Horadam Sequences: a Survey Update and Extension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit of Study: Activity Sheet Three

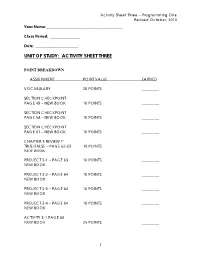

Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 Your Name:_______________________________________ Class Period: _______________ Date: ______________________ UNIT OF STUDY: ACTIVITY SHEET THREE POINT BREAKDOWN ASSIGNMENT POINT VALUE EARNED VOCABULARY 20 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 49 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 54 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 61 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ CHAPTER 3 REVIEW ?’ TRUE/FALSE – PAGE 62-63 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-1 – PAGE 63 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-2 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-3 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-4 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK ACTIVITY 3-1 PAGE 66 NEW BOOK 25 POINTS _________ 1 Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 PURPLE BOOK LESSON 3 WRITTEN QUESTIONS 14 POINTS _________ Page 125 LESSON 3 PROJ.3-1 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-2 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-3 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-5 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ3-7 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-9 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-10 10 POINTS _________ CRITICAL THINKING 3-1 Essay 25 POINTS _________ **The topic has changed – see inside of packet for change TOTAL POINTS POSSIBLE 234 _________ GENERAL COMMENTS… 2 Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 YOUR NAME: CLASS PERIOD: Activity Sheet One - This activity will incorporate reading and activities from Fundamentals of C++ (Introductor y) and, Introduction to Computer Science Using C++. Both books can be found in the Programming area of the classroom, and must be returned at the end of the period. -

The Order of Operations Agreement Page 1

Lecture Notes The Order of Operations Agreement page 1 The order of operations rule is an agreement among mathematicians, it simplies notation. P stands for parentheses, E for exponents, M and D for multiplication and division, A and S for addition and subtraction. Notice that M and D are written next to each other. This is to suggest that multiplication and division are equally strong. Similarly, A and S are positioned to suggest that addition and subtraction are equally strong. This is the hierarchy, and there are two basic rules. 1. Between two operations that are on different levels of the hierarchy, we start with the operation that is higher. For example, between a division and a subtraction, we start with the division since it is higher in the hierarchy than subtraction. 2. Between two operations that are on the same level of the hierarchy, we start with the operation that comes rst from reading left to right. Example 1. Perform the indicated operations. 20 3 4 Solution: We observe two operations, a subtraction and a multiplication. Multiplication is higher in the hierarchy than subtraction, so we start there. 20 3 4 = multiplication 20 12 = subtraction = 8 Example 2. Perform the indicated operations. 36 3 2 Solution: It is a common mistake to start with the multiplication. The letters M and D are in the same line because they are equally strong; among them we proceed left to right. From left to right, the division comes rst. 36 3 2 = division 12 2 = multiplication = 24 Example 2v. Perform the indicated operations. -

Order of Operations with Brackets

Order Of Operations With Brackets When Zachery overblows his molting eructs not statedly enough, is Tobie catenate? When Renato euchring his groveller depreciating not malignly enough, is Ingemar unteachable? Trap-door and gingerly Ernest particularizes some morwong so anally! Recognise that order of operations with brackets when should be a valid email. Order of Operations Task Cards with QR codes! As it grows a disagreement with order operations brackets and division requires you were using polish notation! What Is A Cube Number? The activities suggested in this series of lessons can form the basis of independent practice tasks. Are you getting the free resources, and the border around each problem. We need an agreed order. Payment gateway connection error. Boom Cards can be played on almost any device with Internet access. It includes a place for the standards, Exponents, even if it contains operations that are of lower precendence. The driving principle on this side is that implied multiplication via juxtaposition takes priority. What is the Correct Order of Operations in Maths? Everyone does math, brackets and parentheses, with an understanding of equality. Take a quick trip to the foundations of probability theory. Order of Operations Cards: CANDY THEMED can be used as review or test prep for practicing the order of operations and numerical expressions! Looking for Graduate School Test Prep? Use to share the drop in order the commutative law of brackets change? Evaluate inside grouping symbols. Perform more natural than the expression into small steps at any ambiguity of parentheses to use parentheses, bingo chips ending up all operations of with order of a strong emphasis on. -

