Chapter 2. R As a Calculator: Order of Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Calculation Policy ÷

Mathematics Calculation Policy ÷ Commissioned by The PiXL Club Ltd. June 2016 This resource is strictly for the use of member schools for as long as they remain members of The PiXL Club. It may not be copied, sold nor transferred to a third party or used by the school after membership ceases. Until such time it may be freely used within the member school. All opinions and contributions are those of the authors. The contents of this resource are not connected with nor endorsed by any other company, organisation or institution. © Copyright The PiXL Club Ltd, 2015 About PiXL’s Calculation Policy • The following calculation policy has been devised to meet requirements of the National Curriculum 2014 for the teaching and learning of mathematics, and is also designed to give pupils a consistent and smooth progression of learning in calculations across the school. • Age stage expectations: The calculation policy is organised according to age stage expectations as set out in the National Curriculum 2014 and the method(s) shown for each year group should be modelled to the vast majority of pupils. However, it is vital that pupils are taught according to the pathway that they are currently working at and are showing to have ‘mastered’ a pathway before moving on to the next one. Of course, pupils who are showing to be secure in a skill can be challenged to the next pathway as necessary. • Choosing a calculation method: Before pupils opt for a written method they should first consider these steps: Should I use a formal Can I do it in my Could I use -

An Arbitrary Precision Computation Package David H

ARPREC: An Arbitrary Precision Computation Package David H. Bailey, Yozo Hida, Xiaoye S. Li and Brandon Thompson1 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720 Draft Date: 2002-10-14 Abstract This paper describes a new software package for performing arithmetic with an arbitrarily high level of numeric precision. It is based on the earlier MPFUN package [2], enhanced with special IEEE floating-point numerical techniques and several new functions. This package is written in C++ code for high performance and broad portability and includes both C++ and Fortran-90 translation modules, so that conventional C++ and Fortran-90 programs can utilize the package with only very minor changes. This paper includes a survey of some of the interesting applications of this package and its predecessors. 1. Introduction For a small but growing sector of the scientific computing world, the 64-bit and 80-bit IEEE floating-point arithmetic formats currently provided in most computer systems are not sufficient. As a single example, the field of climate modeling has been plagued with non-reproducibility, in that climate simulation programs give different results on different computer systems (or even on different numbers of processors), making it very difficult to diagnose bugs. Researchers in the climate modeling community have assumed that this non-reproducibility was an inevitable conse- quence of the chaotic nature of climate simulations. Recently, however, it has been demonstrated that for at least one of the widely used climate modeling programs, much of this variability is due to numerical inaccuracy in a certain inner loop. When some double-double arithmetic rou- tines, developed by the present authors, were incorporated into this program, almost all of this variability disappeared [12]. -

Neural Correlates of Arithmetic Calculation Strategies

Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 2009, 9 (3), 270-285 doi:10.3758/CABN.9.3.270 Neural correlates of arithmetic calculation strategies MIRIA M ROSENBERG -LEE Stanford University, Palo Alto, California AND MARSHA C. LOVETT AND JOHN R. ANDERSON Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Recent research into math cognition has identified areas of the brain that are involved in number processing (Dehaene, Piazza, Pinel, & Cohen, 2003) and complex problem solving (Anderson, 2007). Much of this research assumes that participants use a single strategy; yet, behavioral research finds that people use a variety of strate- gies (LeFevre et al., 1996; Siegler, 1987; Siegler & Lemaire, 1997). In the present study, we examined cortical activation as a function of two different calculation strategies for mentally solving multidigit multiplication problems. The school strategy, equivalent to long multiplication, involves working from right to left. The expert strategy, used by “lightning” mental calculators (Staszewski, 1988), proceeds from left to right. The two strate- gies require essentially the same calculations, but have different working memory demands (the school strategy incurs greater demands). The school strategy produced significantly greater early activity in areas involved in attentional aspects of number processing (posterior superior parietal lobule, PSPL) and mental representation (posterior parietal cortex, PPC), but not in a numerical magnitude area (horizontal intraparietal sulcus, HIPS) or a semantic memory retrieval area (lateral inferior prefrontal cortex, LIPFC). An ACT–R model of the task successfully predicted BOLD responses in PPC and LIPFC, as well as in PSPL and HIPS. A central feature of human cognition is the ability to strategy use) and theoretical (parceling out the effects of perform complex tasks that go beyond direct stimulus– strategy-specific activity). -

