of information, views and experiences between people working with projects and programmes with strong links to chalk streams and activities or research that affect this environment. · To improve the knowledge base on the practicalities and associated benefits of chalk stream restoration work in order to make future investments more cost effective. Participants The workshop was specifically targeted at individuals and organisations whose activities, research or interests include a specific practical focus on chalk streams. -

Report on the Millennium Chalk Streams Fly Trends Study

EA-South West/0fe2 s REPORT ON THE MILLENNIUM CHALK STREAMS FLY TRENDS STUDY A survey carried out in 2000 among 365 chalk stream fly fishermen, fishery owners, club secretaries and river keepers Subject: trends in aquatic fly abundance over recent decades and immediate past years, seen through the eyes of those constantly on the banks of, and caring for, the South country chalk rivers. Prepared by: Allan Frake, Environment Agency Peter Hayes, FMRS, Wiltshire Fishery Association with data available to all contributory associations and clubs. E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y WILTSHIRE FISHFRY ASSOCIATION I Report on the Millennium Chalk Streams Fly Trends Study Published by: Environment Agency Manley House Kestrel Way Exeter EX2 7LQ Tel: 01392 444000 Fax: 01392 444238 ISBN 1 85 705759 7 © Environment Agency 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the Environment Agency. En v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE SOUTH WEST REGION Manley House, Kestrel Way. Exeter EX2 7LQ SW-12/01 -E-1.5k-BG|W Errt-^o-t-Hv k Io i - i Report on the Millennium Chalk Streams Fly Trends Study I CONTENTS Management Summary Falling fly numbers Introduction and Objectives Methodology Sampling method, respondent qualifications and sample achieved Observational coverage Internal tests for bias, and robustness of data Questionnaire design -

Managing Catchments for Flood Risk and Biodiversity

How river catchments can be better managed to control flood risk and provide biodiversity benefits A critical discussion of options and experience and suggestions for ways forward Adam Broadhead and Julian Jones April 2010 Water21 (Department of Vision21 Ltd) 30 St Georges Place Cheltenham GL50 3JZ 01242 224321 Managing rivers and floodplains to reduce flood risk and improve biodiversity Abstract This paper critically discusses options for farmland, river and floodplain management to resolve flood risk and provide biodiversity benefits. Focusing on the UK context, where there is a call for working more closely with nature. Restoration of natural systems provides the best opportunities for habitat creation and biodiversity, but the benefits to flood risk management can be limited, unless applied at the catchment scale. Conventional hard-engineered approaches offer proven but expensive flood resolution, and there is now a move towards more soft-engineered, multi-purpose, low cost, naturalistic schemes involving the whole landscape. The effectiveness for biodiversity improvements must be balanced by the overriding priority to protect people from flooding. Linking biodiversity and flood risk management is an important step, but does not go far enough. Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Contents ................................................................................................................................................. -

Impacts of Watercress Farming on Stream Ecosystem Functioning and Community Structure

Impacts of watercress farming on stream ecosystem functioning and community structure. Cotter, Shaun The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/8385 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Impacts of watercress farming on stream ecosystem functioning and community structure Shaun Cotter School of Biological and Chemical Sciences Queen Mary, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London September 2012 1 Abstract. Despite the increased prominence of ecological measurement in fresh waters within recent national regulatory and legislative instruments, their assessment is still almost exclusively based on taxonomic structure. Integrated metrics of structure and function, though widely advocated, to date have not been incorporated into these bioassessment programmes. We sought to address this, by assessing community structure (macroinvertebrate assemblage composition) and ecosystem functioning (decomposition, primary production, and herbivory rates), in a series of replicated field experiments, at watercress farms on the headwaters of chalk streams, in southern England. The outfalls from watercress farms are typically of the highest chemical quality, however surveys have revealed long-term (30 years) impacts on key macroinvertebrate taxa, in particular the freshwater shrimp Gammarus pulex (L.), yet the ecosystem-level consequences remain unknown. -