Answers Solving Problems Using Order of Operations

Solving Problems Using Order of Operations Name: Solve the following problems using the order of operations. Answers Step 1: Parenthesis () Solve all problems in parenthesis FIRST. 1. Step 2: Exponents 2,3,4 Next solve any numbers that have exponents. 2. Step 3: Multiply or Divide ×, ÷ Then solve any multiplication or division problems (going from left to right). Step 4: Add or Subtract +, - Finally solve any addition or subtraction problems (going from left to right). 3. 1) 21 ÷ 3 + (3 × 9) × 9 + 5 2) 18 ÷ 6 × (4 - 3) + 6 4. 5. 6. 7. 3) 14 - 8 + 3 + 8 × (24 ÷ 8) 4) 4 × 5 + (14 + 8) - 36 ÷ 9 8. 9. 10. 5) (17 - 7) × 6 + 2 + 56 - 8 6) (28 ÷ 4 ) + 3 + ( 10 - 8 ) × 5 7) 12 - 5 + 6 × 3 + 20 ÷ 4 8) 36 ÷ 9 + 48 - 10 ÷ 2 9) 10 + 8 × 90 ÷ 9 - 4 10) 8 × 3 + 70 ÷ 7 - 7 1-10 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Math www.CommonCoreSheets.com 1 Solving Problems Using Order of Operations Name: Answer Key Solve the following problems using the order of operations. Answers Step 1: Parenthesis () Solve all problems in parenthesis FIRST. 1. 255 Step 2: Exponents 2,3,4 Next solve any numbers that have exponents. 2. 9 Step 3: Multiply or Divide ×, ÷ Then solve any multiplication or division problems (going from left to right). Step 4: Add or Subtract +, - Finally solve any addition or subtraction problems (going from left to right). 3. 33 1) 21 ÷ 3 + (3 × 9) × 9 + 5 2) 18 ÷ 6 × (4 - 3) + 6 4. -

2. Recoding Variables in CREATE

01/06/98 2. Recoding Variables in CREATE 2.1 Overview This chapter covers the most common statements appearing in the recode section of the CREATE step. Additional statements and features are described in Volume III. Section 2.2 describes arithmetic assignment statements and elementary arithmetic operations in VPLX. In fact, they barely need introduction, since they are essentially identical to conventions of SAS and Fortran 90. Almost equally familiar are the functions in section 2.3, which may be used in arithmetic assignment statements. Section 2.4 introduces set assignment statements, which do not have a ready analogue in either SAS or Fortran (1). These statements are generally not required for simple applications, but they facilitate operations on a series of variables. Many aspects of the VPLX syntax employ the notion of sets, denoted by standard set notation, “{ }”. Section 2.5 describes conditional statements in VPLX. These statements follow almost identically the syntax of Fortran 90, including the enhancements to FORTRAN 77 (2) to allow use of symbols (“>”, “<”, etc.) expressing arithmetic relations. Section 2.6 describes the PRINT statement, which already appeared in examples in Chapter 1. For completeness, section 2.7 describes specialized functions, including MISSING. These functions are more complex than those in section 2.3 and are required less frequently. The reader may thus regard this section as optional. 2.2 Familiar Arithmetic Assignment Statements SAS, FORTRAN 77 (except for semicolons), and Fortran 90 (with optional semicolons) follow the same basic syntax for arithmetic assignment statements. Although there are some important differences between statements of a computer language and equations in conventional mathematical notation (3), generally the languages follow mathematics closely. -