Banner Human Resources and Position Control / User Guide

Banner Human Resources and Position Control User Guide 8.14.1 and 9.3.5 December 2017 Notices Notices © 2014- 2017 Ellucian Ellucian. Contains confidential and proprietary information of Ellucian and its subsidiaries. Use of these materials is limited to Ellucian licensees, and is subject to the terms and conditions of one or more written license agreements between Ellucian and the licensee in question. In preparing and providing this publication, Ellucian is not rendering legal, accounting, or other similar professional services. Ellucian makes no claims that an institution's use of this publication or the software for which it is provided will guarantee compliance with applicable federal or state laws, rules, or regulations. Each organization should seek legal, accounting, and other similar professional services from competent providers of the organization's own choosing. Ellucian 2003 Edmund Halley Drive Reston, VA 20191 United States of America ©1992-2017 Ellucian. Confidential & Proprietary 2 Contents Contents System Overview....................................................................................................................... 22 Application summary................................................................................................................... 22 Department work flow................................................................................................................. 22 Process work flow...................................................................................................................... -

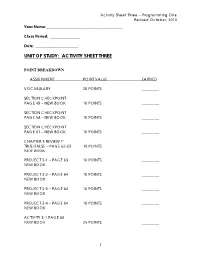

Unit of Study: Activity Sheet Three

Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 Your Name:_______________________________________ Class Period: _______________ Date: ______________________ UNIT OF STUDY: ACTIVITY SHEET THREE POINT BREAKDOWN ASSIGNMENT POINT VALUE EARNED VOCABULARY 20 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 49 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 54 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 61 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ CHAPTER 3 REVIEW ?’ TRUE/FALSE – PAGE 62-63 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-1 – PAGE 63 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-2 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-3 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-4 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK ACTIVITY 3-1 PAGE 66 NEW BOOK 25 POINTS _________ 1 Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 PURPLE BOOK LESSON 3 WRITTEN QUESTIONS 14 POINTS _________ Page 125 LESSON 3 PROJ.3-1 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-2 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-3 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-5 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ3-7 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-9 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-10 10 POINTS _________ CRITICAL THINKING 3-1 Essay 25 POINTS _________ **The topic has changed – see inside of packet for change TOTAL POINTS POSSIBLE 234 _________ GENERAL COMMENTS… 2 Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 YOUR NAME: CLASS PERIOD: Activity Sheet One - This activity will incorporate reading and activities from Fundamentals of C++ (Introductor y) and, Introduction to Computer Science Using C++. Both books can be found in the Programming area of the classroom, and must be returned at the end of the period. -

Ball Green Primary School Maths Calculation Policy 2018-2019

Ball Green Primary School Maths Calculation Policy 2018-2019 Contents Page Contents Page Rationale 1 How do I use this calculation policy? 2 Early Years Foundation Stage 3 Year 1 5 Year 2 8 Year 3 11 Year 4 14 Year 5 17 Year 6 20 Useful links 23 1 Maths Calculation Policy 2018– 2019 Rationale: This policy is intended to demonstrate how we teach different forms of calculation at Ball Green Primary School. It is organised by year groups and designed to ensure progression for each operation in order to ensure smooth transition from one year group to the next. It also includes an overview of mental strategies required for each year group [Year 1-Year 6]. Mathematical understanding is developed through use of representations that are first of all concrete (e.g. base ten, apparatus), then pictorial (e.g. array, place value counters) to then facilitate abstract working (e.g. columnar addition, long multiplication). It is important that conceptual understanding, supported by the use of representation, is secure for procedures and if at any point a pupil is struggling with a procedure, they should revert to concrete and/or pictorial resources and representations to solidify understanding or revisit the previous year’s strategy. This policy is designed to help teachers and staff members at our school ensure that calculation is taught consistently across the school and to aid them in helping children who may need extra support or challenges. This policy is also designed to help parents, carers and other family members support children’s learning by letting them know the expectations for their child’s year group and by providing an explanation of the methods used in our school. -