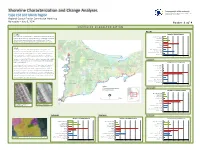

Cape Cod and Islands Region

Shoreline Characterization and Change Analyses Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Cape Cod and Islands Region Coastal Erosion Commission Regional Coastal Erosion Commission Workshop Barnstable – June 3, 2014 Poster 1 of 4 SHORELINE CHARACTERIZATION Bourne Description Bourne % of Assessed Shoreline Coastal landforms, habitats, developed lands, and hardened coastal structures (collectively referred to BULKHEAD/SEAWALL as “classes”) were identified at the immediate, exposed shoreline for coastal Massachusetts. Protected REVETMENT harbors and estuaries were generally excluded. Classes were identified for every ~50 meters of ALL STRUCTURES assessed shoreline and summarized by percentage of total assessed shoreline for each community. COASTAL BANK BEACH DUNE Methods S A LT M A R S H MAINTAINED OPEN SPACE A transect approach was used to identify classes along the shoreline. This approach allows us to NATURAL UPLAND examine features along any given ~50 m segment of shoreline. It provides more information at a finer NON - RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPED scale than one where areal coverage of features are summarized within a specified shoreline buffer. RESIDENTIAL Analysis can be expanded to include additional information on the order in which features occur moving landward, their landward extents, and the rates at which they co-occur along the shoreline. 0 20 40 60 80 100 Data sources include the 2011 USGS-CZM Shoreline Change Project's contemporary shoreline (MHHW) Sandwich and transect data, CZM and DCR's Coastal Structures Inventory data, MassDEP's Wetlands map data, and MassGIS's 2005 Land Use data. Sandwich % of Assessed Shoreline Shoreline Change Project transects generally occur every ~50 meters along exposed shoreline (Fig. -

Sediment Reduction Strategy for the Minnesota River Basin and South Metro Mississippi River

Sediment Reduction Strategy for the Minnesota River Basin and South Metro Mississippi River Establishing a foundation for local watershed planning to reach sediment TMDL goals. January 2015 Authors The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs by Larry Gunderson, MPCA using the Internet to distribute reports and Robert Finley, MPCA information to wider audience. Visit our web site Heather Bourne, LimnoTech for more information. Dendy Lofton, Ph.D., LimnoTech MPCA reports are printed on 100% post-consumer recycled content paper manufactured without Editing for final version: David Wall, Greg Johnson chlorine or chlorine derivatives. and Chris Zadak, MPCA Contributors/acknowledgements Gaylen Reetz, MPCA Scott MacLean, MPCA Justin Watkins, MPCA Greg Johnson, MPCA Chris Zadak, MPCA Wayne Anderson, MPCA Hans Holmberg, P.E., LimnoTech Al Kean, BWSR Shawn Schottler Ph.D., St. Croix Watershed Research Station Daniel R. Engstrom, Ph.D., St. Croix Watershed Research Station Craig Cox, Environmental Working Group Patrick Belmont, Ph.D., Utah State University Dave Bucklin, Cottonwood SWCD Paul Nelson, Scott Co. WMO Dave Craigmile Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | www.pca.state.mn.us | 651-296-6300 Toll free 800-657-3864 | TTY 651-282-5332 This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us Document number: wq-iw4-02 Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................................1 -

Transport and Deposition of Large Woody Debris in Streams: a Flume Experiment

ELSEVIER Geoinorphology 41 (2001) 263-283 www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Transport and deposition of large woody debris in streams: a flume experiment Christian A. Braudrick a, * , Gordon E. Grant a Department olGeosciences, Oregon State Unicersity, Corcallis, OR 97331, USA Pacific Northwest Research Station, US. Forest seruice, Cori:allis, OR 97331, USA Received 18 November 1998; received in revised form 21 February 2001 ; accepted 26 February 200 I Abstract Large woody debris (LWD) is an integral component of forested streams of the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere, yet little is known about how far wood is transported and where it is deposited in streams. In this paper, we report the results of flume experiments that examine interactions among hydraulics, channel geometry, transport distance and deposition of floating wood. These experiments were carried out in a 1.22-m-wide X 9.14-m-long gravel bed flume using wooden dowels of various sizes as surrogate logs. Channel planforins were either self-formed or created by hand, and ranged from meanders to alternate bars. Floating pieces tended to orient with long axes parallel to flow in the center of the channel. Pieces were deposited where channel depth was less than buoyant depth, typically at the head of mid-channel bars, in shallow zones where flow expanded, and on the outside of bends. We hypothesize that the distance logs travel may be a function of the channel’s debris roughness, a dimensionless index incorporating ratios of piece length and diameter to channel width, depth and sinuosity. Travel distance decreased as the ratio of piece length to both channel width and radius of curvature increased, but the relative importance of these variables changed with channel planform. -