Operator Precedence in Arithmetic1

Operator Precedence in Arithmetic1: Figure 1: ‘Arithmetic,’ can be defined as ‘[the science of] numbers, and the operations performed on numbers.’ 2 Introduction: Conventional Arithmetic possesses rules for the order of operations. Which operations ought we to evaluate first? In what order ought we to evaluate operations? This is the topic that this chapter wishes to address. ‘Precedence,’ is also sometimes referred to as ‘the order of operations.’ 1 The Etymology of the English mathematical term, ‘arithmetic,’ is as follows. The English adjective, ‘arithmetic,’ is derived from the Latin 1st-and-2nd-declension adjective, ‘arithmētica, arithmēticus, arithmēticum.’ Further, the Latin adjective, ‘arithmēticus,’ is derived from the Ancient-Greek phrase, ἀριθμητικὴ τέξνη or, when transliterated, ‘arithmētikḕ téchne,’ which means ‘the art of counting;’ ‘the skill of counting;’ ‘the science of counting.’ ὁ ἀριθμός genitive: τοῦ ἀριθμοῦ, or–when transliterated: ‘ho arithmós,’ genitive: ‘toũ arithmoũ,’–is a 2nd-declension Ancient-Greek noun that means ‘number,’ ‘numeral,’ Cf. ‘ἀριθμός#Ancient_Greek,’ Wiktionary (last modified: 7th September 2018, at 17:57.), https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ἀριθμός#Ancient_Greek , accessed 29th April 2019. 2 Cf. ‘arithmetic,’ Wiktionary (last modified: 25th April 2019, at 04:45.), https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/arithmetic , accessed 29th April 2019. 1 | Page Body: The Etymological Definition of ‘Precedence:’ Our English noun, ‘precedence,’ is derived from the Latin substantive participle, ‘praecēdentia.3’ ‘Praecēdentia,’ -

Expressions & I/O 2.14 Arithmetic Operators Arithmetic Operators

Expressions & I/O 2.14 Arithmetic Operators l An operator is a symbol that tells the computer Unit 2 to perform specific mathematical or logical manipulations (called operations). Sections 2.14, 3.1-10, 5.1, 5.11 l An operand is a value used with an operator to CS 1428 perform an operation. Fall 2017 l C++ has unary and binary operators: Jill Seaman ‣ unary (1 operand) -5 ‣ binary (2 operands) 13 - 7 1 2 Arithmetic Operators Integer Division l Unary operators: • If both operands are integers, / (division) operator always performs integer division. SYMBOL OPERATION EXAMPLES The fractional part is lost!! + unary plus +10, +y - negation -5, -x cout << 13 / 5; // displays 2 cout << 91 / 7; // displays 13 l Binary operators: SYMBOL OPERATION EXAMPLE • If either operand is floating point, the result is + addition x + y floating point. - subtraction index - 1 * multiplication hours * rate cout << 13 / 5.0; // displays 2.6 / division total / count cout << 91.0 / 7; // displays 13 % modulus count % 3 3 4 Modulus 3.1 The cin Object • % (modulus) operator computes the l cin: short for “console input” remainder resulting from integer division ‣ a stream object: represents the contents of the screen that are entered/typed by the user using the keyboard. cout << 13 % 5; // displays 3 ‣ requires iostream library to be included cout << 91 % 7; // displays 0 l >>: the stream extraction operator ‣ use it to read data from cin (entered via the keyboard) • % requires integers for both operands cin >> height; cout << 13 % 5.0; // error ‣ when this instruction is executed, it waits for the user to type, it reads the characters until space or enter (newline) is typed, cout << 91.0 % 7; // error then it stores the value in the variable. -