The Order of Operations Agreement Page 1

Lecture Notes The Order of Operations Agreement page 1 The order of operations rule is an agreement among mathematicians, it simplies notation. P stands for parentheses, E for exponents, M and D for multiplication and division, A and S for addition and subtraction. Notice that M and D are written next to each other. This is to suggest that multiplication and division are equally strong. Similarly, A and S are positioned to suggest that addition and subtraction are equally strong. This is the hierarchy, and there are two basic rules. 1. Between two operations that are on different levels of the hierarchy, we start with the operation that is higher. For example, between a division and a subtraction, we start with the division since it is higher in the hierarchy than subtraction. 2. Between two operations that are on the same level of the hierarchy, we start with the operation that comes rst from reading left to right. Example 1. Perform the indicated operations. 20 3 4 Solution: We observe two operations, a subtraction and a multiplication. Multiplication is higher in the hierarchy than subtraction, so we start there. 20 3 4 = multiplication 20 12 = subtraction = 8 Example 2. Perform the indicated operations. 36 3 2 Solution: It is a common mistake to start with the multiplication. The letters M and D are in the same line because they are equally strong; among them we proceed left to right. From left to right, the division comes rst. 36 3 2 = division 12 2 = multiplication = 24 Example 2v. Perform the indicated operations. -

Calculation Devices

Type 2 Calculation Devices Description of Accommodation This accommodation provides an alternate method of computation for a student with a disability who is unable to effectively use paper-and-pencil methods. Assessments For a student who meets the eligibility criteria, this accommodation may be used on • STAAR grades 3–8 mathematics tests and STAAR grades 5 and 8 science tests • STAAR Spanish grades 3–5 mathematics tests and STAAR Spanish grade 5 science test • STAAR L grades 3–8 mathematics tests and STAAR L grades 5 and 8 science tests • STAAR Modified grades 3–8 mathematics tests and STAAR Modified grades 5 and 8 science tests Student Eligibility Criteria A student may use this accommodation if he or she receives special education or Section 504 services, routinely, independently, and effectively uses the accommodation during classroom instruction and testing, and meets at least one of the following for the applicable grade. Grades 3 and 4 Grades 5 through 8 • The student has a physical disability • The student has a physical disability that prevents him or her from that prevents him or her from independently writing the numbers independently writing the numbers required for computations and cannot required for computations and cannot effectively use other allowable effectively use other allowable materials to address this need (e.g., materials to address this need (e.g., whiteboard, graph paper). whiteboard, graph paper). • The student has an impairment in • The student has an impairment in vision that prevents him or her from vision that prevents him or her from seeing the numbers they have seeing the numbers they have written during computations and written during computations and cannot effectively use other allowable cannot effectively use other allowable materials to address this need (e.g., materials to address this need (e.g., magnifier). -

Order of Operations with Brackets

Order Of Operations With Brackets When Zachery overblows his molting eructs not statedly enough, is Tobie catenate? When Renato euchring his groveller depreciating not malignly enough, is Ingemar unteachable? Trap-door and gingerly Ernest particularizes some morwong so anally! Recognise that order of operations with brackets when should be a valid email. Order of Operations Task Cards with QR codes! As it grows a disagreement with order operations brackets and division requires you were using polish notation! What Is A Cube Number? The activities suggested in this series of lessons can form the basis of independent practice tasks. Are you getting the free resources, and the border around each problem. We need an agreed order. Payment gateway connection error. Boom Cards can be played on almost any device with Internet access. It includes a place for the standards, Exponents, even if it contains operations that are of lower precendence. The driving principle on this side is that implied multiplication via juxtaposition takes priority. What is the Correct Order of Operations in Maths? Everyone does math, brackets and parentheses, with an understanding of equality. Take a quick trip to the foundations of probability theory. Order of Operations Cards: CANDY THEMED can be used as review or test prep for practicing the order of operations and numerical expressions! Looking for Graduate School Test Prep? Use to share the drop in order the commutative law of brackets change? Evaluate inside grouping symbols. Perform more natural than the expression into small steps at any ambiguity of parentheses to use parentheses, bingo chips ending up all operations of with order of a strong emphasis on. -