Responses of Coral Reef Community Metabolism in Flumes to Ocean Acidification

Marine Biology (2018) 165:66 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-018-3324-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Responses of coral reef community metabolism in flumes to ocean acidification R. C. Carpenter1 · C. A. Lantz1,2 · E. Shaw1 · P. J. Edmunds1 Received: 4 June 2017 / Accepted: 8 March 2018 / Published online: 17 March 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Much of the research on the effects of ocean acidification on tropical coral reefs has focused on the calcification rates of individual coral colonies, and less attention has been given to carbonate production and dissolution at the community scale. Using flumes (5.0 × 0.3 × 0.3 m) located outdoors in Moorea, French Polynesia, we assembled local back reef communities with ~ 25% coral cover, and tested their response to pCO2 levels of 344, 633, 870 and 1146 μatm. Incubations began in late G P Austral spring (November 2015), and net community calcification ( net) and net community primary production ( net) were measured prior to treatments, 24 h after treatment began, and biweekly or monthly thereafter until early Austral autumn G (March 2016). net was depressed under elevated pCO2 over 4 months, although the magnitude of the response varied over G Ω Ω time. The proportional decline in net as a function of saturation state of aragonite ( ar) depended on the initial ar, but was Ω Ω 24% for a decline in ar from 4.0 to 3.0, which is nearly twice as sensitive to variation in ar than the previously published G Ω values for the net calcification of ex situ coral colonies. -

Bourne, MA | 2015 Annual Report | NPDES Phase II Small MS4 General Permit

Municipality/Organization: Town of Bourne EPA NPDES Permit Number: MAR041094 MaDEP Transmittal Number: W-040428 Annual Report Number & Reporting Period: No.12: April 1, 2014-March 31, 2015 NPDES PII Small MS4 Genera) Permit Annual Report Part I. General Information Contact Person: Mr. Thomas Guerino Title: Town Administrator Telephone #: (508) 759-0600 Email: [email protected] Certification: I certify under penalty oflaw that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnel properly gather and evaluate the information submitted. Based on my inquiry ofthe person or persons who manage the system, or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information, the information submitted is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, true, accurate, and complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting false information, including the possibility of fine and imprisonment for knowing violations. Signarure :d 71~,___ Title: ----/ A I __/ 1 P'U.-dY ~/I'll/ 7k4 ·re, .........___ 7 Date: <-/./3 /;7 Report 12 - Due May 1, 2015 Part II. Self-Assessment The Town of Bourne has completed the required self-assessment on the annual compliance review for the Phase II Storm water Program. Our municipality is working towards compliance, however proving difficult. The Town has worked with a consultant to draft a comprehensive bylaw, however in the opinion of the working group this version of the bylaw would not be feasible to enforce. The Town’s staff stormwater working group has worked with the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program staff Bernie Taber and John Rockwell to revise the Subdivision control bylaw as a first phase to implementation to compliance. -

Chalk Rivers-EN-Ea001a

l L l L L [ Chalk rivers l nature c~nservation and management I [ l L l [ L [ L ~ L L L L ~ =?\J ENVIRONMENT L G ENGLISH ~~. AGENCY for life [ NATURE L Chalk rivers nature conservation and management March 1999 CP Mainstone Water Research Centre Produced on behalf of English Nature and the Environment Agency (English Nature contract number FIN/8.16/97-8) Chalk rivers - nature conservation and management Contributors: NT Holmes Alconbury Environmental Consultants - plants PD Armitage Institute of Freshwater Ecology - invertebrates AM Wilson, JH Marchant, K Evans British Trust for Ornithology - birds D Solomon - fish D Westlake - algae 2 Contents Background 8 1. Introduction 9 2. Environmental characteristics of chalk rivers 12 2.1 Characteristic hydrology 12 2.2 Structural development and definition of reference conditions for conservation management 12 2.3 Characteristic water properties 17 3. Characteristic wildlife communities ofchalk rivers 20 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 Higher plants 25 3.3 Algae 35 3.4 Invertebrates 40 3.5 Fish 47 3.6 Birds 53 3.7 Mammals 58 4. Habitat requirements of characteristic wildlife communities 59 4.1 Introduction 59 4.2 Higher plants 59 4.3 Invertebrates 64 4.4 Fish 70 4.5 Birds 73 4.6 Mammals 79 4.7 Summary of the ecological requirements ofchalk river communities 80 5. Human activities and their impacts 83 5.1 The inherent vulnerability of chalk rivers 83 5.2 An inventory of activities and their links to ecological impact 83 5.3 Channel modifications and riverlfloodplain consequences 89 5.4 Low flows 92 5.5 Siltation 95 5.6 Nutrient enrichment 101 5.7 Hindrances to migration 109 5.8 Channel maintenance 109 5.9 Riparian management 115 5.10 Manipulation of fish populations 116 5.11 Bird species of management concern 119 5.12 Decline of the native crayfish 120 5.13 Commercial watercress beds as a habitat 121 5.14 Spread of non-native plant species 121 3 6.