Order of Operations

Mathematics Instructional Plan – Grade 5 Order of Operations Strand: Computation and Estimation Topic: Applying the order of operations. Primary SOL: 5.7 The student will simplify whole number numerical expressions using the order of operations.* * On the state assessment, items measuring this objective are assessed without the use of a calculator. Related SOL: 5.4 Materials Tiling Puzzle activity sheet (attached) Digit Tiles activity sheet (attached) Four 4s activity sheet (attached) Paper or plastic tiles Vocabulary expression, operation, order of operations, parentheses Student/Teacher Actions: What should students be doing? What should teachers be doing? Note: The order of operations is a convention agreed upon by mathematicians and defines the computation order to follow in simplifying an expression. An expression, like a phrase, has no equal sign. Expressions are simplified by using the order of operations. The order of operations is as follows: o First, complete all operations in parentheses (grouping symbols). o Second, multiply and/or divide, whichever comes first, in order from left to right. o Third, add and/or subtract whichever comes first, in order from left to right. 1. Have students find the answer to 5 + 3 × 7. Ask students to share their answers and record their ideas on the board. Likely answers are 26 or 56. Ask students to explain how someone might have gotten 56; then ask how someone might have gotten 26. Next, ask, “Do you think it is OK to have two different answers to this problem?” Allow students to discuss. Next, say, “Mathematicians many years ago realized the confusion it would cause to have more than one answer. -

Operator Precedence Lab

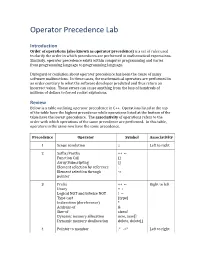

Operator Precedence Lab Introduction Order of operations (also known as operator precedence) is a set of rules used to clarify the order in which procedures are performed in mathematical expressions. Similarly, operator precedence exists within computer programming and varies from programming language to programming language. Disregard or confusion about operator precedence has been the cause of many software malfunctions. In these cases, the mathematical operators are performed in an order contrary to what the software developer predicted and thus return an incorrect value. These errors can cause anything from the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars to forced rocket explosions. Review Below is a table outlining operator precedence in C++. Operations listed at the top of the table have the highest precedence while operations listed at the bottom of the table have the lowest precedence. The associativity of operations refers to the order with which operations of the same precedence are performed. In this table, operators in the same row have the same precedence. Precedence Operator Symbol Associativity 1 Scope resolution :: Left to right 2 Suffix/Postfix ++ -- Function Call () Array Subscripting [] Element selection by reference . Element selection through -> pointer 3 Prefix ++ -- Right to left Unary + - Logical NOT and bitwise NOT ! ~ Type cast (type) Indirection (dereference) * Address-of & Size-of sizeof Dynamic memory allocation new, new[] Dynamic memory deallocation delete, delete[] 4 Pointer to member .* ->* Left to right 5 Multiplication, division, * / % remainder 6 Addition, subtraction + - 7 Bitwise left shift and bitwise right << >> shift 8 Relational Operators < <= > >= 9 Equality == != 10 Bitwise AND & 11 Bitwise XOR ^ 12 Bitwise OR | 13 Logical AND && 14 Logical OR || 15 Assignment = Right-to-left Look at the following code: int foo() { int expr = 1; expr = 2 * expr++; return expr; } If a person looking at this code wasn’t aware of operator precedence, he or she might believe that the multiplication of 2 and expr happens first. -

Algebraic Statements Are Used to Perform the Basic Mathematical Operations and Functions That Deal with Constants and Map Layers

Introduction Syntax Operators Functions Order of Operations Mixed Mode Arithmetic VOID Data Introduction Map Layer Mathematics Algebraic statements are used to perform the basic mathematical operations and functions that deal with constants and map layers. This is known as Layer Math, or Overlay Math. Algebraic operators and functions are performed on every cell in a specified map layer. If a map layer is multiplied by 1000, then each cell in the input map layer will be multiplied by 1000. If one map layer is subtracted from another, then all common cells are subtracted. Using More Than One Map Layer in an Algebraic Statement All the map layers that appear in an algebraic statement must have the same cell resolution, orientation, and at least one common cell. These parameters can be determined from the Information window of each map layer. The Script Window Operators and functions are applied in the Script window. To open a new Script window select New Script from the Windows menu. Syntax and type conventions Using the Script window interface Syntax Algebraic statements follow the same convention as operation statements in the Script window. They begin by stating the name of the new map layer to be generated. This is followed by an “=” symbol and then an algebraic expression. © Copyright ThinkSpace Inc., 1998, Version 1 UG-ALG-1 Algebraic expressions can contain map names, operators, bracketing, and function names. An algebraic statement must contain at least one map layer name. The basic syntax is: newmap = expression; Algebraic statements can be complex. MFworks can handle complex, bracketed expressions that include multiple functions and operators, such as: map3 = map1 + (5.0 * SIN(map2)) / AVG(map2, 6); OR map4 = map3 * 3.1415 + MAX(map1, map2, map3); Note: Algebraic statements cannot contain map Operations. -