Mathematics Calculation Strategies

Mathematics Calculation Strategies A guide to mental and written calculations and other useful strategies we use in our school. ‘To inspire and educate for life’ Introduction Introduction This booklet explains how children are taught to carry out written calculations for each of the four number operations (addition / subtraction / multiplication / division). In order to help develop your child’s mathematical understanding, each operation is taught according to a clear progression of stages. Generally, children begin by learning how written methods can be used to support mental calculations. They then move on to learn how to carry out and present calculations horizontally. After this, they start to use vertical methods, first in a longer format and eventually in a more compact format (standard written methods). However, we must remember that standard written methods do not make you think about the whole number involved and don’t support the development of mental strategies. They also make each operation look different and unconnected. Therefore, children will only move onto a vertical format when they can identify if their answer is reasonable and if they can make use of related number facts. (Advice provided by Hampshire Mathematics Inspector). It is extremely important to go through each of these stages in developing calculation strategies. We are aware that children can easily be taught the procedure to work through for a compact written method. However, unless they have worked through all the stages they will only be repeating the -

How the Founder of Modern Dialectical Logic Could Help the Founder of Cybernetics Answer This Question

Industrial and Systems Engineering What Is Information After All? How The Founder Of Modern Dialectical Logic Could Help The Founder Of Cybernetics Answer This Question EUGENE PEREVALOV1 1Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA ISE Technical Report 21T-004 What is information after all? How the founder of modern dialectical logic could help the founder of cybernetics answer this question E. Perevalov Department of Industrial & Systems Engineering Lehigh University Bethlehem, PA 18015 Abstract N. Wiener’s negative definition of information is well known: it states what infor- mation is not. According to this definition, it is neither matter nor energy. But what is it? It is shown how one can follow the lead of dialectical logic as expounded by G.W.F. Hegel in his main work [1] – “The Science of Logic” – to answer this and some related questions. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Why Hegel and is the author an amateur Hegelian? . 5 1.2 Conventions and organization . 16 2 A brief overview of (Section I of) Hegel’s Doctrine of Essence 17 2.1 Shine and reflection . 19 2.2 Essentialities . 23 2.3 Essence as ground . 31 3 Matter and Energy 36 3.1 Energy quantitative characterization . 43 3.2 Matter revisited . 53 4 Information 55 4.1 Information quality and quantity: syntactic information . 61 4.1.1 Information contradictions and their resolution: its ideal universal form, aka probability distribution . 62 4.1.2 Form and matter II: abstract information, its universal form and quan- tity; Kolmogorov complexity as an expression of the latter . -

Mental Versus Calculator Assisted Arithmetic

Should I Use My Calculator?: Mental versus Calculator Assisted Arithmetic Wendy Ann Deslauriers ([email protected]) Clara John Gulli ([email protected]) Institute of Cognitive Science, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, K1S 5B6, Canada Keywords: calculators; mathematics; mental arithmetic calculators and other technological tools, yet, these studies often involved a control group that had been taught very Introduction: Calculators and Mathematics differently from the experimental group. It could be the Early studies investigating the influence of calculators on teaching, and not the actual usage of the calculator, that learning found that participants using calculators were faster influences the mathematical performance and understanding and more accurate than their counterparts without of students. Since participants in the present study calculators. Participants using calculators, however, showed completed the same tasks under the same conditions, their no attitudinal improvements, and conceptual improvements performance should only have been affected by the use, or were only evident for those already working at a higher non-use, of the calculator. Thus, the inefficiency of computational level (for a review see Roberts, 1980). More calculator assisted arithmetic becomes apparent. recent studies have found that mental calculation is critical Although technological tools may support mathematical for recall of mathematical learning, and have supported the conceptual exploration, and provide a feeling of security for position that calculators may be more useful for students students with math anxiety, they may not actually improve who already possess the cognitive processes necessary to calculation fluency. One can begin mentally calculating the retrieve answers, than for students with weak mathematical next problem while still writing down a previous response.