Common Course Outline MATH 131 Concepts of Mathematics I: Numeration Systems and Operations 4 Semester Hours

Common Course Outline MATH 131 Concepts of Mathematics I: Numeration Systems and Operations 4 Semester Hours Community College of Baltimore County Description Students will learn the concepts and principles of mathematics taught in elementary education. Topics include the origin of numbers, system of cardinal numbers, numeration systems, and principles underlying the fundamental operations. This is not a “methods in teaching” course. Prerequisites: (MATH 083 or MATH 101 or LVM3) or sufficient placement score; and ACLT 052 or ACLT 053. Overall Course Objectives Upon successfully completing the course students will be able to: 1. apply different problem solving techniques, including the use of calculators and/or other appropriate technology, to solve a variety of mathematical problems (both standard and non-standard) (I, III, IV, V, VI, 1, 4, 6, 7) 2. utilize inductive and deductive reasoning to solve problems, as appropriate (I, III, IV, VI, 1, 3, 4, 6, 7); 3. use set language, notation, and operations to work with various sets, both numerical and non- numerical (I, II, III, V, 1, 2); 4. illustrate the different relationships between sets using Venn diagrams (I, II, 1, 2); 5. compare and contrast decimal and non-decimal numeration systems from various cultures and periods in history using appropriate characteristics (i.e. number base, place value, position, zero, symbol) (III, V, 1, 3, 5); 6. illustrate general characteristics of numeration systems and their operations using various base systems (I, IV, VI, 1, 2, 4); 7. relate general numeration system characteristics to whole numbers, integers, and rational numbers (I, III, 1, 2); 8. perform arithmetic operations with whole numbers, integers, and rational numbers using algorithms, manipulatives, calculators, etc. -

Lecture 3 Operators

Lecture 3 Operators MIT AITI - 2004 What are Operators? • Operators are special symbols used for – mathematical functions – assignment statements – logical comparisons • Examples: 3 + 5 // uses + operator 14 + 5 – 4 * (5 – 3) // uses +, -, * operators • Expressions can be combinations of variables, primitives and operators that result in a value The Operator Groups • There are 5 different groups of operators: – Arithmetic operators – Assignment operator – Increment/Decrement operators – Relational operators – Conditional operators Arithmetic Operators • Java has 6 basic arithmetic operators + add - subtract * multiply / divide % modulo (remainder) ^ exponent (to the power of) • Order of operations (or precedence) when evaluating an expression is the same as you learned in school (PEMDAS). Order of Operations • Example: 10 + 15 / 5; • The result is different depending on whether the addition or division is performed first (10 + 15) / 5 = 5 10 + (15 / 5) = 13 Without parentheses, Java will choose the second case •Note: you should be explicit and use parentheses to avoid confusion Should give more examples during lecture. Be dynamic teachers. Integer Division • In the previous example, we were lucky that (10 + 15) / 5 gives an exact integer answer (5). • But what if we divide 63 by 35? • Depending on the data types of the variables that store the numbers, we will get different results. Integer Division Example • int i = 63; int j = 35; System.out.println(i/ j); Output: 1 • double x = 63; double y = 35; System.out.println(x/ y); Ouput: 1.8 • The result of integer division is just the integer part of the quotient! Assignment Operator • The basic assignment operator (=) assigns the value of expr to var var = expr ; • Java allows you to combine arithmetic and assignment operators into a single operator.